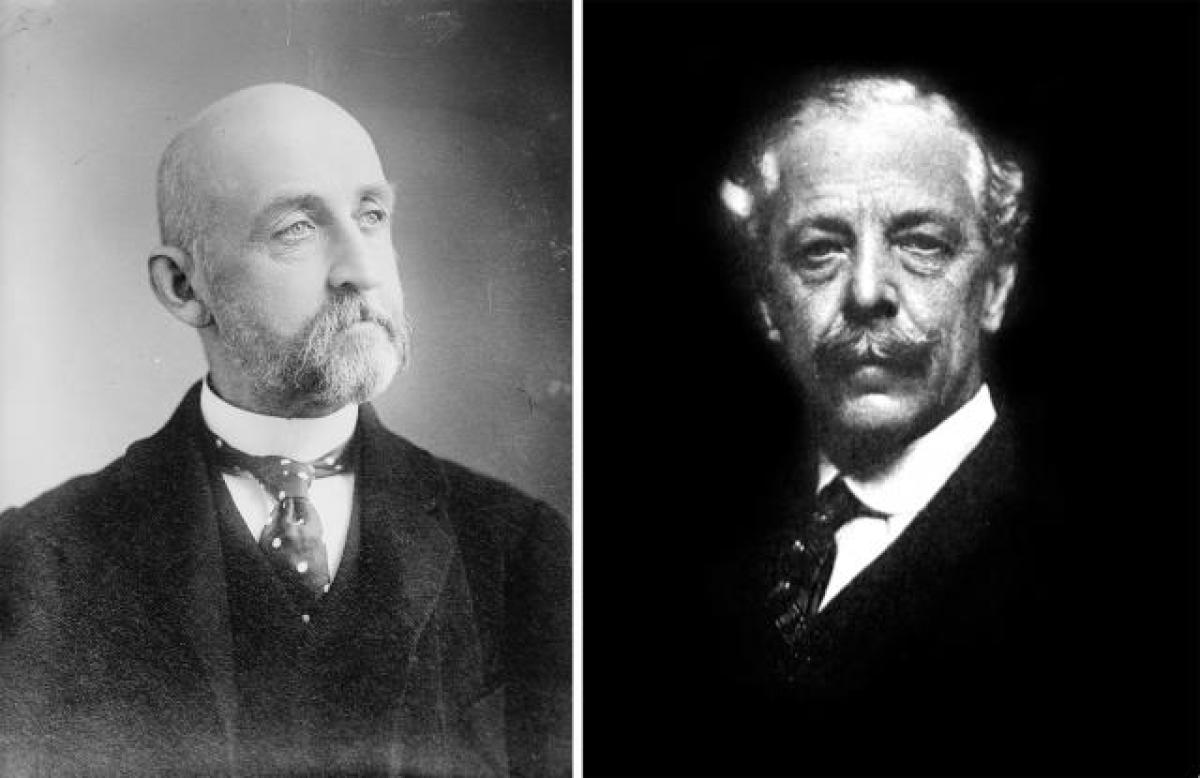

Lieutenant Suarez’s analysis of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s thinking on maritime economic warfare is acute. He gives Mahan proper credit for his understanding of the implications of globalization and the potential of sea power to achieve decisive effects in a new economic paradigm. Suarez also clarifies the point—likewise raised by Nick Lambert—that, however much Mahan advocated the need for decisive victory at sea, he always understood that a successful fleet action was a means and not an end. Dominance at sea allowed domination of the enemy’s trade.

Suarez’s analysis of Sir Julian Corbett is equally fair in relation to Corbett’s views as expounded in 1911 in Some Principles of Maritime Strategy but does not tell the whole story. Corbett’s thinking changed with World War I. Corbett had been focused on limited conflicts; he came to terms with total war. Of the British declaration of the North Sea as a war zone at the beginning of 1915, he wrote: “It was useless to shut our eyes to the fact that the old methods would no longer serve.”1

Although he came from a commercial family, Corbett had not fully comprehended that the guerre de course could no longer be about attacking trade to erode an adversary’s ability to finance war but undermining its economic existence and even its entire national life. Not only had the world become globalized, with intricate international arrangements for finance, but industrialization meant the character of war had changed. The age of mechanized war had begun, and armed forces required vast resources which demanded the mobilization not only of national manpower but national industry. Furthermore, the advent of “just-in-time” economies, notably that of the United Kingdom, had created critical dependencies on the safe passage of raw materials and foodstuffs. Before 1914, the British maintained only a few weeks of grain supplies. If merchant ships were prevented from arriving in British ports, the country would starve.

Corbett also had to steel himself to an economic conflict involving not prize-taking, but death. Even though France’s Jeune Ecole had considered during the 1880s such ideas as using torpedo boats to attack merchant shipping, Corbett had refused to accept that a combatant would “incur the odium of sinking a prize with all hands.”2 In volume II of Naval Operations, the official history of Britain’s naval war, Corbett admitted that “Naval Authorities of the highest distinction [by which he meant ‘Jacky’ Fisher] had foretold before the war that the Germans would not scruple to use the new weapon against merchant ships both belligerent and neutral.”3

The inference is that he had not foreseen this, just as he did not foresee many other developments. But that did not mean Corbett was blind to them when they occurred. Rather, as an acute observer close to the center of the Admiralty’s conduct of the naval war, Corbett watched—and learned. He steeled himself to the new reality and was and remained a forceful advocate for Britain’s right to impose an increasingly stringent blockade on Germany and its allies.

