A Chinese invasion of Taiwan would prompt a major crisis between China and the United States, with significant repercussions for the Indo-Pacific region and the rest of the world. Such a crisis almost certainly would include implicit or explicit Chinese nuclear threats, despite Beijing’s longstanding no-first-use (NFU) policy. The United States can diminish the potential for China to leverage nuclear threats during a Taiwan crisis, but only if it moves with alacrity to strengthen conventional and nuclear deterrence. The Navy has a key role to play in achieving this goal.

Renewed interest in China’s nuclear program spiked after the 2021 discovery of three new missile fields in north central China. In January 2023, U.S. Strategic Command officially notified Congress that China has more intercontinental ballistic missile launchers than the United States.1 Yet, when it comes to assessing specific Taiwan invasion scenarios, Western analysts often downplay the nuclear dimension. In January 2023, for example, a major Center for Strategic and International Studies Taiwan wargame focused exclusively on conventional warfare, altogether sidestepping the potential for nuclear escalation.2 The Pentagon’s 2023 annual assessment of China’s military power makes a passing reference to the possibility of “nuclear activities” in a Taiwan scenario, but only in the context of a “protracted conflict.”3

NFU Policy

China’s NFU policy is one reason nuclear threats in Taiwan invasion scenarios have not received adequate scrutiny. For decades, China has declared it will never be the first to use nuclear weapons under any circumstances. It would be a mistake, however, to take China’s NFU policy at face value. For starters, predicting China’s behavior in crisis situations is far from an exact science. As Center for a New American Security analyst Jacob Stokes argues, “Decisions with such grand strategic importance are likely to be informed by the worldview of China’s leadership—especially Xi [Jinping] himself for the foreseeable future—in ways that supersede official doctrine or other strategic analysis written by military bureaucracies or analysts.”4

At the very least, a Chinese invasion of Taiwan would provide a major stress test of its NFU policy if the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) struggled to subdue the island with conventional force. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders might even consider failure an existential threat. As defense analyst Mike Sweeney at Defense Priorities put it:

Any battle over Taiwan will not just be a question of territorial aggression but a fight over the core conception of modern China’s soul. And for the leaders who launch such an endeavor, their political futures will hinge on the outcome, as will, possibly, their physical safety and that of their families in the event of failure. Under such circumstances, nuclear use might not be palatable, but it could seem far more plausible if military defeat were to equate to loss of domestic power and possible death anyway.5

It has become conventional wisdom among China watchers that if China’s leaders decide to invade Taiwan, there is nothing anyone can do to change their minds. If true, this provides another reason to consider potential Chinese nuclear threats, since the “stop at nothing” narrative logically entails escalation if conventional means fail to achieve success.

These considerations raise the question of how China might use nuclear threats in a Taiwan invasion. Notably, there is evidence that not all Chinese military theorists believe using nuclear weapons on their own soil (which they consider Taiwan to be) would constitute a violation of the NFU policy.6 That said, it is difficult to imagine circumstances in which China might be tempted to use nuclear weapons on the island itself. It is more plausible to imagine Beijing launching an electromagnetic pulse attack over Taiwan.7 In theory, such a weapon could paralyze the island’s communication networks. Inflicting such a sudden and massive psychological blow might, in turn, shock Taipei’s political leaders into capitulation.

China also could use nuclear threats to dissuade the United States from rendering military assistance to Taiwan during a crisis. Here, it is worth recalling that senior Chinese officials have already issued such threats against the United States, as happened during the Taiwan crisis in 1996 and again in 2005.8 What is more, Chinese military publications and journals have mentioned—on multiple occasions—the potential for nuclear first strikes against the United States as part of various Taiwan invasion scenarios.9

China might seek to leverage its nuclear weapons in a future Taiwan crisis without resorting to explicit nuclear threats. Since a good portion of the PLA’s nuclear forces are based on mobile platforms, it could disperse them during a crisis to assume a more threatening posture.10 It also could adjust nuclear alert levels to signal intent. If these measures did not deter third-party intervention, China could resort to more dramatic action, such as firing a nuclear demonstration shot near Taiwan, Okinawa, Guam, or even Hawaii during an invasion crisis.

