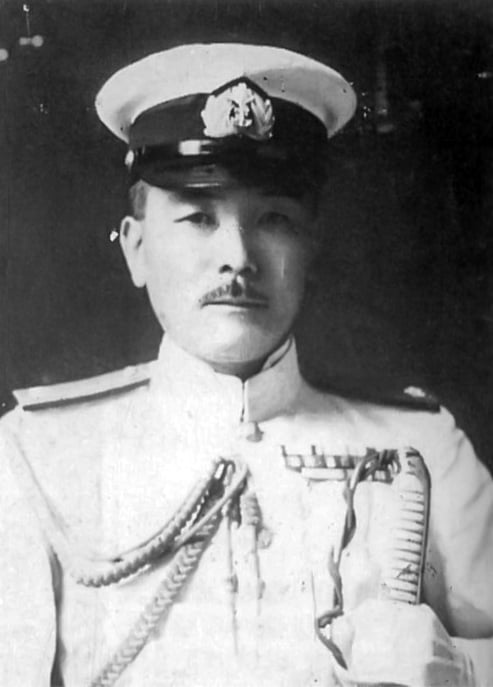

In 1944 I was chief of staff to Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, Commander in Chief of the Second Fleet of the Japanese Navy. Built around powerful battleships and cruisers, this fleet constituted the First Striking Force (sometimes translated, First Diversionary Attack Force), which was the main attack force in the Battle for Leyte Gulf. Many critical accounts of this battle have been written, and I do not mean to challenge them. I wish only to recall and review the course of events and describe the battle as I saw it. Although wounded twice within two days, I was with Admiral Kurita throughout the battle, always in good position to see what transpired. It is my hope that this essay may be of some value in clarifying the Battle for Leyte Gulf.

In June, 1944, the Japanese Navy suffered a devastating defeat in the fateful Battle of the Philippine Sea. We had to give up our hoped—for decisive battle and withdraw to Okinawa for fuel before returning to Kure. There the operations staff was called to Tokyo to report on the battle and confer regarding future operations. We had counted so heavily on a great victory to swing the tide of war in our favor that no plans had been prepared for the next move. Now Combined Fleet and Imperial General Headquarters were both at a loss as to what to do. It was certain, however, that the Second Fleet must go to Lingga Anchorage because fuel necessary for training was not available in Japan.

At Lingga Anchorage, on the eastern coast of central Sumatra, we had trained in early 1944, only to lose three aircraft carriers and most of our carrier planes in the June battle. Now what remained of that fleet was at Kure where all ships were being prepared to depart from the homeland, all, that is, except Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa's Mobile Fleet, whose carriers were offensively useless until planes and trained pilots became available. Meanwhile the fall of the Marianas was imminent as American attacks were increasing in intensity. It was estimated that the next big enemy offensive would come within three or four months, and it was hopeless to think that our carriers could be restored to fighting strength in that time.

Under these circumstances, only our Second Fleet and land-based air forces would be available for the next operation. But considering the low combat efficiency and reduced strength of our air force and the difficulty of cooperation between it and the fleet, it was clear that the latter would have to bear most of the burden. It also appeared that our next sea battle was likely to be our last.

We spent two busy weeks at Kure before starting for Lingga. For the first time, radar was installed in all battleships and cruisers. Anti-aircraft guns were mounted on every available deck space. The work was carried out in grim determination with the knowledge that there would be no friendly air patrol for the next battle.

The First Striking Force arrived at Lingga in mid-July. On August 10 the operations officer and I flew to Manila for a conference. A member of the Naval General Staff predicted, in a situation estimate, that the next big enemy operation would be in the Philippines in late October. The senior staff officer of Combined Fleet Headquarters presented the SHO [Victory] Operation order, which was, in outline, as follows:

Make every effort to discover enemy invasion forces at maximum distance (approximately 700 miles) by means of land-based air searches, and determine the enemy's landing place and time as early as possible so as to permit our forces to get into position for battle. The First Striking Force should be moved up to Brunei, North Borneo, in sufficient time to rush forward and destroy the enemy transports on the water before they disembark their troops. If this fails and the transports begin landing operations, the Attack Force will engage and destroy the enemy in their anchorage within at least two days of the landing, thus crippling the invasion effort.

The First and Second Air Fleets will first surprise at tack the enemy carriers with a view to reducing their strength, then, two days before the arrival of our surface force, will launch all-out attacks on the carriers and transports and thus open the way for the First Striking Force to approach and engage the enemy.

Questions, answers, deliberations, and discussions followed. Disturbed at the idea of hurling our Attack Force in wherever the enemy attempted to land, instead of using it in a decisive engagement, I asked: "According to this order the primary targets of the First Striking Force are enemy transports, but if by chance carriers come within range of our force, may we, in cooperation with shore-based air, engage the carriers and then return to annihilate the transports?" This question was answered affirmatively by Combined Fleet Headquarters.

Once the plans were clear, fleet training began at Lingga; with emphasis on the following points:

- Anti-aircraft action. Enemy air attacks must be repelled solely by our shipboard fire power. Every weapon, down to and including rifles, must be used at maximum efficiency for this purpose.

- Evasive maneuvers against air attack. We practiced fleet ring formations and mass maneuvering as well as individual ship movements to evade bombs and torpedoes.

- Night battle training was stressed as a possible opening to a decisive fleet engagement. Special emphasis was placed on night firing of main batteries with effective use of star-shell and radar. Aggressive torpedo attacks were also worked out and tested.

- Battle within the enemy anchorage. There were many problems to be worked out on this point, such as how to break into the anchorage where enemy shipping would be massed; how to destroy the enemy screening force; and how to attack the transports.

During our three months' stay at Lingga the training progressed most satisfactorily. We were fortunate in having unlimited fuel available from Palembang, Sumatra. Our radar sets were the best available. And thanks to the guidance and assistance of electronics experts from the homeland, who worked night and day in training radar operators, the sets were dependable and accurate in locating targets, and valuable in increasing the accuracy of our heavy caliber gunfire.

While training continued, high ranking officers made studies of various locales and tactics. There were three likely landing points in the Philippines: Lamon Bay in the North, Leyte Gulf in the middle, and Davao Gulf in the south. Passages and pertinent topographical data were carefully analyzed. Fleet instructions and methods of approaching these areas were diligently studied and deliberated, and there were frequent conferences.

