“I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant.”

—Attributed to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Imperial Japanese Navy

Although Admiral Yamamoto never actually uttered those words, he should have.2 In the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora!, the version of Yamamoto portrayed by actor Sô Yamamura makes the statement to reflect his fear of U.S. industrial might. In the 1940s, that capacity was indeed vast.

No longer. In the decades prior to the 2026 scenario, the United States had eviscerated its naval shipyards. During World War II, the nation had more than 50 shipyards that could contribute to the war effort. By 2023, it had fewer than 20—all old. In fact, in the years leading up to the war, China had created significantly more shipbuilding capacity than the United States.3 So as the war began, on the matter of industrial might, China had the substantial advantage.

The U.S. Navy prides itself on having the most capable ships in the world. Unfortunately, the battle coastline in this war is more than 5,000 miles long. Hence, numbers count. Regarding the numbers of ships and the ability to endure attrition, the advantage again went to China.

Before the war, only one of the two main belligerents had been incorporating lessons from the last great Pacific war. This battle is not a repeat of Midway. It is Okinawa in reverse, with the United States on the defending side and China attacking with ten times the size of the landing force that went ashore on Okinawa.4 So regarding the principle of mass, advantage: China.

This does not mean the war thus far has been easy for China—or that the continuation will be. Taiwan has half a million entrenched troops. Intangibles make this fight difficult to handicap, but the odds are not in the United States’—or Taiwan’s—favor.

On the brink of the crisis, U.S. political leaders considered the movement of large numbers of aircraft carriers and surface forces to be unacceptably “visible and provocative.” Combined with the sentiment in some circles that China was merely bluffing to put pressure on Taiwan, the preparatory deployment of most naval forces was withheld. This internal debate made the Chinese more inclined to initiate their attack before the U.S. military could be ready to react decisively.

But one U.S. force has been impactful: submarines. Not “undersea warfare” writ large. Not unmanned undersea vessels, not mine warfare, not distributed sensors, not seabed warfare or any of the other buzzwords that have taken hold of the undersea warfare discussion. In this war so far, none of that has mattered.

What has mattered is manned, armed, lethal, nuclear-powered fast-attack submarines (SSNs). Not only are submarines the only force that has been able to substantially interrupt the cross-strait invasion, but the surge of submarine forces was not visible, not provocative, and therefore was undertaken prior to the opening of hostilities.

And yet, because of the limited number of submarines available during the first month of combat, even that fight has not gone well.

Submarine Missions

Stemming the Chinese invasion of Taiwan demanded antisurface warfare (ASuW) operations, using submarines and aircraft, and antiair warfare (AAW) operations, using aircraft and Taiwan-based air-defense systems.

The main Chinese avenue of attack was along the southern Taiwan Strait shoal, taking advantage of the shallow waters that constricted U.S. and allied attack submarines. Because SSNs are the primary force capable of conducting ASuW in denied areas, ASuW has been their highest priority. The shallow water of the Taiwan Strait (averaging 150 to 300 feet but in some areas just 60 feet) made this a high-risk mission, but SSN operations have been effective. Once detected by Chinese forces, however, the SSNs have found it challenging to escape. To enhance stealth, torpedo attacks have been preferred over Harpoon missile attacks.

The next highest priority has been to protect the flanks and sink People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) surface and submarine forces guarding the approaches to Taiwan. For this mission, joint and allied forces have relied primarily on aviation assets to provide both antisubmarine warfare (ASW) and ASuW coverage.

Submarines were one of the few forces that could penetrate denied areas inside the exclusion zone declared by China. Prior to hostilities, a request from Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, for U.S. submarines to lay mines in the Taiwan Strait was denied by the National Command Authority. With only four SSNs available in the joint operations area at the start of the war, ASuW torpedo attacks were deemed higher priority than mine-laying operations, so no mines were laid by the submarine force. (See “Mine Warfare Could Be Key,” pp. 46–51.)

