While Australia and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) have committed to providing the security of technology transfer through the AUKUS agreements, the RAN has not always delivered on its obligations in this area. The RAN needs to enhance its protective capabilities to ensure the most sensitive nuclear-propulsion technologies can be shared with Australia.

The Threat

The United States has shared nuclear propulsion technology with only one partner in 65 years and is understandably concerned about security.1 In the initial AUKUS treaty agreement, more than half the content was devoted to protective security measures.

The threat to nuclear capabilities is well documented. In 1988, Naval Base Clyde in Scotland was penetrated by four protesters during an antinuclear campaign. Three protesters managed to board the ballistic-missile submarine HMS Repulse and enter the control room. This incursion was possible without any forward planning or specialized equipment. If the intruders had been other than unarmed protesters, they arguably could have had access to an SSBN’s associated armaments.2

And there is the threat from inside. For example, in 2012, a leading seaman stole 12 9-mm pistols and two shotguns from HMAS Bathurst, a patrol boat on which he previously had served. He had authority to be on the base, and one duty member wrongly thought the robbery “may be part of an exercise.”3 More recently, Australia’s Director General of Security noted that espionage has overtaken terrorism as the principal security threat.4 Given that much of Australia’s science, technology, engineering, and mathematics workforce is foreign born, this could open opportunities for inside access by foreign agents.

If an AUKUS technology transfer were compromised, critical U.S. and U.K. technological advantages would be eroded.5

When the Time Comes to Cash the Check

Analysts predict AUKUS will shine a light on barriers to collaboration, including protective security measures.6 With a single misstep, support for AUKUS would likely evaporate.7 The RAN cannot stumble its way into securing the transfer of one of the most sensitive military technologies.

While the U.S. Navy’s master-at-arms (MA) and security limited duty officer (LDO) community has been reinvigorated to meet operational challenges, the RAN has not kept pace.8 A recent think-tank report on implementing nuclear submarines devotes just two lines to protective security.9 Similarly, an interview with Vice Admiral Jonathan Mead, head of the RAN’s SSN task force, detailed nine components to delivering AUKUS, with the fewest column inches devoted to security.10

It has been suggested the United States might base nuclear submarines in Australia to speed the AUKUS transfer, but this overlooks the fact that while billions of dollars have been invested in basing upgrades, not much has been done to harden or protect the facilities.11 This lack of protective investment is probably because RAN facilities have not faced direct threats for decades.12

Anthony Albanese at the AUKUS trilateral meeting on 13 March 2023, when the partners announced a pathway to produce a nuclear-powered submarine capability in Australia. Credit: Department of Defense (Chad J. McNeeley)

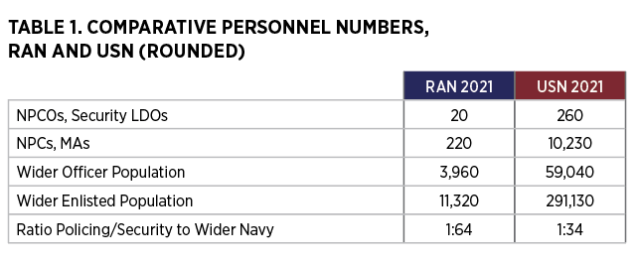

Any growth in the RAN’s naval police coxswain (NPC) or naval police coxswain officer (NPCO) communities—which are responsible for law enforcement and protective security tasks—is unlikely. While the Australian Defence Force is anticipated to grow by 18,500 individuals over the next decades, only 6,000 of those people have not been factored into existing capability acquisition projects.13 To maintain current staffing levels for the RAN’s policing and security capability, 1.6 percent, or about 100 of those 6,000 individuals, would need to be allocated to the NPCO and NPC communities, which in 2021 numbered just 240 people. To create a capability like the U.S. Navy’s security LDO and MA communities, the allocation would need to grow to a highly unlikely 10 percent.

The threat to Australia’s nuclear infrastructure is beyond the capability of Australia’s security industry to protect against it.

Before AUKUS, the RAN’s senior military police officer, the Provost Marshal–Navy, had responsibility for the security of visiting nuclear warships. Using military police assets recognized the value of police training, equipment, and capability in delivering protective security, but the relationship between security and policing is not necessarily understood by the warfare officers making decisions about securing AUKUS capabilities.

Defense analysts often comment on the RAN’s resistance to external ideas, but other elements of the Australian defense industry have the expertise to help develop and implement a plan for building the RAN’s security capabilities to support AUKUS.14 Refocusing NPCOs and NPCs on their core force protection and counterintelligence roles rather than ancillary tasks also would improve the RAN’s capabilities and likely reduce the need for personnel increases.

Ultimately, “the United States will still make tough judgments, as it should, about Australia’s capacity to step-up as a nuclear partner,” noted strategy consultant Peter Jennings.15 But without significant change, the RAN could be found wanting.

1. Mallory Shelbourne and Sam LaGrone, “Australia to Pursue Nuclear Attack Subs in New Agreement with U.S., U.K.,” USNI News, 15 September 2021.

2. Geoffrey Chapman et al., Security Culture: An Educational Handbook of Nuclear & Non-Nuclear Case Studies (London: Centre for Security Studies, August 2017), 21–24.

3. The Queen v. Evans, Matthew Robert Peter, Court of Criminal Appeal of the Northern Territory, 21248730, 16 August 2013.

4. Director-General’s “Annual Threat Assessment,” 9 February 2022.

5. Chapman et al., Security Culture.

6. Jennifer D. P. Moroney and Alan Tidwell, “Making AUKUS Work,” The RAND blog, 22 March 2022.

7. Marcus Hellyer, “Making the Most of AUKUS,” The Strategist, 27 October 2022.

8. Darryl Orrell, “9/11: A Turning Point for the U.S. Navy Master-at-Arms,” Navy.mil, 16 September 2021.

9. Andrew Nicholls, Jackson Dowie, and Marcus Hellyer, Implementing Australia’s Nuclear Submarine Program (Barton, Australia: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, December 2021).

10. Brendan Nicholson, “Australia’s Navy Is Cultivating ‘a Nuclear Mindset,’ Says SSN Taskforce Chief,” The Strategist, 27 October 2022.

11. Marcus Hellyer, “Australia’s ‘Damn the Torpedoes’ Path to Nuclear-powered Submarines,” The Strategist, 4 October 2022.

12. Michael Shoebridge, “Marles’s Defence Strategic Review—an Exploding Suitcase of Challenges to Resolve by March 2023,” Strategic Insights, 7.

13. Andrew Greene, “Defence to Grow to Largest Size since Vietnam War, Increasing by Nearly 20,000 People by 2040,” ABC.net.au, 9 March 2022; and Marcus Hellyer, “Where Will Defence Find 18,500 More People?” The Strategist, 17 March 2022.

14. Mick Ryan, “The Task Ahead for Rapid Capability Enhancement in Australian Defense,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 4 August 2022.

15. Peter Jennings, “Delivering AUKUS Success in Challenging Times,” Security & Defence Plus.