In July 1943, at the time of the Invasion of Sicily, high level planning with respect to subsequent operations in the Mediterranean Theater had gone no further than a decision that a success in Sicily was to be exploited, with the means then available, in the best manner to bring about the early elimination of Italy. The details, which were largely left to the discretion of the Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean (SACMED), General Eisenhower, were to depend upon the extent of the Sicilian victory, subsequent political developments, and the latest intelligence as to the strength of opposing forces. The reduction of Allied Forces in the theater, both military and naval, by prospective transfers to the British Isles preparatory to the first priority Normandy Landing, scheduled for the following spring, was a further consideration.

The principal question, at first, was whether the objective was to be Sardinia or the mainland of Italy itself. As early as June 30, General Eisenhower had proposed a landing on either the toe of Italy, or on Sardinia, estimating that the latter might be undertaken by October, but that the former would not be practicable until November, at which time bad weather was likely to be prevalent.

The rapid progress of the Sicilian Campaign, coupled with the fall of Mussolini on July 25, greatly increased the prospects of a successful invasion of Italy, and the arguments in favor of this operation became overwhelming. Moreover, it became apparent that an earlier date would be practicable than had been originally expected. Given the decision, then, that the mainland was to be the objective, where and when should the landing, or landings, be made? In order to keep the enemy off balance after his Sicilian defeat and, furthermore, to complete the operation and secure a port before the advent of bad weather, an early date was important.

A jump across the Strait of Messina into the toe at Reggio was an obvious move, but the nature of the terrain would make an advance up the Calabrian Peninsula against determined resistance slow and difficult. A landing on the instep, in the Gulf of Gioja, as an adjunct to the Messina-Reggio landing, offered certain advantages. A landing on the heel, in the vicinity of Taranto, was another prospect. Other points in the Gulf of Taranto were considered. None of the landings in the extreme south of Italy, however, offered anything other than the prospect of a slow advance up the boot.

A landing on the west coast, well up the boot, if made in sufficient force, might trap defending axis forces to the southward. At the very least it would relieve the pressure on other allied forces advancing from the toe and heel. The chances of success, however, were entirely dependent on the forces available to the assault and the scale of enemy resistance to be expected.

Rome was a natural primary objective and it was desirable to land as near to it as possible. Its possession would ensure the Italian collapse and would also advance Allied aviation far enough north to strike well into important German-held territory. But no landing that far north was practicable, because it would be well beyond the range of air cover by Sicilian-based fighter planes. The capture of Naples was of extreme importance because of its excellent harbor, possession of which would be essential to the supply of large allied forces in Italy. But direct attack on the Bay of Naples, in view of its defenses, was out of the question. To the north of Naples, the Gulf of Gaeta offered fairly good beaches, but approaches and beach gradients were not good. This area, moreover, was beyond the range of effective fighter cover from Sicilian fields. To the south of Naples, however, the Gulf of Salerno offered a long stretch of beach, with excellent gradients for the most part and clear approaches. While fighter planes here would not be able to remain long on station, reasonable air cover was practicable, particularly if augmented by some naval aviation. From the military point of view, Salerno had the disadvantage that the whole beachhead area would be under enemy observation from the high land which ringed it and that an advance to Naples would have to be made over the high ridge which separated the Salerno from the Naples plain.

An early decision was made to carry out the movement into the toe (Operation Baytown) with General Montgomery’s Eighth Army, veterans of the desert campaign, and of the Sicilian East Coast landing. Planning was also initiated for an assault in the Gulf of Salerno (Operation Avalanche) by an Allied Force of some three or more divisions, an operation to be instituted in the event of favorable developments in the military situation. Concurrently and with higher priority, certain British Forces tentatively allotted to Avalanche were required to plan for Operation Buttress, the landing in the Gulf of Gioja.

The Commander of the Eighth Fleet and his operations staff, particularly the planning section, became involved in the discussion and study of these prospective operations as soon as they returned to Algiers from the Husky operation.1 For Avalanche, Lt. General Mark W. Clark, as Commanding General Fifth Army, was designated as the military commander. The command of the Allied Naval Force (Western Naval Task Force), which was to establish the Fifth Army on shore, was assigned to me. As it happened, I had known General Clark since 1938 when, as Inspector of Ordnance in Charge of the Ammunition Depot, Bremerton, Washington, I had dealt with him, then Corps Area Operations Officer at Fort Lewis, with respect to war plans and the antiaircraft defense of the ammunition depot. My relationship with General Clark continued to be most cordial and friendly throughout.

The Badoglio Government, which succeeded that of Mussolini, openly announced its intention to continue the prosecution of the war. But, almost immediately, it initiated clandestine communications with the Allies. The first overture came on August 3, via a special agent sent to Lisbon to gain contact with the British ambassador there. This resulted in a highly secret meeting in Lisbon between Italian emissaries and General Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, General Bedell Smith, and his Intelligence Officer, the British General Strong. These conversations continued until, at a final meeting held in Sicily on August 31, general agreement as to the terms of an Italian capitulation was reached. The Italians were most anxious to surrender, but feared the certain retaliatory action of the Germans, who were in practical occupation of their country. They wanted definite assurance that, before any announcement was made, strong allied support would be at hand. To safeguard the royal family and the government, they urged a landing north of Rome, and they felt that an Allied Force of some fifteen divisions would be needed—a force which they did not know was far from being available. They were quite willing to combat the Germans and requested that they be accepted by the Allies as co-belligerents.

Even before the completion of the Sicilian Campaign on August 17, it was evident that no further effective Italian resistance would be encountered and that a surrender was in the offing. This led to the Supreme Commander’s decision to carry out Avalanche and to cancel Buttress. September 3 was set as the date of Baytown while Avalanche was scheduled for September 9. A possible landing on the heel at Taranto was left in a tentative status, to be inaugurated if and when conditions were favorable and the means permitted.

The planning for Avalanche was greatly complicated by the wide separation of the principal commanders and their forces; by uncertainties as to the actual units to be allotted, both military and naval, and the short time available. As rapidly as decisions were reached on one echelon, they were passed out to subordinate commands by means of planning memoranda, with the result that, in some cases, final plans and orders were issued by various echelons almost simultaneously. There was a lapse of only two months between the “D” day for Husky and that for Avalanche, and the latter was to take place only twenty-three days from the close of the Sicilian campaign.