Such large-scale penetration tactics as confronted us had never been practiced in peacetime. As the studies progressed, the difficulties of our task became more apparent. But training gave us confidence that we would be able to withstand enemy air attack, and the idea developed that we could put up a good fight. We felt sure that the problem of penetrating the anchorage could be solved.

The Combined Fleet policy that our force should destroy enemy transports at anchor, and not engage his carrier task force in decisive battle, was opposed by all of our officers. The United States fleet, built around powerful carrier forces, had won battle after battle ever since attacking the Gilbert Islands. Our one big goal was to strike the United States fleet and destroy it. Kurita's staff felt that the primary objective of our force should be the annihilation of the enemy carrier force and that the destruction of enemy convoys should be but a side issue. Even though all enemy convoys in the theater should be destroyed, if the powerful enemy carrier striking force was left intact, other landings would be attempted, and in the long run our bloodshed would achieve only a delay in the enemy's advance. On the other hand, a severe blow at the enemy carriers would cut off their advance toward Tokyo and might be a turning point in the war. If the Kurita Force was to be expended, it should be for enemy carriers. At least that would be an adornment for the record of our surface fleet, and a source of pride to every man.

Our greatest fear was that our planes might not locate the enemy at maximum search radius, in which case our force would be unable to reach the transports before they began unloading. If our attack should be delayed until several days after the enemy invasion, then judging from past experience, his transports would be emptied by the time of our arrival. It would be foolish to sink emptied transports at the cost of our great surface force!

While we tried to break into the anchorage, the enemy carrier forces would rain incessant air attacks upon us, and probably force us to a decisive engagement before we could even reach the transports. Thus top priority should be given to engaging the carrier striking force of the enemy.

Our officers were of the opinion that the Commander in Chief, Combined Fleet should come from the homeland and personally command his fleet at this crucial phase of the war. Many officers also complained about Combined Fleet's basic policy and expressed the hope that the operation order would be modified. But since it was an order, there must be no talk of changing it, and we should comply without hesitation or question. Outwardly I rejected all complaints of this nature, but inwardly I under stood and sometimes even agreed with my officers.

In short, our understanding was that we were to make every effort to break into the enemy's anchorage, but If the enemy striking force came within range, then we would carry on a fleet engagement.

I still believe that Combined Fleet understood this to be our operational policy, because it had been fully explained in Manila and was later submitted in writing. But our whole force was uneasy, and this feeling was reflected in our leadership during the battle.

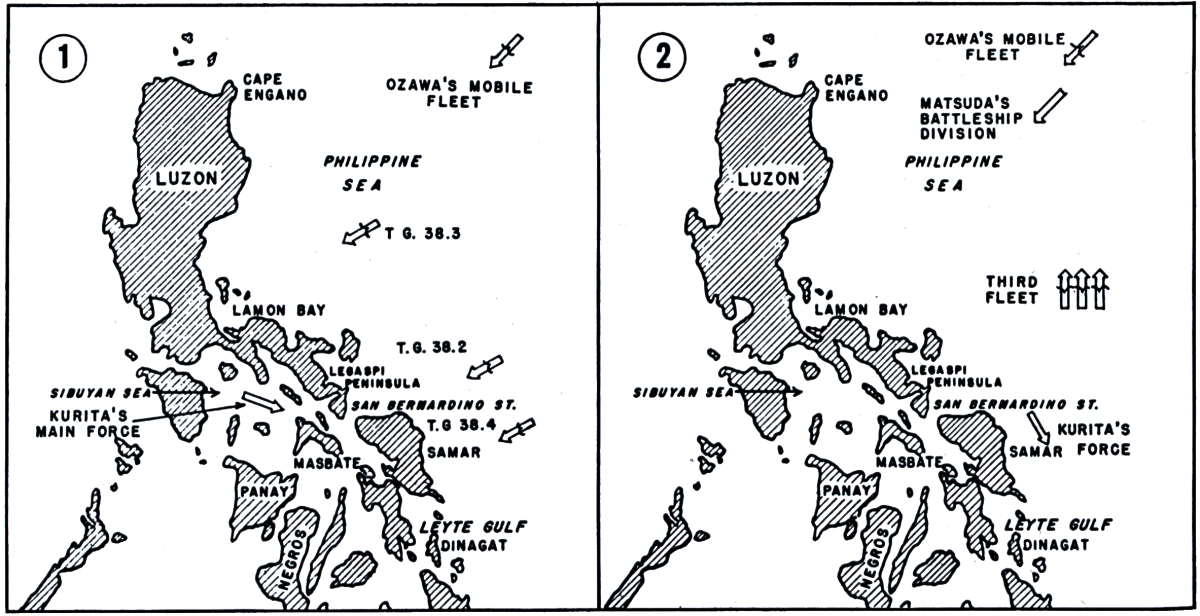

In the early morning of October 21, 1944, we received a Combined Fleet order to break into Tacloban Anchorage at dawn on October 25 and there destroy enemy ships. There were three routes from Brunei to Leyte Gulf.

- Through Balabac Strait, east into the Sulu Sea, and into Tacloban Anchorage through Surigao Strait.

- North through the Sulu Sea, transit San Bernardino Strait, turn south along the east coast of Samar, and approach Tacloban from the east.

- North through Palawan Passage, into the Sibuyan Sea, pass through San Bernardino Strait, and head south along Samar to Tacloban.

Analyzing these, we found number one was the shortest course to our objective, but it was within range of Morotai-based enemy search planes and would expose us to attack for the longest time. Number three was beyond enemy search plane range and offered less chance of encountering carrier air patrols, but it was the longest route and it passed through the narrow Palawan Passage, a favorite hangout of enemy submarines. Number two was a compromise between one and three.

Combined Fleet suggested that we approach in two groups, from the north and south, and it was accordingly decided that Admiral Kurita would take most of the ships via the third route, while a detachment of two old battleships and four destroyers under Vice Admiral Nishimura took route number one. These groups were both to reach Leyte Gulf at dawn of the 25th, a difficult achievement in itself considering the treacherous currents in narrow straits which each had to navigate. Timing was complicated by the great distances between the routes. And then there were the dangers of lurking enemy submarines and powerful enemy surface fleets. If concerted action was impossible, each force would carry out its attack alone.

