Imagine a great power war erupts in the next 30 years. Congressional mandate and the iron law of defense procurement suggest the U.S. Navy would enter the conflict with between 8 and 12 nuclear-powered aircraft carriers (CVNs). The Navy plans to construct a CVN every five years until 2028, accelerated to every four years from 2028 to 2048. If carrier strike groups (CSGs) built around Nimitz-class carriers in the second halves of their lives, post refueling and overhaul, and their Ford-class successors went to battle relying on current capabilities and established doctrine, would they prevail? Much ink has been spilled speculating about the answer, and rightly so. A great deal of U.S. blood and treasure is at stake.

Carriers cannot ignore emerging technologies. Advances in the speed, range, coordination, and accuracy of antiship weapons could turn them into modern equivalents of dreadnought battleships: invincible one day, seemingly obsolete the next. However, neither champions nor detractors of continued investment in CVNs have tackled a question that will matter whether the CVNs retain primacy or fade into a support role: Assuming carriers remain in the fleet, what improvements would give them the best chance for victory?

The Navy needs a platform dedicated to accomplishing for air warfare what the USS Zumwalt (DDG-1000) and the Surface Development Squadron aim to do for surface warfare.1 The planned decommissioning of the USS Nimitz (CVN-68) in 2025 presents an opportunity. Drawing on its past, the Navy should designate the Nimitz as CVN(X) and overhaul her into an experimental carrier.

The Strategic Challenge

As stressed in Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson’s Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority Version 2.0, the Navy must prepare for conflict with near-peer competitors in contested environments. There is reason to question how the United States would fare.

While miscalculation or accident may provide the spark, great power wars ignite when an aggressor believes it can win. Germany did not invade Poland nor did Japan strike Pearl Harbor without believing they could carve a path to victory. Near-peer competitors have invested in countering U.S. military advantages. Should advancements in “carrier killer” missiles, directed-energy weapons, autonomous vehicle swarms, and artificial intelligence continue as predicted, an adversary might be emboldened to cast the dice, crossing the Rubicon from competition to war.

States in crisis use the tools at hand, and the CVN-led CSG is the United States’ tool of choice.2 But using CVNs in a great power conflict would pose a Hobson’s choice:

- Deploy them to a contested area without appreciating the adversary’s capabilities and risk the same fate as the doomed HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales—belated proof that a class of ships has lost its ability to command the seas3

- Keep the CVNs out of the fight, depriving land-based and surface combatants of carrier air support and forcing U.S. vessels to operate in a different organizational construct than the CSG, from which the Navy derives so much fighting doctrine

In reality, there may be no choice. Despite the promise of a distributed force of F-35Bs, the Navy does not yet have a true alternative to CVN airpower. Even if it did, keeping the CVNs bottled up would run counter to U.S. naval tradition stretching from John Paul Jones to Cliff Sprague and the outgunned heroes of Taffy 3. The Navy prizes seizing the initiative and engaging the enemy with whatever ships can fight, even facing grim odds.

