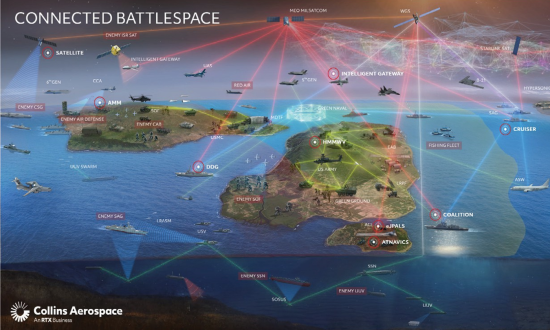

While the Department of Defense has funded many programs, concepts, and systems designed to enhance and coordinate effects across all services and domains, much of the connective tissue and critical requirements remain absent or overlooked. Command and control (C2) that enables integrated mission planning, communication standards, battlespace management, and tactical contracts will be critical for future success.

The overarching Department of Defense strategy to adapt to joint all-domain operations (JADO) is Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), which is designed to empower joint force commanders with the capabilities needed to command the force across all warfighting domains and throughout the electromagnetic spectrum.1 Among the five distinct lines of effort, which are mostly technical, only line of effort 2 (Human Enterprise) addresses the need to develop updated policies, doctrine, and tactics, techniques, and procedures.2

A quick survey of changes throughout the joint force reveals a Navy not moving at the necessary pace the Human Enterprise line of effort requires. The Army has created entirely new commands, including the multidomain task forces—theater-level maneuver elements that synchronize long-range precision fires and effects across domains.3 Likewise, the Marine Corps’ force redesign includes the Marine littoral regiments, new warfighting concepts, and a comprehensive training redesign intended to enable JADO.4 The Air Force has advanced new concepts for JADO, including agile combat employment, and has invested in programmatically elevating joint expertise into force-wide training.5 The Navy has not been idle, with the creation of entities such as the maritime intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance weapons and tactics instructors (MISR WTIs) and Task Force 76/3, which blends Navy and Marine Corps C2. However, the priority has been technical solutions that leave the human and organizational element unaddressed.6

To analyze where the gaps exist in C2 across JADO, it is best to begin from the terminal area and work backward. One tenet of JADC2 is centralized command, distributed control, and decentralized execution. This model can serve as a framework for understanding where the Human Enterprise has not kept pace with the technical developments and aspirations of a true joint all-domain C2 capability.

Decentralized Execution

Training the force to think and speak joint and multidomain is hard, and connecting tactical resources is harder. Failure during a joint or multidomain strike often results from some combination of timing, tempo, and the inability to coordinate and communicate in real time. Warships, bombers, and littoral batteries need to be able to speak to each other. No matter the planning, every mission has a “far side of the moon” moment when the controlling headquarters loses communication and situational awareness. These are the moments when the ability of the participants in a joint multidomain strike to communicate, coordinate, and flex in real time will be the difference between success and catastrophe. As Captain Wayne Hughes Jr. notes in Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, “Planning and execution are related, but they are not one in the same . . . one does not plan during execution; one executes a plan that incorporates tactical variations and permits alteration in execution.”7

This observation underpins a reality being ignored in favor of achieving either decentralized all-domain execution or centralized joint task force (JTF)–directed execution. Success of any plan, but especially a mission designed to mass joint fires, still relies on tactical control in execution. It is essential for joint forces to coordinate, adapt, and overcome challenges together at the tactical edge. This happens organically in a single-service environment. Across domains and services, it must be cultivated, enabled, and trained to.

Getting a B-1 bomber to integrate with a guided-missile destroyer is difficult—and certainly not automatic. The relationships between the Air Force and ground forces, on the other hand, have been diligently cultivated since the introduction of the AirLand Battle concept in 1982.8 Manifestations of 40 years of joint air-land integration exist in doctrine, systems, and C2. One of the best examples is the joint terminal attack controller (JTAC), certified to link tactical forces on the battlefield to air power.9 JTACs prove that trained specialists are necessary to bridge the gap between a section of strike fighters and a dismounted platoon. Maritime-focused JADO at the tactical level will require something similar. While aircraft across the services can achieve a high level of interoperability with the joint force via maritime air controllers, the same cannot be said for ships or ground forces without an intermediary.

A potential solution could be to create a similar cadre of specialists trained to integrate and direct fires and effects from all domains. A maritime terminal attack controller (MTAC) could be the missing link for Navy JADO. More than a traditional operations specialist air controller or a tactical air control squadron, an MTAC should be trained in the fundamentals of close-air support, joint capabilities, targeting, and maritime fires and be able to communicate with and control aircraft, warships, and littoral fires as well as request nonkinetic effects. With access to data, line-of-sight and satellite voice communications, and IP-based communications, MTACs on ships, in aircraft, or on shore could be the specialized synchronizers necessary to facilitate dynamic naval warfare in a joint environment.