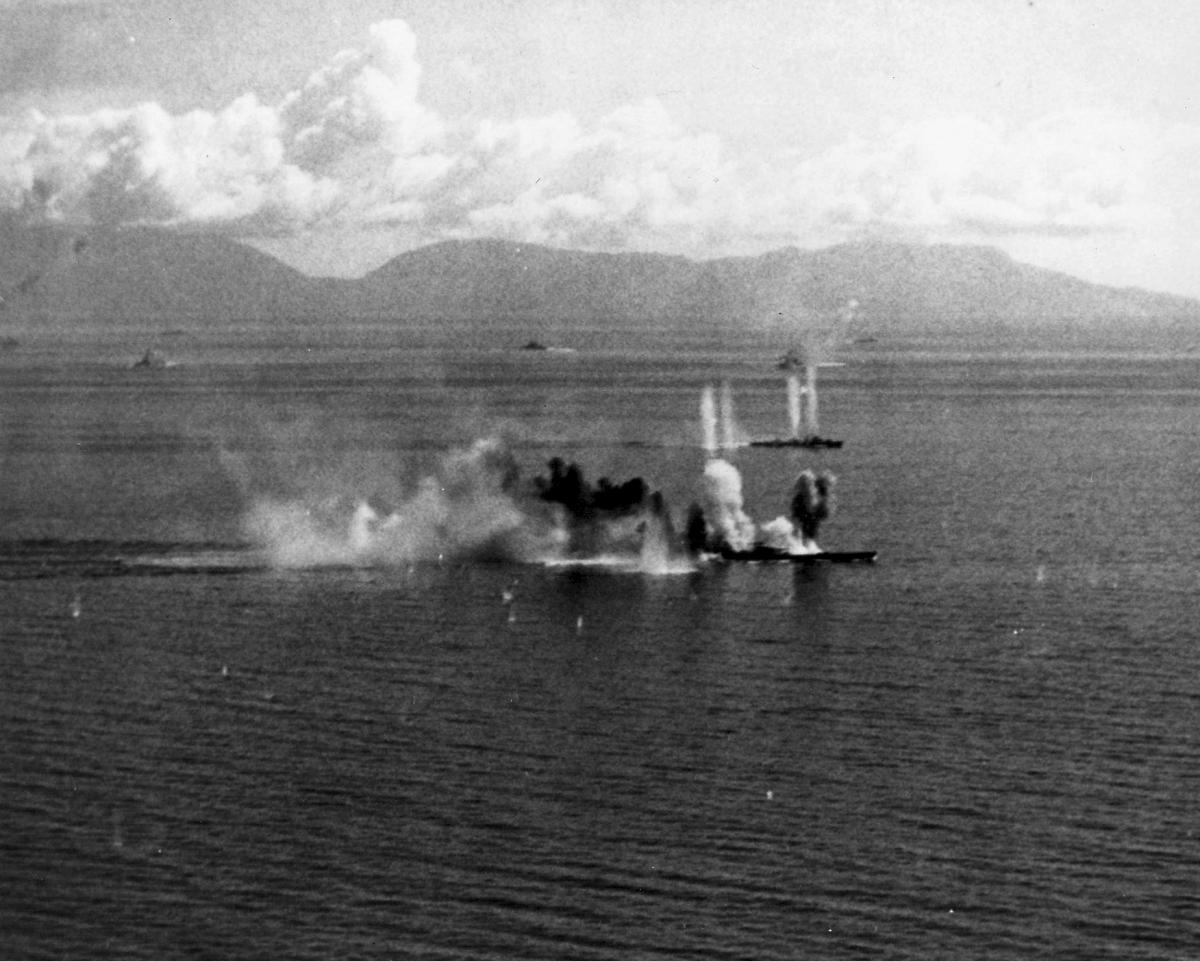

The Kurita force sortied from Brunei on October 22 and was attacked next dawn in Palawan Passage by two submarines, with the result that the cruisers Atago and Maya were sunk and Takao was seriously damaged.

The submarine hazard in Palawan Passage had been expected, and our force was keeping a strict alert and zigzagging at 18 knots. But this submarine attack was a complete surprise, for we had sighted neither torpedo wake nor periscope and had no chance to evade. The main causes of our failure here were that a shortage of fuel restricted our speed and that we had no planes for antisubmarine patrol. All ship-based seaplanes had been transferred to San Jose, Mondoro, because the submarine threat had made it impossible to plan on recovering them. We tended to deprecate American submarines and torpedoes during the early part of the war, but by late 1944 they were our greatest menace, and our anti-submarine measures were totally inadequate.

When flagship Atago was sunk, Kurita's staff transferred to a destroyer. Nine hours passed before we cleared submarine-infested waters and could transfer to Yamato, flagship of the First Battleship Division. During this time Vice Admiral Ugaki in Yamato had assumed temporary command of the entire force.

We had thought from the beginning that a Yamato-class battleship, the most powerful in the world, should have been flagship for the SHO Operation. Combined Fleet, expecting a night action, rejected this idea because the commanding officer should always be in a heavy cruiser, the key ship of night actions. Combined Fleet had never given up this traditional principle of fleet engagements, but the sacrifice of Atago proved them wrong.