One might counter that China is unlikely to cross the nuclear threshold in a Taiwan conflict for fear of international condemnation. This may well be the case, at least initially. But China could reconsider its position, especially if third-party intervention threatened to derail its invasion plans. It is worth remembering that China did not intend to issue nuclear threats when it instigated its 1969 border war with the Soviet Union. But eventually Beijing did exactly that after it feared the Soviets might escalate the conflict.11

China’s Growing Nuclear Arsenal

The growth of China’s nuclear arsenal may increase its willingness to issue nuclear threats in the future. To understand why, it is important to recall China’s nuclear history. At the dawn of the Nuclear Age, China sought to diminish the importance of nuclear weapons. In 1946, CCP Chairman Mao Zedong famously denigrated the bomb as nothing more than a “paper tiger.” Mao made a virtue of necessity because China did not have the technological means to develop nuclear weapons until 1964. For decades afterward, China appeared content with a small nuclear arsenal, confident it could deter the United States—and later the Soviet Union—with an assured second-strike capability. But the discovery of China’s new missile fields in 2021 suggests Beijing’s nuclear doctrine is changing.

China’s decision to dramatically expand its nuclear capabilities is the most consequential development in the PLA’s ongoing modernization efforts. As the Pentagon’s 2023 annual report put it, “Over the next decade, the PRC will continue to rapidly modernize, diversify, and expand its nuclear forces. Compared to the PLA’s nuclear modernization efforts a decade ago, current efforts dwarf previous attempts in both scale and complexity [emphasis added].”12

Over time, China’s nuclear arsenal expansion may embolden its behavior—including the propensity to issue nuclear threats.13 As the 2021 U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission report asserts, “It could also be intended to support a new strategy of limited nuclear first use. Such a strategy would enable Chinese leaders to leverage their nuclear forces to accomplish Chinese political objectives beyond survival, such as coercing another state or deterring U.S. intervention in a war over Taiwan.”14

The United States still maintains an advantage in terms of strategic warheads, but the PLA is closing the gap. In its 2023 report on Chinese military power, the Pentagon estimates China “will probably have over 1,000 operational nuclear warheads by 2030.”15 The fact that the U.S. nuclear arsenal will remain larger than China’s for at least the next few years provides no guarantee that Beijing will refrain from nuclear threats in the near term. Historically, China has demonstrated a willingness to instigate crises, even against stronger military powers, to achieve political aims.16 Moreover, Chinese writings have long focused on the political nature of nuclear weapons, especially their potential to inflict psychological shock. All this should be front of mind when considering the potential for China to resort to nuclear threats during a Taiwan invasion, whether in the near or distant future.