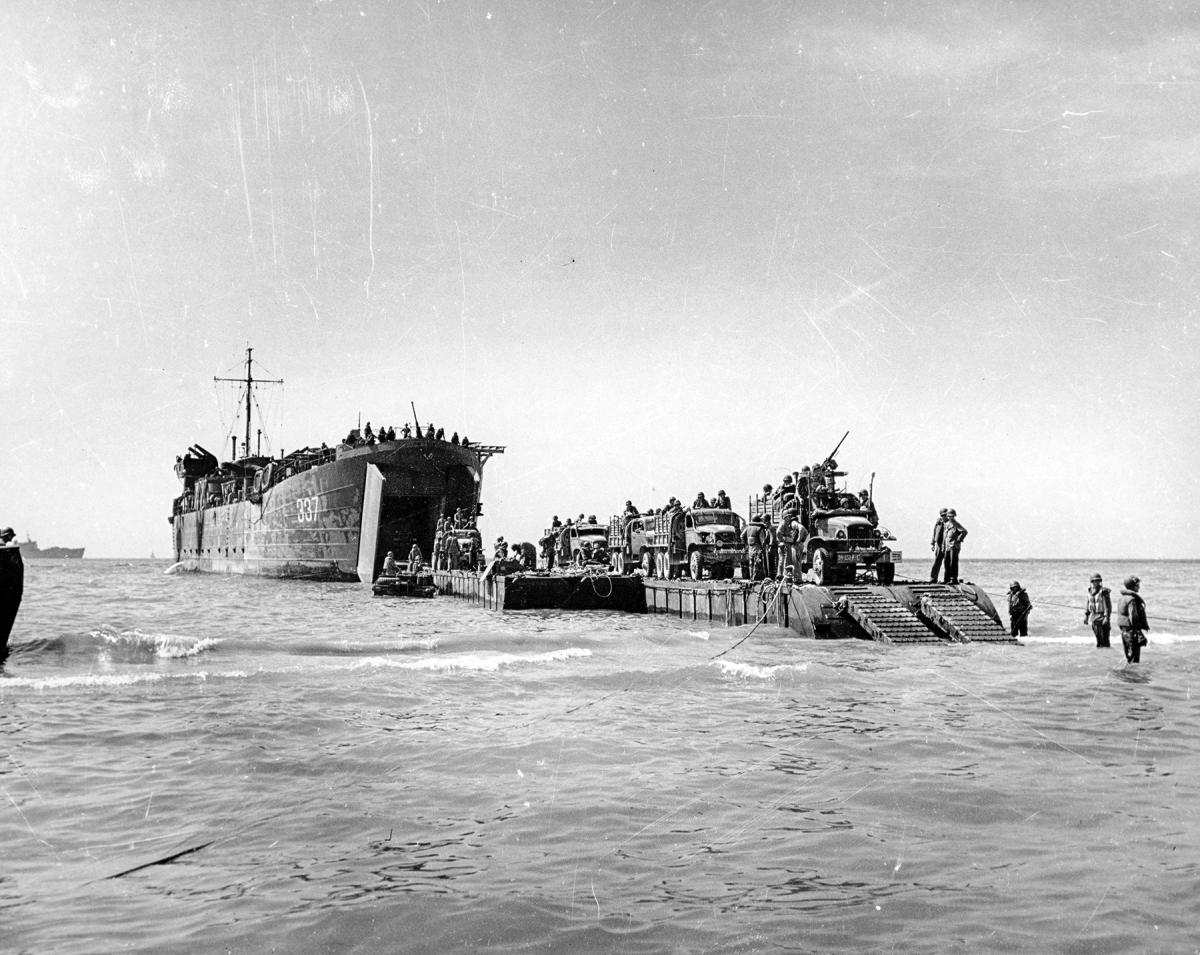

Another difficulty with which the Navy was faced was the timely withdrawal of landing craft from the Sicilian operation for the overhaul necessary to ensure reliability for the next major operation. These craft, particularly the LSTs, had been found to be so useful in support of the ground forces in Sicily, ferrying motor vehicles, supplies, and troops, that the Army was exceedingly reluctant to let them go. It took the very strongest of representations on our part to effect their release, and that at the very last moment. That they continued to perform well at Avalanche is a tribute to their crews and to the magnificent work done by the Eighth Fleet maintenance units, at Bizerta, the newly organized Palermo U. S. Ship yard, and the fleet repair ship Vulcan.

Assigned to the Fifth Army originally were the U. S. VI Corps (36th and 34th Infantry Divisions and the 1st Armored Division), the U. S. 82nd Airborne Division, and the British X Corps. To these, other units were added later. My initial directive from the Commander in Chief Mediterranean,2 dated July 31, gave me an estimate of the naval forces, both British and American, which, in addition to assault transports and landing ships and craft, were expected to be available for gunfire support, escort duty, minesweeping, motor boat patrol, and diversionary operations. Three British submarines were offered for beach finding and marking. This directive also nominated Commodore G. N. Oliver, R. N., an old hand at amphibious operations, as Task Group Commander for the assault to be carried out in British ships and craft, and U. S. Rear Admirals J. L. Hall and R. L. Conolly, both veterans of the Sicilian landing, and the former of Morocco as well, as Task Group Commanders for assaults to be carried out by U. S. shipping.

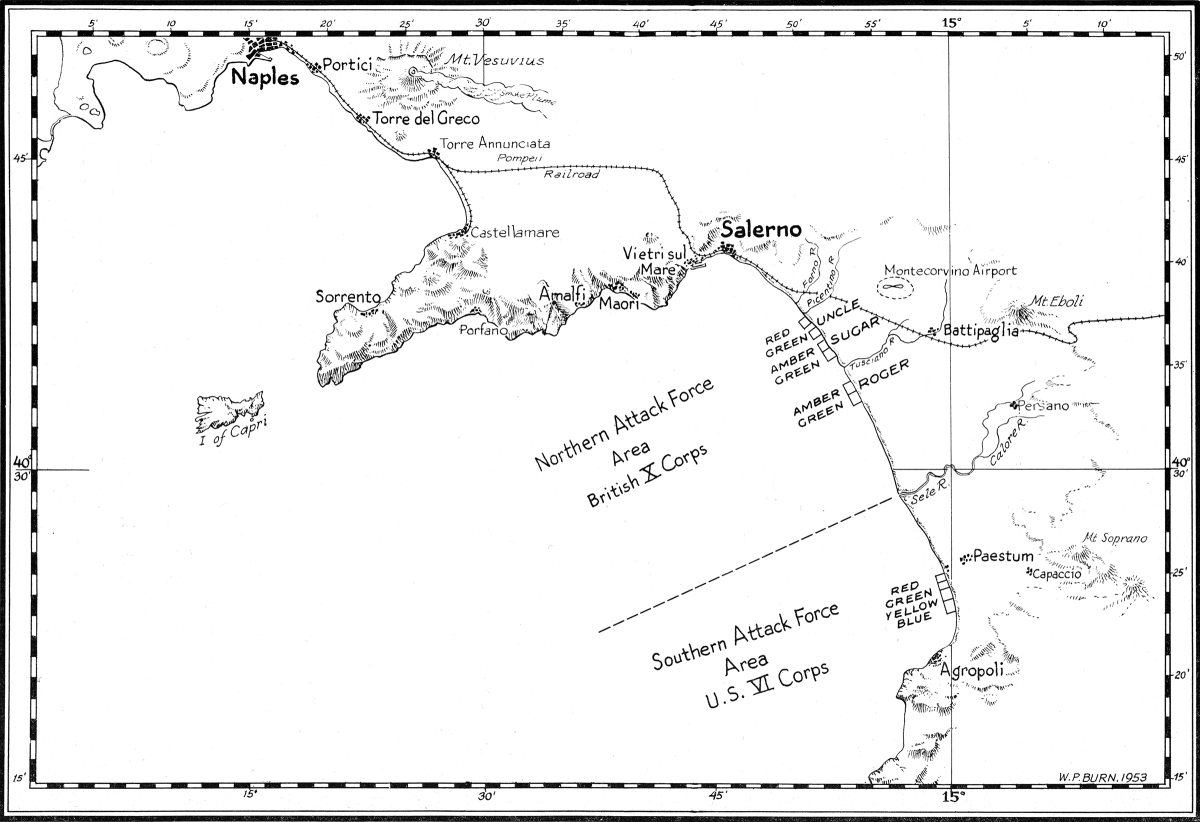

The Fifth Army Attack Plan provided for two major assaults, one by the British X Corps in the northern sector of the Gulf of Salerno, between the city of Salerno on the north and the Sele River which practically bisects the beach area; and the other by the U. S. VI Corps, south of the Sele River. The British attack was to be made on a two division front, while the American was to be made on a one division front. Attached to the British Force were three U. S. Ranger Battalions and two Royal Marine Commandos, all under the command of the famous Colonel Darby, which were to cover the left flank by securing the passes from Maiori and Vietri sul Mare over the mountains into the plain of Naples.

This organization of the Fifth Army Forces naturally led to the establishment of two corresponding naval Attack forces. The Northern Attack Force, under Commodore Oliver, would land the British X Corps and left flank rangers and commandos in the Northern Attack Area. The Southern Attack Force under Rear Admiral Hall (who was Commander of the Eighth Amphibious Force) would land the VI Corps in the Southern Attack Area. Necessary gunfire support, minesweeping, and escort groups would be assigned to each of these forces. Naval units assigned to the Northern Attack Force were primarily British, except that, of the 90 LSTs, 84 LCTs, and 96 LCI(L)s almost exactly half were American. Two salvage tugs and some other small craft attached to this force were also U. S. vessels. The Southern Attack Force was composed of U. S. vessels except for three small British cross-channel steamers (Landing Ships Infantry), three special type fast LSTs, the monitor H.M.S. Abercrombie, the anti-aircraft cruiser H.M.S. Colombo, and one or two minor craft. Troops would be carried in assault transports and cargo ships primarily but also in landing craft.

All the Eighth Fleet Landing Craft were normally under the command and administration of Rear Admiral Conolly, the Commander Landing Craft and Bases. He would have been the natural officer to assume command of the U. S. Craft assigned to the Northern Attack Force, except for the fact that he was senior to the British Officer commanding that Force. I therefore asked him to nominate one of his group or flotilla commanders for this command. Admiral Conolly’s reply was that he wanted this command for himself, and that he was perfectly willing to serve under Commodore Oliver’s orders. He was so assigned. This action on his part facilitated the operation, and greatly pleased our British Naval Allies. By this time the United States and Royal Navies in the Mediterranean were working together as one team with absolute mutual respect and confidence.

Since a British Cruiser Squadron was available to support the Northern Attack Force, U. S. Cruiser Division Eight, consisting of the Philadelphia, Savannah, and Boise, which was still attached to the Eighth Fleet, was assigned to the Southern Attack Force. Thus Rear Admiral Davidson, its commander, who had performed so splendidly in support of the Sicilian Campaign, was able to continue in this important work, which had become his specialty.

