The U.S. Navy faces many challenges as it sails deeper into the 21st century, but perhaps none more compelling than the need to communicate to the American people what it must accomplish, how it will do so, and with what assets. In short, it needs an organizational strategy.

Official defense guidance in Washington now has coalesced around China being the “pacing threat” facing the United States and its partners, thereby clarifying the focus of the strategic challenge.1 Yet it remains up to the Navy to design and communicate a simple and persuasive rationale on which to base its operational planning, force design, budget requests, and public communications.

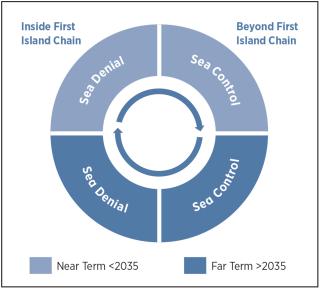

Perhaps the best way to meet that goal is to adopt a concise four-campaign construct centered on deterring conflict inside the first island chain—especially over Taiwan—while strengthening support for U.S. allies and partners on the periphery of Asia and beyond. Adopting such a strategy would yield four lines of effort aimed at:

• Sea denial in the near term to deter conflict inside the first island chain.

• Sea denial deeper into the future to deter conflict inside the first island chain.

• Sea control in the near term to strengthen alliance assurance and strategic access to and beyond the first island chain.

• Sea control beyond 2035 to sustain alliance assurance.

Implementing this strategic approach would raise the bar on deterrence in the near and far term, temporally and geographically. Ideally, it would do so by placing sufficient doubt in the minds of Chinese leaders to prevent conflict. This construct also could serve as a guide for U.S. Navy organizational innovation, spurring the integration of cutting-edge technologies while prompting timely structural reforms.

Why Deterrence?

Armed conflict with China—a nuclear weapons–armed state with more than a billion citizens and the world’s largest industrial capacity—could rapidly escalate to global thermonuclear war, inflicting death and destruction on a scale never seen in the history of warfare. This likely would include massive devastation inside multiple countries, including the United States, while imposing immense, lasting ecological damage around the world. Fighting such a conflict in the traditional manner would be highly risky. Hence, a broad campaign of strategic deterrence, sustained over time, should be the goal of the design and application of U.S. national power in the decades ahead, amplified by the efforts of the many U.S. allies and partners. The United States is blessed to have such partners, the result of decades of tireless diplomacy and farsighted statecraft reaching back to World War II.

U.S. efforts to buttress deterrence will continue to rest on the tense yet functional status of Taiwan today. Indeed, the very imperfection of the current arrangement from both Taiwan’s and China’s perspectives attests to it being the best option available, shrouded in sufficient diplomatic nuance to satisfy the minimal demands of both groups. For China, Taiwan’s formal independence remains off the table. And Beijing’s stated belief in the eventual triumph of its political ideology theoretically puts time on its side. For Taiwan, reintegration with the mainland is pushed off to another day, when it may be considered under better circumstances. Meanwhile, Taiwan survives as a prosperous democracy of 23 million people in the shadow of its vastly larger and more powerful neighbor.

The relative trend of maritime power between the United States and China also underlines the advantage of extending deterrence into the future. U.S. naval power is struggling through a period of structural renewal, as ships and aircraft brought into the fleet under the Reagan buildup exit the force, to be replaced by a new generation of systems and platforms in the decades ahead. Between here and there, however, lies a dangerous trough in numbers, best exemplified by the submarine force. In 1987, the U.S. Navy boasted 97 nuclear-powered fast-attack submarines, the apex predator of warships. Today, it has only 53 fast-attack submarines to accomplish critical missions around the globe, and that number may contract further in the years ahead.

So, how should U.S. policymakers strengthen deterrence, if not solely by threatening the application of military power? President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a master military, diplomatic, and political strategist, reportedly had an axiom, “Whenever I run into a problem I can’t solve, I always make it bigger. . . . If I make it big enough, I can begin to see the outlines of a solution.” Regarding strengthening deterrence, that would mean invoking the full arsenal of U.S. and partner economic, military, and technological power, including threatening to close off market and resource access for China. Doing so would hold at significant risk the economic prosperity that is the foundation of Communist Party legitimacy in mainland China. As Jude Blanchette and Ryan Hass put it in a 2023 Foreign Affairs article, “Ultimately, . . . Washington faces a strategic problem with a defense component, not a military problem with a military solution.”2 Therefore, the U.S. Navy does not need to solve this problem by itself.