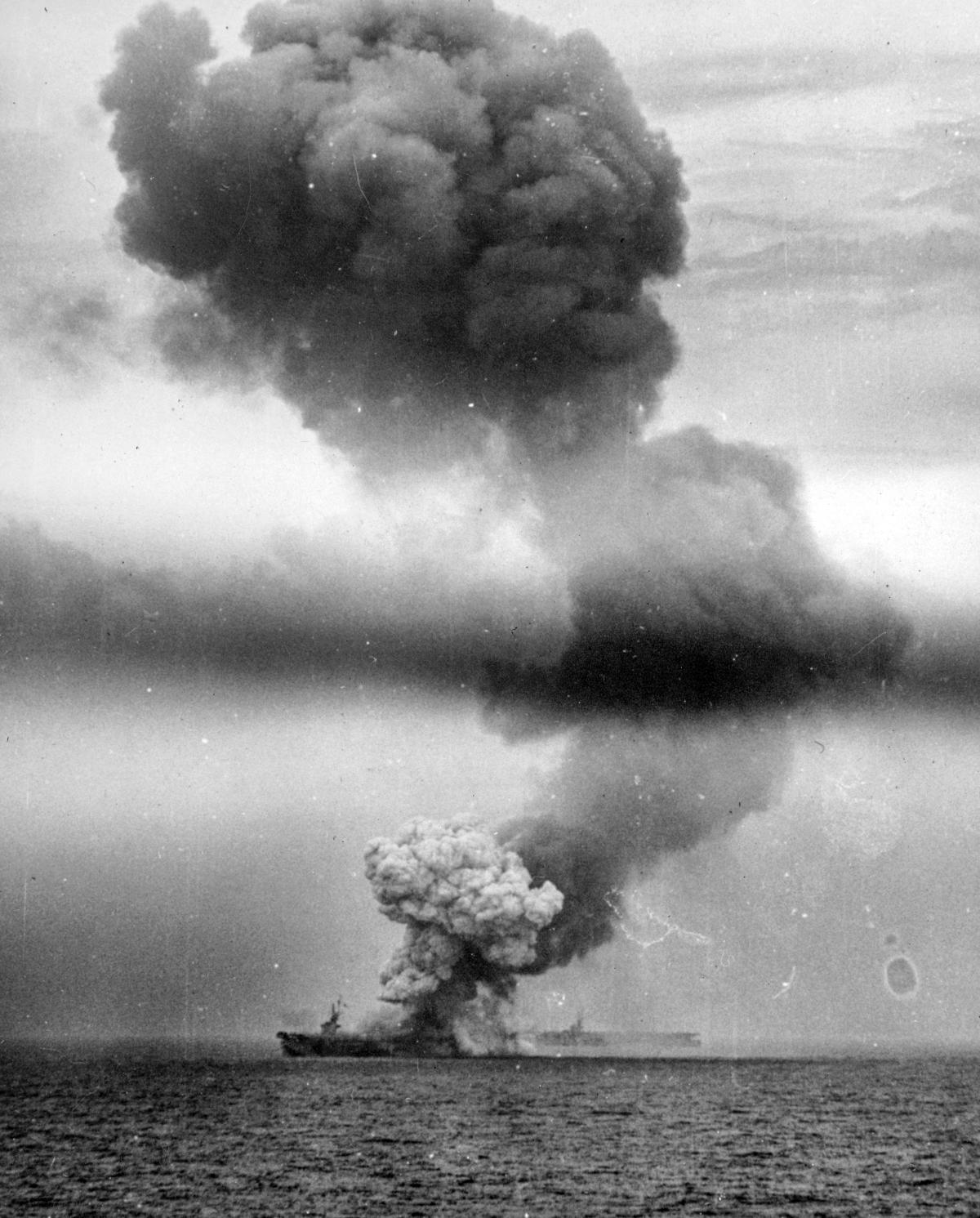

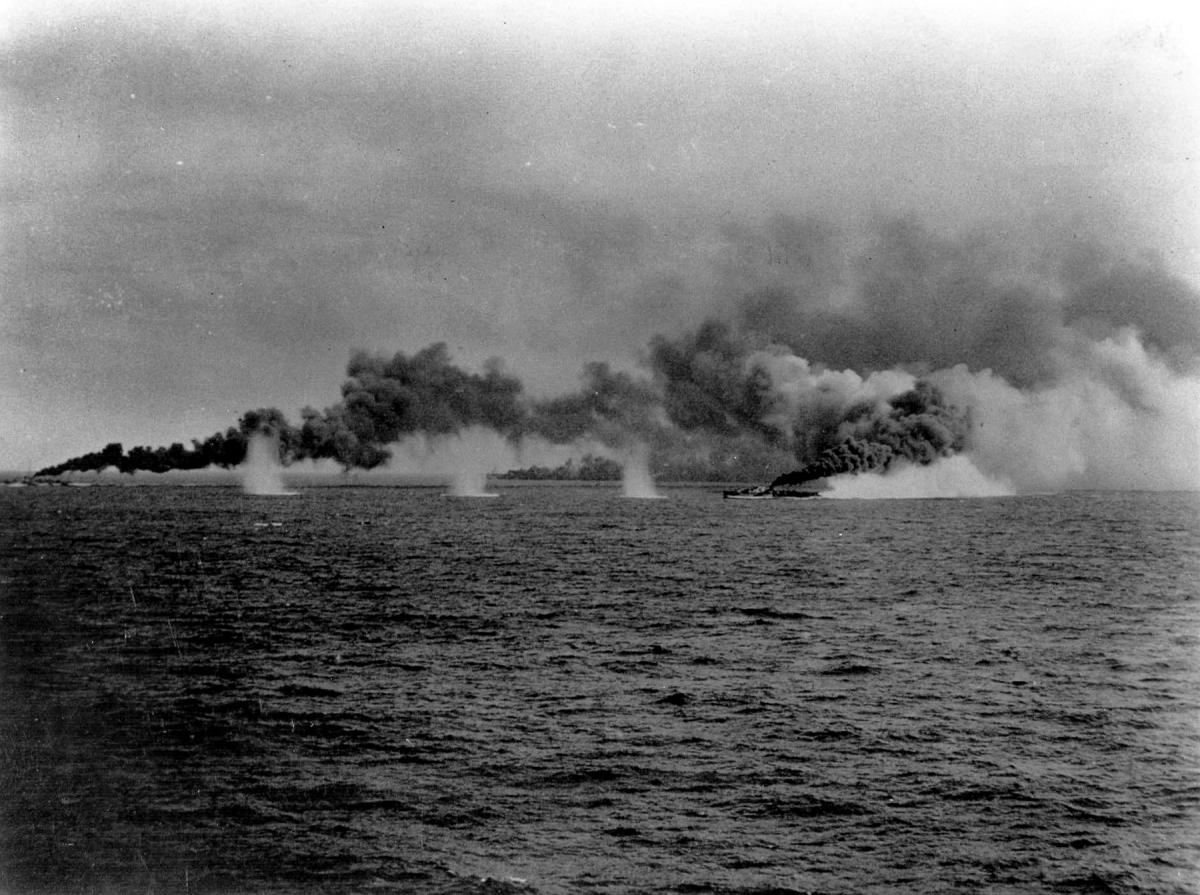

On October 24 Kurita's force in the Sibuyan Sea was the target of fierce raids by carrier-based planes from 1030 until 1530. The Yamato-class battleship Musashi was sunk, a heavy cruiser had to drop out of formation, and other ships were damaged. We had expected air attacks, but this day's were almost enough to discourage us.

Nothing was heard from Ozawa's Mobile Fleet which was supposed to be maneuvering northeast of Luzon. We estimated that the enemy carrier force was just east of Lamon Bay, Luzon, but we had no indication that our air forces had been attacking it. Like a magnet, Kurita's force seemed to be drawing all of the enemy's air attacks, as we approached San Bernardino Strait. If we pushed on into the narrow strait and the air raids continued, our force would be wiped out.

