In the long peace since the end of World War II, the Indo-Pacific has experienced remarkable prosperity, underpinned by the security of stable alliances and the good order of U.S.-led global governance. The Indo-Pacific now stands as a strategic and economic center of gravity, comprising eight of the ten most populous nations on earth, seven of the ten largest militaries, and 12 members of the G20, all connected to each other and the rest of the world through some of the busiest international sea lanes.1 However, today’s rules-based global order is under threat by China and a resurgent Russia, both of which are opposed to the U.S.-led system and believe “the liberal international order poses an existential threat to their regimes.”2

In particular, China—backed by a significant military buildup and aggressive legal and diplomatic stances—aims to challenge essential elements of the international rules-based system and rewrite the rules that govern the maritime zones in the South China Sea. These changes have broad implications for the security and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific.

Maritime Trade Drives Prosperity

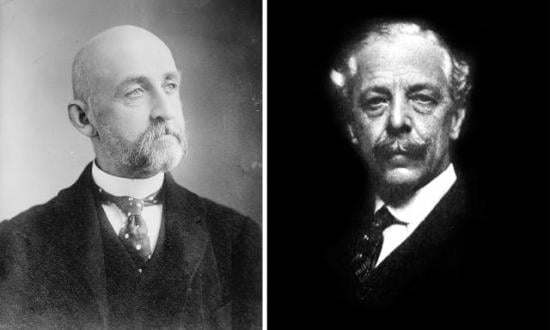

Writing just prior to the turn of the 20th century, Alfred Thayer Mahan argued that the key to sustaining national power is continued economic growth, and this economic growth is, in turn, driven by unhindered access to international trade. He realized that, following industrialization, nations depend on international trade, and if isolated, their economies eventually will collapse, leading to domestic upheaval that could threaten their survival.3

Applied in a modern context, consider that two-thirds of Australia’s two-way trade is with the Indo-Pacific.4 The sudden loss of exports would damage the economy through loss of jobs and revenue, and the loss of imports would cripple Australian society, as “almost every aspect of the Australian economy is dependent on petroleum imports.”5 Should Australian sea lines of communication be compromised, the consequent shortage of diesel, essential for farming and food distribution, would quickly cause food insecurity. What’s more, in a crisis, the country’s military options would be severely constricted as aviation gasoline and marine diesel supplies dry up.6 Under these circumstances, Mahan’s predictions of social unrest could be realized.

Maritime Trade Depends on UNCLOS, Security

The U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is a crucial expression of the rules-based order. It outlines shared maritime rights, carefully articulating different maritime zones, their associated levels of sovereignty, and the accompanying freedom of navigation on which seaborne trade depends. The convention embodies the idea that the high seas is a global common, where international trade can travel unimpeded.

China’s actions in the South China Sea, its expansive maritime territorial claims and disregard for UNCLOS, threaten the movement of maritime trade and therefore the vital interests of all Indo-Pacific nations. Only through the protection of maritime rights by like-minded navies can the good order and security of the maritime domain—and thus the prosperity of the Indo-Pacific—be upheld.

Mahan believed a navy’s enduring purpose is to ensure continued access to the maritime commons and protect seaborne international trade.7 Today, however, advances in persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), long-range precision strike, and undersea warfare capabilities call into question the joint force’s ability to maneuver or to guarantee maritime trade during times of crisis and conflict.

Sea Control or Sea Denial

Australian strategist Hugh White argues that advances in technology have made warships vulnerable and, as a result, have made achieving sea control difficult. Consequently, he concludes that navies no longer can defend maritime trade in a conflict. Therefore, White argues, Australia should restructure its forces around sea denial capabilities to deter an adversary by placing its maritime trade at risk and to defeat an adversary’s maritime forces as they approach the mainland.8