Sea Control and Sea Denial

The goals of naval power are to command the surface of the sea (sea control) or deny such control (sea denial). For it is only on the ocean’s surface that mass amounts of goods, fuels, foods, and supplies may be transported economically. Forward presence, power projection, strategic sealift, and other forms of military activity play important roles in achieving and exploiting sea control or sea denial, but they are not ends in themselves.

Of the two objectives, sea control is the apogee of naval power, allowing a nation to command the seas at the time and place it chooses for any purpose. This generally results from projecting power ashore, imposing blockades, and/or sustaining partners’ and its own economy via seaborne trade, which comprises more than 80 percent of global trade today, measured by volume.

In some places, however, adversary capabilities may render sea control prohibitively costly, if it is achievable at all. The Taiwan Strait and other waters adjacent to mainland China meet that definition. Overlayed by persistent, layered surveillance systems integrated in redundant command-and-control hierarchies coupled with a lethal array of land-, sea-, and air-based precision fires systems, the waters peripheral to China increasingly pose deadly threats to foreign forces.

Fortunately, as status quo powers dedicated to protecting the codified norms of the international system (most of which having been agreed to by China), the United States and its partners do not need to establish sea control in such contested waters. Rather, it is enough that they prevent China from doing so via sea denial. Successfully imposing sea denial would, in effect, render such sea space no man’s land, the ultimate no-go space for both sides. While not ideal, such a situation ultimately serves the United States’ strategic ends.

Beyond such highly contested waters, however, it is imperative the United States and its partners maintain sea control. With the premier global economy—and leading a politically and economically integrated alliance of nations in a de facto sea power coalition—the United States depends on sea control for national survival and to sustain and project unified alliance military power.

So, what would achieving sea denial and sea control in the near and far terms look like in detail?

Four Naval Campaigns

Sea denial in the near term. Since the U.S. fleet a decade from now will largely be the same as it is today, deterrence via sea denial must be accomplished through operational innovation, partner cooperation, and effective strategic communications. Ideally, a meshed, continually shifting network of sensors would be irregularly deployed inside the first island chain to provide early warning and help undermine China’s confidence in its ability to conduct a blinding campaign at the outset of conflict. Uncrewed air, surface, and subsurface vessels—increasingly augmented with artificial intelligence (AI) to guide navigation, maneuver, and mission execution—could help with this task, given rapid resourcing from the Department of Defense. The technology is promising. It is time to accelerate testing and delivery.

To further enhance deterrence, a robust multinational surface and submarine presence should be maintained in those same waters, appearing at random times. Indirectly, littoral combat ships (LCSs) could assist with this mission. A forward-based LCS squadron could maintain a sustained presence in lower-threat parts of the region, delivering on engagement commitments while freeing more capable combatants for essential duties inside the first island chain.

In wartime, the U.S. submarine force’s killing power coupled with long-range antiship missile strikes delivered from land- and sea-based aircraft would be the primary means to deny China control of the surface of the sea. Taiwanese antiship missiles and mines also would play an important role. Finally, while some key technologies would remain classified, the main thrust of these efforts would be publicly communicated, to influence Beijing’s decision-making in hopes of avoiding conflict.

Sea denial in the far term. The main tenets of developing and deploying sea-denial capabilities within the first island chain, and especially in the Taiwan Strait, would not change significantly over time. Instead, next-generation sensors and precision-strike weapons; a growing network of AI-enabled air, surface, and subsurface uncrewed assets; and expanded partner diplomacy would steadily strengthen sea-denial capabilities. Ships operating in high-risk waters would rely on cutting-edge electronic warfare systems and lasers for self-defense, augmenting kinetic weapons. Naval aviation, meanwhile, would adopt a more UAV-centric force structure, possibly built around a mix of large and smaller carriers, to provide a greater degree of operational resiliency.

The Marine Corps would continue to refine its expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) concept, providing a fluid, unpredictable, and lethal addition to the battlespace, increasing China’s uncertainty and thereby strengthening deterrence. Critically, Taiwan would accelerate investment in its porcupine defenses, making it a hard target to conquer and digest. Finally, constructive diplomacy with China would be sustained in hopes of avoiding conflict.

Sea control in the near term. Outside the first island chain, U.S. sea control will be less contested. With more space to maneuver, Navy carrier strike groups can spread out and pose a greater targeting problem for China. In such open waters, it would be the allies who need to command the surface of the sea to ensure the flow of vital trade to partner nations. Achieving sea control demands a fuller array of operational capabilities than those required for sea denial, including undersea sensing and tracking, while providing air defenses against ballistic, cruise, and hypersonic missiles. Those challenges, in turn, require resilient sensor and command-and-control (C2) networks that are largely self-healing and complemented with rapid-reseed architectures to assure communication. Given the complexity and simultaneity of these warfighting tasks, crewed ships will remain the heart of the open ocean sea-control effort for the years ahead, although increasingly augmented by unmanned assets.

