For several decades the Taiwan Strait has frequently been front-page news as China asserts its claims that Taiwan is part of mainland China, while the Taiwan government’s intention is to maintain its de facto independence.

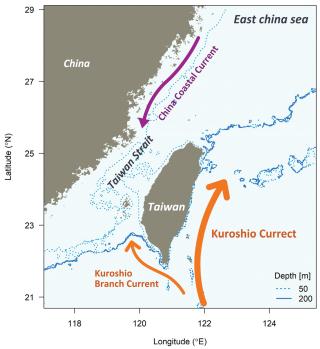

The Taiwan Strait is part of the South China Sea. It is 110 miles long and 81 miles wide at its narrowest point. The average water depth is 200 feet, and the major current flow is generally from north to south on the western side and south to north on the eastern side.

The strait’s seafloor is mostly continental shelf extending out from the Asian continent, with Taiwan on the outer edge. Taiwan’s 16 rivers discharge 150 million tons of nutrient-laden material annually onto the strait’s seafloor. China’s Yangtze River adds additional sediments. Over time, the rivers have created a 150-foot-thick layer of seafloor sediment at the southern end of the strait.

The strait is a major global shipping corridor, with 44 percent of the world’s container fleet moving through it in 2022. Freedom of navigation for all ships is guaranteed by the United Nations Law of the Sea Treaty.

While China is a treaty signatory, it illegally claims the strait is its inland waters. The global community maintains it is an international waterway. Maintaining innocent passage is why the United States and other nation’s naval vessels regularly sail through the strait.

Despite continuing threats from China to take Taiwan by force, there are tremendous commercial ties between the two. Taiwan is China’s fourth-largest trading partner; the value of all cross-strait trade was $319 billion in 2022.

Taiwan has 68 percent of the global market share in semiconductors, and their export to mainland China is critically important for the manufacturing base there. Regular airline service between the two helps facilitate this and other business relationships.

Taiwan has two primary resource activities in the strait: offshore energy and fisheries.

The large sedimentary deposits in the south end of the strait suggested the possibility of offshore petroleum resources. In early 2002, there was a brief agreement between Taiwan and China to undertake a $45-million exploration project for offshore oil and gas deposits. Almost nothing was found.

Taiwan now imports about 88 percent of its required oil and gas. With the potential for a Chinese maritime blockade, the government maintains a 30-day strategic national reserve of petroleum.

One offshore energy resource developing quickly is wind power. Currently, there are a few offshore installations in operation, but it is the Changhua Wind Farm development will make a major contribution to Taiwan’s energy grid. Wind turbines are being installed at four sites 20–40 miles off the central west coast of Taiwan in water depths ranging from 110 to 140 feet. Estimated project completion is 2030, and the generation capacity will be 2.4 gigawatts—enough power for 2.8 million homes.

The outflow of nutrients from rivers and mixing of surface currents create a rich biological environment for fisheries. Globally, Taiwan is one of the world’s major fishing nations; however, its coastal fisheries are under severe stress. Taiwanese fishermen’s catch has been in steady decline since the 1980s. Ten of the 16 major fisheries stocks having collapsed, four are overfished, and only one is considered healthy. Illegal fishing by China adds significant pressure on the resource.

Until military force is employed, China will continue to harass and pressure the island. China’s military forces do this by making threatening moves at sea and in the airspace between the two countries.

Much of this takes on a surreal quality as China and Taiwan continue to interact economically and financially. It is an environment of self-interest, as each nation benefits commercially from the arrangements.

Hopefully, trade and commerce will trump saber rattling over time. Military actions would gravely damage the economies of both China and Taiwan, as well as badly affect the world trade system.