White Sun War: The Campaign for Taiwan

Mick Ryan. Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2023. 340 pp. $22.95.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Commander Blake Herzinger, U.S. Navy Reserve

Whether in the sphere of political rhetoric or military acquisitions and strategies, Taiwan dominates conversations across not just the Indo-Pacific, but Europe as well. But these conversations are clouded by ambiguity, given the difficulty of forecasting or planning for a conflict that would be waged with weapons only recently developed by states of incredible military and economic power. Even the physical domain is undergoing changes not seen in centuries, with warming temperatures, rising sea levels, and increasingly severe weather patterns—all of which will factor into a conflict. Australian Army retired Major General Mick Ryan’s White Sun War takes on the challenge not only of presenting a comprehensive possible future, but also of using accessible and engaging fiction to bring his work to a broader audience.

Fictional intelligence, or “FicInt” as coined by August Cole, offers warfighters, decision-makers, and voters an informed look at what the future may hold, based on the author’s expertise in the principles of strategy and operations, as well as a comprehensive view of the evolving technological aspect of warfare. Ryan’s book shines here, guiding readers through the eyes of his characters to examine the effects of climate change on the Indo-Pacific and the strategic effects of cyber operations and space-based platforms, as well as the time-worn realities of war on the ground.

Ryan paints a military landscape defined by technological advances and professional military education, as well as organizational behaviors that enhance a defense force’s ability to adapt and overcome. The ability of U.S. military institutions to ingrain in their personnel the desire to remain creative, critical, and flexible in the face of the rapidly changing military environment will improve not just their warfighting prowess, but also their ability to avoid war.

Proceedings’ seapower advocates might bristle at a refrain that appears more than once in the text: “Wars are won on land.” The majority of the perspectives in White Sun War are indeed from characters in various ground, air, and space forces. But an attack on an island nation relies primarily on the ability to put sufficient forces ashore and sustain them over time. Seapower is the key. To wit, China has built a world-class navy in one generation and developed key capabilities required to hold at risk any maritime force that might attempt to intervene in a potential invasion. This slogan—wars are won on land because that’s where the people are—overlooks important conversations regarding ends, ways, and means. An attempted seizure of Taiwan would include fighting on land, but even Ryan’s narrative highlights that the loss of China’s maritime maneuver and logistics would likely be Taiwan’s best chance of concluding a war on favorable terms.

The importance of maritime logistics also is reflected in Taiwan’s former defense strategy, the Overall Defense Concept (ODC), which Ryan aptly references in the text. Through a thicket of sea mines, unmanned aerial systems, and antiship cruise missiles, Taiwan’s ODC sought to avoid major ground combat by eliminating the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s capability to sustain a war in the first place. So, while control of territory and population might be the ultimate objective in a war over Taiwan, it is indeed a war that can and will be won through the ability of either side to control or deny use of the sea. Any successful lodgments could then be mopped up by ground forces to eliminate any remaining threat, because they would be effectively cut off from sustainment or reinforcement. The logic therein being that Taiwan’s lack of strategic depth and disparity in size and capability makes it disadvantageous to rely on ground defenses.

But this is a novel by a career Army officer, not a seapower textbook. Ryan’s book offers the reader not only valuable perspective and tools for conceptualizing hypothetical scenarios, but also the view from someone with deep experience in land warfare with time spent at the highest levels of command. And the one thing sure to be true of a war for Taiwan’s future is that it would require joint synthesis of backgrounds, views, and capabilities. A careful reader should come away from White Sun War with improved understanding of each.

Ryan’s novel should be used as a teaching tool for U.S. forces as well as for a general public that wants to better understand the strategic environment in the western Pacific and how technology, climate, and geopolitics can affect all of us. His willingness to practice as he preaches, espousing the professional virtues of critical thinking and creative writing to enhance operational acumen and strategic awareness, should be a guiding light for leaders across all services, but particularly for junior officers exploring the vast space of military education. Learning is a journey that should not stop at any point in one’s career and, while it can be hard work, it can also be entertaining and engaging, as White Sun War so deftly proves.

Lieutenant Commander Herzinger is a research fellow at the United States Studies Centre in Sydney. He is a foreign area officer in the Navy Reserve and the coauthor of Carrier Killer, focused on the PLAN’s antiship ballistic missile program. He has been a Life Member of the Naval Institute since 2018.

Reading the Glass: A Captain’s View of Weather, Water, and Life at Sea

Elliot Rappaport. New York: Dutton, 2023. 336 pp. $30.

