Prior to the introduction of steam power in the 19th century, warships were dependent on the wind and their sails to provide both motive power and the ability to maneuver in battle. Sails were complex objects constructed with considerable skill. To function well, a sail needed to be strong enough to withstand the power of wind and battle damage but also light and flexible enough to be handled by sailors working aloft, often in challenging conditions. This balance was hard to achieve because the stronger the type of material used, the heavier and more rigid the sail became. The solution was to use varying grades of canvas in the different parts of the sail, with lighter material in the center, and heavier canvas toward the leech (side edges), where the most strain would occur.

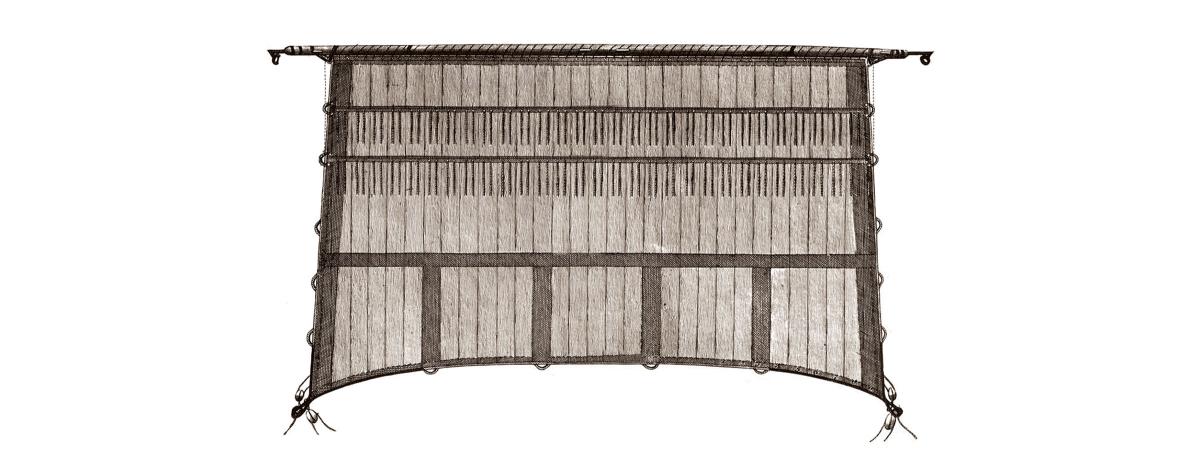

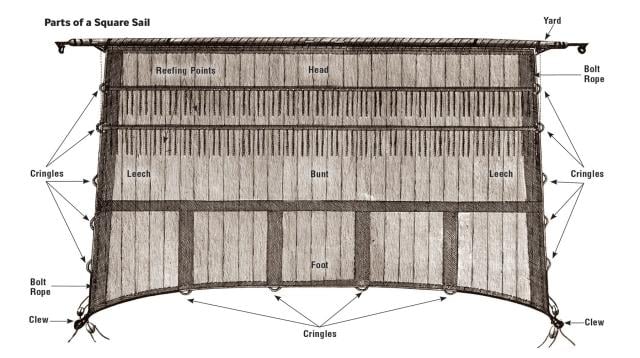

Even a square sail had a sophisticated design. For a start, it was not really square. It generally had a head (top) of a width to match the yard it was attached to, and a wider foot (bottom) in proportion with the longer yard below. The foot itself was not straight, but curved in a gentle arc, so as to keep the canvas free of rigging. Then the middle of the sail, called the bunt, was cut with extra material so that it would form a belly in which to catch the wind.

At the edges of a sail, the canvas was doubled over to increase its strength and then a bolt rope was stitched to the edge to prevent it from splitting. This rope was offset, so that even on the blackest night a sailor could distinguish front of sail from back by touch alone. The sail then needed to have various cringles (holes), clews (reinforced points for attaching lines at the lower corners), and reefing points (short lengths of rope for reducing sail) added. To make a single topsail for a ship-of-the-line has been estimated to have taken more than a thousand man-hours.

The 18th century saw considerable change in the strategic role of the warship. Prior to 1700, major naval powers fought their fleet actions in European waters, during the summer months, and never far from a friendly port. Firepower was everything, and ships were loaded with as much ordnance as possible, to the detriment of their handling and weatherlyness. But the rapidly growing colonial economies in the New World and a massive expansion in trade with Asia led to a change in strategic priorities. Naval power needed to be projected across the oceans of the world using ships capable of operating in more demanding weather. Naval actions also changed, with greater emphasis on maneuvering a fleet to gain a tactical advantage over an opponent. As a result, warships and their sails needed to adapt to these requirements.

