In 2016, ocean drones captured international attention when a Chinese warship in the South China Sea seized an oceanographic glider that was in the process of being retrieved by the U.S. Navy survey ship USNS Bowditch (T-AGS-62). At the time, I had administrative control of that uncrewed underwater vehicle (UUV), and I was not only pleased that the Chinese returned the vehicle, but also happy to help the Navy’s Chief of Information use the incident to cast an embarrassing worldwide spotlight on China’s latest violation of international law.

Although ocean drones appeared novel to the public back then, various types of surface and underwater robots have been conducting both research and military missions for decades. The first uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) were used in the 1920s as remote-controlled target craft, while the first autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) was created in 1957 to perform research in the Arctic for the University of Washington.

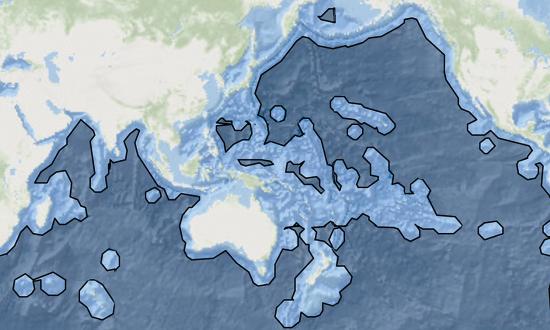

Since then, the ocean science community—often in partnership with government agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Office of Naval Research (ONR)—has been at the leading edge of developments in ocean drones. Applications have included physical, biological, chemical, and geological oceanography, underwater acoustics, and marine meteorology, while the technology trends have progressed from purpose-built single-mission vehicles, to multipurpose platforms with modular payloads, to integrated groups of USVs and UUVs/AUVs. Further, NOAA has designed its next oceanographic ship class from the keel up as ocean drone motherships—the first federally funded vessel class of its kind in the United States.

Others have been eager adopters of marine robotics, including the offshore energy industry, NATO, and the U.S. Navy. For more than 20 years, the Navy has operated AUVs and UUVs for oceanographic, mine warfare, antisubmarine warfare, and Naval Special Warfare missions. In 2004, I was on board the Bowditch in the East China Sea during the first deployment of a glider UUV from a Navy oceanographic ship. Now, the Navy has a few hundred vehicles in several size classes ranging from sailor-portable to school bus sized.

USVs have been a more recent development for the Navy, with initial efforts using small-boat-sized platforms focused on mine countermeasures. In recent years, the Navy has experimented with two classes of drone ships. The smaller variant is the length of a patrol craft and intended for intelligence collection and electronic warfare, while the larger USV is akin to a small frigate and designed to carry antiship and land-attack payloads. All USVs are managed under formal acquisition programs, and four of the larger two types of ships recently completed a deployment to the western Pacific.

Other ocean drone developments have occurred overseas. The Navy’s Fifth Fleet established Task Force 59 in 2021 to experiment with contractor-owned, contractor-operated USVs for maritime domain awareness. Capturing even greater attention are the multiple successful USV strikes by Ukraine on Russian ships in the Black Sea since 2022.

With all this ocean drone activity, it is no surprise China has rapidly developed and deployed capabilities comparable to or exceeding those of the United States. As one example, China’s Haidou-1 AUV set the world depth-diving record for an uncrewed submersible, reaching 10,908 meters in 2021. This in part is the reason for the Defense Department’s new Replicator initiative, which intends to deliver thousands of attritable, all-domain, autonomous systems to counter the rapid growth of China’s armed forces. Kinetic interceptors will be included through the production-ready, inexpensive, maritime expeditionary small USV solicitation by the Defense Innovation University.

Just how this marine robot revolution unfolds is anyone’s guess, but one thing is certain: If China gets back in the business of stealing U.S. ocean drones, there will be no small number from which to choose.