Mine warfare is often described as a cycle: A simple sea mine strikes an expensive warship, but no mine warfare forces are able to respond because mine warfare has been neglected; thereafter mine warfare receives some attention. After the conflict, however, mine warfare resumes its unsexy status—at least until the next mine strike.

During the Cold War, small European navies maintained NATO’s mine warfare readiness. This included both minelaying and mine countermeasures (MCM). However, after the demise of the Soviet Union, minelaying was quickly dismissed as the first benefit of the peace dividend, and the focus of mine warfare communities turned toward clearing the sea of war remnants. For other warfare communities, focus turned “out of area” altogether. As a result, NATO has lost its institutional mine warfare knowledge and, more broadly, coastal defense warfare knowledge, which is the type of warfare applicable to the Baltic Sea.

The character of mine warfare in the Baltic Sea has not changed but has been forgotten. Sea mines are still the central weapon, and mine warfare must be part of maritime and joint warfare.

New Setting

During the Cold War, Warsaw Pact war plans included a joint drive to the North Sea coast with some forces occupying strategic points along the Jutland peninsula near the entrances to the Baltic Sea. The Warsaw Pact’s combined Baltic Fleet’s task was to conduct amphibious landings in the Danish straits area, facilitate break out into the North Sea, link up with forces from the Soviet Northern Fleet, and conduct operations against the terminal parts of NATO’s transatlantic sea lines.1

NATO’s Baltic Sea power (i.e., the Royal Danish Navy and half of the Federal German Navy) was on the defensive and barely extended east of the islands of Bornholm, Denmark, or even Fehmarn, Germany. NATO’s sea-denial effort in the western Baltic was based on conventional submarines, anti-invasion minefields, small surface combatants, coastal artillery (later, missile batteries), and land-based maritime strike aircraft. This combined maritime defense of Danish, German, and surrounding waters was operationally directed by Commander, Naval Forces Baltic Approaches, subordinated to Commander, Baltic Approaches—a joint command responsible for defending allied sea and land areas from the Skagerrak Strait—which runs between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the south coast of Norway, and the west coast of Sweden—to Schleswig-Holstein, Germany’s northernmost state.2 Both were deactivated in 2002 after a post–Cold War restructuring.

The area of operations for mine warfare also was restricted to the western Baltic, where units were tasked to lay protective minefields and be ready to clear enemy mines from allied sea lines of communication.

Today, the front line has shifted east, and NATO has acquired three coastal “islands”: the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania; and new NATO members Sweden and Finland. It is a logistical reality that NATO needs freedom of navigation in the Baltic should it need to conduct any land fights in the Baltic states or Finland. The only land bridge between the Baltic states and Central Europe—the so-called Suwalki Gap between Lithuania and Poland—is too narrow to allow necessary logistical throughput. Finland depends entirely on maritime transportation.

Retired Danish Navy Rear Admiral Nils Wang wrote in 2018: “The difference between the Cold War and the current situation . . . [is] clear. The situation in the Baltic Sea [for NATO] thus turns into offensive the moment deterrence fails.”3 His statement is about to be acknowledged as NATO’s strategic approach: defense, and not just deterrence, followed by counterattack.

For mine warfare, the new geographic setting means that besides anti-invasion minefields, there is broader maneuver space available and more options for minelaying. NATO now has the geography to control maritime access to Kaliningrad, Russia, and to the Baltic Sea overall. On the other hand, the MCM task has become enormous—sea lines from the Strait of Kattegat (between Denmark and Sweden) to Riga, Latvia; Tallinn, Estonia; or Helsinki, Finland, are very long in terms of time for a mine-clearance operation.

New Plan

In planning for future battle in the Baltic Sea, one must note three aspects of mine warfare: physical factors, organic integration, and the joint character of the Baltic Sea.

Physical Factors

Writing about mine warfare during World War I, Sweden’s Commander Gunnar Möller concluded the Baltic Sea was ideal for mining because it has many narrows and choke points, is very shallow, allows minefields to be covered by fires from ashore, has no tide, and has long and dark nights.4 These physical factors have not changed, meaning sea mining is still the best strategic weapon in the Baltic Sea today and into the future, with more novel ways of “seabed warfare” emerging.