General Clarke established his headquarters at Mostagenem, where he could be in close touch with the 36th and 34th Divisions. Major General Dawley, commanding the VIth Corps and Major General Walker, commanding the 36th Division, were both in the Oran area, near Admiral Hall and his staff.

Of the divisions assigned originally to the VIth Corps, none had had prior combat or amphibious experience. The decision to land on a one corps front had been dictated by assault shipping limitations. Since the 36th Division was the first one available, this division was placed under intensive amphibious training by the Eighth Amphibious Force in the Arzeu area. The 34th Division was assigned as a reserve to be carried in the first follow up convoy. The veteran 45th and 3d Divisions, already in Sicily with General Patton, were also assigned to the VIth Corps for the operation. As much of the 45th Division as landing craft could be found to accommodate were to be embarked with the initial assault as a floating reserve.

The British Xth Corps was composed of the 46th and 56th infantry divisions with the 7th Armored Division as a Corps Reserve. The 46th Division was to be transported in landing craft from Bizerta, while the 56th Division was to be embarked from Tripoli in British landing ships, small fast assault transports, and in landing craft. Commodore Oliver, with his flagship the Hilary (In British “Combined Operations” terminology, a “headquarters ship”), was at Tripoli. Admiral Conolly, of course, was at his Landing Craft Base at Bizerta. During an air attack on Bizerta on August 17, General Horrocks, commander of the Xth Corps, was so badly wounded that he had to be replaced on August 22d by General Sir Richard Mc- Creery.

Rehearsals were held in each of the embarkation areas, Tripoli, Bizerta, and Oran. That of the 36th Division, in the Arzeu-Mostagenem vicinity, was observed by General Clarke and by me. None of them, due to the lack of availability of some of the units concerned, was as complete as could be desired. All units did the best with what they had in the time that could be allotted to them.

While practically all naval units assigned to Avalanche were well-trained veterans of previous amphibious operations, many army commands connected with the operation were engaged in their first real combat assignment. The Army service command which was given the responsibility at Oran of loading the assault transports and cargo ships of the 36th Division was not only unfamiliar with amphibious technique and the principles of combat-loading but exhibited little understanding of the authority and responsibilities of the commanding officers of naval vessels. The Army Transport Quartermasters, carefully trained by the Eighth Amphibious Force, were ignored. This led to unfortunate delays and controversies which should not have occurred. Furthermore, unsafe army loading of merchant cargo vessels (such as ammunition and cased inflammables in the same hold) conduced to losses which might otherwise have been avoidable. To me, the lesson is obvious—the responsibility for the war-time loading of assault and supply shipping should be given only to those who understand ships and cargoes and the hazards to which they are to be exposed.

Air planning was a great improvement over that for the Sicilian Invasion. Aircraft anti-submarine protection for the Western Naval Task Force, in the approach and during the operation was to be provided by the Northwest African Coastal Air Force. Fighter protection was also to be provided by this force until the Task Force arrived north of Sicily, whereupon this duty was to be taken over by the Northwest African Tactical Air Force, whose planes would be based initially in Sicily and, as soon as practicable, on captured Italian fields. Major General E. J. House, U.S.A.A.F., who proved to be most cooperative, was assigned to the flagship of the Commander Western Naval Task Force to exercise tactical control of aircraft supporting the Task Force. But, except for the carrier air units this time assigned to the Western Naval Task Force, the air set up had the same defect as that for Sicily, in that the Tactical Commander in the forward area had no direct control over any air units except those allotted from time to time at the discretion of another commander in a rear area. The Support Carrier Force, consisting of one British Fleet Carrier, the Unicorn, and four escort carriers, under Rear Admiral Vian of Altmark fame, was under my command. This force was to have the duty of reinforcing the fighter cover, particularly, in the morning and evening twilight periods, when the reliefs between land-based day and night fighters took place.

On the 3d of September, as scheduled, the British Eighth Army made the crossing of the Straits of Messina into Calabria (Operation Baytown). The operation was successful and met with only minor resistance. On this day also the first convoy for Avalanchf. left Tripoli. This consisted of 33 British LCTs with troops and equipment of the 56th division, scheduled to stage at Termini on the north coast of Sicily. This procedure was necessary on long trips with such craft as the LCTs and the LCI(L)s, since their accommodations for troops over an extended period were meager in the extreme. A similar convoy of U. S. LCTs, carrying units of the 46th Division, left Bizerta the following day to stage at Castellamare, west of Palermo.

At daylight on the 5th of September, a convoy of 34 British LCI(L)s left Tripoli for Termini, where it also was to stage. At 1500 of the same day, the 36th Division convoy under Rear Admiral Hall (NSF-1), departed Oran. This convoy consisted of nine Assault Transports (APA), four Assault Cargo Ships (AKA), three large fast British LSTs of the so-called “Killer” type, and 3 large British infantry landing ships (LSI(L)), under escort of three light cruisers (Crudiv Eight) eleven destroyers, eight minesweepers (AM), and one British Fighter Director ship. The movement of this convoy was promptly reported by enemy reconnaissance aircraft.

On this same day, there was transmitted to the Western Naval Task Force some very important intelligence. The first was as to the location of minefields in the Gulf of Salerno, information obtained by magnetic detection devices by reconnaissance of the British submarine H.M.S. Shakespeare, which was to act as beacon submarine, and which had been on station in that area since August 29. The second, which was also to be of particular importance, was a bulletin from the British Admiralty concerning two German radio-controlled bombs, one a glider type, giving information as to countermeasures to be used.

On September 6 (D−3), a convoy of twenty LSTs, plus store ships and auxiliaries sailed from Tripoli, en route to the Northern Assault Area in Salerno Bay. The LCTs en route to Sicily had had a hard night, and the U. S. LCTs had to move from Castellajnare to the more sheltered Carini Bay in order to fuel. There, thirteen stragglers joined, and one craft had to be sent to Palermo for repairs. The Ancon, Flagship of the Western Naval Task Force, with General Clark and his staff aboard, the fighter director ship, H.M.S. Palomares, and three destroyers left Algiers and joined Convoy NSF-1 as it passed. The Minelaying Group, three U. S. minelayers, under Commander Mentz, U. S. Navy, escorted by three British Hunt class destroyers, left Oran en route to Bizerta, where they were to await a possible call to establish a protective minefield in Salerno Bay. Commodore Oliver, on the Hilary, with nine British infantry landing ships with suitable escort departed Tripoli in the afternoon, and an LCI(L) convoy got underway from Bizerta. In the late afternoon, a large LST convoy sortied from Bizerta and anchored in the outer harbor, thus, with the aid of smoke cover, escaping a raid by about 180 planes on Bizerta at 2030. By this time, practically all the Western Naval Task force was on the move.

During the afternoon an order was received from the Commander in Chief Mediterranean inaugurating Operation Slapstick, a quick movement by cruisers to carry the First British Airborne Division from Bizerta to Taranto to seize and hold that port and a neighboring airfield. For this purpose the British 15th Cruiser Squadron was detached from the Northern Attack Force, and the U.S.S. Boise from the Southern Attack Force. Three cruisers of the 12th Cruiser Squadron replaced the 15th. This required considerable last minute rearrangement of the gunfire support plans of both the Northern and the Southern Attack Forces.

On September 7, D−2, everything continued more or less uneventfully as planned. German aerial reconnaissance was active. The Bizerta LST Convoy (FSS-2) proceeded on its way toward the assault area at first light. Crudiv Eight stood in to Bizerta to take on board aviation fuel and their observation planes which had been based there. Intelligence was received that large numbers of Dornier-217s, planes suitable for daylight bombing of shipping, were being moved from the south of France to the Foggia air fields, just across the Appenines from Salerno. At 2230, Commodore Oliver’s convoy was heavily attacked by torpedo bombers, but fortunately no damage was done.

Some landing craft staging on the north coast of Sicily departed for the assault area on the 7th. The remainder left on the following morning, the 8th (D−1). Welcome news was received from the gallant Shakespeare that she had sunk a U-boat on patrol in the Gulf of Salerno, but less pleasant news that there were two more in the vicinity. Throughout the day of September 8 there were many interceptions of enemy sighting reports on our gradually converging convoys. Air attacks on the landing craft convoys which, due to their slower speeds, were in advance, began as early as 1400. The British LCT 624 was hit and sunk at 1650.

