Great Britain’s Royal Navy has been most innovative in carrier aviation—building the world’s first full-deck aircraft carrier and developing the angled flight deck, mirror landing system, steam catapult, and even a rubber flight deck.

After World War II, the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough, England, led the search for effective methods of operating jet-powered aircraft from carriers. Even before the war ended, that research and test organization had begun to consider the elimination of wheels from jet aircraft. Unlike piston-engine aircraft with their large, whirling propellers, jet aircraft theoretically could land on their fuselage bottoms. Eliminating landing gear and related machinery and structures would permit an aircraft weight reduction that could enable better aerodynamic performance or increased armament. Further, without the need to retract the undercarriage, wings could be made thinner, resulting in further improvements to the aircraft’s characteristics.

At a January 1945 RAE conference, participants discussed several methods of landing and launching aircraft without wheels. Suggestions included operating the aircraft from soft ground or sand, a sprung deck, flexible material floating on water, a wire net, a trolley running along tracks, and wires stretched between towers on a ship (a variation of the U.S. Navy Brodie system used on tank landing ships in World War II).

Major F. M. Green, a leading aeronautical engineer formerly with the Royal Flying Corps, proposed landing a wheelless jet aircraft on a flexible “carpet” suspended by shock absorbers. Such a runway, coupled with the use of conventional arresting wires, could halt the aircraft with a minimum of runout after touchdown. A carpet 150 feet long and 40 feet wide was proposed for a jet aircraft of about 8,000 pounds. Wear on the rubber surface would be extremely small, especially if the surface were kept wet. Subsequent work on the “undercarriage-less aircraft” project was slow because the RAE was engrossed in testing advanced Allied aircraft and then seeking out and evaluating surrendered German aircraft. The flexible deck system was not ready for testing until late 1947.

Just after noon on 29 December 1947, Lieutenant Commander (later Captain) Eric M. Brown, a veteran carrier pilot, approached a flexible-deck runway at Farnborough in a Sea Vampire fighter with the wheels retracted. As the twin-boom aircraft approached the carpet area, the plane sank faster than had been anticipated, and Brown increased power to check the plane’s downward motion. But because of the slow acceleration response to the throttle (common in early jets), the aircraft kept sinking and struck the ramp at the end of the carpet. The arresting hook bounced up and locked, and the plane’s tail booms were damaged, locking the control surfaces. The Sea Vampire bounced twice along the carpet, reached the end, and then struck the ground, badly damaged. Brown was uninjured, but it was an unpromising start.

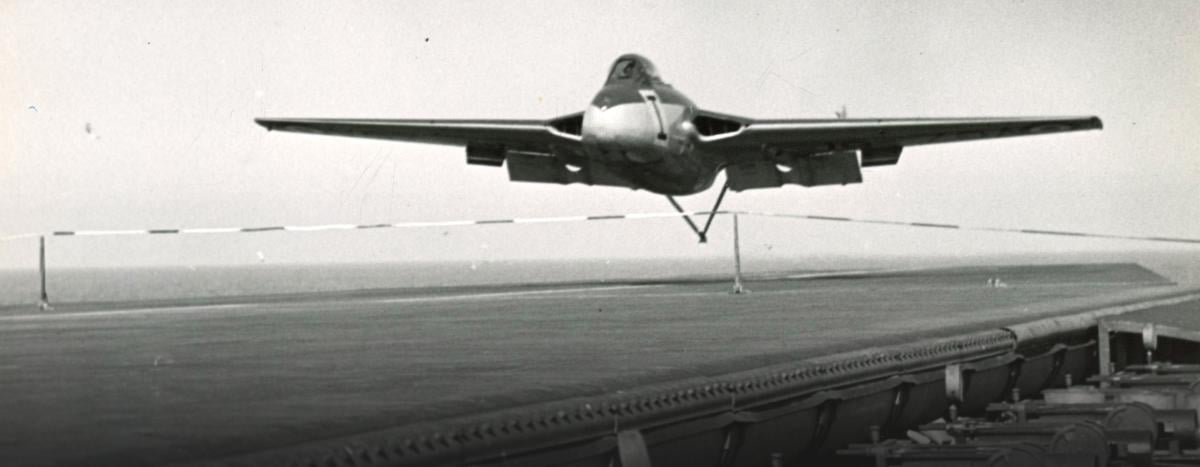

After that inauspicious first effort, several changes were made in the landing procedure, and, on 17 March 1948, Brown made a perfect flexible deck landing in a Sea Vampire with wheels retracted. More landings followed at Farnborough, and, on 3 November 1948, Brown landed on a flexible carpet installed on board the light aircraft carrier HMS Warrior.

The Warrior, recently returned from loan to the Canadian Navy, was provided with a flexible deck of a rubber-like material stretching 190 feet aft from her island structure. A single arresting wire was installed near the forward end of the false deck. A plane that caught the wire was pulled down onto the flexible carpet and slowed to a halt with a runout of only a few feet. A crane then lifted the aircraft onto a trolley; the trolley was winched forward for lowering to the hangar deck by elevator or to the catapult for launching.

The tests on the Warrior were conducted from November 1948 to May 1949. More than 200 landings, ashore and afloat, were made by Fleet Air Arm and Royal Air Force pilots, as well as a U.S. Navy test pilot, Lieutenant Commander (later Vice Admiral) Donald D. Engen.

There were no serious accidents. On occasion a plane would miss the single arresting wire, hit the carpet, and bounce into the air; the pilot then would simply fly around for another go. Evaluation of the tests indicated that the elimination of the undercarriage would represent a 4 to 5 percent saving in aircraft weight. This could lead to improved aircraft designs (e.g., thinner wings), with a saving of an additional 5 to 6 percent of gross weight. Translated into performance for carrier-type aircraft, that meant a 45-minute increase in endurance or a speed increase between 17 and 23 miles per hour.

The U.S. Navy in 1953 erected a 570- by 80-foot flexible deck at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland; again, a single arresting cable was provided. Two modified F9F-7 Cougar turbojet aircraft flew a total of 23 wheels-up landings onto the deck, piloted by a Grumman test pilot, a Marine Corps pilot, and a Navy pilot—Lieutenant John Moore. Those trials encountered numerous difficulties, and the concept again was abandoned.

One difficulty was that wheelless aircraft would require a flexible deck everywhere they went. They could not land at conventional airfields or come aboard carriers not provided with a flexible deck without causing major damage to the aircraft. The costs of rigging airfields ashore with flexible decks and developing a new generation of aircraft to take maximum advantage of the concept were not considered justified for the possible results gained.

Vice Admiral Engen, who had made seven landings in a Sea Vampire on the ashore rubber deck, later wrote:

Those tests were most interesting. I was not sure how practical the concept of building airplanes without landing gear would be. The ground-handling challenge would be enormous. . . . I made my report to the U.S. Navy without the ringing endorsement that I had given to the mirror [landing system], but still, new concepts have to be evaluated, and we had learned a great deal about that one. I had made seven wheels up landings—six of them intentionally.

Thus ended a most interesting—and totally unproductive—development in carrier aviation.

Sources:

VADM Donald Engen, USN (Ret.), Wings and Warriors: My Life as a Naval Aviator (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997).

CAPT Eric M. Brown, RN (Ret.), Wings on My Sleeve (London: Arthur Baker, 1961).

CDR John Moore, USN (Ret.), The Wrong Stuff: Flying on the Edge of Disaster (North Branch, MN: Specialty Press, 1997).