We reversed course at 1530 to remain in the Sibuyan Sea where we could maneuver until our situation improved and at 1600 despatched a summary report to Combined Fleet; it concluded with our opinion that:

Were we to have forced our way through as scheduled under these circumstances, we would merely make of ourselves meat for the enemy, with very little chance of success to us. It was therefore concluded that our best course was to retire temporarily beyond range of hostile planes until friendly planes could strike a decisive blow against the enemy force.

At the same time we sent a message urging land-based air forces to attack the enemy. When, by 1715, the enemy air raids had ceased, we turned east again, without waiting for Combined Fleet's reply, and headed for San Bernardino Strait. We had expected the air attacks to be maintained at least until sundown, but the enemy must have wanted to recover his planes before dark. By continuing aerial contact with us he would have known that our retreat was only temporary. Then the enemy carrier force commander could have ignored Ozawa's Mobile Fleet and concentrated his ships outside San Bernardino Strait to ambush us. If he had done so, a night engagement against our exhausted force would undoubtedly have been disastrous for us.

Thus the enemy missed an opportunity to annihilate the Japanese fleet through his failure to maintain contact in the evening of the 24th. On the Japanese side, of course, Admiral Kurita should have notified Nishimura of our temporary retreat and ordered him to slow his advance. At 1915, a message was received from Commander in Chief Toyoda which read: "With confidence in heavenly guidance, all forces will attack!"

Another message received from his chief of staff said: "Since the start of this operation, all forces have performed in remarkable coordination, but the First Striking Force's change in schedule could mean failure for the whole operation. It is ardently desired that this force continue its action as prearranged."

These messages clarified the decision of Combined Fleet, so we responded: "Braving any loss and damage we may suffer, First Striking Force will break into Leyte Gulf and fight to the last man." And another message was sent to air bases requesting attacks coordinated with the surface fleet.

Six hours behind schedule, we finally passed through San Bernardino Strait at midnight of the 24th, and turned southward, hugging the east coast of Samar and planning to reach Leyte Gulf around 1000.

In the afternoon of the 24th, enemy search planes to the north located Ozawa's ships and judged them to be the main Japanese force, and a threat to the amphibious operation in Leyte Gulf. Erroneously thinking that Kurita had withdrawn in the Sibuyan Sea, the enemy left his position at San Bernardino Strait during the night and proceeded northward to strike Ozawa's fleet, making this the one part of our plan which worked perfectly.

I still cannot understand how the enemy, with his highly developed intelligence system, so badly overestimated Ozawa's force of two old battleships, one regular carrier, three light carriers, three light cruisers, and ten destroyers.

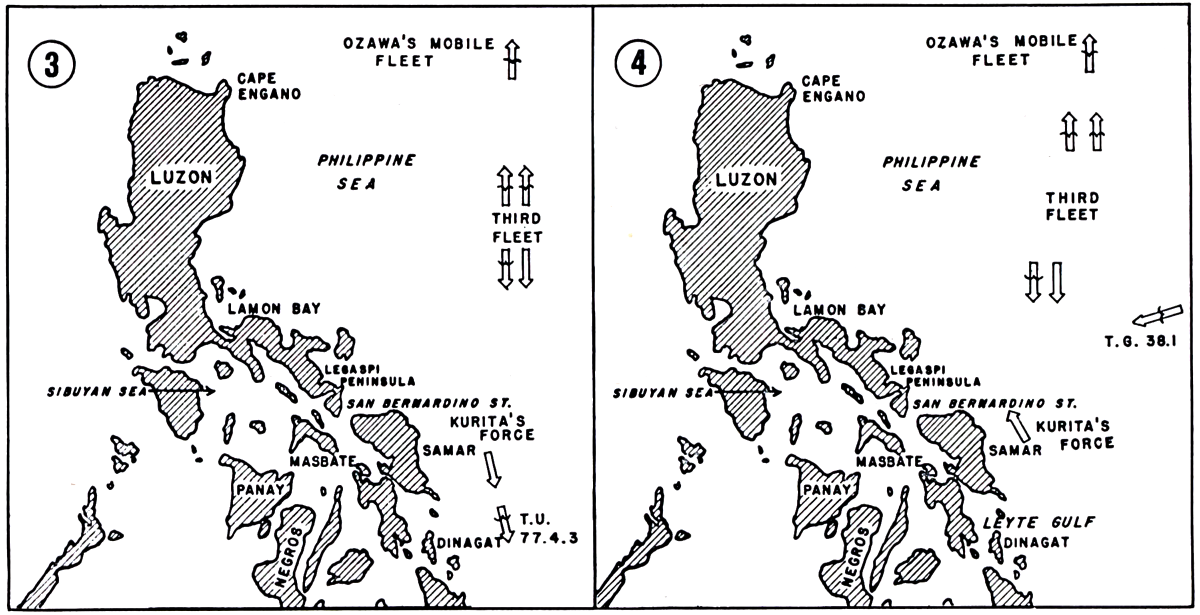

Just as day broke at 0640 on the 25th, and we were changing from night search disposition to anti-aircraft alert cruising disposition (ring formation) enemy carriers were sighted on the horizon. Several masts came in sight about 30 kilometers to the southeast, and presently we could see planes being launched.

This was indeed a miracle. Think of a surface fleet coming up on an enemy carrier group! We moved to take advantage of this heaven-sent opportunity. Yamato increased speed instantly and opened fire at a range of 31 kilometers. The enemy was estimated to be four or five fast carriers guarded by one or two battleships and at least ten heavy cruisers. Nothing is more vulnerable than an aircraft carrier in a surface engagement, so the enemy lost no time in retiring.

In a pursuit the only essential is to close the gap as rapidly as possible and concentrate fire upon the enemy. Admiral Kurita did not therefore adopt the usual deployment procedures but instantly ordered: "General attack." Destroyer squadrons were ordered to follow the main body. The enemy withdrew, first to the east, next to the south, and then to the south west, on an arc-like track In retreat he darted into the cover of local squalls and destroyer smoke screens, while attacking us continuously with destroyer torpedoes and attack planes.

Our fast cruisers, in the van, were followed by the battleships, and little heed was paid to coordination. Because of the enemy's efficient use of squalls and smoke screens for cover, his ships were visible to us in Yamato only at short intervals. The enemy destroyers were multi-funneled, with high freeboard. Their appearance and torpedo firing method convinced us that they were cruisers. We pursued at top speed for over two hours but could not close the gap, in fact it actually appeared to be lengthening. We estimated that the enemy's speed was nearly 30 knots, that his carriers were of the regular large type, that pursuit would be an endless seesaw, and that we would be unable to strike a decisive blow. And running at top speed, we were consuming fuel at an alarming rate. Admiral Kurita accordingly suspended the pursuit at 0910 and ordered all units to close. After the war I was astonished to learn that our quarry had been only six escort carriers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts, and that the maximum speed of these carriers was only 18 knots.

