Today, the discourse of national security—its “grammar,” to use Clausewitz’s term—has an unprecedented amount of economic content. Examples abound. “Economic security is national security,” asserts the previous administration’s national security strategy.1 The current administration’s national security strategy sets forth a three-part economic strategy to “outcompete” China.2 In a September 2022 speech, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan stressed the need for the “deep integration of foreign policy and domestic policy” in reference to technological and economic competition.3

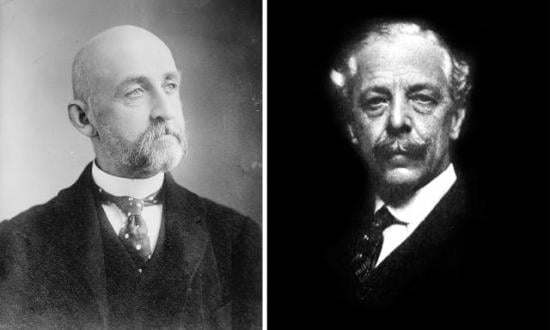

But we are just beginning to grapple with this grammar’s meaning and its implications. To better understand it, we need accompanying strategic narratives, historical analogues, and modes of discourse. The work of U.S. sea power theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840–1914) helps fulfill that need. Mahan is best known for two ideas: Navies must win in decisive and overwhelming fashion against enemy fleets-in-being, and nations must build huge, powerful navies to achieve such victories. These propositions, set forth in The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783, made him the preeminent philosopher-promoter of U.S. naval armament and expansionism, either lionized as a patriotic visionary or reviled as a militarist imperialist and even an instigator of the arms races that led to World War I.4

A certain dose of this critique of Mahan may be justified, but it should not blind us to his insights. For contemporary purposes, Mahan deserves a new reading that emphasizes what may be called his geoeconomic approach to strategy.5

From the outset of The Influence of Sea Power, he describes the sea in decidedly commercial terms. The sea forms lines of travel—trade routes are part of a “great highway” and a “wide common.”6 He is insistent—remarkably so—on focusing on commercial as well as military (or, more precisely, naval) power and on their link to national wealth and prosperity: Trade produces wealth that leads to maritime strength. Naval strength protects trade.7 National wealth, commercial power, and naval power are in fact a dynamic strategic “trinity,” a geoeconomic companion to Clausewitz’s more geopolitically inflected trinity of people, government, and military power.8

Mahan sets forth examples of what may today be called the larger economic, cultural, and technological ecosystem required for control of the seas. His discussion in the opening pages of The Influence of Sea Power draws attention to a series of factors that cluster together to create the technology and institutions capable of producing sea power.

Development of this ecosystem takes time—decades, perhaps even centuries. Mahan describes how England’s long-cultivated trading practice with Portugal, developed over the centuries, is a key reason that kept Portugal from being drawn into an alliance against England during the Seven Years’ War.9 And Mahan reveals how, over the long course of the 17th and 18th centuries, England built a robust naval culture that could withstand inferior admirals and captains.

In the Indian Ocean campaigns during the American Revolution against Admiral Comte Pierre André de Suffren, perhaps the greatest of the French admirals, the English fleet escaped disaster time and time again. While it was only through superior skill and resourcefulness that Suffren was able to keep his fleet sailing, the English got resupplied quickly and with relative ease. Whereas French junior officers lacked Suffren’s zeal and cunning, enough junior English officers overcame their mediocre commanders’ misjudgments.10

A nation’s technological advancement likewise requires an ecosystem that links national wealth with a nation’s commercial and militarized naval power. Mahan’s choice of the multisail ship era as historical epoch reveals a profound technological truth. In the pre-Industrial Revolution era of the 17th and 18th centuries, the supreme example of technological achievement—the essence of “high tech” in its day—was the construction, maintenance, and use of the naval multisail ship. It was an immense, technologically complex effort, involving expert use of raw commodities and precise knowledge to create the anchors, guns, pumps, sails, navigational tools, and countless other parts the ships required. Here England’s technology system provided national advantage—for instance, it produced copper-bottomed ships that were swifter and could more easily overtake their rivals.11

The Influence of Sea Power begins in 1660, at a hinge in modern history. The bloody European confessional wars are largely over following the 1648 Treaty of Augsburg. The formerly dominant Spanish Hapsburg empire is in precipitous and permanent decline following the 1649 Treaty of the Pyrenees. Nation-states engage in global commerce and conflict that, for good or ill, creates the first global supply chain networks as distant colonies send goods from all parts of the world to Europe.

