A Mahanian cult of the offensive permeates today’s U.S. Navy.1 This is—mostly—a good thing; the Navy could not be successful in the struggle for sea control without having offensive spirit. Yet experience shows that too much focus on offense at the expense of defensive war-fighting is fraught with great danger. At present, the Navy does not pay the required attention to critical warfare areas such as sea denial, defense and protection of maritime trade, mine warfare (especially mine countermeasures), support of land forces, or even, until relatively recently, antisubmarine warfare (ASW). The Navy should heed lessons from its own history, as well as the experience of other navies, to see the results of a single-minded focus on either offense or defense.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), for example, neglected defensive aspects of naval warfare—in particular, the defense and protection of maritime trade and antisubmarine defense. The IJN was a formidable but tactical force. It was led and trained excellently, especially in night fighting, and had superb gunnery and torpedo tactics. In 17 major surface engagements with Allied forces in 1941–42, the IJN won 10, lost 4, and had 3 draws.2 Yet its tactical brilliance was insufficient to overcome its lack of a sound strategy and ignorance of operational art. This is the problem facing the U.S. Navy today.

The roots of the Navy’s singular focus on offense go back to Alfred Thayer Mahan.3 Writing at the end of the 19th century, Mahan emphasized the need to take the offensive strategically and tactically, and his teachings were accepted by almost all leaders in major navies.4 He insisted that by giving up the offensive, a navy gives up its “proper sphere.”5 He wrote that employing a navy in passive defense is faulty because “the distinguishing feature of naval force is mobility, while that of passive defense is immobility.”6

Mahan should not be blamed, however, for the uncritical acceptance of his ideas by generations of U.S. naval officers. His ideas, like those of other classical naval thinkers, should be continually reevaluated and modified, changed, or even discarded if found wanting.

Sea Control versus Sea Denial

The Navy’s understanding of sea control is unsatisfactory, at least judging by current doctrine. Naval Doctrine Publication 1 (NDP-1) Naval Warfare (2010), the Navy’s foundational operational document, does not clearly define sea control. Neither does it explain the principle methods for obtaining, maintaining, and exercising sea control, saying only that it requires:

control of the surface, subsurface, and airspace and relies upon naval forces’ maintaining superior capabilities and capacities in all sea-control operations. It is established through naval, joint or combined operations designed to secure the use of ocean and littoral areas by one’s own forces and to prevent their use by the enemy.7

NDP-1 defines “sea-control operations” as:

The employment of naval forces, supported by land, air, and other forces as appropriate, in order to achieve military objectives in vital sea areas. Such operations include destruction of enemy naval forces, suppression of enemy sea commerce, protection of vital sea lanes, and establishment of local superiority in areas of naval operations.8

NDP-1’s authors mixed tactics and operational art by stating that “sea-control operations involve locating and dealing with a variety of contacts. Imposing sea control close inshore may require the control of key geographic areas such as straits or peninsulas through seizure and/or defense of key terrain ashore.”9 The authors conflate actions aimed at obtaining sea control with ones that are part of exercising it.

The Navy apparently has no conception it could be forced to go strategically on defense either at the beginning or in the midst of a major regional war. But no matter how strong, any blue-water navy might find itself in such a position. In other words, it might need to fight at least temporarily for sea denial rather than control. NDP-1 neither defines nor discusses sea denial, but it can be described generically as one’s ability to deny partially or completely the enemy’s use of the sea for military and commercial purposes. The Navy’s lack of thinking on sea denial means it is doctrinally, materially, and psychologically unprepared to dispute control of the sea.

An offensive minded navy can be strategically on the defensive while acting offensively operationally and tactically. For a stronger side, a strategically defensive posture can be temporary, not the permanent condition it is for a weaker side. And the situation can vary even within different parts of the same theater. The first years of World War II in the Pacific offer examples of each.

After Pearl Harbor, the Navy was strategically on the defensive, but operationally and tactically it acted offensively. U.S. fast carrier forces conducted raids against Japanese strongholds in the central and southwestern Pacific, while submarines initiated unrestricted warfare against Japanese merchant shipping. Decisive victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942 created conditions for a shift to the strategic offensive. The U.S. landing on Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942 was the initial major naval/joint operation in what later evolved to the Solomon Islands Campaign. It took some 17 months (August 1942–December 1943) of hard fighting on land, at sea, and in the air before the Allies captured the Solomons. Afterward they stayed strategically on the offensive until the final victory over Japan in August 1945.