Giving up pursuit when we did amounted to losing a prize already in hand. If we had known the types and number of enemy ships, and their speed, Admiral Kurita would never have suspended the pursuit, and we would have annihilated the enemy. Lacking this vital information, we concluded that the enemy had already made good his escape. In the light of circumstances I still believe that there was no alternative to what we did. Reports from our ships indicated that we had sunk two carriers, two heavy cruisers, and several destroyers. (We learned later that these statistics were exaggerated.) Our only damage was that three heavy cruisers had to drop out of formation.

Our task had been to proceed south, regardless of opposition encountered or damage sustained on the way, and break into Leyte Gulf. But for our unexpected encounter with the enemy carrier group, it would have been simple. We estimated that the enemy carrier task force which was east of San Bernardino Strait on the 24th, had steamed south during the night and taken new dispositions next day, separating into at least three groups so as to surround us; and that we had encountered the southernmost group.

We did not know on the morning of the 25th that Ozawa's Mobile Fleet had succeeded in luring the main enemy carrier task force northward. Admiral Kurita's main force consisted of four battleships, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and seven destroyers. Our only report of enemy-strength (transports and escorts) in Leyte Gulf was from Admiral Nishimura, who had the report of a Mogami seaplane reconnaissance at dawn on the 24th. We had to estimate that there would be a change in the enemy situation as a result of intervening events. We waited eagerly, but in vain, for reconnaissance reports from our shore-based air force.

The enemy situation was confused. Intercepted fragments of plain text radio messages indicated that a hastily constructed air strip on Leyte was ready to launch planes in an attack on us, that Admiral Kinkaid was requesting the early despatch of a powerful striking unit, and that the United States Seventh Fleet was operating nearby. At the same time we heard from Southwest Area Fleet Headquarters that a "U. S. Carrier Striking Task Force was located in position bearing 5° distant 130 miles from Suluan light at 0945." (This report was later found groundless.)

Under these circumstances, it was presumed that if our force did succeed in entering Leyte Gulf, we would find that the transports had already withdrawn under escort of the Seventh Fleet. And even if they still remained, they would have completed unloading in the five days since making port, and any success we might achieve would be very minor at best. On the other hand, if we proceeded into the narrow gulf we would be the target of attacks by the enemy's carrier- and Leyte-based planes. We were prepared to fight to the last man, but we wanted to die gloriously.

We were convinced that several enemy carrier groups were disposed nearby and that we were surrounded. Our shore-based air force had been rather inactive, but now the two Air Fleets would surely fight all-out in coordination with the First Striking Force. If they could only strike a successful blow, we might still achieve a decisive fleet engagement, and even if we were destroyed in such a battle, death would be glorious.

It was these considerations which made us abandon our plan to break into Leyte Gulf. We proceeded north ward in search of the enemy carrier groups.

Looking back today, when all events have been made clear, we should have continued to Leyte Gulf. And even under the circumstances and with our estimate of the enemy situation at that time, we should have gone into the gulf.

Kurita and his staff had intended to take the enemy task force as the primary objective if a choice of targets developed. Naturally, our encounter with the enemy off Leyte on the 25th was judged to be the occasion for such choice.

On the other hand, there was considerable risk in changing our primary objective when we did not know the location of the other enemy task forces or how effective our land-based air forces would be. We should have chosen the single, definite objective, stuck to it, and pushed on. Leyte Gulf lay close at hand and could not run away.

Enemy air raids of October 24th had been fierce, and next morning three of our heavy cruisers were damaged by air attacks. That afternoon we were pounded by carrier planes with no fatal damage, but near-misses caused most of our ships to trail oil. On the morning of the third day, we were again attacked from the air, and light cruiser Noshiro was sunk. Around 1100, flagship Yamato was the target of about thirty B-24's. The flagship suffered no direct bomb hits, but near-misses around her bow raised gigantic columns of water. In this raid I was wounded in the waist by splinters from a bomb blast.

In three consecutive days the enemy sent some 1,000 aerial sorties against us . Never was a fleet so heavily pounded by air attack.

To a surface fleet there is no engagement so disadvantageous and ineffective as an antiaircraft action. It does not pay off. We had no air cover to repel the enemy, for whom it was a pure offensive.

Yamato, being the largest ship and flying an admiral's flag, was a constant target of attack. It was only through the maneuvering skill of her captain that she came out of the action virtually unscathed.

During these three long days of one-sided air poundings, our consorts were being sunk or damaged all around, but the men never faltered. They remained full of fighting spirit and did their very best. Their gallant attitude made them worthy of praise as the last elite of the Japanese Combined Fleet.

The enemy's high-speed battleships and carriers had headed south again upon learning that the situation at Leyte had become serious and that Ozawa had suddenly turned northward in the morning of the 25th. If the enemy carrier task force had seen that Ozawa's fleet was merely a decoy and had started south a few hours earlier, it could have caught Kurita.

In fact, after suspending our south ward drive in pursuit of the enemy off Samar Island on the morning of the 25th, we fully expected to encounter the Americans before we could reach San Bernardino Strait. We were still ready for a last decisive battle under any condition.

Early in the morning of the 24th, the Americans had sighted Kurita's main force in the Sibuyan Sea as well as the Nishimura detachment to the south of Los Negros Island. Both forces could have been tracked thereafter to show our movements and destination. We had anticipated that, and we expected the Americans to take every measure to intercept us.

Our most serious problem on the 24th was getting through and out of San Bernardino Strait. Just the navigation of the strait was difficult enough with its eight-knot current, and transiting it by day with a single ship required considerable skill; one can imagine the increased difficulty of doing it with a large formation of ships at night.

In the strait we had to maneuver in a single column which extended over ten miles; once through, our formation had to be changed to a night-search disposition which spread over a score of miles. At the time of shifting formation our force was extremely vulnerable to attack.

We anticipated enemy submarines at the exit of the strait to intercept us, and a concentration of surface craft to force a night engagement upon us. We were, therefore, greatly surprised when neither of these situations materialized.

We passed through the strait safely and headed southward, sure that the Americans were well aware of our movements. We also thought that the enemy's excellent radar must be tracking our force and plotting its every move. Thus we certainly never expected to encounter enemy carriers as we did so suddenly at daybreak of the 25th. I still wonder why those carriers came so unguardedly within range of our ships' gunfire.