PLAN submarines predominantly threaten U.S. and allied surface naval forces operating far from the Taiwan Strait, and organic U.S. and allied submarine ASW detection ranges are limited. Therefore, defensive ASW primarily has been a mission for maritime patrol aircraft, surveillance towed-array sensor system ships, SH-60R helicopters, and surface combatants equipped with towed-array and hull-mounted sonar systems.

Submarines armed with Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles (TLAMs) are capable strike warfare platforms. Operating in denied areas, however, SSNs have abstained from this mission because launching TLAMs reveals their location. Hence, sub-launched TLAM strikes have been conducted only by guided-missile submarines (SSGNs) operating at a distance from Chinese threats.

About a third of PLAN submarines have deployed out of area to threaten Japan, Guam, Hawaii, the U.S. mainland, and the Panama Canal. Hunting these submarines has been a job for Navy P-8 aircraft, destroyers, and cruisers with attached MH-60R helicopters, the Coast Guard (with little ASW capability), and pick-up missions by Army helicopters and bomb-laden Air National Guard fighters using radar and visual detection methods. Chile and Canada’s navies have been asked to assist.

Only Los Angeles–class submarines’ torpedo tubes are configured to fire Harpoon missiles, and every Harpoon loaded was one fewer torpedo that could be carried, which limited a boat’s close-in ASuW capability. The capability to launch Harpoons from Virginia–class boats’ torpedo tubes or from vertical-launch tubes in either Virginia– or Los Angeles–class submarines had not yet been developed.

The joint task force commander directed Navy and Air Force aircraft also to conduct cross-strait ASuW, creating a multidimensional threat to PLAN ships, giving them more to worry about than SSNs. Unfortunately, the ongoing battle for air superiority over Taiwan limited the degree to which aircraft could conduct these missions.

Before the war, two submarine operational approaches were considered to thwart the PLAN cross-strait invasion: a “rush-the-passer” approach, in which many SSNs would be surged to try to defeat the initial attack; and a “sustainment” approach, in which SSN deployments would be phased and thus could be sustained for a long-duration fight.

Under the “rush-the-passer” approach, a lengthy rearming and reset period would be required after the initial surge had expended its available weapons, leaving very few SSNs in theater. Under the “sustainment” approach, the small number of SSNs that could be maintained on station likely would not have a major impact on China’s initial landings. For these reasons, leaders selected a hybrid approach: a limited initial surge followed by a reduced sustainment.

Patrol Duration

In World War II, because of the vast search area, slow submarine transit speeds, and lack of target density, submarine patrols sometimes lasted as long as a month. In this war, the target density has been richer, submarine transit speeds faster, and weapons expended quickly, so on average SSNs have found themselves out of weapons within two weeks of arriving on station, at which point they have been directed to transit to reload sites. In all, this calls for a faster operational tempo than the submarine force sustained in World War II.

