On 14 March 2023, the Colombian Navy seized a drug cartel semisubmersible carrying 5,800 pounds of cocaine to an unknown destination in the Pacific. The year before, authorities captured a similar 50-foot narco-sub carrying 8,000 pounds of cocaine. Thirty years of trial, error, and innovation have refined a comprehensive maritime covert supply chain for cocaine cartels along South America’s coast. The United States and its Pacific allies should consider adopting these tactics to support a sustained Taiwanese resistance in a potential conflict.

No ‘Ukraine model’ for Taiwan

“There is no ‘Ukraine model’ for Taiwan,” the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) concluded after running wargaming scenarios on a future war between the United States and China over Taiwan. According to the report, while the United States and its allies prevailed over China, “defense came at high cost. The United States and its allies lost dozens of ships, hundreds of aircraft, and tens of thousands of service members.” One of the key takeaways was China’s ability to “isolate the island for weeks or even months.” In Ukraine, a 332-miles land border with Poland has made sustainment of conventional combat possible. In Taiwan, geography dictates that this model cannot be replicated.

Preparing Taiwan to step up in a conventional fight is feasible for delaying China, but impossible for sustained combat. CSIS wargaming estimates a maximum of two to three months before Taiwan faces serious ammunition shortages. In the event of a prolonged war, Taiwan must prepare to wage an asymmetric war of resistance on the island. Meanwhile, the United States must prepare to support the island when air and sea dominance cannot be guaranteed.

Narco-Submarines: Necessity’s Invention

The narco-sub fleet was developed to replace the cocaine speed boats of the 1980s and 1990s, trading speed for stealth as a consequence of the Coast Guard’s upgrades in radar and interception capabilities. The first reported discovery of a narco-submarine came in 1988 after a 21-foot coffin-like vessel washed ashore in Boca Raton, Florida. Cartels specializing in cocaine have since developed several variants of fully and semisubmersible ships to deliver products overseas covertly.

Cocaine submarines typically follow three basic forms, with minor upgrades and variations. Low profile vessels (LPV) are semisubmersible craft in a variety of sizes with either an outboard motor (LPV-OM) for high speed or an inboard motor (LPV-IM) for stealth, with only a small cabin and the exhaust visible above the waterline. These are the most interdicted trafficking vessels.

Fully submersible vessels (FSV) are just what they sound like. To date, no FSV has been interdicted at sea, though several have been found in rivers. Limitations in oxygen and technology restrict FSVs from operating below 20–30 meters and they are not usually fully submerged for the entire voyage.

The third form is the narco-torpedo towed from vessels or discreetly attached to the outside hull of cargo ships. Narco-torpedoes are uncrewed and collected by couriers once they reach a coordinated pickup point—sometimes just offshore.

Automating semisubmersibles with a combination of GPS and basic programming does not incur significant costs. Even the most sophisticated narco-submarines are estimated to cost approximately $2 million. Despite these modest origins, in 2022 authorities seized a 72-foot LPV that traveled 3,920 nautical miles across the Atlantic from Colombia to Spain carrying three tons of cocaine.

Supply-Sub Characteristics

Calls for the U.S. Marine Corps to adopt narco-submarines in the Pacific to support expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) are gradually making their way into doctrine. Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 4: Logistics specifically addresses adopting drug cartel tactics and integrating them into covert and hybrid logistics programs. Adopting similar vessels and tactics not only would keep Marines sustained in contested environments, but also could support Taiwan in the face of a Chinese blockade.

