Stopping a ship has been problematic for centuries. The viscous medium of the sea provides little purchase for generating the friction needed to reduce a ship’s forward progress. The transition from sail to steam propulsion—and higher speeds—only made the problem more acute. Not long after steam became prevalent in the 1870s, the first patents for devices described as “ship brakes” were granted.

One of the earliest was prompted by the harrowing experience of the sister of Bostonian John McAdams on 11 June 1880. She was a passenger on the paddlewheel steamer Stonington, which collided amidships with the similar Narragansett in Long Island Sound off Saybrook, Connecticut. Although neither ship sank, 30 people were killed. As his sister described the event, McAdams conceived of an idea he said would “stop any vessel in from one to ten feet, no matter how fast” it was steaming. His notion was to anchor a pair of iron “shutters” or “fins” hinged on either side of the sternpost. When closed, the fins would lay flush with the hull, forward of the post. When required, crew in the pilothouse would release the fins, the water flow pulling them open to a 90-degree position, restrained by struts. He further added the safety of a “self-acting guard” attached to the bow, which when contacting a physical object would automatically release the fins, thus stopping the ship before the hull made contact.

In June 1882, after initial tests with a rowboat and a raft, McAdams tested his invention on a 37-foot “fast steam yacht.” With both fins deployed, the vessel stopped “instantly” from full speed. His invention was tested later that August, on the 50-ton sidewheel steamer City Point off Fort Winthrop in Boston Harbor. It was deemed “quite successful.”

“By actual measurement,” it was reported, the ship had not moved more than ten feet before the engineer had reversed her direction from her full speed of 12 miles per hour. They further tested the fins by having them fully deployed while attempting to steam ahead at full speed. “[T]he steamer refused to budge, and stuck like a rock in the water.”

McAdams and his invention disappeared from the press after these tests.

Mention of two other inventions can be found in very brief notices with no substantive information. The 11 August 1888 edition of the Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle of Portsmouth, England, had a four-sentence notice of a Royal Navy warship being fitted with “Pagan’s safety brake” for experiments. The other, from another English newspaper, The Leeds Mercury of 12 February 1892, noted under patents, “T. Halliwell, Castleford; the ‘Halliwell ship brake.’”

The effort at stopping a ship became more serious around the turn of the century. In 1898, Canadian court clerk Louis Joseph Lacoste began work on a device he called the “ship-brake.” The device was simple in concept. His idea was akin to McAdams’ but differed, in that his “doors” were mounted amidships and water “cushions” incorporated into the struts that restrained them perpendicular to the hull eased their opening. Lacoste also advocated using one door at a time to bring the ship about more quickly than with rudder only. When not needed, the doors were retracted by a strut-attached mechanism.

In 1901, Lacoste patented the brake and submitted his design to the British Admiralty and Canadian shipping firms, which all reacted favorably. In November 1902, the Lacoste Ship Brake was installed on the 103-foot-long, 250-ton Canadian government steamer Eureka and began testing. The first evaluation, made at half speed, resulted in a stop of less than 100 feet. With adjustments, Lacoste was able to get the ship stopped from full speed within 50 or 60 feet, and the ship could turn in her own length with one door deployed.

The Eureka was used for continued tests and demonstrations until June 1903, when she sank while being refueled. The brake played no part in the sinking—some ports had been left open, and the ship rapidly filled with water and went down. The Eureka was raised in July, and by mid-September, she again was running tests. In mid-May 1904, she collided with the Black Diamond Line steamer Bonavista, which was at anchor in Montreal Harbor. Unfortunately, the brake had been removed by this time, so it could not be tested in a real-world circumstance.

Lacoste continued to plead his case before shipping lines and builders, but apparently without much effect—until 1908. Early that year, a brief statement appeared that the Norwegian steamer Gwent was to be equipped with the brake, though there is no record this occurred. More significant was the 9 December announcement that “by direction” of President Theodore Roosevelt, the Navy Department was to give the Lacoste Ship Brake a trial. It would be installed on the USS Indiana (Battleship No. 1), then laid up in ordinary at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

Contemporary newspaper accounts noted: “Officers of the navy have very little regard for the brake” but must give it a trial “because of the political influence back of it.” The inventor had links to John A. Stewart, president of the New York State League of Republican Clubs, and Stewart had the ear of President Roosevelt.