Had Corbett lived long enough to revise Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, it would have become a very different book, saying much less about limited war and more about existential conflict. It would have seen the end of the idea that the maritime domain was inherently and always subordinate to land. It would also have avoided the suggestion that an action had to take place on land for it to have a decisive effect on land, an interpretation that too many modern authorities have placed on one of Corbett’s most famous paragraphs in Some Principles.4

For Corbett’s mature thinking had come to align with that of Mahan’s of years earlier. His journey of understanding between 1914 and 1918 provides insights for 2021. Modern maritime strategists need to recognize, as Lieutenant Suarez states, “the significance and consequences of interdicting commerce,” both in the direct and the multiple-order effects that will follow for an interconnected and highly stressed global economic system. Furthermore, commerce warfare at sea must be understood for the devastating—even existential—effects it may have on the target. It can be a kind of weapon of mass destruction, even when it ostensibly requires no kinetic action—and thus the response from the intended victim might be extreme.

On the other hand, it also may misfire completely, achieving little of significance. Economic warfare, in other words, is rarely clean and never simple. Navies in particular need to do more to understand just how it might work. That requires a much better understanding of the global economic system than may currently reside within any of our joint or naval staffs.

—Rear Admiral James Goldrick, Royal Australian Navy (Retired)

It is an honor to have my thoughts taken so seriously by such an authority as Rear Admiral Goldrick. Yes, we cannot allow Corbett’s and Mahan’s most famous works to define their overall impressions of maritime strategy. My original article was built on a pair of lesser-known articles, one by Mahan and one by Corbett, written in parallel and analyzing the same problem, to make a side-by-side comparison. We both agree that Mahan possessed a far more sophisticated grasp than Corbett of international economics and the implications of globalization for maritime strategy.

Admiral Goldrick argues that, during World War I, Corbett caught up with Mahan’s understanding of a globalized economy and the importance of sea power in disabling an enemy’s economy and that had he lived, he would have rewritten Some Principles. This makes sense. But cannot this be said of Mahan as well? Had he lived longer, would not he also have refined his ideas?

Respectfully, I remain unconvinced that Corbett understood the complexity of a globalized economy to the same degree as Mahan, who spent well over a decade exploring and writing on this subject. I admit that I have not studied Corbett as closely Admiral Goldrick, but the pieces I have read left me wondering: How much did Corbett understand versus how much did he simply hear and repeat? Besides, “coming to terms with total war” is not at all the same thing as understanding the intricacies of globalization. The imperatives of total war required measures that destroyed globalization by fundamentally changing the character of the world economic system. It is not even clear that Corbett understood this change had occurred, or why.

Neither Corbett nor Mahan can solve today’s naval problems because the world is so different. But they can help us to ask the right questions. Because Mahan better understood how the globalized economy worked, he appears more useful in helping us build a framework for understanding sea power in its relation to commerce interdiction.

After much study, I am forced to ask if commerce interdiction even practical today. The U.S. Navy today has no clear understanding of the problem. Simply declaring a “blockade” is wholly insufficient. It is a subject of more complexity than space here allows, but I suggest three main points to serve as a point of departure towards a better understanding.

Scale. Effective commerce interdiction would have to be a massive undertaking. More than 90 percent of global trade by volume transits the ocean, most of which travels in 6 million containers transported in 61,000 ships. This flow of goods depends on a robust flow of digital information.5 The effective attack and defense of sea trade, therefore, encompasses both the physical and virtual worlds.

Information. The physical movement goods and its digital parallels is so great that it must be accurately mapped beforehand. Global trade routes are dynamic and change daily. This requires access to vast amounts of real-time information—ship manifests and property ownership to name two essential requirements. Information is also the first requirement in ensuring compliance for detecting (and deterring) fraud. Not all parties affected by commerce interdiction will comply with Navy directives.

At The Basic School, Marine Corps instructors constantly remind students that the enemy also gets a vote. In maritime war, allies, neutrals, corporations, and citizens across the globe get votes, too. Mahan understood this: “Sea commerce interdiction is more than simply stopping maritime trade, it is an attack on national and global life itself.” As happened in 1914, the multiple-order effects of large-scale commerce interdiction will be felt across the entire globalized economy, and they will likely be devastating. The intricacies of property rights, flagging laws, neutral’s rights, and belligerent’s rights, domestically and internationally, must be understood. The Navy should not assume it will be allowed free reign to interdict as it pleases. This is something today’s Navy must come to terms with.

We are told to prepare for “peer-to-peer” conflict, and that we will “deny enemy objectives, destroy enemy forces, and compel war termination.” But how? History suggests that a sure-fire way to compel the enemy's surrender is to destroy the economic foundations of their state and society. The Navy should listen again to Mahan and remember that the devil is in the details.

— First Lieutenant Matthew Suarez, U.S. Marine Corps

1. Julian S. Corbett Naval Operations, vol. I, To the Battle of the Falklands December 1914 (London: Longmans Green, 1920), 179.

2. Julian S. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 269.

3. Julian S. Corbett Naval Operations, vol. II, 132.

4. “Since men live upon the land and not upon the sea, great issues between nations at war have always been decided—except in the rarest cases—either by what your army can do against your enemy’s territory and national life or else by the fear of what the fleet makes it possible for your army to do.” Corbett, Some Principles, 16.

5. Stephen M. Carmel, “Globalization, Security, and Economic Well-Being,” Naval War College Review 66, no. 1 (Winter 2013): 45.