At 1830, September 8, official announcement of the Italian Armistice was received and published to all hands in the Task Force. This information was naturally most welcome, but it had a bad psychological effect on some of the troops, who got the idea that they were going to be able to walk ashore unopposed. Responsible officers realized that the Germans would probably be present in strength and put up a most effective resistance, as was the case. As a matter of fact, the Germans had gained advance information of the prospective Italian capitulation, had disarmed the Italian troops with whom they were in contact, and had manned the important defensive positions with their own forces. By the same course of reasoning which had governed its selection, the Germans had deduced that Salerno would be the Allied objective and had acted accordingly. The convoy movements reported by their aerial reconnaissance were merely confirmatory.

During the course of negotiations with the Italians, in order to provide them with support concurrently with the announcement of the armistice, it had been proposed to drop the 82nd Airborne Division, under Major General Matthew Ridgway, on the airfields near Rome, with the object of securing those fields and possibly the city itself. This was a bold plan which required complete military co-operation by the Italians, who, of course, for security reasons, could be told nothing of the main attack plan. Brigadier General Maxwell Taylor made a daring undercover preliminary visit to Rome, under the noses of the Germans, to perfect the necessary arrangements. Unfortunately, this plan had to be cancelled at the last moment, because the Germans, apparently smelling a rat, moved in and took the fields over themselves with a strong defensive force. In accordance with the final plan, the 82nd Airborne Division was to be brought into the beachhead area after the initial assault as a reserve.

Beginning with D−7, the Northwest African Strategic Airforce had carried out a series of heavy attacks against enemy airfields within support range of the prospective assault area and against enemy lines of communications connecting with that area. As with other operations of this nature, the attacks had to be delivered over a rather wide range to avoid premature disclosure of the actual objective.

By 2000 of September 8, the Northern and Southern Attack Forces of the Western Naval Task Force, with minesweepers ahead, were making their respective approaches to assigned positions and areas in the Gulf of Salerno, in readiness to land troops at the chosen “H” hour, 0330. Once again, the assault was being made under cover of darkness without prior naval bombardment, except for a minor one in the Northern Area just before the landing. A Diversion Group under Captain C. L. Andrews, Jr., U. S. Navy, consisting of the destroyer Knight, two Dutch gunboats, the Soemba and Flores, six motor launches, four subchasers, and five motor torpedo boats, equipped with deceptive devices and carrying a small detachment of troops from the 82nd Airborne Division, were en route toward the Gulf of Gaeta to make a feint demonstration off the beaches near the mouth of the Volturno River and to capture Ventotene Island, on which there was a German radar station. A Picket Group of sixteen PT boats, under Lieutenant Commander Stanley M. Barnes, U. S. Navy, whose task was to guard the northwest flank of the task force against enemy small boat attack, was heading into the Bay of Naples. The Italian Fleet, in accordance with the Armistice terms, was en route via prescribed routes to Malta, to surrender, thus making unnecessary the support of the strong British Battleship-Cruiser Force “H,” which had assumed a position to cover the Western Naval Task Force against attack by a major surface force. On shore, the Eighth Army was pressing forward from the toe, and intelligence reported heavy enemy traffic moving northward on all the roads from the southern tip of Italy.

The landing craft and other shipping of the Northern Attack Force continued to come under heavy air attack throughout its approach to the Northern Attack Force Transport Area (NAFTA). In the course of these attacks five or six Junker-99s were shot down, but no further damage was done to the Allied forces. While the attacks on the Northern Attack Force were clearly visible from the ships of the Southern Attack Force, with which the Task Force Flagship Ancon was in company, this force escaped attack. The beacon light of the Cole, which had been sent ahead to contact the Shakespeare, and that of the Shakespeare itself, were sighted by 2200.

On September 9, “D” Day, shortly after midnight, the transports and assault craft of both the Northern and Southern Force had reached their lowering positions and began disembarking troops. In view of uncertainties caused by the announcement of the armistice, I transmitted the following to the Western Naval Task Force at 0146: “An armistice with Italy has been declared. Operations now in progress vigorously proceeding as ordered, but Italian armed Forces, including aircraft, should be treated as friendly unless they take hostile action or threaten hostile action. Plans for covering fire on beaches are to proceed as ordered, but coast defense batteries should not be engaged unless they open fire.” Shortly after 0200, however, fire was opened from ashore against shipping in the Northern Attack Area, resulting in a hit with severe casualties on U. S. LST 357. The Biscayne laid a smoke screen and the British destroyers Brecon and Blankney promptly engaged the shore batteries. Minesweepers were encountering many mines, and many drifting mines were sighted in the swept channels. Intelligence announced that an enemy reconnaissance plane had reported the arrival of Allied shipping off Salerno at 0035. A report was received that Ventotene Island had surrendered without resistance at midnight.

At 0315, fifteen minutes before “H” hour, as scheduled, fire support groups of the Northern Attack Force opened gun and rocket fire on the northern beaches. As requested, there was no preliminary fire on the VIth Corps beaches. The first waves at all beaches landed within a few minutes of the “H” hour, none being more than twelve minutes late. Enemy reaction was almost immediate, and opposition was reported on all beaches. The assault beaches were designated as indicated on the map on page 963.

Although successful landings were made on all beaches, the difficulties encountered during this first day were many. The Xth Corps, possibly helped by the preliminary beach bombardment, met little initial opposition but soon ran into stiff resistance and a tank counter attack. The VIth Corps in the south ran into trouble at the start, finding enemy tanks in position behind the beaches. Troops on the southern two beaches, Yellow and Blue, were pinned down practically all day. The Rangers had little difficulty at Maiori, but the Commandos, after getting ashore safely at Vietri, were driven off. Finally, with the aid of the Rangers, they recovered Vietri and ended the day in possession of the city of Salerno.

On the naval side, initial operations were handicapped by the large number of mines encountered. Gunfire support in some instances was delayed by the necessity of sweeping the support cruisers and destroyers into positions sufficiently close in shore. These mines also delayed the beaching of landing craft, particularly LSTs, and the moving of transports in close to reduce boating time. One LST carrying pontoons struck a mine off the Uncle beaches and had heavy casualties. An observation plane from Philadelphia was employed after daylight to spot mines and mark positions with smoke floats.

Air attacks started early, 0417, and continued in strength throughout the day and into the night, some twelve or more in all. The U. S. tug Nauset was hit in the first attack and again at 0615, when it was sunk. The minesweeper Intent was damaged by bombing and by the explosion of the Nauset. Other shipping was damaged. The British cruisers Uganda and Delhi collided and damaged each other in a smoke screen during an evening air attack in the Northern Area. While most of the attention in these attacks appeared to be devoted to the Northern Area, the Southern Area did not escape. Valiant work was done by the fighter cover, without which the effect of these many attacks would have been much more serious. Through General House, commanding the XII Air Support Command, appeals were made for heavy Allied attacks on the fields the enemy planes were using—Naples, Benevento, and Foggia.

The beaches were under heavy enemy artillery fire throughout the day, which not only resulted in many casualties, but in considerable damage to landing craft and LSTs. In some cases, beaching was delayed. There was at least one instance of a beached LST engaging enemy tanks. The southern VIth Corps beaches, Yellow and Blue, were closed down and were out of communication for part of the day. Beaches became congested with craft waiting unloading by troops which were not at hand for the purpose. Some had to be retracted under gunfire, still loaded. Others were unloaded by working parties scraped up from the already overworked transport crews.

Throughout the day, the naval gun fire support vessels of both attack forces were fully engaged. Cruisers, destroyers, the monitor Abercrombie, and the LCG (landing craft, Gun) did valiant and effective work. Without them, the picture would have been very dark. It was naval gunfire that permitted the VIth Corps to open its right flank Yellow and Blue beaches again. The feeling of at least one general was expressed in the following message, addressed to Admiral Davidson: “Thank God for the fire of the Blue Bellies’ Navy Ships. Probably could not have stuck it out on Blue and Yellow beaches. Stout fellows. Please tell them so.” The Abercrombie, unfortunately, was mined and damaged in the late afternoon.