Mahan describes four essential European nation-states at the outset of the era: Spain, Holland, England, and France. Spain’s overextended, overtaxed, and underresourced empire is fading. Holland is still in the front ranks, a remarkable accomplishment given its size. But Mahan detects the fatal flaw that will bring its downfall. Its power is excessively dispersed among commercial interests wholly focused on commercial gain. It is not that the Dutch lack martial courage—as Mahan puts it, a “more heroic people than the Dutch never existed.” The problem is that Holland has failed to accompany its commerce with military power that can sustain it.12

England, on the other hand, has created a commercial–military ecosystem that dates back to Henry VII’s cultivation of a wool economy and trading system. It is perpetuated and strengthened through the establishment of a strong navy during Cromwell’s protectorate and is furthered by his Restoration successors.13

Then there is France. It is in many ways the opposite of Holland: centralized, militarized, and obsessed with European power politics. Exemplified by Louis XIV, France plunges into one war after another, “fixed on the continent.”14 Louis continually seeks “extension by land.” He immerses himself in other nations’ palace intrigues. He calculates how to marry off relatives to create alliances. Either due to his own fears or the anger of his powerful mistress, he forms an alliance with Austria, Russia, Sweden, and Poland against Prussia. All this causes Frederick the Great to launch a preemptive strike into Saxony in 1756, triggering the Seven Years’ War. France “needlessly enter[s] upon another struggle.”15

Mahan points out that Louis should have been expanding his commercial power and increasing France’s already significant wealth. Instead, his obsession with “continental war” obscured the “true character” of the great power conflict. He needed to take control of the sea, the era’s global supply commons, from England. But Louis was too bewitched and bothered by continental politics to listen to his insightful minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert.16 Colbert deftly used economic statecraft via “warfare of tariffs and premiums” to limit Dutch power and influence.17 And Colbert insisted on anchoring France on the “firm foundation of national wealth” by restoring financial order and discipline, by fostering production, and by developing a large merchant shipping fleet supported by a powerful navy. But Louis’ geopolitical obsessions ultimately won out, and French armies fought in near-endless campaigns and battles, some won, some lost, but even the victories Pyrrhic.

France’s travails on the European continent can be seen as a metaphor for unbalanced geopolitical intrigue. It contrasts with England’s more balanced and geoeconomically inflected calculations, with sea power at the strategic center of it all. Of course, Mahan likely overstates the case.18 But in passing him off as “simply” a naval strategist, we miss the geoeconomic underpinnings of his strategy: His emphasis on sea power needs a closer reading. Mahan never argues for militarized naval power for its own sake.

Instead of simply militarized naval power, Mahan says what is needed is sea power. Sea power is, in the context of the 17th and 18th centuries, the nexus of commercial and national military power that creates national wealth. That wealth in turn generates even greater commercial and military power. Mahan’s conception of sea power—national wealth, global commerce, and militarized naval power—can be reimagined in today’s terms as national economic growth, sustainable supply chains, and military power in a continuous, harmonious relationship that requires constant oversight and evaluation. Veering to one side—a pure economic strategy (think Holland)—or the other—an overly geopolitical one (think France)—creates disequilibrium. Commercial plenty without military strength leads to timidity, but military force without economic prudence leads to folly, if not disaster.

While The Influence of Sea Power is undoubtedly Mahan’s most famous and influential work, he develops such geoeconomic themes in numerous other books and essays. For example, in a later influential article, “The Isthmus and Sea Power,” on the possibility of a transisthmian canal, he points out that nations proceed with their own inevitable “commercial logic.” A nation’s geoeconomic behavior is not engrafted mercantilism: Nations, by the “very characteristics which make them what they are,” consequently “are led perforce to desire and to aim at, control of these decisive regions [of trade and commerce].” They do this not only for “bare existence,” but for an “increase of wealth of prosperity.”19

Mahan realizes that contrary to end-of history globalists, nation-states are not simply receptacles of commercial activity but inexorably seek economic expansion and prosperity. In a passage worthy of Mackinder, he writes how a transisthmian canal will fundamentally reorient the commercial epicenter of the globe to create a massive national competitive advantage. With such a canal, even the far eastern coasts of Japan, China, and Australia will then be “nearer to New York than Liverpool”: The planetary commercial axis will shift from Great Britain to the United States.20