The stronger side at sea also may be strategically on offense in one theater but on defense elsewhere, especially if it selected faulty strategic objectives and distributed its forces poorly, as Britain did in the War of American Independence (1775–83). At the beginning of the war, the Royal Navy was numerically stronger than either the French or Spanish navies, with an even more favorable advantage off North America and in the West Indies. However, concentrating its force for an offensive in the West Indies reduced its strength in home waters.10 The situation worsened for Britain when Spain joined France against Britain by signing the secret Treaty of Aranjuez on 12 April 1779.11 The Royal Navy almost immediately became the weaker side in European waters. A comparably dangerous situation might confront the U.S. Navy should the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Russian Federation become allies or coalition partners—or merely cooperate—in case of a war in the western Pacific.

The Best Defense is also a Good Offense

In the modern era, the U.S. Navy has paid little attention to critical defensive warfare areas, such as defense and protection of merchant shipping, mine warfare, and support of troops ashore.

Convoys

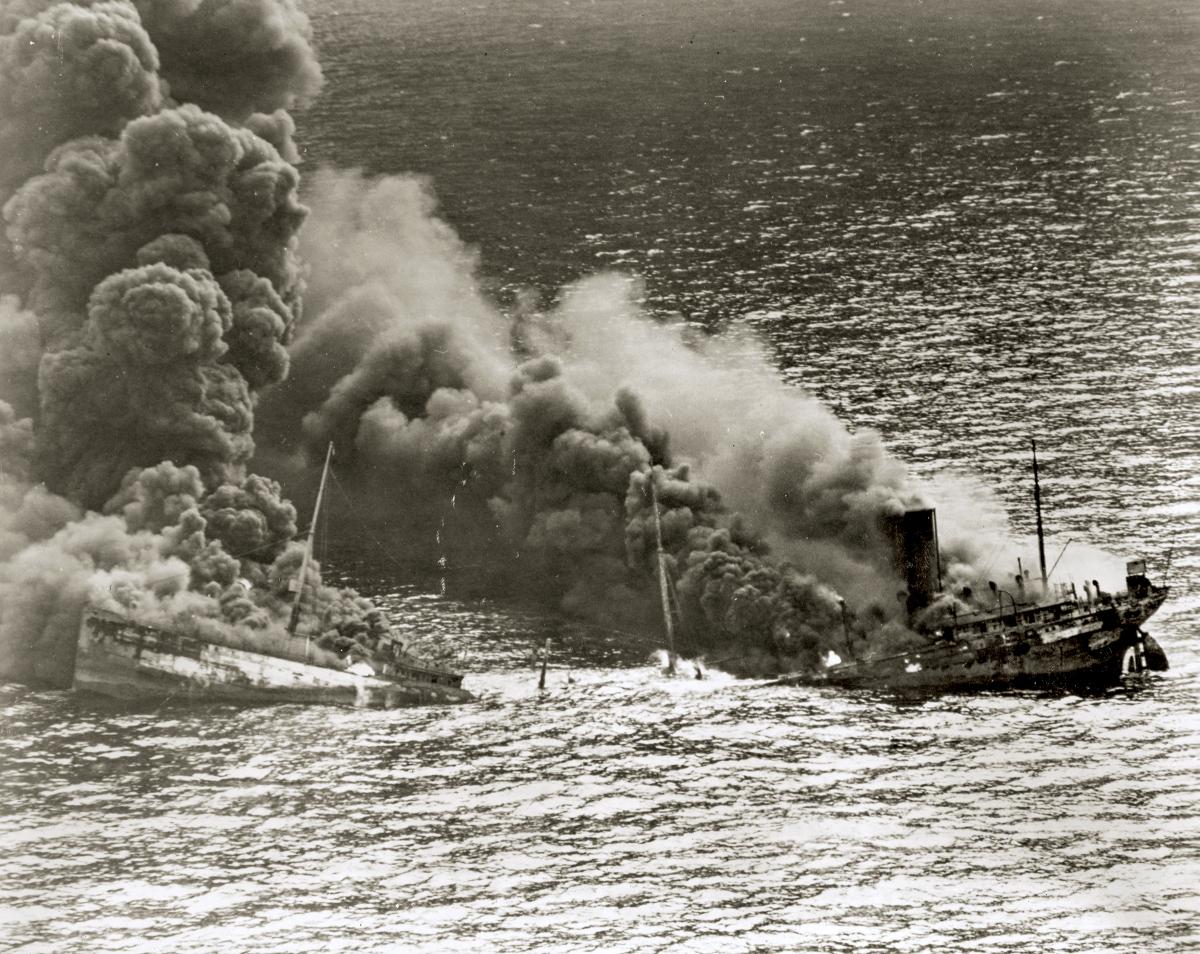

Defense and protection of maritime trade should be organized and practiced in peacetime. In a high-intensity conventional war at sea, failure to ensure the safety of one’s own maritime trade is bound to have adverse and often fatal consequences on a war’s outcome, as the Second World War experience of the IJN illustrates. It is misleading even to label the task as “defensive” because it is one of any navy’s core missions. The current U.S. maritime strategy asserts, “We will not permit an adversary to disrupt the global supply chain by attempting to block vital sea-lines of communications and commerce.”12 Protecting U.S. maritime trade cannot be accomplished without close cooperation between the Navy and other services, other government organizations, the private maritime industry, the scientific community, and universities.

Prior to both world wars, the overemphasis on decisive fleet-versus-fleet actions led to neglect of this “defensive” mission, which resulted in unacceptable losses to merchant shipping at the outset of each.13 Strategists and thinkers paid too much attention to Mahan’s arguments in favor of offensive action but did not heed his remarks on the importance of merchant shipping for a sea power. Mahan wrote that “the necessity of a navy, in the restricted sense of the words, springs, therefore, from the existence of a peaceful shipping, and disappears with it.”14 His strong support for convoying as the most effective method for defense and protection of shipping was virtually ignored.15

The Navy focused almost exclusively on protecting its own naval supply ships—the logistical “train”—while giving the safety of commercial maritime shipping short shrift, and the submarine threat to merchant ships was seriously underestimated. Despite the Navy’s role in defeating German U-boats in World War I, by 1939 the lessons surrounding maritime trade were almost forgotten.16