On the other side of the debate, Rear Admiral James Goldrick pointed out that maritime trade is vital to the nation, especially during a conflict in which energy security underpins military response options and national food security. Consequently, he argued that there is no choice but to defend maritime trade despite the imbalance between sea control and sea denial strategies. In doing so, Goldrick emphasized that sea control is required in a location only for the time it takes to achieve the movement needed, and that essential maritime traffic can be rerouted outside missile ranges and likely lines of submerged approach. He also pointed out that effects at sea no longer are provided by a single service, but by the joint force across all domains, which when combined, can achieve enhanced protection effects. He concluded that because of all these factors, sufficient sea control is still achievable in a modern conflict within the current force design construct.9

Given the extremely long acquisition lead times associated with naval procurement, force structure decisions must be made with an eye to likely future developments, the pace of change, and the risks associated with getting it wrong. White’s conclusion assumes that the asymmetry between sea control and sea denial strategies will last; however, the pace of technological change is furious and is swiftly recontouring the character of war. Emerging technologies such as speed-of-light weapons to complement existing kinetic defenses and torpedo hard-kill systems may shift the balance back toward a sea control strategy. Should this occur, the assumptions underpinning White’s proposed sea denial strategy and the associated force structure will be superseded, changing the calculus of force design.

In contrast, Goldrick’s argument assumes there will be sufficient joint assets available to achieve the required sea control effects, to protect the volume of trade needed, for the duration necessary, to sustain the nation in conflict. His argument that maritime shipping can be rerouted assumes that nonsovereign merchant shipping would be willing to assist during conflict and that there is part of the sea or a destination port outside the range of an adversary in an age of persistent ISR, long-range precision strike, undersea warfare, and hypersonic fractional orbital bombardment capabilities.

Both arguments present risks to force design decisions, and given procurement lead times, policy-makers have to make tough choices now to engineer a force structure that can meet or pivot to whatever future emerges. But the type of force that can be engineered depends on how much time there is to adapt and prepare.

University of Pennsylvania professor Michael Horowitz argues that it is impossible to maximize capabilities across all periods simultaneously. He contends that bets need to be made now on readiness and capability decisions for the likely timing of the next conflict. In particular, if war is imminent in the next two years, navies of the Indo-Pacific will be going to war with what forces they already have, and readiness should be emphasized because there is insufficient time to modernize old or procure new platforms. However, if war is predicted later in the 2020s, new warfighting tactics, modernization, and delayed retirement of platforms should be considered. If war is more likely in the 2030s, investments in emerging technologies and new operational and force design concepts can be factored into procurement decisions.10

Regardless of the timing of the next conflict, Mahan’s warning about the consequences of losing maritime trade in an interconnected Indo-Pacific is still relevant. Despite the gravity of the threat presented by China, sustaining trade through competition, crisis, and conflict must be a key strategic end for all like-minded nations of the Indo-Pacific. Only through the collective protection of UNCLOS can access to the maritime commons be ensured, and it will be through these collective efforts that the good order of the maritime domain, the security of maritime trade, and the prosperity and stability of the Indo-Pacific will be secured.

1. LGen Angus Campbell, AA, “Preparing for the Indo-Pacific Century: Challenges for the Australian Army,” Chief of Army Address to RUSI, 2017.

2. Thomas Wright, “Stresses and Strains on the Global Order,” in Ironclad: Forging a New Future for America’s Alliances, ed. Michael Green (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 15.

3. Nicholas A. Lambert, “What Is a Navy For?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 4 (April 2021).

4. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Trade and Investment at a Glance 2021."

5. Greg Colton, “Fuel Security: Why the RAN Should Prioritise the Indo-Pacific,” The Interpreter, 6 October 2017.

6 James Goldrick, “Australia’s Essential Need: Not Seaborne Trade But Seaborne Supply,” The Interpreter, 3 September 2021.

7. Lambert, “What Is a Navy For?”

8. Hugh White, “Australia’s Seaborne Trade: Essential But Undefendable,” The Interpreter, 27 August 2021.

9. Goldrick, “Australia’s Essential Need.”

10. Michael Horowitz, “War by Timeframe: Responding to China’s Pacing Challenge,” War on the Rocks, 19 November 2021.