Should conflict erupt, fleet-on-fleet combat almost certainly would occur at the operational level of war, setting the stage for an expanded struggle. In strategic terms, however, the trans-Pacific sea-control challenge would more closely resemble World War II’s Battle of the Atlantic than the U.S. Navy’s power projection drive across the Pacific toward Imperial Japan. In the Atlantic war, the United States endeavored to supply and sustain allied nations across the sea, striving to do so at an acceptable cost in terms of ships, men, and matériel. Given a similar open-ocean mission in the future, the Navy’s Pacific Fleet is suboptimally structured, with too many large ships dedicated to power projection and too few open-ocean escorts, submarines, and carrier-based antisubmarine warfare (ASW) assets. Furthermore, the U.S. Merchant Marine fleet today is but a sad shadow of its once-global presence.

The Navy’s new Constellation-class frigates will help address fleet shortfalls. Nevertheless, U.S. naval limitations highlight where allies and partners should focus their naval expenditures—on capabilities that complement U.S. efforts, forming a more effective and holistic deterrence effort. Such mission-sharing fleet design is not without precedent. During the Cold War, European NATO fleets largely focused on ASW, mine clearance, and littoral operations, leaving the carrier-based strike mission to the United States. To regain such synergies, allied operational planning should expand to include force structure and mission-sharing discussions. Given the rate of China’s naval construction, coordinated partner mission sharing should become a priority effort.

Sea control in the far term. Ensuring sea control in the deep Pacific and beyond after 2035 will remain a north star for naval planning. The mission would not change, but the ways and means to accomplish it would. Aircraft carriers would shift toward more unmanned and AI-enabled sensing, communication, refueling, and strike missions. Smaller, more numerous uncrewed surface and undersea vehicles would flesh out an increasingly resilient battle force network. Antisubmarine forces once again would become of primary importance in the deep water, placing greater emphasis on long-dwell tail ships, many of which could be unmanned. The antisubmarine warfare carrier concept may even see a revival, although this time hosting an array of manned and unmanned rotary and longer-range airpower assets. Cyber-secured networks would proliferate, offering C2 redundancy, even under attack.

Possibly, the Navy would reshape itself over time, moving away from a few large, expensive power-projection platforms toward the type of distributed maritime operations fleet that triumphed in the Battle of the Atlantic, thereby enhancing the security of distant U.S. partners. Directed-energy weapons would flow to the fleet, enhancing the defensive capabilities of combatants, and long-range sea strike missiles would again populate surface ships. Meanwhile, the Marine Corps would continue to mature and expand its littoral combat vision. All those efforts would be strengthened by growing multinational mission and force-design planning that would best take advantage of the combined economic, industrial, and shipbuilding strengths of Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the United States, among others.

Finally, all those efforts would be embedded within a global strategic deterrence framework aimed at preventing aggression elsewhere in the world should conflict erupt in Asia. U.S. strategic planning would rest on acknowledging that, in the face of multidomain threats, a major conflict in Asia would not be confined to that region. The struggle would be transregional, requiring U.S. naval power in the Indian Ocean, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean Sea, and even in the High North.

For the Navy, generating and sustaining sufficient presence and power to deter Chinese aggression would be the baseline requirement used to determine the size and composition of the future fleet. Working outward from the pacing threat of China, methodical and rigorous analysis would prescribe concurrent global operational requirements as part of a multinational, strategic assessment of U.S. naval power.

Raise the Bar, Near and Far

Keeping peace in the Pacific benefits all nations, including China. Adopting this four-campaign construct could help clarify and communicate to the American people—and their partners—how best to promote that objective.

Achieving sea denial near China and sea control in the deep water is not impossible. They are technically achievable, and this four-campaign construct to align programmatic investments, operational planning, and strategic communications could help meet both goals. Indeed, current naval planning and acquisition programs, in many cases, are moving in the right direction.

The United States has the technology, industrial power, and foreign partners needed to protect the peace. The question is whether it will move fast enough to raise the bar of deterrence before it is too late.

1. The White House, National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: October 2022); and U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States (Washington, DC: 27 October 2022).

2. Jude Blanchette and Ryan Hass, “The Taiwan Long Game: Why the Best Solution Is No Solution,” Foreign Affairs 102, no. 1 (January/February 2023): 103.