Even though the U.S. Navy functioned as a de facto ally of the Royal Navy in defense of convoys in the northern Atlantic in 1940–41, it was woefully unprepared to provide effective shipping defense after Nazi Germany formally declared war on the United States in December 1941. It was not until May 1942, nearly six months after the United States entered the war, that the U.S. Navy introduced its own convoys. By then, the Germans had sunk 87 ships of 514,000 gross register tons off the East Coast.17 It took until September 1942 to get the complex but highly effective interlocking convoy system into place.18

In October 2018, the maritime administrator, retired Rear Admiral Mark Buzby, reported that the Navy has told his agency the service will not be able to escort Military Sealift Command (MSC) ships during a major war. They should “go fast, stay quiet.”19 Yet MSC will be expected to move some 90 percent of Marine Corps and Army gear to sustain operations ashore. The Navy apparently has forgotten that the primary purpose of obtaining control of the sea is to secure uninterrupted flow of merchant and military shipping.

The problem is not merely one of planning; the Navy does not possess the tools to perform this critical task. There is no doctrine—not a single document—that explains the operational employment of naval/joint forces in defense of maritime trade. And the Navy lacks frigates and multipurpose corvettes for escort duties. The littoral combat ship will not have the flexibility originally envisioned, and solutions such as the FFG(X) program are years from entering the fleet.

Mines

Mine warfare—especially mine countermeasures—is another area to which the Navy has paid scant attention. Mine warfare has been regarded as a task that virtually any line officer can perform when the time comes, not generally appreciated as the kind of warfare that requires much training, experience, or research. Consequently, mines have been disregarded as a serious threat to sea control.20

The Navy considers mine warfare “defensive” and therefore somehow less important than other fundamental areas of war at sea. But at sea there is no such thing as purely defensive warfare. Before World War II, a lack of preparation for offensive use of mines against merchant ships adversely affected Navy efforts to inflict damage on Japanese shipping. Prewar, only a single Naval Ordnance Laboratory physicist worked on mines.21 This was the main reason large-scale mining of Japanese-controlled ports did not start in earnest until well into 1943.

After the war, the Navy resumed neglecting mine warfare, and most minesweepers were decommissioned. As a result, the Navy was unprepared when mines reemerged during the Korean War. Lack of adequate mine countermeasure capabilities delayed a landing at Wŏnsan in October 1950. Since 1945, the U.S. Navy has had 14 ships damaged by mines, while only 5 ships were damaged by other hostile actions.22

One Team, One Fight

The Navy has provided effective support to the Army in offensive and defensive operations throughout U.S. history. Yet, NDP-1 and other doctrinal publications do not discuss in any detail Navy tasks in support of troops ashore. Nor has the Navy paid much attention to coastal defense, another result of uncritical acceptance of Mahan.

