The sea is unforgiving. Much like the sea, leadership in the Sea Services as junior officers can be unforgiving. The stakes and expectations are high. A lapse in judgment, even for a few seconds, can spell disaster. It is a lesson that junior officers often learn the hard way.

In my case, there was no denying it. I had screwed up. I was standing in the captain’s cabin, with my boss and my boss’s boss, and I was on the receiving end of an uncomfortable lecture. The captain was rightfully irate. The ship was deep in the Pacific Ocean as part of an expeditionary strike group. A major storm had been forecasted, and I was ordered to make sure all my division’s equipment was secure for sea.

I dutifully walked around the ship, blindly “inspecting” things, and then went on to the next task on my to-do list. There are always things for an ensign to do! It turned out everything was not secure, and a key piece of equipment was broken in the ensuing heavy seas.

During the captain’s lecture, which got more uncomfortable by the minute, someone suddenly stepped between the captain and me. I was surprised to realize it was my chief, who had been standing safely tucked in the corner of the cabin while I was in the hot spot. I was even more shocked to hear him tell the captain—with just a hint of indignation—not to blame the ensign. It was his job to secure the gear, and he should be held responsible. He then outlined the plan already in place to get replacement equipment on board during the next port call. The captain calmed, appeased by the plan of action, and I was not keelhauled.

That experience taught me that I had a lot to learn as a leader at sea. Mistakes happen, but you can overcome and grow from them. Perhaps most important, I learned about trust and doing what is right, even when it is not easy.

Leadership is hard, tiring, and full of hazards with no time-outs. “The difference between a good officer and a great one,” said Admiral Arleigh Burke, “is about ten seconds.” With competing demands, leading often can feel like a game of whack-a-mole; bouncing from one item to another “more” important requirement, only to quickly return to the first demand. So how do you measure success as a leader in the Sea Services? Is it mission success? Unit success? Personal success? Or something completely different?

Leaders Start with Trust

Retired Army General Colin Powell described trust as the essence of leadership.1 It is a powerful measure of success as a leader and a good gauge of leadership up and down the chain of command. Think back to the best leaders you have worked with during your career—not necessarily the most popular, or nicest, or coolest—but the leader you would want in charge in an emergency; the leader you knew would do what is right. That is trust.

Just because you have a gold stripe on your sleeve does not mean you are a leader. Becoming an officer gives you a license to lead, but you need to prove you are worthy of the task. Some people will do the bare minimum for an empty uniform with a rank on it. Instead, be an active leader and start building expertise.

The best aspect of trust-based leadership is that it is achievable at every level for a junior officer, and you can work on improving it. You build trust as a leader by being technically proficient and hungry to learn; by preparing yourself for unforgiving seas; and by taking active interest in the lives of those around you.

It is tough to build trust if you are not technically proficient. Ask any ensign the day he or she reports to their first unit, unqualified and unsure how to contribute. Take the case of Dr. Blanke—a character from C. S. Forester’s The Man in the Yellow Raft—who as a lieutenant (junior grade) in the Navy for only a few days during World War II found himself in command of a lifeboat after his resupply ship was sunk by a torpedo.2 Although a fictional story, it is something to which every new officer can relate. In Lieutenant Blanke’s case, he had recognized his knowledge deficiencies and dutifully studied the only resource he had available, The Bluejacket’s Manual.

Forester’s message is spot-on. Be a sponge and learn everything you can to gain expertise. Most qualification boards end with the newly qualified officer being told “Congratulations on your qual. You’ve demonstrated the minimum level of competency to stand the watch; now the real learning begins!” How do you learn more? Be proactive!

- Read books, ask questions, read articles, read manuals, seek out answers, listen to a podcast. Whatever your preferred learning medium, taking a few minutes each day to learn something new pays tremendous dividends in the long run.3 Check out two of my favorites: Captain V. S. Parani’s book, Golden Stripes: Leadership on the High Seas (Dunbeath, UK: Whittles Publishing Ltd, 2017) and Simon Sinek’s Start With Why (New York: Penguin Group, 2009).

- Master your primary duties. Collaterals need to be secondary. If your primary duty is X, you need to be an expert at X, not building a résumé of Y and Z collaterals.

- Teach others. Teaching requires you to master a topic. Never be the teacher who glosses over a topic that you do not understand.

- Invest in yourself. Want to learn more about the weather at sea? Take a meteorology class. Want to be a better ship handler? Take an advanced shiphandling class to grow as a mariner.

I worked with a great leader who told me that expertise is being able to execute basic tasks 100 percent of the time. Only then can you be trusted to move on to more advanced skills. As junior officers in the Sea Service, we need to be able to execute fundamental tasks safely and effectively to be professionals and earn trust.

Leaders Keep Learning

Once you hit the four-year mark of your Sea Service career, if you have been working hard, gaining experience, and practicing day-to-day leadership in your duties, it is tempting to get cocky and to start to coast. Don’t.

It is a common ensign error, for example, to show up just prior to a major evolution, like getting the ship under way, and only then to start thinking about the plan. A prepared leader will arrive early, review the weather, look at the track lines, consider all the elements, know the chart top to bottom, and have a plan and a backup plan that considers what could go wrong. Prepared leaders ask this critical question.

Leaders need to recognize problems before they become problems. “The mark of a great ship handler,” said Admiral Ernest King, “is never getting into situations that require great shiphandling.”