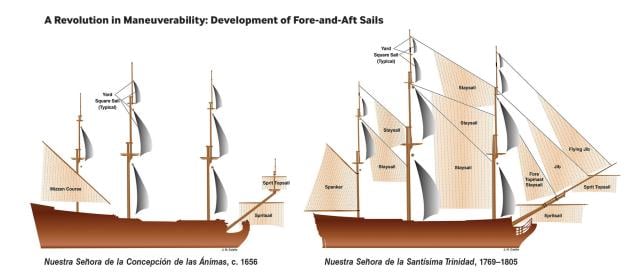

One such change was an increase in the use of fore-and-aft sails, that is, ones aligned with the centerline of the ship. They allowed a ship to sail closer to the wind, conferring both tactical benefits in action and greater safety in poor weather, particularly when on a lee shore. Stay sails—ones that are set between the masts—were first introduced in the Royal Navy in 1709. Initially they were triangular, but after 1760, once their utility was proved, they were replaced by larger quadrangular shaped ones. By the Napoleonic period, warships battling each other to gain the weather gauge would frequently use fore-and-aft sails alone.

The most effective sails for maneuvering a large warship were those at the bow, and these underwent the most profound changes. The farther forward such sails are deployed, the greater the leverage they will exert, increasing the speed at which a ship will be able to turn, particularly through the wind. At the start of the period, warships had a small vertical mast stepped on the end of a short bowsprit with one or occasionally two square sails—called a sprit topsail and sprit topgallant sail—set on it. These, together with a larger square spritsail suspended below the bowsprit, provided the turning leverage. It was a rather complicated rig of limited effectiveness, that began to be replaced in smaller warships from 1705 onward.

The little spritsail mast was removed and replaced by a long extension of the bowsprit called a jibboom from which a number of large triangular fore-and-aft sails could be set. Within two decades, all warships had adopted this improved rig. It transformed maneuverability, both doubling the area of canvas that could be set in this critical area and moving the sails even farther forward to maximize their effect.

Of all the major sails on warships, the mizzen course (the lowest sail on the mast aft or next aft of the mainmast) changed the most. The advantages to maneuverability of having a large fore-and-aft sail at the stern was well established, and this had been provided by adopting a lateen sail from the Arab world. It supplied considerable leverage when turning but was awkward to handle. Also, when the lateen yard was swung in one direction, the small triangle of canvas in front of the mizzenmast moved to the opposite side, partly counteracting the effect. From the 1730s onward, initially in British and Dutch warships, the front part of the lateen sail was removed and the new fore edge was laced to the mizzenmast. It was a change that was soon adopted by most navies, although this still left the ship with the bare front half of the mizzen yard.

During the American Revolution, the British began to replace the lateen mizzen course with a new, larger gaff and boom sail called a spanker, and this was gradually taken up by all warships, although even in the Royal Navy it was not fully adopted for some years. At the 1798 Battle of the Nile, Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson’s flagship, HMS Vanguard, carried a mizzen yard—the only ship on either side that still had one. Spankers were much handier and more effective than the sails they replaced. It is worth noting that the Vanguard alone among Nelson’s ships was rolled onto her beam ends and partially dismasted in a gale during the Nile campaign. She had to be towed to safety by another ship of the line, HMS Alexander, which had survived the same summer storm. The Alexander was fitted with the newer spanker rig.

In an era when a warship’s firepower could only really be used to the sides, the ability to outmaneuver an opponent in action could confer a huge advantage. By the end of the 18th century, thanks to the cumulative innovations to the sails and rigging of their vessels, commanders were able to contemplate actions that would have been regarded as suicidal earlier in the century. One such action occurred on the night of 30th March 1800. The 36-gun frigate HMS Penelope, under the command of Captain Henry Blackwood, intercepted the much more powerful 80-gun Guillaume Tell, which had broken out from Malta. The French ship-of-the-line was being pursued by a Royal Navy squadron, which she was comfortably outsailing.

The Penelope closed with her from astern and proceeded to spend the night out-maneuvering her clumsier opponent. Through a combination of superb seamanship and exploiting the greater agility of his ship, Blackwood repeatedly crossed the Frenchman’s stern, raking her each time and then swiftly turning away before the Guillaume Tell could bring her broadsides to bear.

By dawn the French ship had been so badly damaged that she was soon overhauled by her pursuers. By contrast, HMS Penelope was virtually unharmed, suffering only one dead and three injured in the action. It was a result that would have been impossible without the substantial changes made to the sails and rig of 18th-century warships.