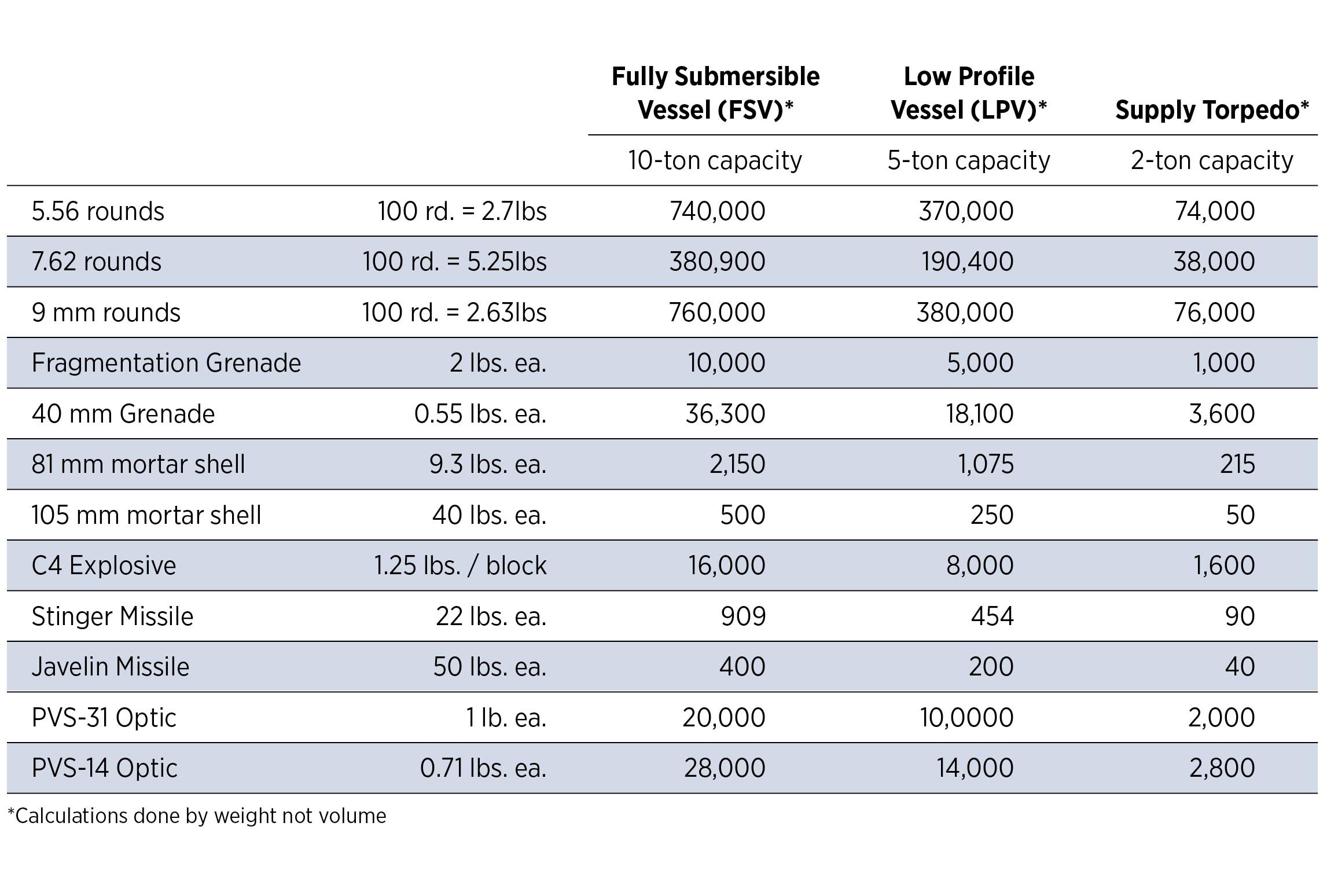

Development should follow the three models currently used by cocaine smugglers: a heavy-lift (ten-ton capacity) FSV, a medium-lift (five-ton capacity) LPV, and a light-lift (two-ton capacity) torpedo module. All variants should be unmanned and use automated internal software to reach their destination. Removing a manned pilot optimizes space for cargo, sensors, fuel, and propulsion while keeping sailors and Marines out of harm’s way. Internal systems navigating pre-programed routes would limit the vessel’s electronic signature. Passive sonar combined with autonomous vessel avoidance software would allow the submersibles to identify and circumvent any traffic on its route.

Following similar narco-sub designs, an FSV would need to be only 70 to 80 feet in length. Because FSVs do not need to submerge to extreme depths, hull construction can use lighter and less expensive material than ordinary subs. Basing LPV designs on cartel equivalents suggest they would need to be roughly 50 feet in length to carry five tons. As a semisubmersible, it can continually receive GPS signals at the surface for its internal guidance system. A torpedo module would consist of a propulsion and guidance module fitted to a cylindrical cargo tube. The module would guide the torpedo to shore and beach itself where a beach party can collect the supplies and then scuttle the module and container. Such a vessel would encourage commanders to accept higher levels of risk for delivering supplies, knowing that the smaller and cheaper torpedo module would not need to return.