Installation began in November 1909, and on 16 April 1910, the Indiana set sail for the tests off Lewes, Delaware. In the meantime, however, in March 1909, Richard F. Preusser, a locksmith in Washington, D.C., laid claim to the device’s invention. He claimed to have constructed a model of his idea in 1891 and demonstrated it to the Navy but was discouraged by their response. This claim quickly disappeared.

Of more significance was the actual inventor’s death on 13 April 1909. Lacoste had been overseeing the construction of one of his brakes at a Montreal shipyard when he contracted pneumonia and died a week later, at age 40. The Indiana began tests of his brake almost a year later.

Canadian reports of the four-day tests were effusive. Nevertheless, the U.S. Navy turned it down. The review board did not believe its advantages offset its disadvantages. Board members found the brake provided neither the promised short stopping distances nor the reduced turning radius, and its weight had to be offset by reduced coal or ammunition. Further, the board noted that without frequent use it would become clogged with marine growth.

In November 1910, a report hinted at the possibility of further tests, but this was laid to rest the following April when the Indiana was ordered to remove the brake. Discussion of the brake briefly resurfaced in April 1912, following the Titanic sinking, in some “what-if” articles.

In 1915, Navy Captain William S. Smith revived the Lacoste brake and conducted a series of tests at the Washington Navy Yard Experimental Model Basin. The test model took the lines of the St. Louis, a 536-foot, 17,230-ton steamer built in 1894. One of the conclusions was that the Indiana had been completely unsuitable as a test subject, because there was “not a straight line in any part of her hull” and the brake had to be molded to her form. Further, there was no accurate way of measuring power and speed.

Smith tested a total of 17 different size brakes and four forms of deployment at nine different speeds, ranging from 15 to 23 knots. Smith found that at 18 knots, the largest 12-foot by 14-foot brakes would slow the ship to 11.1 knots in 50 seconds and 4.7 knots in 200 seconds. While effective, these were not “stop on a dime” numbers.

Smith concluded that the simplest form of brake was the sole practical solution and that its use would be determined by finances. He designed such a brake for the Empress of Asia of the Canadian Pacific Steamships line; however, he later testified that the brake was never built.