It is important to note that the object under the water—the mine—has the advantage over the countermeasure on or above the water. This is because seawater remains an opaque environment. Minelaying, therefore, is the stronger form of warfare compared with MCM. This theory continues to play out in the Black Sea: The minefields prevented a direct amphibious assault on Odessa, Ukraine, in 2022 and will cause trouble for years, if not decades, as was the case on the Baltic after both world wars.

Organic Integration

Mine warfare in the Baltic Sea must be an organic part of any maritime warfare and cannot be treated separately. The problem seems to be that in most nations, MCM has become an isolated branch. This is well illustrated by many naval exercises at sea during which the mine warfare portion is conducted somewhere “around the corner” and has little to do with the overall scenario.

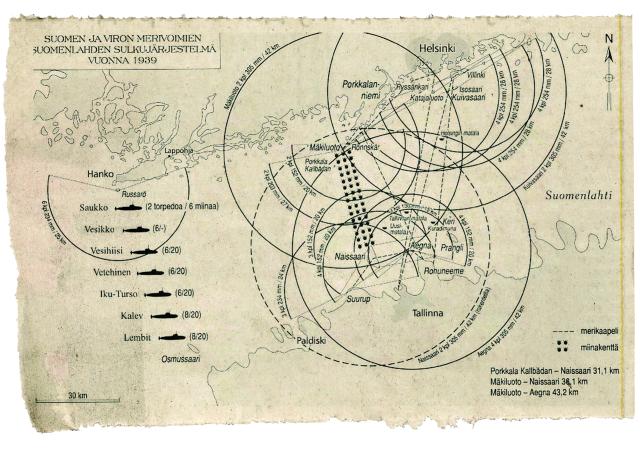

A simple maxim of army engineers is that obstacles must be covered by observation and fires to be effective and last longer. The prime example is Russia’s invention of the so-called mine-artillery position. It was first used during the 1853–56 Crimean War and further developed prior to World War I for use at Peter the Great’s maritime fortress in the Gulf of Finland to defend against a possible German direct assault on St. Petersburg. During the 1930s, Estonia and Finland used observation and fires in combination with minefields to bottle up the Soviets in the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland, and Finland and Germany did the same against Soviet Union in 1941–43.5

In 1939, the so-called Gulf of Finland lock consisted of minefields, covered by large-caliber coastal guns that were centrally directed using the direct underwater phone cables across the gulf. Both shores were covered by visual observation posts already in use during peacetime, and contact data was exchanged by the same cable network. In addition, coastal submarines were used for minelaying and surface attack as part of this bilateral defense system.6

Antiacess/area-denial is nothing more than coastal defense through joint and technological prisms.7

Joint Character

Mine warfare has a joint character in the Baltic Sea. One attribute of sea mines is that they can change the geography. Because of this, minefields were laid in relation to front lines ashore during both world wars.

World War I naval fighting in the Baltic was almost entirely mine warfare, with very few surface actions and only one major amphibious landing. Russian offensive mining in 1914 in the waters north of Pomerania (currently northern Poland) took place behind the front line ashore with the aim of harassing German supply lines. By 1915, the front line had moved well into Latvia (River Daugava) and extended into neutral Swedish waters near Gotland by a barrier line that included minefields and minefield guard ships.

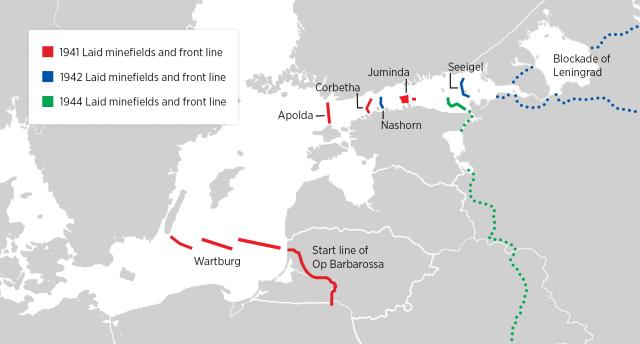

The Germans perfected strategic minelaying as part of joint campaigning during World War II. A few nights before Operation Barbarossa began on 22 July 1941, minefields Wartburg, Apolda, and Corbetha were laid in the Baltic. The Wartburg minefields between Klaipeda in Lithuania and the Swedish island of Öland illustrate the risk to the minelayer itself. These minefields turned into a problem for Germans themselves rather than the Russians, illustrating that the decision to lay mines will affect everyone in the Baltic Sea—directly or indirectly.8