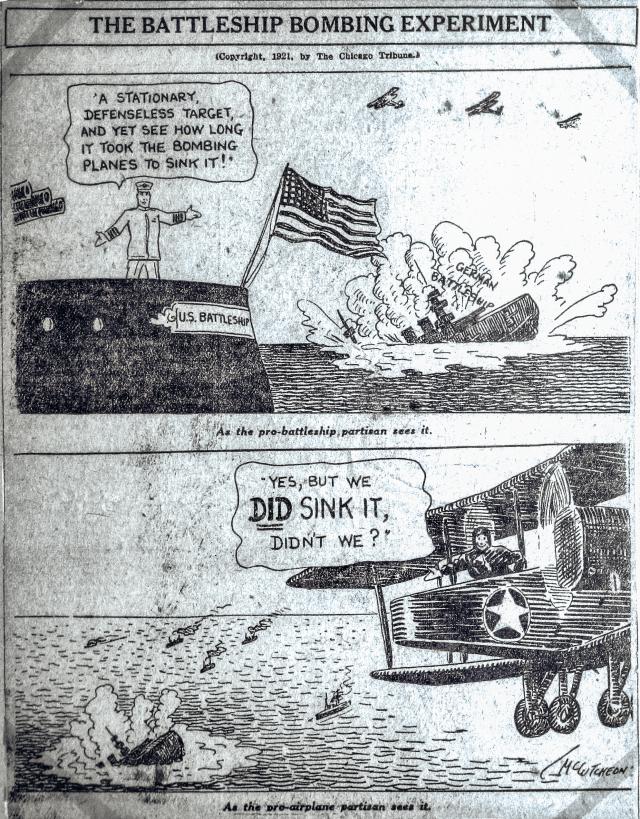

What role CVNs will play in the next conflict cuts to the core of a debate rooted in Navy intraservice rivalry. Looking at the battleship, those who believe the carrier age is over assume history will repeat itself. They see parallels to 1921, when airpower trials led by General Billy Mitchell sank the captured SMS Ostfriesland, demonstrating battleships’ vulnerability to air attack decades before the Combined Japanese Fleet exploited this weakness at Pearl Harbor. It may be better, critics conclude, to transition now from a carrier-led fleet to, for example, greater reliance on submarines, rather than wait for an adversary to exploit the carriers’ vulnerabilities in combat.

However, the “carriers are modern battleships” narrative obscures two points. First, if the Navy had acknowledged the battleships’ weaknesses earlier, there is no reason they could not have been better equipped—in terms of defensive capabilities, training, and force distribution—to better handle the danger posed by air attack. The decline narrative ignores that modified battleships continued to serve in key support roles even after carriers supplanted them as the primary striking arm of the U.S. Navy. Should there prove to be truth in predictions of the decline of the carrier, it would be prudent to experiment now with how those remaining in the fleet can enhance their survivability and contribute in a support role.

Second, reports of the demise of the carrier may be exaggerated. Projection of air power across the oceans will remain a priority, even if it becomes more dangerous and carrier aircraft must develop better range. Advances in missile defense may negate concerns over the CVNs’ survivability. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which have proven their utility in land-based combat, must have somewhere to be armed, launched, and recovered at sea, and more experimentation is needed to determine how they are best used in the maritime domain. There may yet be a role for large carriers.

So before either sending CVNs on a charge of the Light Brigadeor preemptively resigning them to obsolescence, the Navy should start thinking about how it might modify existing CVNs for future conflict. In doing so, it can look to the past.

The Birth of the Carrier Navy

Innovating for the future on hulls from the past is in the DNA of the carrier navy. The USS Lexington (CV-2) and her sister ship, the USS Saratoga (CV-3), became the foundation of the early U.S. carrier fleet by accident. Designed as battlecruisers, they were converted mid-construction because of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922.

Intended to prevent a naval arms race, the treaty locked in the ratio of capital ships and tonnage among the World War I victors.4 In the United States at the time, the Naval Act of 1916 called for building an additional 16 capital ships, including six heavy battlecruisers.5 Eleven of the 16 planned ships were canceled, but a compromise was struck to soften the blow to shipbuilders. Because carriers were only an ancillary concern under the Washington treaty, Navy planners redesignated the unfinished hulls of the Lexington and Saratoga from battlecruisers (CCs) to aircraft carriers (CVs) and gave them flight decks.6

Once the carriers entered the fleet in 1928, the Navy found a use for these new, if still underappreciated, assets. The Lexington and Saratoga’s participation in Fleet Problem exercises from 1929 through 1941 provided crucial lessons on the limits and potential of sea-based airpower. In June 1930, as part of Fleet Problem XII, their failure to protect the west coast of Panama from a hypothetical invasion showed the danger to carriers of coming in range of surface ships.

During 1932’s Grand Joint Exercise No. 4 and again before 1933’s Fleet Problem XIV, the carriers were tasked to launch surprise air attacks on Pearl Harbor, showing the offensive potential of carriers that could launch against an unsuspecting target.

In Fleet Problem XIII, in a simulated attack, the Lexington sank the Saratoga, catching her with her planes on deck.7 Ten years later, Japanese Admiral Chuichi Nagumo learned this Achilles heel of carrier dueling when U.S. planes caught his reserve planes rearming at Midway.

Having the two carriers operational in the interwar years—available for experimentation and exercises—primed U.S. forces for carrier-led combat. Equally important was the impact on future leaders. For nearly a decade, before the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Yorktown (CV-5) commissioned in 1936 and 1937, a generation of naval aviators learned how to operate at sea on the Lexington and Saratoga.8 Future flag officers and squadron commanders began experimenting under real-life conditions with how to employ sea-based airpower, building on lessons learned from the introduction of air assets in Naval War College war games of the 1920s.9

Cutting his teeth during this interwar period was John Thach, who spent two years on board battleships before transitioning to naval aviation in 1930. A decade later, after commanding a squadron embarked on board the Saratoga, the future admiral’s “Thach Weave” tactic gave U.S. pilots an edge against the technically superior Japanese Zero.10

Seeing the shortcomings of the new carriers proved equally beneficial. The need for a larger and heavier ship to carry a bigger air group, the benefits of a longer and wider flight deck, more efficiently arranged machinery, greater armor, and an improved elevator system—all incorporated in the design of the Yorktown class and later the Wasp and Essex classes—came from lessons learned on the converted battlecruisers.11

The Rebirth of the Battleship

While the Lexington and Saratoga illustrate how the Navy might benefit from experimenting early, the analogy to CVNs is imperfect. Converting unfinished hulls is qualitatively different from overhauling an aging ship. A better analogy may be the improved battleships that served throughout World War II and beyond, operating in a support role.