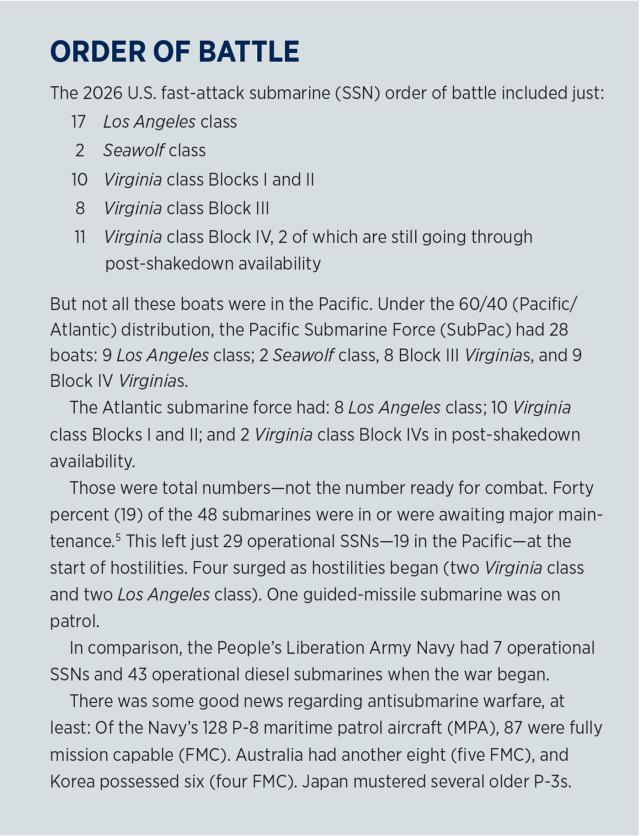

The operational employment of SSNs can be determined using either a requirements-based approach, or an inventory-based approach.6 With an insufficient number of SSNs to allow a requirements-based approach, the only option was one based on inventory. Nineteen operational SSNs in the Pacific (two were held in reserve, one each at Pearl Harbor and San Diego), with a cycle time of 25 percent, allowed just four to be maintained on station.

Some SSNs were rotated to the Pacific during month two, which brought the number of operational SSNs to 23. This yielded 5 to 6 boats on station at any one time.

Battle of the Taiwan Strait

The PLAN deployed landing-force troop ships and other support ships out of nontraditional ports, and it mobilized other ships as feints to saturate detection systems. Because China declared an exclusion zone for the Taiwan Strait at the beginning of hostilities, any ships in the strait were presumed to be supporting the Chinese invasion and, thus, legitimate targets.

On the first day of hostilities, the U.S. Navy deployed four SSNs: two Virginia class from Pearl Harbor and two Los Angeles class from Guam in/around the Taiwan Strait, and one SSGN at standoff distance southeast of Taiwan.

Using the modified sustainment approach, Commander, SubPac, surged one additional Los Angeles from Guam (arrived week two), one additional Virginia from Pearl Harbor (arrived week three), one additional Seawolf from Bangor (arrived week three), one additional Virginia from San Diego (arrived week four), and one additional SSGN (the only other SSGN in inventory) from Bangor (arrived week three).

In addition, four submarines surged from the Atlantic: two Virginia class from Groton, Connecticut, to arrive week nine; and two Los Angeles class from Norfolk to arrive week ten.

The four SSNs on station at the commencement were out of weapons by the end of week two, reporting 53 enemy ships sunk, including two of the three PLAN aircraft carriers supporting air operations over Taiwan, and two of the four PLAN amphibious assault ships.

The on-station SSGN was out of weapons by the end of week one, having launched all 154 TLAMs, primarily at PLAN preinvasion targets.

A Los Angeles and a Virginia were directed to remain on station for surveillance pending arrival of the surge boats, while the two other SSNs returned to port for reload.

All reloads occurred at one of the two remote submarine tender sites. The transit distance to the submarine tender USS Emory S. Land (AS-39) was approximately 1,100 nautical miles—a six-day round trip plus a day to reload per SSN and five days to reload per SSGN. The transit to the USS Frank Cable (AS-40) was an approximately 1,600-nautical-mile, eight-day round trip. The reloaded SSGN was back on station in week five. (Both tenders are now close to 50 years old and struggled to keep up with the pace of operations.)

Picket lines of PLAN Type 054 Jiangkai-class ASW frigates at the northern and southern entrances to the Taiwan Strait increased the transit time for boats that were not already on station when hostilities began. To the extent possible, submarines preserved torpedoes to interdict invasion shipping rather than PLAN ASW assets.

Substantial shallow-water reverberation made PLAN active sonar use in the Taiwan Strait ineffective—yielding many false targets, saturating the PLAN ASW response. Similarly, the high levels of background noise rendered passive acoustic detection of SSNs impossible. Hence, the PLAN’s most effective tactic was visual detection followed by prosecution using ASW helicopters or non-ASW aircraft dropping laser-guided and dumb bombs. A PLA aircraft stumbled on a Virginia-class submarine retrograding for reload. A helicopter from a Type 054 frigate sank it.