Mahan has his flaws. He is often compared unfavorably to the other great sea power strategist, Sir Julian Corbett. Corbett is considered the more sophisticated heir to Clausewitz, a thinker who takes Clausewitz’s On War as a “heuristic point of departure.” Mahan, in contrast, is seen as narrow and “Jominian,” in reference to Antoine-Henri Jomini, the Swiss general who supplies mechanical and context-free rules about warfare.21 And, indeed, Mahan is no Clausewitz. Mahan does lack the political astuteness of either Clausewitz or Corbett. He certainly lacks Clausewitz’s uncanny and intricate descriptions of war in its real and absolute senses, Clausewitz’s notions of war’s grammar and logic, and the Prussian’s brilliant, evocative metaphors.

But, in turn, Clausewitz is no Mahan. Clausewitz writes little to nothing about technology or economics.22 Mahan grasps their relationship in his understanding of the multisail ship of his period of study. He more readily articulates the need for balance among instruments of power. In contrasting England and France, he demonstrates how military and commercial power provide for and protect national prosperity and how excessive “geopolitics” can lead to fruitless, destructive ends. And Mahan explicates how his own “trinity” of wealth, sea commerce, and militarized naval power—what today one could translate as economic growth, global supply chains, and military power—must be sustained in a continuous, harmonious relationship.

In today’s world of especial economic and technological competition, disaggregated and disintegrated global supply chains, and ever-increasing intersection of government and private-sector economic action, Mahan deserves a new reading. We should consider Mahan as both a naval and a geoeconomic strategist, as not only relevant for today, but perhaps even necessary.

1. That phrase, uttered by President Donald Trump in November 2017, is the epigraph of “Pillar II: Promote American Prosperity” of that strategy. See President Donald Trump, National Security Strategy of the United States (Washington, DC: The White House, December 2017), 17.

2. President Joe Biden, National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: The White House, October 2022), 24.

3. See “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at the Special Competitive Studies Project Global Emerging Technologies Summit,” Washington, DC, 16 September 2022.

4. See, e.g., Beatrice Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 224.

5. Of course, Mahan’s economic insights have been appreciated in particular maritime circles. See CAPT H. Kaminer Manship, USN, “Mahan’s Concepts of Sea Power,” Naval War College Review 16, no. 5 (January 1964): 15–29. Manship’s essay remains as timely today as when it was written.

6. CAPT A. T. Mahan, USN, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 (Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace, 13 March 2017), ch. 1 at 16.

7. Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power, ch. 2 at 74.

8. For Clausewitz’s “paradoxical trinity” of “primordial violence,” see Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 89. Innumerable commentators have written on that “trinity.” See, e.g., the essays by Peter Paret (“The Genesis of On War”), Michael Howard (“The Influence of Clausewitz”), and Bernard Brodie (“The Continuing Relevance of On War”) in that same volume. See also Donald Stoker, Clausewitz: His Life and Work (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2014), for a comprehensive contemporary understanding.

9. Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power, ch. 8 at 166.

10. Mahan, ch. 11 at 220 and ch. 12 at 236.

11. Mahan, ch. 5 at 108 and ch. 11 at 212.

12. Mahan, ch. 2 at 54.

13. Mahan, ch. 2 at 55.

14. Mahan, ch. 6 at 129

15. Mahan, ch. 8 at 154.

16. Mahan, ch. 3 at 76.

17. Mahan, ch. 2 at 58.

18. See Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (New York: Vintage, 1987), 96–97.

19. CAPT Alfred T. Mahan, USN, “The Isthmus and Sea Power,” Atlantic, October 1893, 461.

21. Mahan, “The Isthmus and Sea Power,” 466–67. Mahan did write about the military aspects of the canal as well. See Alfred T. Mahan, “The Panama Canal and the Distribution of the Fleet,” North American Review 200 (September 1914): 416–17.

21. Michael I. Handel, “Corbett, Clausewitz and Sun Tzu,” in Masters of War; Classical Strategic Thought, 3rd rev. ed. (London: Cass, 2001), 294–95.

22. Clausewitz discusses it only in book 5, chapter 14, of On War. Entitled “Maintenance and Supply,” it is mostly about how to provide rations for troops.