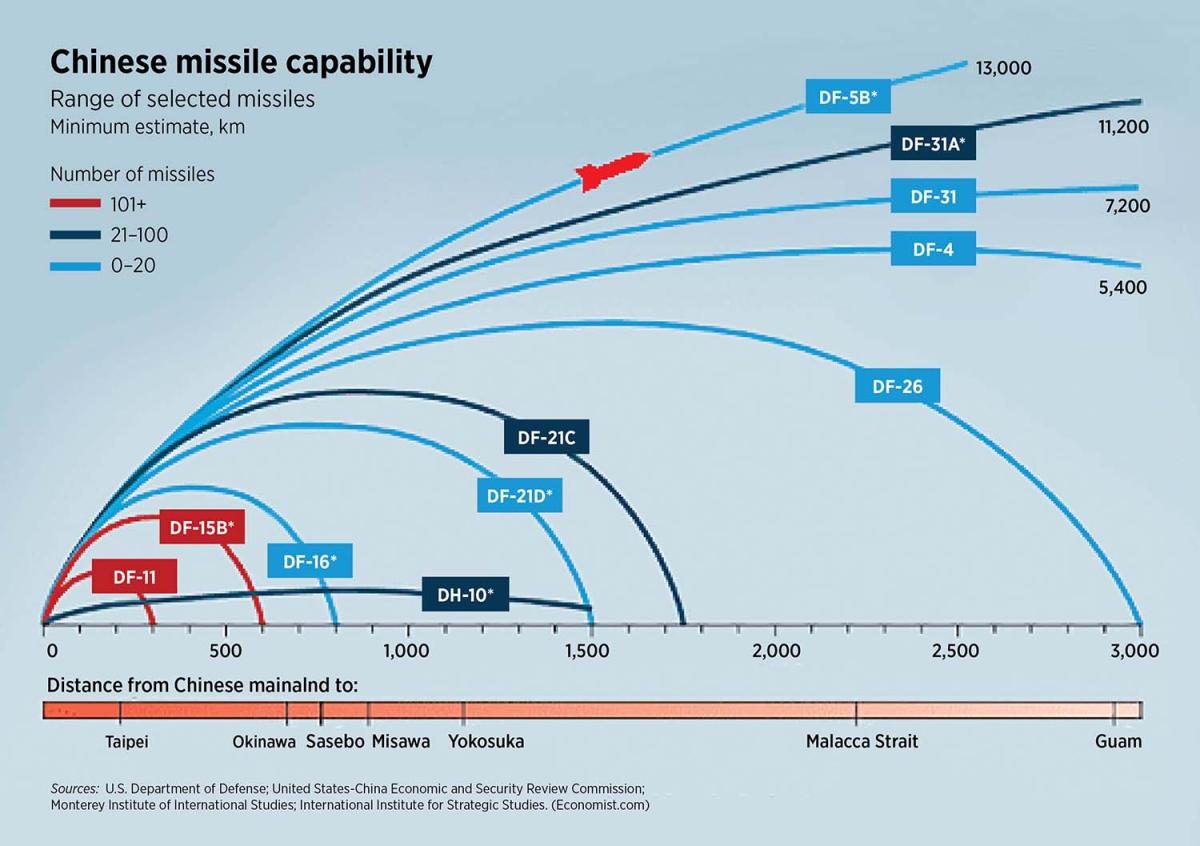

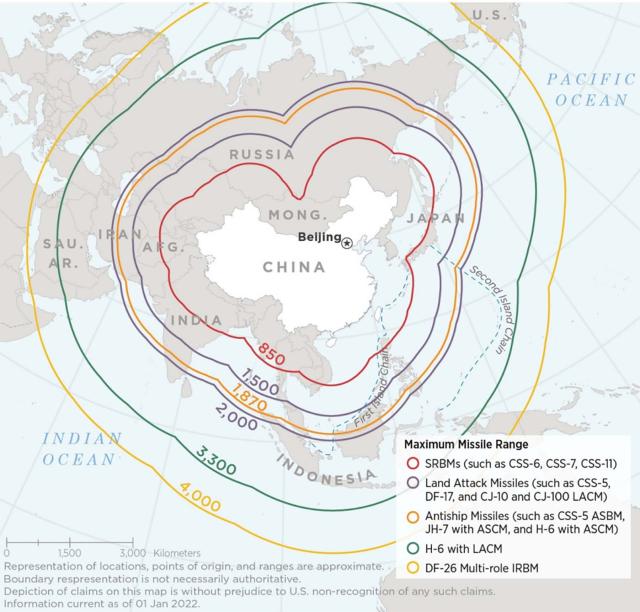

The nature of the PLA’s force structure also increases the odds that the next major crisis over Taiwan will include a nuclear dimension. The dual-use capability of selected Chinese missiles, such as the DF-26 “carrier killer,” means the PLA can exchange conventional warheads for nuclear ones in short order. This would present special intelligence and operational challenges for the U.S. Navy during a conflict over Taiwan. In addition, the PLA’s commingling of conventional and nuclear weapons raises the risk of inadvertent nuclear escalation since the Pentagon’s playbook normally involves precision strikes deep into enemy territory.17

Nuclear Threats Extend to U.S. Allies

The United States also must consider the possibility that China may issue nuclear threats against one (or more) U.S. allies in a Taiwan scenario. Washington’s greatest strength in the Indo-Pacific theater is its extensive web of allies and partners. China understands this full well, which explains its relentless efforts to sow discord among them. In the event of a Taiwan crisis, China will intensify these efforts.

