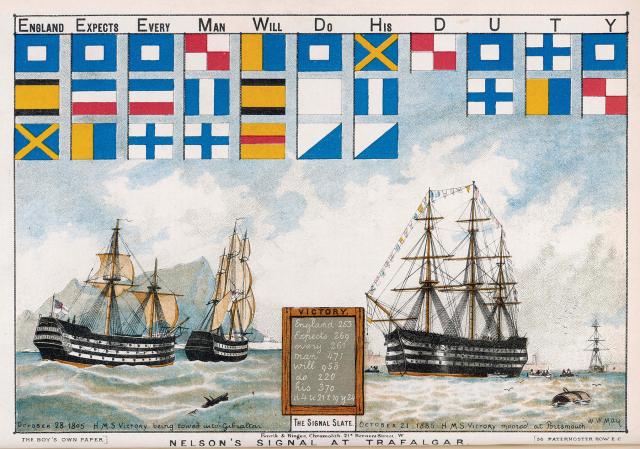

As the sun rose on 21 October 1805, the most famous naval battle of the Age of Sail was about to begin off the southwest coast of Spain. On board HMS Victory, Vice Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson was busy signaling his fleet as it bore down on its Franco-Spanish opponents. The morning wind was light, making the British approach slow, if relentless. This gave the admiral plenty of time to complete his dispositions. Shortly before noon, when all was in place, sailors on board the Victory hauled aloft 31 colored flags, making Nelson’s signal: “England expects that every man will do his duty.” It was then replaced with “Engage the enemy more closely,” which remained flying throughout the Battle of Trafalgar, even after its author had died.

Often overlooked in accounts of Nelson’s famous signal was its novelty. Nelson was the first admiral able to send a message to his command in battle that was more than just a functional order. Only two years prior, Royal Navy Captain Home Riggs Popham had devised the particular signaling system Nelson used. It was the latest solution to the vexed issue of command and control in the Age of Sail. A general on land had a variety of options, from drums or bugles for simple commands, to dispatching a horseman with a more complex message. He could even ride over himself to deliver detailed instructions, but none of these options were available to a commander at sea.

The first attempts to solve the problem came in the 16th century, almost as soon as specialized sailing warships appeared. Flags and banners already distinguished friend from foe and identified an admiral’s flagship (hence the name), and some were used for limited signaling. Unfortunately, the paucity of available flags meant that little more than a few simple instructions, arranged in advance, could be sent. For any more complex tactical orders, signaling systems tried to replicate the direct contact available to a general. For his 1617 expedition to Guiana, Sir Walter Raleigh’s instructions to his captains included the prearranged signal: “When the Admirall shall hang out a flagg in the main shrowdes, you shall knowe it to be a flagg of counsell; then come aboard him.”

During the 17th century, naval warfare became increasingly important. The colonization of the New World and the discovery of sea routes to Asia meant the major European powers now had lucrative maritime commerce to protect. As the century progressed, the fleets of warships grew ever larger. The Four Days’ Battle (see “Four Days in 1666,” June 2021, p. 8) saw 79 English warships pitted against a Dutch fleet of 84.

Engagements on this scale were often little more than confusing melees, prompting admirals in many navies to realize that a better organized fleet should be able to gain a clear advantage. Commanders began to organize squadrons into lines of battle with uninterrupted fields of fire, but maneuvering them required a communication system that was more than a few ad hoc signals.

General-at-Sea George Monck, commander of the English side during the Four Days’ Battle, was one of three admirals who devised the first formal signaling system issued to the fleet. The 1653 Instructions for the Better Ordering of the Fleet in Fighting (also known as The Fighting Instructions) introduced a system that used three flags and a pennant. Depending on where in the rigging they were hung, each could mean a different order. Admiral Lord Edward Russell expanded on this with five additional colored flags in his 1691 Permanent Instructions. When combined with signal guns, the number of possible maneuver signals grew to 22.

Russell’s system remained in use for much of the first part of the 18th century, despite its many limitations. Quite naturally, the small number of available signals was devoted mainly to maneuvering the fleet, leaving few for routine administrative orders. It also left little scope for more complex messages. A scouting warship could signal that the enemy was in sight, for example, but had no options to report the size of the threat or its motions. Furthermore, Russell’s signals could quickly break down in action. Because the system depended on where a flag was hung, it could fail if the flagship lost any masts. And some were problematic at any time: It is hard to see how the signal for “break off the action” in one later version—a flag accompanied by a gun fired to leeward—would ever have been noticed in the heat of battle.

For much of the 18th century, successive evolutions introduced additional orders, adding more and more flags, until, by the time of the American Revolution, the Royal Navy used 40 different flags and 7 pennants in various combinations. The system had become overly complex, with many flags too alike. Simultaneously, commanders such as Admiral Lord Richard Howe and Admiral Sir George Rodney were revolutionizing fleet tactics, which in turn produced a requirement for more complex signaling options. Clearly, a radical rethink of naval communications was required.

Howe, in particular, was a keen supporter of innovation in this area and encouraged several signal reformers in the service. Their work paralleled similar development in the French and Spanish navies. The breakthrough was made in 1782 when Lieutenant Charles Knowles produced a simplified system that included a set of ten flags, each representing a single digit. He originally intended for them to be used in pairs, producing 99 numbered signals that an admiral could use for predetermined orders. Subsequent reformers seized on this idea, expanding the number of possible signals first by using groups of three flags, and then four.

In 1790, Admiral Howe issued the first operational codebook for his captains in which flags represented numbers, instead of direct commands. This greatly increased the volume of orders that could be transmitted, and Howe’s system was adopted by the Royal Navy and used for the war that followed the French Revolution. His system probably would have still been in service at Trafalgar had the code book behind it not fallen into enemy hands in 1803. It was replaced by Popham’s somewhat richer system, with its wealth of additional words and phrases, allowing Nelson to send his famous signal.

The beauty of Knowles’ and Popham’s systems was their fundamental simplicity. They required only the ten numeric flags, plus a few additional ones to qualify a signal, such as a preparative flag and a “signal ends” one. Popham’s signal book had a dictionary of more than a thousand words, each with a four-digit code, plus a similar number of sentences and orders, as well as the ability to spell any word that had been left out. If one ship wanted to tell another “I am not acquainted with that harbor,” for example, this could be done with the code 2349.

The system was good, but not perfect. Nelson actually wanted his Trafalgar signal to begin “England confides” (i.e., “has confidence”). Unfortunately, “confides” was not in the codebook, so to avoid spelling it out, the more hectoring “expects” was chosen instead.

With a few exceptions, most large 18th-century naval battles prior to 1790 were indecisive affairs, often with two lines of warships bombarding each other from distance. Only after Howe’s signaling reforms did the annihilating Royal Navy victories associated with the Age of Nelson begin to take place. Much of the credit for this must go to Nelson, St. Vincent, and the other victorious commanders, of course. But it is also important to look at the command-and-control tools available to them. Nelson could transmit almost any signal he chose, a freedom of communication that was denied to admirals of earlier ages. What might his predecessors have achieved had they, too, been sent into battle with Popham’s signal book?