Supply-Sub Employment

In the event of a Taiwan conflict, these vessels could launch from either the well deck of an offshore dock landing ship (LSD), landing platform dock (LPD) vessel, or even from ports in Guam, Okinawa, or the Philippines. The sub would then navigate to a set of coordinates along Taiwan’s eastern shoreline. The deep waters off Taiwan’s eastern coast would allow more space for FSVs to evade blockading ships.

Encrypted messages to forces on shore would share the arrival time and location data for delivery. At the time of intercept, the vessel would intentionally beach itself so local forces could offload the supplies before pushing the vessels back out to sea. By timing the deliveries with the tides, forces ashore could easily get a supply-sub back underway after offloading.

Back at sea, the onboard autopilot would then initiate a return-to-base or return-to-coordinates for an at-sea pickup. Taiwan’s roughly 320-kilometer eastern coast provides the cover of deeper waters, and its flat sandy shores butt-up against steep mountainous terrain where resistance fighters can take refuge after offloading weapons and equipment. Intermediate supply depots deep within Yushan and Shei-Pa National Parks could then distribute equipment to units engaged in fighting on the more populated western side.

Supply-Sub Capacity

Covert logistics alone would not provide the level of large-scale support needed to sustain a conventional war. The objective would not be to defeat the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in conventional combat. Instead, these methods would aim to sustain resistance fighting akin to the support provided to the Mujahideen during the 1980s that wore down the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Adopting them would mean arming and supporting a durable resistance. Forces on the island would need to keep the area contested either until an international coalition from the outside can push China back, or fighting on the island becomes too costly for China to sustain.

Repair parts for military equipment and ammunition for larger artillery pieces could be shipped initially, but in the event of prolonged conflict these conventional assets would inevitably be destroyed or captured. Small arms and ammunition, along with portable surface to air missiles and other small-unit level supplies, would be the primary materiel for military-adapted narco-subs.

To estimate the requirements for supporting a Taiwanese resistance using supply-subs, an estimated baseline of support must first be established. A CH-53, the heavy-lift helicopter for the U.S. Marine Corps, is capable of carrying 18 tons. Alternatively, the MV-22 Osprey, the Marine Corps’ multimission tilt-rotor helicopter, can carry 10 tons in the cabin and 7.5 tons via sling-load (17.5 tons total). A Marine expeditionary unit (MEU) of 2,200 troops is typically supported by four CH-53 and 12 MV-22 aircraft. With these, a MEU is expected to sustain itself for 15 days before resupply. Using some simple math, this comes to 142 tons for 2,200 troops for 15 days of sustainment. By dividing that by troop count, the Marine Corps expects on average to provide 129 pounds per Marine every 15 days. Rounding down to 100 pounds to keep things simple, an LPV (five ton) variant could provide 100 fighters with 100 pounds of supplies each per delivery.

Using the same methodology, an insurgent force of 80,000 strong would need approximately 400 tons of supplies every 15 days. This is beyond what supply-subs alone could support. It would take five successful FSV deliveries a week to support just 2,000 fighters at 100 pounds each. However, the numbers improve when factoring for locally sourced food, water, and fuel. Furthermore, throttling the intensity of the conflict, resistance forces could limit the volume of material expenditure. By focusing on critical items such as weapons and ammunition, supply-subs could punch above their capacity.

Based on weight, a single five-ton LPV is capable of shipping approximately 370,000 rounds of 5.56 NATO ammunition—enough to outfit 1,700 troops with a 210 round standard load-out. A 10-ton capacity FSV can ship the weight of 400 javelin missile systems, 900 Stinger (surface to air) missile reloads, or 570 Stinger launcher systems. To date, the United States has delivered 1,400 Singer missiles to Ukraine. In only a few deliveries, the United States could easily match this level of support in defense of Taiwan. See Figure 1.

For decades, the United States enjoyed operating with uncontested logistics. Even when supporting Ukraine against Russia, Western supply lines face little resistance. There are no indications that this will be the case in a struggle over Taiwan. According to experts, China’s strategy for taking the island involves a multilayered blockade to isolate Taiwan. Covert supply subs could provide consistent support to resistance forces. This would give allies flexibility in how, when, and where to respond, opening options for a U.S. response to limit the costs in blood and treasure.