For Mahan, naval forces lock up their offensive strength in a defensive effort when they defend a port or a coastal base. He believed such employment injurious to the morale and skill of seamen, when the method of a fleet should be to take the offensive. By giving up the offensive, Mahan believed, the Navy gives up its proper sphere.23

The combined-arms approach of the Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations documents developed recently by the Navy and Marine Corps are good first steps toward improvement in this area, but both services must develop the details that will make this an operational area with doctrinal teeth.

Don’t Ignore ‘Defense’

The first and most important objective for the Navy in any major war at sea would be to quickly obtain and then maintain control of the sea in a given part of a maritime theater—that is, to employ its forces offensively. Sea control is, after all, the key prerequisite for ensuring the safety of military and commercial shipping, conducting amphibious landings, destroying enemy coastal installations, providing support to friendly forces on land, and protecting territory from seaborne invasion. Hence, Carl von Clausewitz’s dictum that “attack [is] the weaker and defense the stronger form of war” does not apply to naval warfare.24 The reason is navies operate in a very different physical environment than armies.

The U.S. Navy must remain an offensive force imbued with offensive spirit; otherwise it would be ineffective in defending national interests at sea. Yet experience teaches that the Navy has neglected—and continues to neglect—less glamorous but critical defensive warfare areas, at great peril to the Navy and the nation. The Navy must find a proper balance between its purely offensive capabilities and other warfare areas.

This is a problem not only of battle force composition but also the mind-set of naval officers, and shifting resources cannot solve it. The Navy’s culture must change. The service must develop comprehensive naval theory, appropriate doctrine, and training methods to reshape the force. The fate of the former IJN should serve as a stern warning to the U.S. Navy not to neglect any aspect of warfare because it is “defensive.” Advanced technology is insufficient to win a war against an enemy brilliant in both tactics and operational art.

1. Michael C. Grubb, Protection of Shipping: A Forgotten Mission with Many Challenges (Newport, RI: Naval War College, 10 October 2006), 6.

2. David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 500–501.

3. Cited in Philip A. Crowl, “Alfred Thayer Mahan: The Naval Historian,” in Peter Paret, ed., Makers of Modern Strategy. From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), 458–59.

4. Cited in Grubb, Protection of Shipping, 4.

5. RADM Alfred T. Mahan, USN (Ret.), Naval Strategy: Compared and Contrasted with the Principles and Practice of Military Operations on Land (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1911), 153.

6. Mahan, Naval Strategy, 132.

7. Naval Doctrine Publication 1 (NDP-1), Naval Warfare (March 2010), 28.

8. NDP-1, 27–28.

9. NDP-1, 28.

10. Julian S. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1918), 189.

11. John B. Hattendorf, “The Idea of a ‘Fleet in Being’ on Historical Perspective,” Naval War College Review 67, no. 1 (Winter 2014): 49.

12. A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, October 2007), 10.

13. Grubb, Protection of Shipping, 2.

14. CAPT Alfred Thayer Mahan, USN, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 5th ed., 1894), 26.

15. Alfred R. Bowling, The Negative Influence of Mahan on the Protection of Shipping in Wartime: The Convoy Controversy in the Twentieth Century (Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International, unpubl. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maine, 1980), 2.

16. David MacGregor, “The Use, Misuse, and Non-Use of History: The Royal Navy and the Operational Lessons of the First World War,” The Journal of Military History 56, no. 4 (October 1992): 603.

17. Jürgen Rohwer, “Der U-Boot-Krieg: Die Schlacht im Atlantik (1939–1945),” in E. B. Potter and Chester W. Nimitz, Seemacht von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (Herrsching: Manfred Pawlak Verlag, 1986), 535.

18. Eliot A. Cohen and John Gooch, Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War, 1st ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 67.

19. David B. Larter, “You’re on Your Own: U.S. Sealift Can’t Count on Navy Escorts in the Next Big War,” Defense News, 10 October 2010.

20. Malcolm W. Cagle and Frank A. Manson, The Sea War in Korea, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1957), 126–27.

21. Arnold S. Lott, Most Dangerous Sea. A History of Mine Warfare and an Account of U.S. Navy Mine Warfare Operations in World War II and Korea (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1st ed., 1959), cited in Otto Lippa, Der Minenkrieg im Pazifik 1941–1945 (Hamburg: Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr, January 1963), 6.

22. Sandra I. Erwin, “Shallow-Water Mines Remain ‘Achilles’ Heel’ of U.S. Navy,” National Defense (January 2002), 16.

23. Mahan, Naval Strategy, 153.

24. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret ed. and trans. (New York/London/Toronto: Everyman’s Library, Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 634–35.