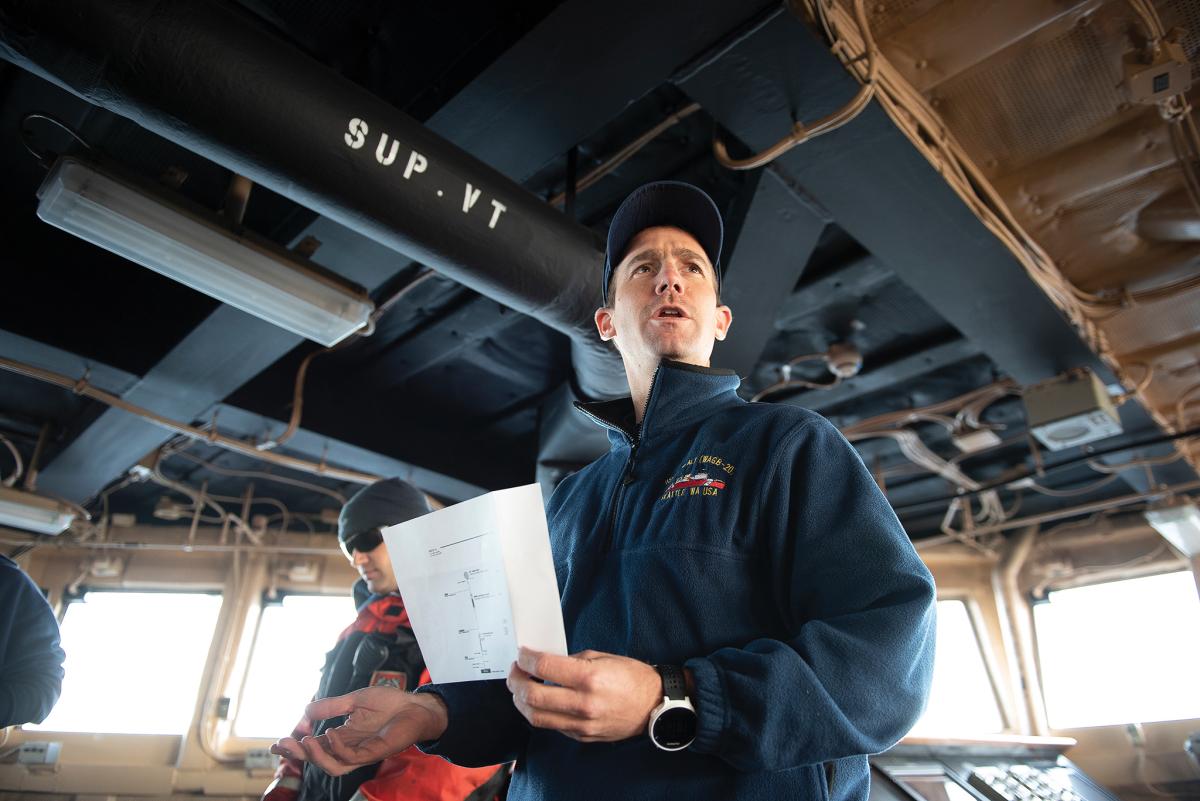

Once, while conducting a navigation brief prior to getting a ship under way, one of my subordinates gave a thorough and well-considered brief on his plan. When he finished, our captain asked a simple question, “What if you can’t get the stern away from the pier because the wind is too strong?” So, we discussed a contingency plan. When we went to pull away from the pier, the wind was too strong and the backup plan calmly was executed.

Learning does not end once you have become more senior. In reality, that is when to double-down and ensure you are ready to deal with the inevitable challenges ahead. So as your career progresses:

- Broaden your horizons. Start to ask how other organizations—government and civilian—do things.

- Do not repeat history, learn from it. Dig into MISHAP reports, case studies, and books, and ask, “What would I have done in that situation?”

- Challenge your subordinates. Do not accept a lackluster performance or bare accomplishment of a task.

Leaders Pay It Forward

As junior officers, we have to be positive and adaptable to lead and manage diverse units and people. If you hope to overcome the toughest challenges, it is paramount to take an active interest in the lives of those around you: A leader who is helping people achieve their own goals is better able to inspire subordinates to help the unit accomplish the mission. Without knowing people’s personal and professional goals, it is difficult to get everyone moving in the same direction.

Another invaluable resource for young leaders is mentors. Seek out people in your professional and personal life whom you respect, and never be afraid to ask for help. While seas can be unforgiving, mentors are lifelines. They help prepare you and offer advice before you even know you need it. For example, here is the advice one of my mentors sent to me right before commissioning:

You have a great deal of hard work ahead of you. You will make mistakes; learn from them and overcome them. You know what is wrong and what is right; do what is right. And yes, our people are the most important resource we have. Be a leader and mentor them. Do not just use corporate jargon and send them to [Leadership School]. Also, remember that looking after our people is not always pleasant and not everybody is a success story. Do not be afraid to make the hard decisions. The personnel decisions you make will make the future Coast Guard stronger or weaker.

I have referred to this advice countless times throughout my career, focusing on different sections at different stages and gauging whether I am measuring up. Now flip the coin. Just as I have, you undoubtedly have had mentors invest in you. Now, pay it forward and do the same. Whether it is nudging people in the right direction or pushing people toward resources or training, help them achieve their goals.

At the junior officer level, once trust is established, the potential of what a unit can achieve together is immeasurable. As Kenneth Dodson—a World War II naval officer who later penned popular novels about life at sea—put it in his best-seller, Away All Boats, “We don’t have to be great to have a share in greatness!”4 The reward earned from sea service leadership is the opportunity to look your efforts and results directly in the eye every day. Through preparation and building trust, we can be leaders who inspire the best people and overcome unforgiving seas together.

1. Colin Powell with Tony Koltz, It Worked for Me—In Life and Leadership (New York: HarperCollins, 2012), 76.

2. C. S. Forester, The Man in the Yellow Raft (Boston: Little Brown, 1969).

3. See ADM James Stavridis, USN (Ret.), and R. Manning Ancell, The Leader’s Bookshelf (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2017).

4. Kenneth Dodson, Away All Boats (Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1954).