When coexisting with MISR WTIs, this team would have a potent ability to perceive the environment and act accordingly. Ultimately, decentralizing execution requires more than just MTACs. Heightened joint force awareness and integration developed through continued exercising, a cadre of specialized experts, and common joint standards set the conditions for success at the forward edge.

Distributed Control

If failure at the tactical level of JADO results in breakdowns and uneven execution, poorly distributed C2 is mostly to blame. The planning, concept of operations, synchronization of fires, and many joint theater enabling functions (e.g., multiservice communication plans, datalink requirements, and coordinated intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting) reside at this layer of C2. These are the centers, cells, and C2 nodes that practice operational art to plan, prepare, synchronize, and sustain combat operations. As B. A. Friedman describes in On Operations: Operational Art and Military Disciplines, this is when “the disciplines required to place military forces in advantageous position to employ tactics to achieve strategic effect” come together.10

To begin a review of Navy distributed control capability, it is best to start with what the Navy currently intends to use at this level—the numbered fleets and their maritime operations centers. As Joint Publication 3-32: Command and Control of Joint Maritime Operations states, “The U.S. Navy’s traditional and doctrinal warfighting configuration is the fleet, commanded by a numbered fleet commander.”11 The Navy Staff Officer’s Guide also notes that “in a high-end maritime fight against a peer adversary, the fleet is the Navy’s basic maneuver element.”12 This description of the Navy’s intended C2 design and understanding of high-end maritime conflict is reflected in current doctrine and practice. That said, it is not clear if a numbered fleet commander and his or her maritime operations center should be the optimum maneuver element or a distributed control node for JADO—or whether either is even possible in the case of embarked fleet staffs. Real constraints in staffing, processes, doctrine, and capabilities currently diminish the ability of the numbered fleets to plan, prepare, or C2 such operations. In practice, and likely as a result of the culture of mission command, fleet MOCs have a tendency to demand situational awareness from their subordinates in greater measure than they provide it via orders, plans, and control.

The Joint Staff best-practices focus paper, “JTF C2 and Organization,” quotes an unnamed senior officer as saying, “At the end of the day, a Higher HQ must provide value added to its subordinates in things like intelligence analysis, ISR, fires, key leader engagement, and synchronization.”13 For JADO, C2 nodes need to be judged by their ability to link forces to enable tactical-level integration. Not all lines of effort or missions demand JADO solutions, so understanding and defining what each distributed C2 node can and should do is vital. This is classic JTF C2—“form follows function” and “get your C2 right up front.”14 The numbered fleets certainly have a consequential role in theater C2, but it may not be in the execution of operational art required to control joint all-domain fires.

A new flexible construct might consist of the numbered fleet commanders managing force apportionment and enablement and directly commanding and controlling Navy missions such as sea control and theater antisubmarine warfare that require joint support but do not rise to the level of full JADO. Offensively oriented task forces and groups likely need direct access to higher echelon forces. Other services have experimented with all-domain operations centers (ADOCs), and these will likely be a focal point for JADO.15 The RAND study Multiple Dilemmas: Challenges and Options for All-Domain Command and Control explores the development of ADOCs at the geographic combatant commands and/or component commands as one potential solution.16

The most prudent recommendation will likely be a combination of distributed control mechanisms that combine both traditional service component and high-end JADO requirements. Creating a web of distributed C2 nodes could connect forces in traditional missions and simultaneously provide disciplined pathways that flatten C2 by linking tactical-level forces to upper echelon capabilities.

Centralized Command

As any Navy officer would attest, authority, accountability, and responsibility rest with the commander. Centralized command should begin with establishing C2 relationships that facilitate joint and all-domain theater enablement and provide access to national and functional combatant command capabilities. Efforts to integrate space and cyber effects into tactical operations must be driven by the geographic combatant commander or JTF commander with an eye on lower echelon C2 capabilities and requirements. Cyber mission teams need to be operationalized to train and conduct preconflict events with the forces likely to need their integration. The hurdles that currently exist between the geographic combatant commanders and effective space and cyber integration almost guarantee these capabilities will not be tactically meaningful. If space and cyber capabilities are not integrated during training, Navy units will not know how to use them in combat.

Geographic combatant commanders are also responsible for the strategy that joint forces must translate into tactical action and theater standards that make such joint actions possible. These standards are created by establishing and enforcing unity across joint operations areas, including fire-support coordination measures, special instructions, datalinks, and technologies such as the Joint Automated Deep Operations Coordination System or its future replacement.