During week three, a Los Angeles–class boat was sunk while transiting from Guam to station, reducing the count of available SSNs to 13.

Mid-month, the Navy was directed to pull as many submarines out of maintenance as possible to return them to combat capability, using maintenance waivers as necessary. Naval Sea Systems Command began to review the quickest way to button up work for the 18 submarines in maintenance, prioritizing those without hull cuts. This yielded six additional submarines that could be restored to service, four of which were in the Atlantic. But the earliest any of those could be ready for operations was four months.

Late in week three, China severed the Pacific Light Cable Network underwater cable system (owned by U.S. company SUBCOM) running from Taiwan to the United States, substantially reducing communications with Taiwan. Communication cables owned/operated by Chinese companies were not affected. While SUBCOM had the capability to repair the cable, it elected not to do so during hostilities, which forced the routing of traffic onto cables controlled by Beijing.

Thus far in the war, unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) have not lived up to their promise because of insufficient inventory, limited range, and inappropriate payload. Submarine-launched UUVs have been used as sacrificial mine-detonation devices. So, rather than taking up weapons storage space in submarine torpedo rooms, most sub-launched UUVs have been left ashore. Other heavy, self-deploying, long-range UUVs have been somewhat effective for surveillance and intelligence gathering, but because of the distances involved, the fact that they were relatively easily detected and sunk, and the limited inventory at the start of the conflict, their contribution has been marginal.

Littoral combat ships (LCSs) have been of no value in the ASW/ASuW portion of this fight. Their limited range prevents them being used as escort ships, and they cannot protect themselves in high-risk areas. Although the mine-warfare module is quasi-operational, none of the LCSs could get close enough to active mine areas to use it.

Weapons Inventory

The U.S. inventory of submarine weapons is not publicly available information, but the expenditure rate of those weapons is metered by the number of submarines on-station.7

Torpedoes and Harpoons

Because submarine-launched Harpoon missile production only began in the late 2010s, the inventory was limited such that each Los Angeles–class SSN could initially receive only four. This left space in the torpedo room for 20 Mk 48 AdCap torpedoes per boat. The Virginia and Seawolf classes, which lack Harpoon capability, can carry 24 and 50 Mk 48 each, respectively.

With each SSN expending 20 to 50 torpedoes (and 4 Harpoons per Los Angeles) in a two-week rotation, consumption rates were 60 to 120 heavyweight torpedoes and 8–12 Harpoons per week. With more than 500 weapons available in the initial load, there were enough for one to two months of combat operations.

TLAMs

SSGNs could expend up to 154 TLAMs in the first and third week, with zero expenditures for three weeks until the first reloaded SSGN arrived back on station. With SSNs offloading 12 missiles each, 516 TLAMs were available for SSGN reloads. Each required 154 TLAMs per reload, hence SSGNs consumed the entire inventory of sub-launched TLAMs in only two cycles.

ASW

Similarly, the Navy’s inventory of P-8 sonobuoys was projected to be expended by the end of month four. Based on lessons from “chasing ghosts” during the Falklands War, the P-8 inventory of Mark 54 torpedoes would probably be expended even faster than the sonobuoys.

Presuming the Chinese understand the above, their strategy will involve extending combat operations until U.S. ASW weapons are expended, at least beyond month six.

What To Do Now

For decades, Navy munitions requirements analysis has confirmed that torpedo inventories are insufficient. While it will take years to grow the submarine inventory, the Navy can correct the weapons and sensor shortfall more quickly. It is a “feed and bleed” problem. Either have sufficient inventory on hand or ensure production can be increased quickly to support expected consumption rates. Yet, it has taken five years to restart heavyweight torpedo production, and only a few dozen weapons have since been produced, so this continues to be a major problem.8

Just as there has been an unofficial one-third, one-third, one-third Department of Defense funding split between the Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, within the Department of Navy there has been an unofficial and artificial “fair share” restriction on investment divorced from combat requirements. Instead, investments must be prioritized for the capabilities that will do the most good for the highest priority conflict.