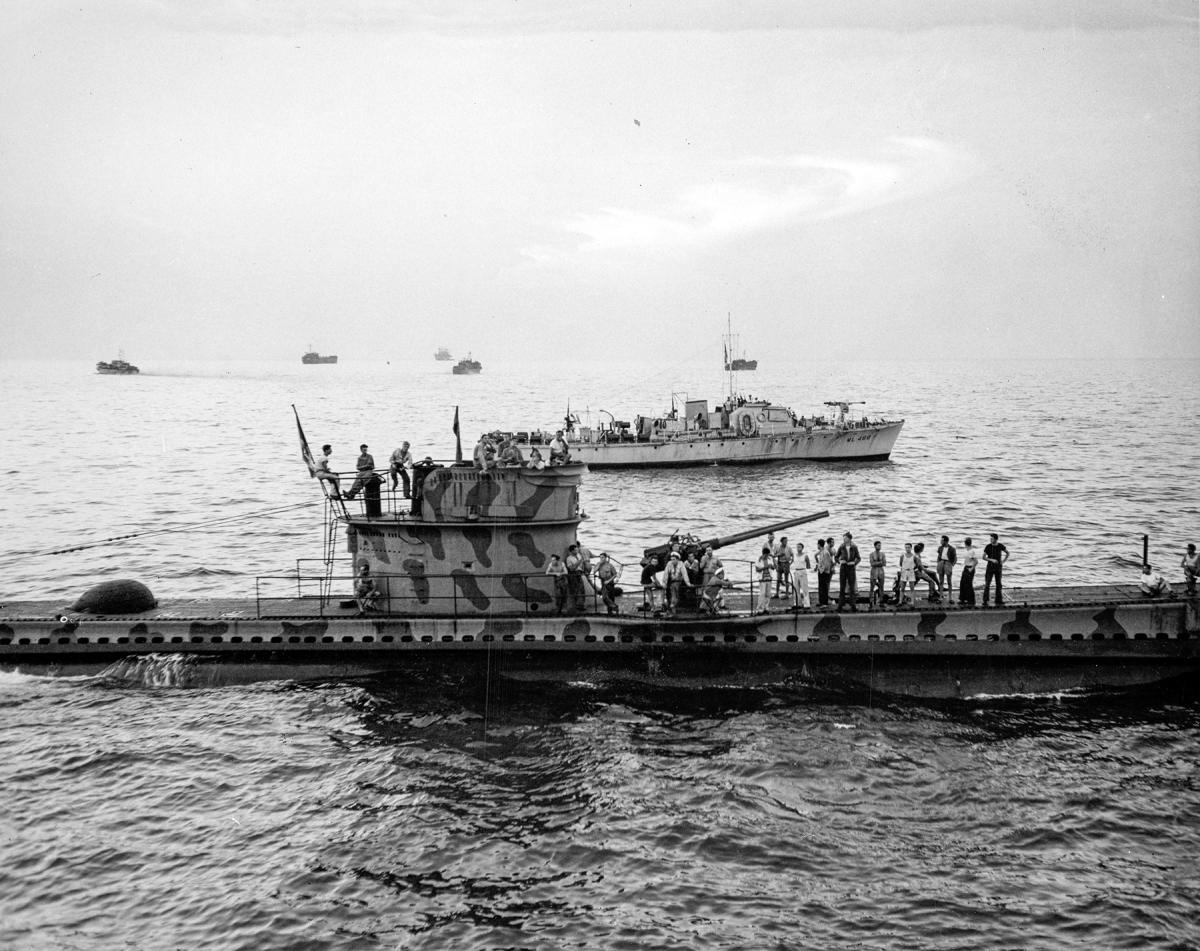

Elsewhere during the afternoon the new Italian battleship Roma, flagship of their battlefleet, which was leading the fleet units from Genoa, La Spezzia, and Leghorn, down the west coast of Corsica, en route to Malta, was attacked by German aircraft, blown up, and sunk with heavy loss of life, including the Italian Admiral. Thus the Germans dealt with their erstwhile ally. About the time this was happening, our outer patrols picked up the Italian submarine Nickel, which was proceeding south on the surface to carry out the armistice terms. For its own protection, I had it brought alongside the Ancon, where it was naturally the object of much curiosity. The very smart young commanding officer reported in person to me and, speaking excellent English, demanded that he be permitted to carry out his orders to the letter, which were to proceed to Malta, via Messina. I explained to him that, for his own safety, I could not let him proceed unattended, that I would report his presence with me, and that I would sail him in the middle of the first convoy we despatched. This was done that night, after we had taken the precaution to render his armament harmless.

On this same day, September 9, the Boise and British cruisers carrying the First British Airborne Division, covered by the battleships Howe and King George V, reached Taranto and disembarked their troops without resistance. Unfortunately the cruiser-minelayer Abdiel, at anchor in Taranto Harbor, swung over a mine dropped by a German E boat and sank with considerable loss of life among troops and crew.

In the Salerno Area, September 10 (D+1) commenced with an air attack between 0100 and 0200, before the moon set. These attacks were resumed at first light and continued throughout the day, the last attack occurring just before midnight. Some fourteen attacks were delivered during eight daylight hours. That only minor damage was done was due to the splendid work of the fighter cover, including the Seafires from the carriers, and the effective use of smoke cover. Over twenty enemy planes were reported as having been shot down. In spite of this air activity, and the request by General House for an extra P-38 squadron from 1630 to last light, the Commanding General of the North African Tactical Air Force, from his position back in Tunisia, was proposing that fighter cover be reduced in favor of increased fighter bomber attacks on enemy road communications.

Throughout the day of the 10th, the troops ashore continued slowly to enlarge the beach head, albeit against bitter resistance. The Xth Corps captured Battipaglia, but later was driven out. They were not able to secure the much-desired airfield at Monte Corvino. Salerno had been taken and a port party sent in. In the south the situation of the VIth Corps was confused and was not satisfactory to General Clark. Elements of the 45th Division were being landed from LCIs on Red Beach to support the 36th. The beach situation was somewhat cleared up in so far as opposing artillery was concerned, but all beaches were badly congested by the inability or failure of the Army to provide sufficient troops to clear them of stores and unload waiting landing craft. One beachmaster went so far as to refuse to accept any LCVPs that were not accompanied by working parties. Gun fire support vessels were actively engaged during the day in firing on targets requested by the troops.

Minesweeping was continued throughout D plus 1, and a cruiser plane was again used to spot mine positions. It was intended to leave the enemy minefields to seaward of the transport areas to serve as anti-submarine protection. This was done in the Southern Area, only certain approach channels being swept. In the Northern Area, however, through a misunderstanding, Commodore Oliver had the entire seaward approach cleared. In the south, some 66 mines were detonated or otherwise destroyed during the day.

At 2210 of September 10, having completed the unloading, the large APAs and AKAs of the Southern Attack Force departed for North Africa, under the command of Admiral Hall. They were ordered to proceed to Algiers and there await further orders, there being a possibility that they might-be required to bring in reinforcements. Smaller convoys, for Tripoli and Bizerta, had departed the Northern Attack Area at intervals throughout the day. Admiral Conolly in the Biscayne was ordered from the Northern Attack Area to take over command of the Southern Area, a duty similar to that which he had so well discharged at the Sicilian landing. My flagship, the Ancon, although she would be the only large ship left and therefore a conspicuous and tempting target from the air was of necessity retained, particularly as General Clark and his headquarters staff had not yet landed.

In view of information received that there was a considerable nightly flow of heavily laden enemy cargo shipping north of the Gulf of Gaeta, operations by PT boats and destroyers to interrupt this traffic were initiated.

September 11, D plus 2, opened with the usual daylight air attack, determined attacks being made in both the Northern and Southern Areas. General House with my complete approval, had previously despatched the following reply to the Tactical Air Force proposal that fighter cover over the assault area be reduced: “We have given every consideration to the desirability of making aircraft available for fighter bomber action. Our policy has been to provide no more cover than requirements dictate. No changes should be made in cover commitments until fighters are based on Avalanche. Monte Corvino may not be ready for a few days. It should be ready late 11 September or on the 12th.”

At 0130, the U.S.S. Rowan, escorting Admiral Hall’s convoy, drove off two enemy E boats. While rejoining the screen, she was torpedoed, probably by E boat, and sunk with great loss. The survivors were picked up by the Bristol.

It became evident during this day that the enemy had come to realize fully the effect that naval gunfire was having on his attempts to repel the invasion. In a determined effort to eliminate it, he began attacks on gunfire support vessels with the latest weapons at his command, those of which we had been warned less than a week before. At 0935, the Philadelphia, in the southern fire support area, was near missed by a glider or rocket bomb. The bomb struck to starboard within fifteen feet, and the very heavy explosion shook up the whole ship. Six minutes later, from a position on Ancon not 500 yards away, I heard and saw a bomb strike the Savannah right in the middle of #3 turret. The bomb penetrated to and below the handling room before it detonated, and then it blew the bottom out of the ship. The venting of the explosion was plainly visible along the port side water line abreast the forward turrets. This hit not only put the ship out of action, but it killed practically everyone in the turrets and below decks forward of the bridge. As the bow gradually settled and the stern came up, grave fears were felt for the ship itself. She was saved by the magnificent work of the survivors of her own damage control parties (the Damage Control Officer and all in the central station were lost) and the officers and men of the salvage tugs which were quickly in attendance. Four men trapped below in the auxiliary radio room, with flooded compartments above and all around, were kept alive by their own courage and ingenuity and by efforts made from above to supply them with air and food, and were eventually rescued in good condition when the ship finally reached Malta.