What JADO and JADC2 are missing is a new all-domain “Current Tactical Orders and Doctrine, U.S. Pacific Fleet,” otherwise known as “PAC 10” and originally issued in 1943 to address continued deficiencies in operational and tactical execution. Prior to the war, the Navy had concentrated on developing what was referred to as “major tactics,” with emphasis on coordinated combined-arms attacks on enemy formations by all elements of the fleet. This emphasis came at the expense of what was known as “minor tactics”—leaving squadron and task force commanders to develop combat doctrines and battle plans themselves.17 In “U.S. Navy Surface Battle Doctrine and Victory in the Pacific,” Trent Hone explains that “this mechanism worked well under prewar conditions, when formations were cohesive and had time to drill under individual commanders.” But when ships were thrown together, such as during the naval battles for Guadalcanal in November 1942, “the commanders had no time to develop common doctrine or plans, and the resulting losses were severe.”18 PAC 10 ultimately “provided what the Navy had been missing—a common set of tactical principles for the cooperation of small forces and detached units in battle. It corrected the underemphasis on minor tactics, granting them the same detailed treatment that major actions had received for more than a decade.”19

Despite more than 30 years of deliberate joint effort, the problems PAC 10 addressed in the 1940s not only are still relevant, but also are amplified by the addition of new services, domains, and capabilities. A theater-wide, all-domain PAC 10 must raise its doctrine above that of the fleet and into the realm of JADO and be focused on the details.

New technologies and strategic realities are driving innovation and change at a rapid pace. The dizzying list of new programs and projects—all with flashy names, such as Overmatch, Convergence, and Kessel Run—often result in two distinct but equally deleterious effects. First, they can generate a feeling of being overwhelmed and therefore unable to handle or adapt to the scope of the problem. Second, they may give the false impression that all must be well given the sheer awesomeness of many of these initiatives. The reality lies somewhere in between. Leaders must focus on the fundamentals. Rapid technological innovation and diverse and resilient kill webs can inspire awe, but, ultimately, the many detailed processes and minor tactics will determine each initiative’s success or failure.

1. Summary of the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) Strategy (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, March 2022), 5–7.

2. Department of Defense, Summary JADC2 Strategy.

3. Charles McEnany, “Multi-Domain Task Forces; A Glimpse at the Army of 2035,” Association of the United States Army, 2 March 2022.

4. Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 2017); Department of the Navy, Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) Handbook, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, May 2023); U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR), 11 January 2023; and Rachel S. Cohen, “Here’s the New Marine Corps Strategy for Training Future Troops,” Marine Corps Times, 29 November 2022.

5. U.S. Air Force, Air Force Doctrine Note 1-21: Agile Combat Employment, Curtis E. Lemay Center for Doctrine Development and Education, 23 August 2022, www.doctrine.af.mil/Portals/61/documents/AFDN_1-21/AFDN%201-21%20ACE.pdf.

6. Diana Stancy Correll and Megan Eckstein, “Navy, Marine Corps Test New Naval Integration Concepts in 7th Fleet,” Navy Times, 27 September 2022; and RADM Derek Trinque, USN, “Naval integration in the Western Pacific,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 149, no. 11 (November 2023).

7. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr., USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, 2nd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, December 1999), 314.

8. COL Scott King and MAJ Dennis B. Boykin IV, USA (Ret.), “Distinctly Different Doctrine: Why Multi-Domain Operations Isn’t AirLand Battle 2.0,” Association of the United States Army, 20 February 2019, www.ausa.org/articles/distinctly-different-doctrine-why-multi-domain-operations-isn’t-airland-battle-20.

9. MAJ Robert G. Armfield, USAF, Joint Terminal Attack Controller: Separating Fact from Fiction, research report (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air Command and Staff College, Air University, April 2003).

10. B. A. Friedman, On Operations: Operational Art and Military Disciplines (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, October 2021), 5.

11. Joint Publication 3-32: Command and Control for Joint Maritime Operations (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, August 2008), xiv.

12. CAPT Dale C. Rielage, USN (Ret.), Navy Staff Officer’s Guide (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, November 2022), 231.

13. Joint Chiefs of Staff J7, Insights and Best Practices Focus Paper: JTF C2 and Organization, 2nd ed. (Suffolk, VA: January 2020).

14. Joint Chiefs of Staff J7, JTF C2 and Organization, 4.

15. McEnany, “Multi-Domain Task Forces.”

16. Miranda Priebe et al., Multiple Dilemmas; Challenges and Options for All-Domain Command and Control (Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation, 2020).

17. Trent Hone, “U.S. Navy Surface Battle Doctrine and Victory in the Pacific,” Naval War College Review 62, no. 1 (Winter 2009): 6–9.

18. Hone, “U.S. Navy Surface Battle Doctrine,” 6–9.

19. Hone.