Reviewed by Joseph Reynolds

As a professor at Maine Maritime Academy, Elliot Rappaport prepares cadets for careers as professional mariners. His other job is captain of training vessels with the Sea Education Association at Woods Hole, where he is in charge of the sea science vessel (SSV) Robert C. Seamans, a 134-foot steel brigantine. The Association’s large sailing vessels give a small number of young people a chance to “learn the ropes” and become part of a team at sea, though the primary mission of the Seamans is as a scientific platform.

During Rappaport’s career he has visited exotic locales such as Greenland; Cadiz, Mexico; the Marquesas; New Zealand; and numerous tiny atolls in the South Pacific. His writing of place is evocative, and it has a gentle meandering quality, much like a sailing ship slowly but steadily moving with the trade winds across the Pacific.

Though there is a lot of sailing here, there also is science and history. A seasoned mariner, Rappaport has a vast knowledge of weather, currents, and oceanography. He has a keen and curious mind, qualities that make the best sailors. But he wears this knowledge lightly, not wearying the lay reader with names of lines or sails. Well, not too many, anyway.

This is not just a trip on a boat. Rappaport cleverly blends his lessons on the weather with cited marine accidents, and he puts on his sailor’s cap to take a hard look at the close calls and unfortunate losses of vessels at sea. Regarding the loss of the El Faro with 33 on board during Hurricane Joaquin in 2015, it is interesting to note Rappaport’s sympathies regarding the burdens of captaincy. He knows it because he has lived it.

He does not exonerate Captain Michael Davidson of the El Faro, but the book does address Rappaport’s own difficulties making choices. To leave port or stay? Speed up or slow down? These are the captain’s decisions in the end. And Rappaport is honest about times he and his vessel might have had different outcomes. As they say, a ship is meant to go to sea. There are always risks involved. There is a dash of Melville and Conrad in these dark musings, but for the reader safe at home, that’s not a bad thing.

The book is not just a catalog of maritime disasters, though. There are charming and comical moments, along with little things we take for granted on land that are different at sea. Rappaport is not afraid to poke fun at himself, even mentioning the occasional mild bout of seasickness. When he gets off the ship to go home, a fellow captain says to him, “One day you’re the man, the next you’re just a guy.” Too true!

This is a lovely book for armchair sailors, and Rappaport is a fine writer. I will warn readers that some of the passages on the weather can be dense, but Rappaport evokes the timeless nature of life at sea, voyages not too unlike the ones ancient Polynesian navigators made. Reading the Glass is a fine book, and a trip worth taking.

Mr. Reynolds graduated from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in 1987 and is a chief engineer in the U.S. Merchant Marine, though right now he is “just a guy.” He lives in South Carolina.

In the Blood: How Two Outsiders Solved a Centuries-Old Medical Mystery and Took on the U.S. Army

Charles Barber. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2023. 281 pp. $29.

Reviewed by Robert M. Cassidy

In the Blood tells the story of the invention and adoption of a device that represents the biggest advance in hemostatic method in centuries. Quik-Clot Combat Gauze was a paradigm change in stopping bleeding. The Marine Corps and the Navy tested it—and adopted it with unprecedented celerity. It saved Marine lives during the first months of the Iraq War. The U.S. Army rejected it, refuted it, and resisted adopting it from 2003 to 2008—five years of two wars that saw many traumatic bleeding wounds. QuikClot Combat Gauze is now used by first responders, hospitals, and emergency rooms around the world. It is available for purchase at Walmart. The most interesting thing about this story, however, is the background of the two people who made this lifesaving idea happen.

In the Blood is a David versus Goliath tale. The two inventors fought for years against the Army’s powerful bureaucracy to get QuikClot recognized and approved for use across the services. The Marine Corps and Navy exhibited pragmatism and nimbleness in embracing this inexpensive and effective bandage. The Army, however, squandered millions of taxpayer dollars pursuing four other, less effective solutions ultimately abandoned for QuikClot.

On the David side, this story is about a genius engineer with loads of curiosity and a former national championship crew coach with a literary bent and lots of marketing brio, who team up to effect a sea change in hemostatic method. On the Goliath side, this is a tale about a brilliant but arrogant Army colonel surgeon in sole command and control of a hierarchical bureaucracy—the Institute for Surgical Research. The colonel had served in Somalia and operated on many badly bleeding soldiers. As a result, he made the search for new stop-the-bleeding agents his life’s purpose. Both sides in this incredible story had the same goal, to find a better way to stop the bleeding and save lives.

In fall 1983, Frank Hursey had the idea that mineral zeolite might be used like a sponge to soak up the water in blood and thus separate the water from the platelets that cause blood to clot. He was the first person to conceive of clotting blood by removing the water it contains. Other scientists and doctors looking for better ways to stop bleeding had only looked to add something to the blood, like clotting proteins.