On land or sea, retirement is the most difficult of all tactics to execute successfully. But the retiring tactics of the American carriers in the battle off Samar in the morning of the 25th were valiant and skillful. The enemy destroyers coordinated perfectly to cover the low speed of the escort carriers, bravely launched torpedoes to intercept us, and embarrassed us with their dense smoke screens. Several of them closed our force at 0750 and launched some ten torpedoes. Battleships Yamato and Nagato sighted them in time to evade but had to comb their tracks for five miles or more before resuming pursuit of the enemy.

The escort carriers maneuvered in tight combination. They made good their escape on interior lines, causing us to think that they were regular high-speed carriers. I must admit admiration for the skill of their commanders.

On October 26th, the air raids against Kurita's force ended around 1100. As on the day before, we expected to be attacked all day long. We had not the least expectation that the enemy would suspend his raids an hour before noon. Perhaps it was because we had pulled out of combat range of the enemy carrier task force.

Our greatest concern was that the enemy, following up his successes, might pursue us westward through San Bernardino Strait, into the Sibuyan or Sulu Seas, and launch annihilating air strikes. If this threat had materialized, the American victory would have been complete.

Some may say that this would have been risky for the Americans. But what Japanese strength could have opposed United States carriers in pursuit of Kurita's retreating force?

Our shore-based air force, judging from its inactivity, must have been pretty well knocked out, and Ozawa's battered fleet had been almost destroyed. We might have inflicted some damage: but there was no Japanese force strong enough to give serious opposition.

American reluctance to give all-out pursuit is perhaps justified by some strategic concept which advocates prudence and step-by-step procedure; but from the Japanese point of view, the Americans gave up pursuit all too soon and missed chances of inflicting much greater losses upon us.

Analyzing the whole course of events of this battle, we see that chance played a definite role in each part of the action and thus influenced the whole.

As in all things, so in the field of battle, none can tell when or where the breaks will come. Thus events and their consequences are often determined by some hair-breadth chance in which the human factor has no control at all. Chance can make the victor of one moment into the vanquished of the next.

The Japanese Navy's total of combatant vessels in this great battle theater was: nine battleships, four aircraft carriers, thirteen heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, and thirty-one destroyers. Of these we lost three battleships, all four carriers, six heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and seven destroyers. These losses, most of which were caused by air attacks, spelled the collapse of our Navy as an effective fighting machine.

I would hardly say, however, that our losses were greater than we anticipated. Nor do I feel either that the Japanese lost because their strategy and tactics were wrong, or that the Americans won because their strategy and tactics were particularly good.

The physical fighting strengths of both parties were too greatly divergent. On logical analysis, the SHO Operation plan formulated by Combined Fleet Headquarters was unreasonable. Both carrier and land-based air forces had been weakened to a point where they could not be effectively coordinated with the surface fleet, which was thus subjected to concentrated enemy attack without any air protection.

In modern sea warfare, the main striking force should be a carrier group, with other warships as auxiliaries. Only when the carrier force has collapsed, should the surface ships become the main striking force. However majestic a fleet may look, without a carrier force it is no more than a fleet of tin.

A decisive fleet engagement determines conclusively which contending party shall have sea and air supremacy. By October, 1944, the Japanese fleet no longer actually had strength enough to carry on a decisive engagement. Its strength and ability had been so reduced that it had to resort to the makeshift plan of attacking transports. Just think of sending a great mass of surface craft, without air cover, nearly 1000 miles, exposed to enemy submarines and air forces, with a mission of breaking into a hostile anchorage to engage. This was a completely desperate, reckless, and unprecedented plan which ignored the basic concepts of war. I still cannot but interpret it as a suicide order for Kurita's fleet.

When Kurita suspended chase of the escort carriers off Samar on the 25th, we had four battleships, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and seven destroyers. Let us suppose that he had continued south, broken into Leyte Gulf as scheduled, destroyed all the transports and their escorts, and succeeded in withdrawing unscathed. Our initial operational objective would have been attained, but two facts remained. First, it was five days since the enemy convoy had started unloading. Hence, the transports would have discharged most of their cargo, making them practically worthless as strategic targets. Secondly, the convoy escorts were old ships and their destruction would have impaired but slightly the overall fighting efficiency of the enemy. If any of our ships had actually remained afloat after such an attack, they would still have been without carrier support, a tin fleet, existing only to be destroyed by the enemy. Their existence or non-existence could not have affected the tide of war, and Japan was waning toward her final defeat. It is clear that our SHO Operation could not have influenced the outcome of the war.

During the Pacific War there were two decisive naval battles in which the whole outcome of the war hung in the balance. First was the Battle of Midway in early June, 1942. At that time the fighting power of the Japanese Navy was at its zenith, and everyone in Combined Fleet was firmly convinced of victory. But our defeat in the carrier duel at the outset of the battle cancelled our hope for a decisive engagement and we had to withdraw.

The second was in mid-June, 1944, the Battle of the Philippine Sea. There were many defects still to be remedied in our carrier striking force, but Combined Fleet was able to engage in battle with a fair degree of self-confidence. Once again we suffered an aerial defeat in the opening phase of the battle which drove us to a general retreat.

Until the Battle for Leyte, our battleship force was relatively immune from loss or damage and did maintain its fighting efficiency. To the uninitiated these ships must have appeared as great floating forts, and as the key by which Japan might recover from her hopeless situation. But a fleet of super-dreadnaughts alone, however powerful their guns, could no longer qualify as the main striking force in a decisive fleet engagement.

I have nothing but respect and praise for the excellence of weapons, thoroughness of training, tactical skill, and bravery of the enemy in this battle.

There is an old maxim: "Battle is a series of blunders and errors. The side which makes the least will win and the side which makes the most will lose."

The truth of this maxim was never more apparent than in the Battle for Leyte Gulf. Anyone who has experienced combat knows that errors in judgment made under fire are not always culpable. The ever-changing tide of battle subjects us to Fate and Chance, which are beyond our control.

Captain Toshikazu Ohmae has been kind enough to translate my essay on the Battle for Leyte Gulf. After completing the task, he asked me two questions concerning the action which, because they may also occur to American readers of this article, I have tried to answer as fully as possible. The questions and my answers, which have been reviewed and approved by Admiral Kurita, follow:

(Q.) You (Vice Admiral Koyanagi) believe that the First Striking Force should have been committed to decisive battle with the enemy task force and should not have been expended on the enemy convoy. How did you estimate that the First Striking Force might have deployed to encounter and destroy the enemy task force?