For decades, hunting adversary submarines has been the primary focus of the U.S. submarine force. To prepare for this war, however, the submarine force must prioritize antisurface warfare. Top priorities should be antiship torpedo attacks in a shallow and congested environment, and long-range antiship missiles—potentially even ballistic ones—and better seekers and survivability than the Tomahawk antiship cruise missile.

“Undersea,” like “air” and “space,” is a place, not a mission. When the Navy created the concept of undersea warfare, it diluted the real warfare areas, notably ASW and ASuW. ASW proficiency was then further diluted when the Navy added mine warfare to Fleet Antisubmarine Warfare Command and transformed it into Naval Mine and Anti-Submarine Warfare Command despite the fact that mine warfare and ASW have little in common. Then, other warfare areas were added to create Undersea Warfare Development Command, later Undersea Warfare Development Center. Lost in all this was a necessary focus on the primary mission for U.S. attack submarines in the coming war: ASuW. The Navy must get back to core warfare areas, notably ASW and ASuW.

In this fight, ASW will be mostly defensive and at long range from Taiwan, areas where SSNs likely will not be deployed. Hence, defensive ASW needs to be its own discipline, using maritime patrol aircraft and MH-60R helicopters, not SSNs. The maritime patrol community should drop the “reconnaissance” mission it picked up during the global war on terrorism and revert to an ASW-centric construct.

The High-Altitude Anti-Submarine Warfare Weapon Capability (HAAWC) torpedo program, which converts Mk 54 lightweight torpedoes for launch from P-8s at cruise altitudes, began in 2023. If the war begins in 2026, inventory will be nowhere near required levels without a significant increase in the production rate.9

Finally, the Navy must ruthlessly prioritize certain acquisition programs. The immediacy of this potential conflict demands that, of the three program tradeoff variables—cost, performance, and schedule—schedule must be given top priority for the programs that will make the most difference. Submarine production must be accelerated. Submarines currently in maintenance must be made whole as quickly as possible. And production of ASW and ASuW weapons and sonobuoys should be accelerated to the maximum rates possible. If the Navy does not adjust to this reality, it will lose many lives in this war.

1. William F. Halsey and Joseph Bryan, Admiral Halsey’s Story (Whittlesey House, 1947), 69.

2. It was the invention of the screenwriter of Richard Fleischer’s 1970 film, Tora! Tora! Tora!.

3. Brad Lendon and Haley Britzky, “U.S. Can’t Keep Up with China’s Warship Building, Navy Secretary Says,” CNN, 22 February 2023.

4. The United States landed about 60,000 troops on Okinawa. China currently fields an army of two million, many of whom would be devoted to any effort to take Taiwan by force.

5. Oren Lieberman, “Nearly 40 percent of U.S. Attack Submarines in or Awaiting Repair as Shipyards Face Worker Shortages, Supply Chain Issues,” CNN, 12 July 2023.

6. To complete the ASuW plan by counting on-station required locations, the requirement would be for 12 SSNs to remain on station at a time. Due to weapons expenditure, it is likely that each SSN would be out of weapons within two weeks of arriving on station. Using a cycle time of 25 percent (a quarter of the time on station, a quarter transiting to station, a quarter in restock/reload/emergency maintenance, a quarter transiting from station), the minimum number of SSNs to maintain 12 on-station submarines would be 48 in the Pacific. Unfortunately, the U.S. Navy currently does not have 48 operational submarines globally, let alone in the Pacific, so even excluding all other missions, the ASuW mission cannot be met by the current inventory.

7. This analysis assumes that most of the SSN TLAMs would be backhauled for use by SSGNs.

8. Richard Burgess, “Rear Adm. Perry: First New-Production Mark 48 Torpedoes Set for 2022,” Seapower, 18 November 2021.

9. “U.S. Navy To Get Launch Equipment for Converting Torpedoes into High-Altitude Long-Range Weapons from Boeing,” Marine Insight, 28 June 2023.