Minelaying continued in the Gulf of Finland after the outbreak of hostilities in cooperation with Finland, which had sided with Germany. This combined minelaying ended with the so-called Juminda mine battle, during which retreating Soviet forces and deported civilians suffered heavy losses in late August 1941. In 1942, the blockade of Leningrad was completed by the Seeigel minefields in the eastern Gulf of Finland, and the Gulf of Finland lock (minefield Nashorn) also was completed and became active. In 1944, when the front line started to move west and stopped for a while on the Narva River (now the eastern border of Estonia), flanking minefields were laid to avoid Soviet amphibious envelopment.

Historical minefields in the Baltic Sea were all tied to suitable areas for mining and/or ports and choke points, which have not changed, and/or land borders, which have. Therefore, these historical minefields also inform the future—they are where the future mine battles most likely will be fought.

Mine Countermeasures

Because mine warfare must be an organic part of maritime and joint warfare in the Baltic Sea also holds true for MCM. The MCM priority should be to prevent enemy mines from being laid using strategic bombing (or strike warfare) and antisurface action to destroy enemy mine depots and minelayers. If hostile mines are laid in allied waters, the priority falls to avoiding them by guiding shipping around the threat areas. If that is not possible, specialist MCM forces, such as Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group 1, will come into play; however, this is the worst-case scenario, because clearing mines will take a long time.

The Future of Mine Warfare

Since the Cold War, NATO’s operational geography has enlarged, offering more options for minelaying but also a bigger MCM challenge.

The challenge for NATO, however, is organizational, as the Baltic Sea east of Bornholm, Denmark, is a new theater of operations, and the institutional knowledge of sea mines has atrophied. The alliance must acknowledge naval mines as the central maritime weapon in the Baltic Sea. In addition, as a specific maritime theater, the Baltic Sea requires a separate and expert maritime command-and-control element within the framework of approved regional plans focused on coastal defense warfare, including mine warfare. Commander, Naval Forces Baltic Approaches, filled this role in the western Baltic during the late Cold War era. In 2024, German Maritime Forces Headquarters is about to take the lead on maritime warfare in the Baltic Sea—and hopefully return mine warfare expertise to NATO’s command structure.

1. Vojtech Mastny, Sven Holtsmark, Andreas Wenger, eds., War Plans and Alliances in the Cold War (London and New York: Routledge, 2006).

2. Philip A. Petersen, The Northwestern TVD in Soviet Operational-Strategic Planning (Vienna, VA: The Potomac Foundation, 2014), 66–92.

3. N. Wang, “Danmarks Strategiske Udfordringer i Østersøen—et Sømilitært Perspektiv,” Krigsvidenskab.dk (January 2018).

4. Gunnar Möller, The Mine War in the Baltic Sea 1914–1915 [English translation] (Columbus Förlag, 2016), 94–95.

5. LCDR Jason D. Menarchik, USN, “North Korean Protective Mine Warfare: An Analysis of the Naval Minefields at Wonsan, Chinnampo and Hungnam during the Korean War” (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air Command And Staff College, 2010).

6. Jari Leskinen, State Secrets of the Brothers: Finland and Estonia’s Secret Military Cooperation in Case of an Attack by the Soviet Union 1918–1940 [English translation] (Finland, Helsinki: WSOY, 1999).

7. CDR BJ Armstrong, USN, “The Shadow of Air-Sea Battle and the Sinking of A2AD,” War on the Rocks, 5 October 2016.

8. P. O. Ekman, “Minor för Barbarossa,” Tidskrift för Sjöväsendet no. 4. (1976): 196–216.