China knows that Japan is the most important U.S. ally when it comes to Taiwan, because Washington depends on Japan for military basing and diplomatic support. It should come as no surprise that Chinese officials already have sanctioned a crude nuclear threat against Tokyo. In July 2021, a video surfaced on a CCP-approved channel linked to the PLA that declared, “We are warning Japan and informing the world that if Japan interferes militarily in our domestic affairs—including the unification of Taiwan with the mainland—nuclear weapons will surely be used against them.”18

Japan is not the only U.S. ally that China has threatened with nuclear weapons. China also has threatened Australia over its participation in a nuclear submarine deal with the United States and the United Kingdom. In 2021, an article in the CCP mouthpiece Global Times asserted that such developments “will potentially make Australia a target of a nuclear strike.”19 These examples highlight the need for Washington to coordinate with key allies to neuter the potential impact of Chinese nuclear saber rattling.

Washington’s interest in counterproliferation is another reason to take the growth of China’s nuclear arsenal seriously. In this vein, recall that Taiwan pursued a nuclear weapons program for decades before relinquishing its nuclear ambitions in the 1980s. Taipei’s leaders may be tempted to restart the island’s long-defunct nuclear program if they conclude no other course of action can deter a Chinese invasion. Then-President Lee Teng-hui declared Taiwan was reconsidering its nuclear option during the July 1995 crisis with China, though he walked back his statement a few days later. Taiwan has given no indication it is presently reconsidering its nonnuclear status, but its calculus could change over time.20

What is to be Done?

Clearly, the safest way to deal with a potential nuclear crisis is to prevent it from arising in the first place. For this reason, the United States must redouble its efforts to make Taiwan an indigestible porcupine from China’s perspective. This means ensuring Taiwan’s defensive quills are long, sharp, and numerous.

Beyond strengthening Taiwan’s defenses, the United States should take additional measures to bolster deterrence, most of which could be implemented quickly and at low cost.

• Senior U.S. civilian leaders need to participate more often in wargames focused on Taiwan invasion scenarios. More precisely, they need to think through the dynamics of Chinese nuclear threats and how best to respond to them during a crisis, regardless of how uncomfortable these scenarios make them. A sustained and focused effort along these lines would help raise the “nuclear IQ” among decision-makers and staff members who advise them.

The White House should require participation from senior officials at the Departments of Defense, State, and Homeland Security and the intelligence community and other relevant agencies. Moreover, the White House also should invite senior leaders from key allied countries in the Indo-Pacific theater to participate. There is no excuse for senior civilian leaders not to have thought through the potential nuclear dynamics of a Taiwan invasion.

• The United States must keep its strategic nuclear modernization efforts on track. It is vital to sustain the bipartisan consensus for replacing the aging land-, air-, and sea-based legs of the nuclear triad. Washington will be less likely to achieve its political-military goals in the Indo-Pacific region—or anywhere else—if its strategic deterrence credibility erodes. Maintaining a strong strategic deterrent is more important than ever given the growing sophistication of both Chinese and Russian strategic capabilities, as well as the possibility of military collaboration between them during a crisis.

• Congress should continue to fund the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) for U.S. attack submarines. The Navy used to have nuclear-armed Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles (TLAM-N), but President George H. W. Bush ordered them removed from surface ships and submarines in 1991. While this decision made sense in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, it no longer does today. As former defense officials Robert Soofer and Walter Slocombe have argued:

Fielding SLCM-Ns would demonstrate that the United States has optimal capabilities to respond to small-scale nuclear use by an adversary. The current relative lack of flexible options for a nuclear response may leave adversaries with the mistaken notion that they could “get away with” small-scale nuclear use without facing unacceptable consequences.21

In other words, equipping the Navy with this capability would add an important rung to the escalation ladder, providing U.S. leaders with more options in a crisis. Equally important, it would complicate PLA war planning and, thereby, strengthen nuclear deterrence.

• To further defang the potential coercive power of Chinese nuclear threats, the Navy must strengthen its capacity to hold PLA nuclear assets at risk in the Indo-Pacific theater. The Navy has a key role to play in tracking the PLAN’s submarines—a challenge that has become more difficult with increasingly long-range PLAN deployments in the South China Sea and elsewhere.22

• The Navy should strengthen its Aegis ballistic-missile defense system by increasing the number of SM-3 interceptors it can deploy. The Navy also should practice surging its missile-defense capabilities in the event of a crisis. This should include increasing the size, scope, and duration of missile-defense exercises, preferably in concert with the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, which also has Aegis missile-defense destroyers.