During the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands in 1942, the USS South Dakota (BB-57), modified with additional antiaircraft emplacements, brought down numerous Japanese aircraft, protecting the Enterprise battle group.12 Battleships also served in Korea, Vietnam, and the Persian Gulf. While they relied on carrier air cover, the battleships nonetheless contributed to the fight. During the USS Missouri’s (BB-63) distinguished service in Korea, for example, her concentrated gunfire protected First Marine Division’s evacuation from Hungnam in the December 1950 “Christmas Miracle.”

The Cold War reactivation of the Iowa class is perhaps the best illustration how the Navy could benefit from reimagining the CVNs’ role and investing in refurbishment. Then, as now, policymakers grappled with how to grow the fleet. In 1978, a lunchtime conversation between Charles Myers Jr., a former aviator, and an old Navy pal, Charles Haskell, breathed new life into the decommissioned Iowa-class battleships. They lamented that in Vietnam, reliance on aviation unnecessarily risked pilots on missions that surface ship batteries could have accomplished. This led Myers to produce a 50-page report entitled “Reactivation of Iowa-Class Battleships: A Basis for Advocacy” and circulate it to members of Congress.13

A version of Myers’ proposal appeared in the November 1979 Proceedings.14 He suggested bringing the Iowa-class battleships out of mothballs and giving them modern armaments. It was a bold vision. In addition to bringing the battleships’ big guns back online, he called for batteries of antiship missiles, land-attack cruise missiles, 155-millimeter howitzers, and four close-in weapon systems for self-defense to improve their lethality and ability to operate independently. As envisioned, the ships would have carried a combined loadout of 320 Tomahawks, antisubmarine rockets, and surface-to-air missiles. Myers also suggested installing aircraft elevators and an aft flight deck to accommodate up to 12 Harriers. Dubbing them “Interdiction Assault Ships,” he proposed that the refurbished battleships focus on countering the Soviet Union’s new Kirov-class nuclear battlecruisers and supporting Marine Corps air assaults.

The plan garnered criticism. Senator Dale Bumpers of Arkansas compared it to reactivating horse-based cavalry. President Jimmy Carter wrote Senate Armed Services Committee chairman John Stennis that he could not support spending “hundreds of millions of dollars to resurrect 1940’s technology.”15 However, the proposal caught the eye of John Lehman, an advisor to President-elect Ronald Reagan and future Secretary of the Navy. Of interest to Lehman was Myers’ proposal to equip the ships with a large complement of long-range Tomahawks, which would improve the United States’ Cold War strategic position. After President Reagan assumed office in 1981 and prioritized defense spending, Congress appropriated funds to reactivate the USS New Jersey (BB-62) and USS Iowa (BB-61). Over the following eight years, the Navy recommissioned all four of the Iowa-class battleships.

Cost and expediency prevented the Navy from fully embracing Myers’ vision for an Interdiction Assault Ship. Nevertheless, even the scaled-down refurbishments had an impact. The Missouri and USS Wisconsin (BB-64) contributed to Operation Desert Storm, striking Iraqi land targets with their 16-inch guns, clearing minefields, and using Pioneer unmanned aircraft for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) over Iraq and Kuwait. When war planners needed a diversion to convince Iraqi forces that an amphibious assault on Kuwait was imminent, distracting from the land assault, they turned to the battleships. An intensive shore bombardment did the trick.16

The battleships eventually were decommissioned, succumbing to the same concerns that will plague efforts to overhaul CVNs: high costs and large numbers of personnel required to man, equip, and operate the vessels. Yet they still are an example where the Navy innovatively updated old hulls with new technology, adding ships when the national strategy depended on growing the fleet.

CVN(X)

If improved technology and tactics create innovative uses for CVNs, in either a primary or a support role, the challenge will be to operationalize them before conflict. The interwar and late–Cold War periods show that experimentation can pay dividends. The alternative—learning how to retrofit CVNs during the early stages of a conflict—would keep the carriers out of the fight when the Navy might most need them. The Navy should begin experimenting now with how to adapt its carrier force for future naval combat, starting with the Nimitz.