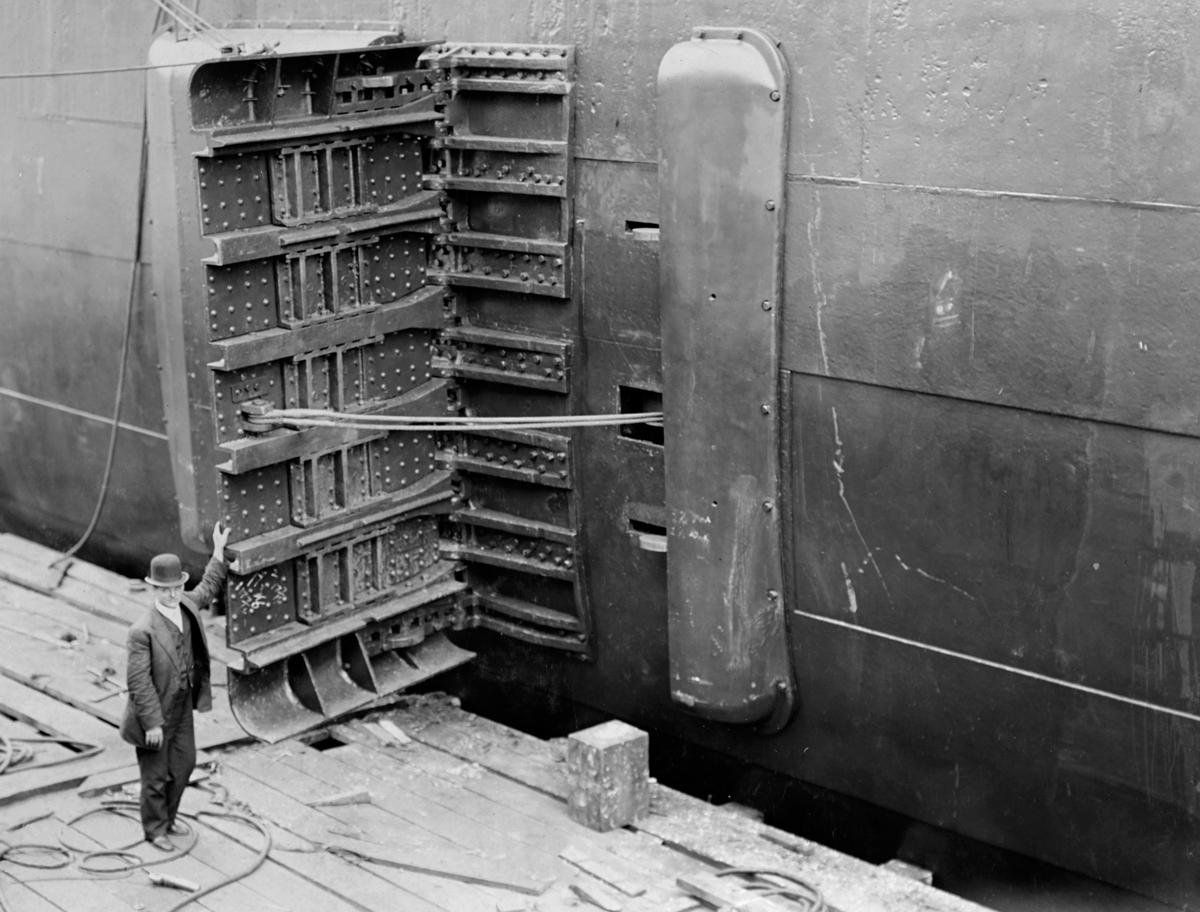

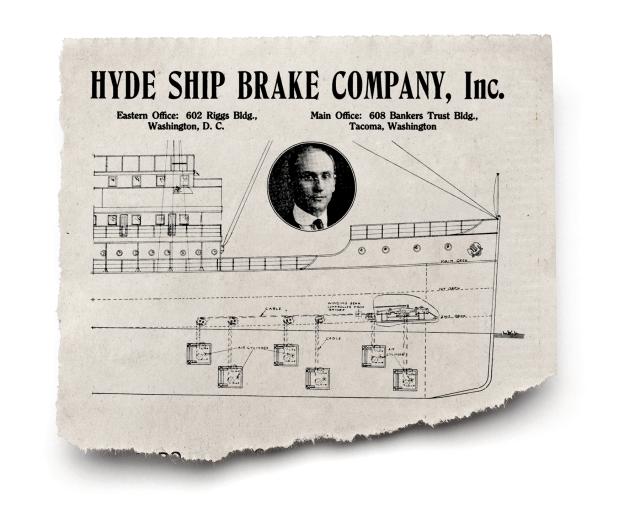

Almost simultaneous with Smith’s tests, in March 1915, lumber broker John H. Hyde of Tacoma, Washington, conducted similar tests. Hyde patented his design in February 1914 in response to the Titanic disaster. His device comprised a series of flaps along the bilges that would be opened to increase drag and slow the ship. Hyde frequently published large newspaper advertisements featuring the latest ship disaster news while seeking investors for $5 per share.

On 10 February 1916, Hyde demonstrated his invention with the tug Hesperus in Seattle Harbor, and then, over three days the following week, he conducted two demonstrations daily. The tug stopped in half its length from its maximum eight-knot speed. These appear to have been mere stunts to boost stock sales, which ran as high as $10 per share, than outright tests. By June, however, the ads had disappeared, with one final offering of 1,200 shares at $0.25 each.

One other similar approach was patented in 1918, but with that, drag-producing “barn door” solutions appear to have disappeared. Technological advances in ship propulsion and drive have resulted in less obtrusive and more integrated solutions, such as reversible-pitch propellers and thrust-vector pumpjets.