These radio controlled bomb attacks were launched from planes flying at some 21,000 feet, concurrently with a lower level ordinary bombing attack apparently designed to draw off the fighter cover.

Faced with the loss of the Savannah, damage to the Philadelphia and to the Dutch gunboat Soemba, which had been hit earlier in the day, and the very evident threat to the remaining gunfire support vessels by this new weapon, it was apparent to me that the situation was extremely critical. Affairs on' shore were in such a precarious state that any failure in the “floating artillery” would be almost sure to tip the balance against us and result in our troops being driven into the sea. At about the same time, I received word from Admiral Vian that “my bolt will be shot this evening, possibly earlier” and requesting permission to retire his force that night to Augusta for refuelling of his destroyers.

My first action, after reporting the casualty, was to request of the CinC Mediterranean that he return the Boise to me immediately and that he ask for maximum air coverage for us. He complied at once. General House sent the following to the HQ North African Tactical Air Force:

“Admiral Hewitt protesting reduction of coverage. Suffering losses that cannot be replaced. Urgently recommend original plan until further instructions.”

To this HQ NATAF replied at 1130, two hours after the disastrous hit on Savannah:

“Unable to understand statement that Admiral Hewitt suffering losses which cannot be replaced and request further details. We have no report of these losses and our information from you indicates light enemy air attack which has been well handled by patrolling fighters. We have no information of effectiveness of operation of Seafires (Carrier planes). Agree very reluctantly to return of P-38 squadron to defensive fighter yoke and will arrange forthwith.”

In justice to all concerned, it seems certain that the foregoing was sent before the news of the attacks on the Philadelphia and Savannah had been received. But the incident does illustrate the time lag in communications and the dangers of decisions being made in a rear area for a front line commander who is the one best able to appreciate the immediate tactical situation. I realized fully that a 100% effective air defense was impracticable and that some successful enemy attacks must be expected. But, given the overriding importance of maintaining the naval gunfire upon which the army was then relying for the retention of its narrow foothold on the beach, I did think that this was certainly no time for the reduction of fighter cover over the ships. I am a strong believer in unity of command, particularly in tactical operations. Tactical unity of command implies that a tactical commander should have under his own control all the available instruments necessary to the successful accomplishment of his mission.

As the day wore on, I sent the following to Admiral Vian:

“Air situation here critical. Status air field ashore uncertain. Can your carrier force remain on station and furnish early morning cover tomorrow?”

To which he promptly replied:

“Yes, certainly. Shall just be able to reach Palermo. Augusta plan cancelled.”

Other air attacks occurred during the day, most of which were intercepted and broken up. But there was little rest for the weary anti-aircraft gun crews and many others who had been at battle stations almost constantly from the start of this operation.

The situation on shore changed little during the day. The VIth Corps position was somewhat improved, but the Xth Corps was held up.

It was known that photographs of the anchorage area off the Salerno beaches had been taken during the day by high flying enemy camera planes. Enemy conversation was intercepted that made it apparent that a large ship in the southern area had been pin-pointed as the major target for a night attack. This ship was unquestionably the Ancon. After weighing the pros and cons of accepting attack at anchor with the advantage of possible smoke cover and the massed antiaircraft fire of adjacent vessels, or of proceeding to sea after dark in an effort to escape observation, the latter was decided upon. The ship put to sea at about 1930, under escort of two destroyers, zig-zagging at twelve knots, in order to make a minimum of wake but still be reasonably secure against submarine attack. The air attack on the anchorage, which came between 0235 and 0340 of the 12th, was observed from seaward, but the Ancon was not spotted, greatly to the disappointment, according to intercepted conversations, of the enemy aviators. A store ship was hit and set on fire. By daylight, the Ancon was back in place and had resumed the fighter director control, which had been temporarily turned over to the Hilary.

The Savannah sailed for Malta under suitable escort, after dark of the 11th and eventually reached port safely.

At 1000 of September 12, (D+3) General Clark transferred ashore, establishing his, headquarters in the VIth Corps Area. Admiral Vian had been released by me about 0800 and duly thanked. Later during the day, his Seafire fighters were flown to the fighter strip at Paestum, which had by then been made ready. The Monte Corvino field was still under enemy bombardment and unusable.

Some air attacks continued throughout the day, and a rocket bombing attack was reported in the Northern Attack Area.'It was considered that smoke would be one of the best means of defense against radio controlled bombs, since the launch was made at high altitude and the bomb and target had to be kept in sight throughout the fall. Plans were also made to determine and attempt to jam the control wave. Steps were taken to bring up all available smoke material from North Africa, and arrangements were made to make smoke, either from smoke pots on the beach or from destroyers and small craft to seaward, depending on the wind.

Since the Headquarters of the Fifth Army had disembarked and the role of the Commander Western Naval Task Force had become a supporting one, it became desirable to retire the valuable Ancon from the Assault Area. Accordingly, with a small operations staff, I moved in on the Biscayne with Admiral Conollv, as I had done before at Sicily. The Ancon was despatched to Algiers after dark, under the escort of two destroyers.

By September 13 (D plus 4), the Fifth Army was generally on the defensive. The British 56th Division had been driven out of Battipaglia with severe losses. The left flank of the VIth Corps, south of the Sele River, had also been withdrawn. Monte Corvino Airfield was still untenable. Most of the U. S. 45th Division was now ashore and the British Armored Division was beginning to land behind the Xth Corps. Resumption of an offensive, however, would have to await the arrival of more combat troops.

Follow up convoys with reinforcements, equipment, and supplies were arriving on schedule and LCTs in numbers were being used to unload store ships. The left flank Uncle beaches of the Xth Corps were again under artillery fire. The port of Salerno, while in our hands, was unusable because the entrance was commanded by enemy artillery. Naval gunfire was in demand throughout the beachhead area. Troops of the 82nd Airborne Division were scheduled to be brought in by air to the Paestum strip in the early evening.

In the morning twilight hours of the 13th, the hospital ships Leinster and Newfoundland, which had been sent to sea for the night (fully lighted) and which were returning to the Gulf of Salerno, were bombed and hit by enemy planes. The Leinster, fortunately, escaped serious damage, but the Newfoundland was set on fire, and had to be abandoned, the personnel being rescued by other hospital ships and by attending destroyers. The fire on the Newfoundland was fought by destroyer crews and by Commodore Sullivan and his salvage crews who were sent out to assist. Commodore Sullivan was authorized to sink the ship if effective salvage appeared impracticable. This he reluctantly did, after working all day and far into the night.

During the day, the gunfire support group suffered another severe loss. The British cruiser Uganda, which had survived previous collision injury, was hit and severely damaged at 1440 by a rocket bomb. There was no air alert in effect at the time, and the plane was unseen. The Uganda was effectively put out of action and, after nightfall, was despatched to Malta under tow of the U. S. tug Narragansett. Shortly after this attack, the Philadelphia was near-missed by a glider bomb. Half an hour later, she was again near-missed by a similar bomb. With this sort of thing happening, can it be wondered that concern was felt as to our ability to maintain the all important gunfire support?

In addition to Ventotene, Capri and other islands off the Bay of Naples had by this time been taken over by our Diversion Group. The Army Garrison Commander on Capri and the Commander of the Italian Motor torpedo Boats based on that island reported to me via U. S. PT boat and volunteered full cooperation. The former guaranteed the defense of the island and the latter was all for joining right in with our own PT Squadron. Since Capri was normally dependent on Naples for most of its watei supply, and that was now inaccessible, we suddenly became responsible for supplying the civilian population of Capri with its minimum water needs, an additional strain on our resources.

In view of the expected arrival of airborne troops at Paestum after dark, it was necessary to issue a positive order to ships in the southern area to withhold all anti-aircraft fire until after 2400. Of course, no smoke or barrage balloons could be used either. This left the shipping in the southern area in an absolutely defenseless position, but this disadvantage had to be accepted in order to insure the safety of our transport planes.