Rather than decommissioning the Nimitz in 2025 and starting the costly process of scrapping her—or, more likely, succumbing to inevitable pressure to extend her operational life—the Navy should seek the support of Congress to overhaul the Nimitz into CVN(X) and use the intervening years to plan how to best integrate emerging technologies. CVN(X) could remain in use for as many service years as her reactors will allow.

Drawing a lesson from the employment of the Lexington and Saratoga in Fleet Problems, CVN(X)’s full-time mission should be to experiment in real-world conditions without being subject to routine tasking or a deployment cycle. Efforts to experiment with future naval airpower on carriers tasked primarily with supporting the national defense mission have been piecemeal, far less than what is required to maintain an edge over near-peer competitors, and incorporating changes into the Ford class without testing under real-world conditions has proved frustrating. Proposals such as creating a new class of light carriers would be far more costly and time-consuming than retrofitting existing CVNs.

Experimentation should include fusing manned and unmanned aerial systems, harnessing the ship’s nuclear power for energy-intensive weapons, integrating artificial intelligence, and configuring the hangar bay and flight deck to optimize storage, launch, and recovery of unmanned aerial vehicles. Having an experimental carrier for wargaming exercises and training with other ships in an “augmented carrier strike group” will allow the next generation of leaders to think beyond the limits of current doctrine, encouraging those who will fight the next war to shape the future of naval airpower.17

Even if the days of the CVN are numbered, experimenting with CVN(X) will help determine what modifications could ensure a robust support role for carriers. For example, what does a CVN optimized for defending itself and nearby surface combatants from missile attack look like? If a CVN needed to carry a large silo of cruise missiles, where should they be located to not interfere with flight operations? What combination of manned fighters, armed unmanned vehicles, and refueling and ISR aircraft best support distributed maritime operations? Without trial and error, the Navy is unlikely to arrive at the right answers.

Investing time and resources in carrier-based airpower amid doubts about its future is—to borrow a term made famous by Admiral Chester Nimitz—a calculated risk.18 But it is one the Navy must take before the shooting starts.

Editor's Note: The views expressed are written solely in the author’s personal capacity and do not represent those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

1. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Pursuing ‘Surface Development Squadron’ to Experiment with Zumwalt DDGs, Unmanned Ships,” USNI News, 28 January 2019.

2. See CAPT Robert F. Johnson, USN (Ret.), “Carriers Are Forward Presence,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 122, no. 8 (August 1996).

3. The British ships, dispatched to aid in the defense of Singapore at the start of World War II, were sunk by Japanese aircraft. See Barry Gough, “Prince of Wales and Repulse: Churchill’s ‘Veiled Threat’ Reconsidered,” Churchill Proceedings (remarks delivered at the 2007 International Churchill Conference, Vancouver).

4. “Limitation of Naval Armament (Five Power Treaty or Washington Treaty” (1922).

5. Norman Friedman, “How Promise Turned to Disappointment,” Naval History 30, no. 4 (August 2016).

6. Ernest Andrade Jr., “The United States Navy and the Washington Conference,” The Historian 31, no. 3 (May 1969): 345−63.

7. Albert A. Nofi, To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940 (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010).

8. Robert Farley, “No Contest: Why USS Enterprise Is the Best U.S. Navy Ship Ever,” The National Interest, 23 June 2017.

9. Norman Friedman, Winning a Future War: War Gaming and Victory in the Pacific War (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2017), 11–19, 73–108.

10. ADM John S. Thach, USN (Ret.), “Butch O’Hare and the Thach Weave,” Naval History 6, no. 1 (March 1992).

11. Clark G. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013).

12. James D. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal (New York: Bantam Books, 2011).

13. William H. Honan, “Return of the Battleship,” New York Times Magazine, 4 April 1982.

14. Charles E. Myers Jr., “A Sea-Based Interdiction System for Power Projection,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 105, no. 11 (November 1979).

15. Senator Bumpers is quoted in Honan, “Return of the Battleships.”

16. Edward J. Marolda and Robert J. Schneller, Shield and Sword: The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf War (Washington, DC: Government Reprints Press, 2001).

17. The term “augmented carrier strike group” derives from a distributed fleet proposal in a Navy report to Congress. Navy Project Team, Report to Congress: Alternative Future Fleet Platform Architecture Study (27 October 2016), 13.

18. Robert C. Rubel, “Deconstructing Nimitz’s Principle of Calculated Risk,” Naval War College Review 68, no. 1 (Winter 2015), art. 4.