(A). It was obvious that without air support we had no chance of defeating the elite enemy task force of crack battleships and high-speed regular aircraft carriers. It was indispensable that we have the cooperation of friendly air forces. Analyzing Japanese air strength, however, we could see that with Ozawa's Mobile Fleet still recovering from its losses in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, there remained only our land-based air forces—the First and Second Air Fleets.

As it turned out, these two air fleets achieved practically nothing during the battle, whereas in planning the SHO Operation we had counted heavily on them. They should have conducted all-out attacks on the enemy fleet to support our surface force in this battle. If they had damaged enemy battleships and carriers, the First Striking Force could have carried out a decisive sea engagement.

We knew full well that the combat effectiveness of our air force was limited and should not be over-estimated. It was the surface fleet that would have to bear the brunt of battle.

Despite all this we were of the opinion that the First Striking Force should be committed to the destruction of the enemy task force, his strongest fighting unit, because this would be our last chance against it. This was the desire of all our senior officers and we were happy with our assignment.

(Q). You have said that the message giving the position of the enemy task force at 0945 was one of the main reasons for suspending our penetration into Leyte Gulf. This dispatch is not recorded in any document, but granting its existence, it pertained to the enemy task force approximately three hours before, and nothing had been reported since. Hence our chances of catching this enemy were slim, while the stationary ships in Leyte Gulf could be hit with almost 100 percent certainty.

I assume then that the First Striking Force gave up entering the gulf to seek the new enemy task force because of its belief that it should have been committed to the destruction of the task force in the first place. But the target of your attack was changed three times. Pursuit of the escort carrier group was abandoned after two hours' chase, and forces were concentrated for breaking into Leyte Gulf, but this objective was soon given up, and you proceeded northward in search of the newly reported task force. What caused you to change target so often, and how did you plan to contact this enemy to the north?

(A). Though I have already written about giving up the pursuit of the enemy escort carriers in the morning of the 25th, I can easily imagine that everybody wonders why we did not continue the pursuit of the vulnerable escort carriers and attempt their complete annihilation.

But as a matter of fact, we had concluded that these were regular carriers. (It was only after the surrender that I learned it was an escort carrier group, when I was interrogated by members of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey in Tokyo.)

We judged that the enemy carrier group was steaming at a speed equal to or greater than ours because we did not close the distance to the enemy in two hours' pursuit. We could not observe the enemy situation because of local squalls and enemy smoke screens. Our intra-fleet communication was so congested that we received no information of the enemy from our van cruisers, and we concluded that the cruisers had also lost contact with the enemy.

Another factor was that we could not be indifferent toward our fuel situation. Endless pursuit would mean fruitless consumption of valuable fuel, and the consumption of fuel in two hours' top speed pursuits could not be overlooked Our decision was to give up pursuit of the enemy carrier group.

The reason we then chose a northerly heading was that we wanted to separate from the enemy as much as possible. Critics may say that a southwesterly course would have quickened our regrouping, but there were local squalls to the southwest, and remnants of the enemy smoke screen still limited visibility. Moreover we had to consider the offensive possibilities of the group we had just been chasing. Proceeding southward, we would be exposed to possible counterattacks by the enemy task group which was thought to include high-speed battleships and large cruisers.

It was 1100 before we had regrouped, and by then not an enemy ship was in sight. The enemy force being driven away, we determined to return to the initial strategical objective, the breaking into Leyte Gulf, the operation set forth by the Commander in Chief, Combined Fleet, and we accordingly changed our course toward the Gulf.

Since our surprise encounter with the enemy task group early that morning, we had been so busily engaged in combat that there had been no time for cool analysis. Now that we were not engaged, the staff met for discussions of our next move. Ali available information was gathered and analyzed. It was concluded that the First Striking Force should give up the scheduled plan of breaking into Leyte Gulf and try for decisive battle with the enemy task force in the open sea. Admiral Kurita gave his consent to this new plan. The circumstances which led to this decision have been noted in my essay in detail.

It was certainly not a powerful enemy force in Leyte Gulf which repelled us from the Gulf. In fact we believed the force in Leyte Gulf to be rather weak. We seem to have been obsessed with the idea of the task force being our most important target.

After the war Admiral Kurita recalled:

"My force was attacked by an enemy bomber group which disrupted our formation as each ship evaded independently. I do not remember the exact time of that attack but it was just after we altered course toward Leyte Gulf. It was at a point where many men from a sunken enemy carrier were floating. Unlike the sporadic attacks we had experienced that morning, this bombing was of a far larger scale and appeared to be more systematic. I concluded that fresh enemy carrier task groups had commenced all-out attacks upon us. Shortly before that we had known through enemy radio interception that the force in Leyte Gulf was requesting reinforcements and that It would be two hours before they could reach Leyte Gulf. From Manila had come a message giving us the 0945 position of an enemy task force. On the basis of these pieces of information we concluded that the powerful enemy task force was approaching. As it would be disadvantageous for us to be subjected to severe air raids in narrow Leyte Gulf, I thought we should seek battle in the open sea, if possible, where maneuvering room would be unlimited. The systematic air raid came just after I had reached this decision, so I immediately consented to the suggestion of my staff that we should seek the enemy task force instead of going after the ships in Leyte Gulf. "

We had estimated that the enemy would not be far away, but we had not been able to confirm his exact position. We had no search planes, but we still believed that the Philippines-based air forces would conduct all-out attacks in the afternoon, delivering a serious blow to the enemy task force and revealing its position to us. We would then have a chance for a decisive sea engagement either by day or night.

We anticipated no difficulty in making contact with the enemy task force, because we estimated that the enemy with ail his power was already pursuing Kurita's force and would contact and challenge us by sunset at the latest.*

* Translated by Captain Toshikazu Ohmae, former Imperial Japanese Navy, and edited by Mr. Roger Pineau.

* Editor's Note: The reader should observe that Admiral Koyanagi's account of what happened in the Japanese Second Fleet on the morning of October 25, 1944, off Samar is more coherent than that to be found in interviews with Japanese naval leaders immediately after the war. Battle fatigue, poor communications, and a total lack of air reconnaissance influenced the Japanese decisions. In the eight years that have passed since the Battle for Leyte Gulf, it is inevitable that a certain amount of rationalizing should creep into most accounts of the battle.