• The Navy–Marine Corps team must strengthen its capabilities to fight in—and through—nuclear contaminated environments. Such efforts could help dissuade Chinese decision-makers from concluding they could easily intimidate U.S. forces stationed in, or surged to, the Indo-Pacific region with nuclear threats.

Deterring a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is no easy undertaking. Strategists and military planners must lean into hard problems, not away from them. No single measure outlined above is likely to change China’s decision-making about whether to invade Taiwan or pursue its subjugation by other means. But if the United States implements these measures with a sense of urgency, it will help enhance deterrence.

In October 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis took Kennedy administration officials by surprise. Today’s leaders have no excuse for getting caught flat-footed. The broad contours of a Taiwan invasion crisis are already visible on the horizon—and they will almost certainly include nuclear storm clouds. The time to prepare is now.

1. Greg Hadley, “China Now Has More ICBM Launchers than the U.S.,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, 7 February 2023.

2. The CSIS wargame simulated military command authorities but “no political and nuclear decision-making.” Mark Cancian et al., The First Battle of the Next War (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic Security and International Studies, January 2023).

3. U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, annual report to Congress (October 2023), 140.

4. Jacob Stokes, Atomic Straits: How China’s Nuclear Buildup Shapes Security Dynamics with Taiwan and the United States (Washington, DC: Center for New American Security, February 2023), 9.

5. Mike Sweeney, “Why a Taiwan Conflict Could Go Nuclear,” Defense Priorities, 4 March 2021.

6. Kenneth W. Allen, “China’s Perspective on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons and Arms Control,” in Jeffrey Larsen and Kurt Klingenberger, eds., Controlling Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons (U.S. Air Force Academy, CO: USAF Institute for National Security Studies, 2001), 162.

7. Peter Pry, China: EMP Threat, EMP Task Force on National and Homeland Security, 10 June 2020.

8. Barton Gellman, “U.S. and China Nearly Came to Blows in ’96,” The Washington Post, 21 June 1998; and Joseph Kahn, “Chinese General Threatens Use of A-Bombs If U.S. Intrudes,” The New York Times, 15 July 2005.

9. Mark Schneider, The Nuclear Doctrine and Forces of the People’s Republic of China (Fairfax, VA: National Institute of Public Policy, November 2007), 7–8.

10. “China’s Nuclear Forces: Moving Beyond a Minimal Deterrent,” report to Congress by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (November 2021), 350, 357.

11. Caitlin Talmadge, “The U.S.-China Nuclear Relationship: Growing Escalation Risks and Implications for the Future,” testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on China’s Nuclear Forces, 7 June 2021, 8, 9.

12. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments, viii.

13. Michael Tkacik, “Will China Embrace Nuclear Brinkmanship as It Reaches Nuclear Parity?” The Diplomat, 5 August 2023.

14. “China’s Nuclear Forces,” 340.

15. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments, VIII.

16. Mark Burles and Abram N. Shusky, Patterns in China’s Use of Force: Evidence from History and Doctrinal Writings (Arlington, VA: RAND Corporation, 2000).

17. Caitlin Talmadge, “Beijing’s Nuclear Option: Why a U.S.-Chinese War Could Spiral Out of Control,” Foreign Affairs 97, no. 6 (November/December 2018).

18. See Jamie Seidel, “China Threatens to Nuke Japan If Country Intervenes in Taiwan Conflict,” news.com.au, 19 July 2021.

19. Yang Sheng, “Nuke Sub Deal Could Make Australia ‘Potential Nuclear War Target,” Global Times, 16 September 2021; see also Ben Graham, “‘Brainless’ Australia a Target for ‘Nuclear War,’ Warns Top China Expert,” news.com.au, 21 September 2021.

20. See Alex Littlefield and Adam Lowther, “Would a Nuclear-Armed Taiwan Deter China?” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 24 December 2020; and Kyle Mizokami, “China’s Greatest Nightmare: Taiwan Armed with Nuclear Weapons,” The National Interest, 12 September 2019.

21. Robert Soofer and Walter B. Slocombe, “Congress Should Fund the Nuclear Sea-Launched Cruise Missile,” Atlantic Council, 3 August 2023.

22. Gabriel Honrada, “China Intensifies Nuclear Strike Threat in South China Sea,” Asian Times, 5 April 2023.