Hursey’s genius was that he looked in the opposite direction from every doctor and scientist. He did not meet with success until 1999, when he met and partnered with Bart Gullong, an ideas guy with a background in literature and plenty of stamina. They struggled for years against the Army to get QuikClot widely in use. They prevailed. QuikClot Combat gauze costs $9.80 per package. The least expensive product the Army endorsed cost $98 per package, and it was not effective. Another Army choice had cost $17,000 for the required doses, and it killed soldiers by causing blood clots in the brain and heart.

There is much more to this story, but there is no need to spoil it. The storytelling is masterful. In the Blood is a study of both remarkable success and utter failure with innovation. It should be on the service chiefs’ reading lists.

Dr. Cassidy is a retired U.S. Army colonel who teaches at Wesleyan University. He has served in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere in the Middle East.

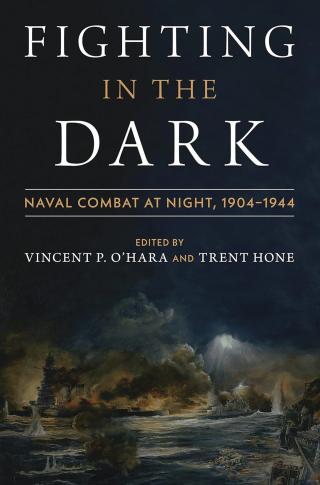

Fighting in the Dark: Naval Combat at Night, 1904–1944

Vincent P. O’Hara and Trent Hone, eds. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2023. 348 pp. $40.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Kyle Cregge, U.S. Navy

Parents of young children often become amateur scientists or on-demand researchers, as our kids’ questions about why and how remain unhindered by our petty problems of today. “How does a honeybee see, Dad?” Whether drawn from a TV nature show or a dutiful internet search, one finds that while our buzzing friends are bound by the inability to see infrared light, they can see far more ultraviolet light than human eyes have evolved to see.

Fighting in the Dark: Naval Combat at Night, 1904–1944 is a story of 20th-century navies evolving their vision through emerging technologies and at-sea experience. Naval historians Vincent P. O’Hara and Trent Hone have collected seven historical essays on the development of naval night combat over four decades, from the 1904–5 Russo-Japanese War through the end of World War II.

Each story focuses on a different nation and its naval adaptation to night combat, in chronological order. Every chapter is in part a vignette on a surface-to-surface night battle, wrapped in the history of the technical and tactical developments and assumptions that led to that navy’s night in question. The contributing authors are each successful in their own way. Particularly special

is the contribution of late Royal Australian Navy Rear Admiral James Goldrick—himself an esteemed historian and naval officer—whose essay on British night fighting from 1916 to 1939 represents his last publication across a deep and successful academic and professional career.

It is too little to say Fighting in the Dark should be required reading for naval officers both afloat and in the halls of leadership. Its pages should be dog-eared and its analogies to today discussed relentlessly. These men across countries and time encountered the same problem we have today—only now we have chosen different emerging technologies and different portions of the electromagnetic spectrum across which to see, listen, think, and fight.

Was the searchlight a critical defense against inbound torpedo boats that could deny their attacks? Despite early theories recounted in this book, our predecessors learned that rather than a defense to be maintained persistently, the searchlight more often served in the counterdetection and illumination of oneself, stimulating adversary attacks—it was best used only at the last moment. Similarly, early U.S. torpedo tactics development and radio employment technologies that were taken up as early as 1915 to enable distributed striking power from “torpedo destroyers,” went into disuse during the interwar period. These skills had to be relearned during the maelstrom above Guadalcanal’s Iron Bottom Sound. More than a century after 1915, we again find the relearning of “distributed lethality” from destroyers and the desire to reinstitute tactics at the center of our profession in the pages of Proceedings.

Fighting in the Dark’s conclusion includes the 1943 story of then-Captain Arleigh Burke mentoring a junior officer on “the difference between a good officer and a poor one.” After the junior’s detailed response, Burke offers, “The difference between a good officer and a poor one is about ten seconds.” That time is the central factor in combat, most especially at night, remains as true today, if not more so. As the late Captain Wayne Hughes repeated, attacking effectively first is among the best indicators of success in naval combat. If in Burke’s time, the speed of weapons was measured in tens of knots and an officer’s judgment in ten seconds, how will we be judged tomorrow? How many seconds will we have? Five? One?

There is nothing new under the sun—and nothing new without it. Only new darkness and old lessons. Go see what you have been blind to. Go read Fighting in the Dark.

Lieutenant Cregge is a surface warfare officer. He is the operations officer for the USS Pinckney (DDG-91).