Elsewhere, things of interest were happening. We intercepted a request in French for bombers to be sent to Ajaccio, which was about to fall. With the Italian collapse, hostilities had commenced between Italian troops in Sardinia and Corsica and the small German garrisons there. The Italians asked for help. To meet this situation French troops were hastily loaded on French cruisers, which had recently arrived at Algiers after having been refitted in the United States, >and were despatched to the scene at high speed. A deficiency in anti-aircraft armament on one of these cruisers, the Jeanne d’Arc, was partially remedied by the hasty mounting of some available 40 mm. and 20 mm. guns by repair parties of the U.S.S. Vestal. Our French friends marveled at the rapidity with which this was done by our bluejackets.

By September 14 (D+1) a serious view was taken of the general situation. The enemy was making a determined drive down the Sele River valley with armored elements which threatened to break through to the beach and thus drive a wedge between the Xth Corps and VIth Corps. By use of his radio controlled bombs, he was making a threatening effort to eliminate naval gunfire support. Thus, the situation ashore and afloat was far from favorable.

At this time, General Clark requested me to make plans for the evacuation of the VIth Corps and its re-landing behind the Xth Corps, or vice versa, the evacuation of the Xth Corps and its re-landing behind the VIth. This was a difficult problem on the naval side, and we naturally did not like it. We presented the difficulties to the Fifth Army staff and pointed out, among other things, that it was quite different beaching a loaded landing craft and retracting it light from beaching it light and retracting it loaded. Having submitted the naval disadvantages, however, it was our duty to meet the desires of the Army as best we could.

As a preliminary step, I directed the Ancon, which had almost reached Algiers, to reverse course and proceed at best speed to Palermo, in readiness for possible recall to the assault area. In the event that the Fifth Army staff had to be re-embarked, there was no other vessel which could adequately accommodate them. In addition, I called in Commodore Oliver for a conference, acquainted him with the situation, and asked him to make such provision as he could on the Hilary for the accommodation of General Clark and his staff, in the event that they had to be re-embarked before the Ancon could reach us. Both he and General McCreery were bitterly opposed to any re-embarkation.

The British opposition to the withdrawal and re-embarkation plan is thoroughly detailed by Admiral Cunningham in his book A Sailor’s Odyssey. He apparently failed to realize that I was equally unhappy about it. Fortunately, very fortunately I believe, subsequent developments made it unnecessary to attempt it.

A step taken on the 14th in preparation for a possible withdrawal from the southern beaches was the temporary stoppage of unloading of store ships in the southern area and their being put on half hour notice for movement to seaward beyond range of shore artillery. In the early afternoon, the liberty ship Bushrod Washington was hit by a rocket bomb and set on fire, and an LCT alongside was damaged. Survivors were rescued by landing craft. Salvage tugs were promptly alongside to fight the fire, but the ship was eventually lost when it exploded and sank early the next morning.

Admiral Cunningham had already despatched the cruisers Aurora and Penelope to reinforce the gunfire support group, and upon my query as to whether heavier naval forces might be made available, ordered the battleships Valiant and Warspite to report to me. He told me that he was ready to help me all he could and that Nelson and Rodney were also available for my use, if required.

Full scale unloading of merchant store ships in the Southern Area was resumed on the morning of the 15th (D+6). One of these, the liberty ship James Marshall with an LCT alongside, was hit and set on fire at 0740 by a rocket bomb. The ship was promptly abandoned by its merchant crew, but the fire was extinguished by salvage tugs. The LCT eventually sank. The crew of the Marshall got ashore and could not be found to reman their ship, which was finally taken over voluntarily by the crew of the Bushrod Washington.

Air attacks, as usual, continued sporadically throughout the 15th. The British destroyer Derwentdale was damaged below the water line in the engine room by a near miss and had to be sent to Malta in tow.

The Valiant and Warspite arrived and promptly got their improvised gun-fire observation parties ashore and joined in the shore bombardment, the former being assigned to the northern area and the latter to the southern.

The Ancon reached Palermo, loaded all the available reserve 6" ammunition, and, in accordance with my orders, continued to Salerno. A destroyer was sent from Palermo to Malta to bring up ammunition taken from the Savannah. The Air Force, through the C. G. XIIth Air Support Command, was requested to provide a high altitude patrol to intercept rocket bomb carriers.

Early in the morning of September 16, (D+7) General Alexander, General Eisenhower’s ground force commander and the commander of the Fifteenth Army Group, arrived on a British destroyer. I met him on board and then escorted him ashore to General Clark’s headquarters. En route, I gave him the latest information I had of the Fifth Army situation, and he gave me my first details of the events in Sardinia and Corsica, where the Italians were actually fighting the Germans. “The whole world,” said he, “has gone crazy.”

Air activities on the 16th commenced with a night raid in which H.M.S. Lookout was near-missed by a rocket bomb and an enemy plane was shot down. The Philadelphia was attacked at first light but missed and other attacks, eight or more, occurred during the day. The most serious attack took place at 1427 just after I had drafted, but not yet sent, a despatch to the Valiant announcing that her services and that of the War spite would no longer be required after completion of the day’s bombardment and that I intended to return them to Augusta after nightfall. In this attack, the War spite was near-missed by one radio-controlled bomb and received direct hits right alongside the stack from two others, which penetrated the firerooms below and blew out the bottom. All firerooms were flooded, and except for one diesel generator, there was no power on the ship. All available salvage parties were sent to her at once and she was finally enabled to depart for Malta after dark, under tow of the tug Hopi. This fine ship had carried out three highly successful bombardments in support of the VIth Corps. Upon her departure, I sent her a special message of regret for her casualties and of appreciation for her splendid work.

It was possible to dispense with the services of the battleships because the military situation on shore was beginning to ease and because the long range targets for which they had been particularly needed had been more or less eliminated. Because of the improvement of the situation, it was also possible, to our great relief, to cancel the withdrawal plans. The abatement of pressure on the Fifth Army was to a large extent probably due to the approach of General Montgomery’s Eighth Army. Patrols of these two armies first made contact in the southeast sector of the beachhead line, slightly before dark on this day.

The Ancon had arrived in the forenoon, and my flag had been returned to her. The Boise, after nightfall, had to be despatched to Palermo for fuel and ammunition. The Paestum air strip being now available for use, Admiral Davidson was asking that four specially trained P-51 fighter planes be flown there for use in gunnery observation. This development had been the result of our Sicilian experience, where it had been found that the slow and comparatively defenseless cruiser SOC planes were all too vulnerable to attack by enemy fighters. With the cooperations of the Army air force a small P-51 group was put in training at Bizerta with the Cruiser Observation Squadron for spotting duty. This procedure proved to be a great success, the planes operating in groups of two, one spotting and the other covering.

September 17 (D+8) was marked by a welcome visit from Admiral Cunningham who arrived in a British destroyer. After his call on the Ancon, I accompanied him to the Hilary in the Northern Area, where we had Luncheon with Commodore Oliver. The situation was fully discussed. The military position on shore continued to improve, but the port of Salerno and the left flank Xth Corps beaches were still subject to enemy artillery fire.

Air raids were continuing but were becoming less effective. Much of our fighter cover was by this time based on near by fields, and we were perfecting the use of smoke cover. The Philadelphia was again attacked by two glider bombs and two ordinary bombs, but escaped damage. One ordinary bomb fell within a few yards of the Ancon. The Orion was near missed. Naval gunfire support cruisers and destroyers continued throughout the day to fire on targets as requested by the Army.

By the 18th (D+9) things on shore began to look still better, although enemy artillery was bothering the Uncle beaches and the port of Salerno could not yet be opened. It was an inspiring sight to see our old friends of the 3d Division, veterans of the Casablanca landing and of the Sicilian campaign, rolling up to the front, having been brought in from Sicily by our landing craft.

The Supreme Allied Commander, General Eisenhower, paid us a visit, and I had the pleasure of escorting him ashore to General Clark’s trailer headquarters, set up in a grove of trees in the VIth Corps Area. After a conference with General Clark, we visited a gun battery, which was tossing shells at the enemy over a nearby ridge, and a field hospital which was doing splendid work. Even that early, in the midst of all the bombing and shellfire, Army nurses had arrived to care for and comfort the wounded.

Stores and equipment for the Fifth Army, which, with a few exceptions, had been coming steadily by merchant ship convoy and landing craft ferry since the first days of the assault, now began to arrive in increased volume. Cruisers were continuing their daily bombardment, but, except on the left flank around Salerno, the ranges were getting longer. Admiral Davidson transferred his flag to the Boise, and, after dark, despatched the Philadelphia to Bizerta for ammunition and fuel. The Brooklyn, returned to the Eighth Fleet after the repair of mine damage suffered in the Sicilian landing, was due to arrive in the area on the 20th.

Air activity continued at the usual tempo. Anti-aircraft battery crews were kept at their stations, and the long red alerts considerably slowed unloading. Outside of that, no damage was done thanks to the effectiveness of the fighter cover and the smoke haze we were using.

There being no further apparent need for the Ancon to re-accommodate General Clark’s headquarters, I shifted my flag once more to the Biscayne before dark on September 19 (D plus 10), and after dark sent the Ancon to Palermo, where it was to stand by.

September 20 passed with little of note. By the 21st the operations of the Western Naval Task Force had been reduced primarily to the reception and unloading of convoys and the despatch of returning empty shipping, which duties were being handled most effectively by Commodore Oliver and Admiral Conolly, each in his own area. The duty of gunfire support, except for the northern flank, was gradually becoming of lesser importance and, in any event, was in the efficient hands of Admiral Davidson. General House, commanding the XIIth Air Support Command, had moved ashore and was controlling the fighter cover from his headquarters there. It therefore appeared to me that I could best further the task of my force by leaving Admiral Conolly’s little flagship to him, and by returning to the Ancon at Palermo. There, with better communications and facilities, I would be in excellent position to direct and co-ordinate future activities. Accordingly, leaving a senior and experienced officer as liaison officer with General Clark’s headquarters, I shifted my flag to the destroyer Nicholson at nightfall of the 21st and departed for Palermo. The trip down was enlivened by a brush with a submarine, which was detected by radar at 7500 yards, but unfortunately submerged before we could approach sufficiently close and which managed to elude the Nicholson in spite of an extended search. This submarine used a device new to us at that time, a float with a balloon supported antenna which made an excellent radar decoy. The ruse was not discovered until the ship ran it down and turned on searchlights ready to open fire. I arrived at Palermo and re-hoisted my flag on the Ancon by 0730 the. next morning.

It is interesting to observe that in spite of the fact that there were always submarines in the approaches to Salerno and that several successful attacks were made on shipping proceeding to and from that area, no submarine ever penetrated to the anchorage areas off the Salerno beaches. With the recollection of the torpedoings at Fedhala, Morocco ever present in my mind, the antisubmarine protection of shipping being unloaded off the beaches was always a source of concern to me. It was for that reason that a protective minefield was planned and actually laid around the anchorage area off Gela, Sicily. And it was for that reason that, in Avalanche, a mine laying group was held in readiness at Bizerta, to be called up if needed. The very effective minefield laid by the enemy in the approach to the Salerno assault area, in spite of the gap opened contrary to my intent by the Northern Attack Force sweepers, made further minelaying unnecessary. The gaps were guarded by reinforced surface patrols.

About this time, Rear Admiral Conolly received urgent orders to report to the Commander in Chief U. S. Fleet, ostensibly for further duty in the Pacific. I was sorry to lose his efficient services, but I knew that his experience in the Mediterranean would be extremely valuable on the other side of the world. I was equally sorry at the prospective loss of Admiral Hall, who was to go to the United Kingdom in command of the Twelfth Amphibious Force, preparatory to the Normandy landing. No better officer could have been picked for that duty. Rear Admiral Frank J. Lowry, U. S. Navy, who had been commanding the Moroccan Sea Frontier, was ordered to relieve Admiral Hall as Commander Eighth Amphibious Force, which was to include Admiral Conolly’s previous duty as Commander Landing Craft and Bases. Admiral Lowry reported to me on the Ancon on September 22, and on the 23d proceeded to Salerno to take over from Admiral Conolly. Commodore B. V. McCandlish, U. S. Navy, replaced Admiral Lowry as Commander Moroccan Sea Frontier.

On September 24th and 25th, the Fifth Army requested that consideration be given, first to the landing of a Regimental Combat Team in the Gulf of Gaeta, north of Naples, and when that was not deemed feasible, a similar landing in the Bay of Naples between Castellamare di Stabia and Torre Annunziata. The former was not favored because of the heavy mining of the Gulf and consequent sweeping requirements, coupled with multiple bars and irregular depths off shore and shallow beach gradients which would permit the landing of small landing craft, LCVPs and LCMs only. The latter was not considered practicable without undue loss because minesweeping in the approaches had not progressed sufficiently to permit free movement by gun fire support vessels and because the beach and the entire line of approach could be commanded from the heights of the Sorrento Peninsula, which had not yet been gained by the Allies.

On the 25th (D+16), Salerno was finally pronounced out of range of enemy gunfire, the port party was ordered in and the port was pronounced open. Two merchant vessels were berthed there that day. The Uncle beaches were still under gunfire.

On September 28, there was good news on the military and air sides, but bad on the naval. Advance elements of British armored units entered the plain of Naples and Castellamare di Stabia was captured. The Foggia airfield was occupied by General Montgomery’s Eighth Army, thereby removing the base from which most of the enemy air attacks on Salerno had been delivered. On the other hand, a warning that bad weather could be expected in the Gulf of Salerno during the night of the 28-29th was broadcast by the Commander Western Naval Task Force. When it came, it was worse than predicted. Commodore Oliver reported, “Heavy squalls of gale force causing grief.” In the Southern Area, which was the most exposed, 2 LSTs,

1 LCI(L), a British coaster, 25 LCTs, and 58 smaller landing craft were driven ashore. To the great concern of the Fifth Army, unloading was brought to a standstill throughout the 29th, and could not be resumed until the next day. We were very fortunate that this bit of weather, not unusual at that time of year, had not come earlier.

On the afternoon of September 29th, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, with three aides, arrived in Palermo by air from Algiers on a trip of inspection. He was met at the airport by General Patton and me, as well as by Admiral Davidson, who was present with his flag in the Brooklyn, and Captain Leonard Doughty, who was in command of the Naval Operating Base Palermo. After dinner on the Ancon, which was attended by General Patton and his chief of staff, Admiral Davidson and Captain Doughty, I embarked with the Secretary’s party in the Nicholson for Salerno, which was reached the following morning. Then began a strenuous day for the Secretary. Landing at the Port of Salerno, we were met by General Clark who took us to his headquarters and thence on a tour of the area, including the much fought over and badly damaged town of Battipaglia. The Secretary was most anxious to go right up to the front lines, but General Clark would not permit it. Returning to Salerno, we reembarked and had lunch on the Hilary with Commodore Oliver. From there, we proceeded by PT boat to Capri, where we were entertained by Rear Admiral J. A. Morse, R.N., who was there standing by to take over the Port of Naples. (A channel into Castellamare di Stabia had already been swept the night before.)

Admiral Morse, interestingly enough, was occupying the erstwhile villa of Countess Edda Mussolini Ciano, well up on the heights, from which there was a splendid view of the Bay of Naples and of Naples itself. While having tea in the garden, we were able to observe the smoke of German demolitions, presaging an imminent departure. By 2000 that night, we were back on the Nicholson returning to Palermo, from which the Secretary and party departed early the next morning, October 1. That same night, the Fifth Army entered Naples. It was too bad that the Secretary, so soon to succumb to the burden of his responsibilities, was denied the pleasure of entering with it.

With Naples occupied, I placed my able second, Admiral Davidson, in command of the Forward Echelon of the Western Naval Task Force and, on October 2d, returned in the Ancon to Algiers, where important Eighth Fleet administrative business awaited me. On October 6th, Admiral Cunningham formally dissolved the Western Naval Task Force, its task having been completed.

Thus ended Avalanche, an operation which was daring in its conception and the successful completion of which marked the beginning of the end for Hitler. As was officially stated by me at the time and has since been acknowledged by German military writers, the margin of success at Salerno was carried by the naval gun. But, without the gallant, determined, and efficient efforts of the fighter pilots of the Royal Air Force, the U. S. Army Air Force, the Royal Navy Air Arm, and the bombers who repeatedly attacked enemy airfields, the naval gun could not have been continued in action. The story of Salerno illustrates what can be accomplished against great odds by real interservice co-operation.

In tribute to the splendid services of the officers and men of the nations who served under me in the Western Naval Task Force, British and Dutch as well as American, I can do no better than to quote the words of Admiral Cunningham in his official report:

“That it [Avalanche] succeeded after many vicissitudes reflected great credit on Admiral Hewitt, U.S.N., his subordinate commanders and all those who served under them. That there were extremely anxious moments cannot be denied—I am proud to say that throughout the operation the Navies never faltered and carried out their tasks in accordance with the highest traditions of their Services. Whilst full acknowledgment must be made of the devastating though necessarily intermittent bombing by the Allied Air Forces, it was the naval gunfire, incessant in effect, that held the ring when there was danger of the enemy breaking through to the beaches and when the over-all position looked so gloomy. More cannot be said.”

1. See “Naval Aspects of the Sicilian Campaign,” by Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, in the July, 1953, Proceedings.

2. Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham, now Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope.