In late 2021, U.S. Cyber Command’s Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF) deployed to Ukraine its largest hunt-forward operation (HFO) to date. Like a traditional reconnaissance element, these U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard defensive cyber operators and intelligence analysts hunted and gained insight into Russian malicious cyber activity as tanks massed along Ukraine’s border.1 They worked in-country, side by side with senior Ukrainian officials, for nearly 70 days to assist in the cyber defense of multiple critical networks.2

The hunt-forward team physically integrated with U.S. theater partners from U.S. European Command and U.S. Special Operations Command Europe for contingency purposes and transitioned the in-country mission to remote operations days before the Russian invasion—continuing to remotely support Ukraine in its cyber defenses.3 “This sort of mission is critical to both our nations’ defenses in cyberspace—particularly in the face of Russian aggression,” noted Army Major General William Hartman, commander, CNMF.4

This was the first HFO conducted during the lead-up to ground combat, and it demonstrates how the United States can use defensive cyber operations as part of a persistent engagement strategy before and during future conflicts. Ukraine has demonstrated the power of defense, resilience, and relationships during conflict—from both a general military standpoint and a cyber perspective.

Active Defense

In mid-January 2022, Ukraine experienced the first wave of cyberattacks attributed to Russia. Consisting primarily of website defacement and destructive malware campaigns, these attacks affected the Ukrainian government and local organizations but were all merely disruptive, with Ukraine recovering within days.5 Various forms of malware have continued to disrupt Ukrainian systems throughout the war, but none have been debilitating or caused massive, long-term outages. Ukraine’s defense of its critical systems and networks—both informational and operational—has improved since the 2014–15 Russian invasion and the cyberattacks that caused power blackouts across Kyiv and neighboring regions and the 2017 NotPetya cyberattack that caused widespread, cascading outages.

Although Ukraine’s ability to defend its government and critical infrastructure is not bulletproof, it demonstrates the value of active cyber defense against an adversary before and during conflict. The United States must continue to practice this “shields up” mentality, actively testing, improving, and defending critical systems against cyber threats.6 Marine Corps and joint cyber protection teams (CPTs) can assist in defense of service-level systems and networks, critical systems and infrastructure, and allied-partner networks in areas where U.S. forces will operate during potential future conflicts. While offensive cyber operations are an aspect of warfare, cyber defense of the homeland, military, and allied-partner systems is essential to national resilience, as seen in Ukraine’s defense against Russia.

Increased Resilience

Cyberattacks prior to and during conflict are no longer a question; however, their scale and scope will vary. In the next conflict, U.S. ground, air, and sea forces will see disruptive cyberattacks, at a minimum.

As of April 2022, Microsoft reported more than 200 Russia-attributed cyber-attacks launched against Ukraine during the war, including 40 discrete cyberattacks targeting hundreds of systems across multiple organizations.7 While most attacks were only disruptive, the number of attempts is significant, and they continue today. What is notable is Ukraine’s ability to rapidly recover from multiple, consecutive, disruptive cyberattacks.

As in kinetic fights—taking incoming fire and firing back—Ukraine’s ability to rapidly assess affected systems and coordinate with the hunt-forward team to better understand the attacks (initial compromise of systems, overall attack timeline, attribution, etc.) allowed Ukraine to reposition its own cyber forces and better defend against future attacks. Concurrently, the HFO CPTs were able to better understand the Russia-attributed cyberattacks and share and apply this insight in defense of potential attacks against systems throughout the West.

This resilience in response to an opponent’s cyber warfare is a skill the U.S. military will require during future battles. Without the ability to quickly respond to and recover from cyberattacks, the force—and the nation—will face longer outages that could affect military or civilian systems, contest command and control, and degrade public morale.

Improved Partnerships

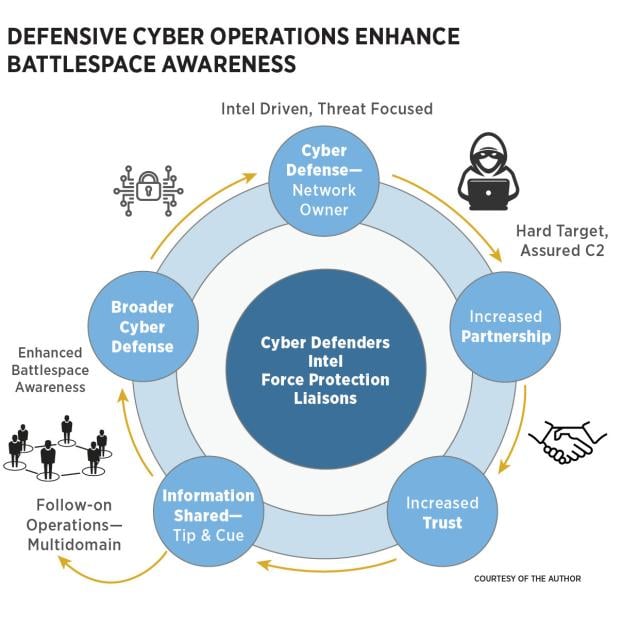

The HFO enhanced the strong, enduring partnership between the United States and Ukraine, particularly in the cyber domain. This relationship will remain critical during future conflicts, whether or not they involve Russia. When a national-level CPT is deployed to conduct an HFO in an allied country, the team physically integrates with the host nation for months, working alongside U.S. embassy personnel, other agencies, and various allied senior military and government officials. U.S. military officers and staff noncommissioned officers directly negotiate and coordinate with host-nation government and cybersecurity officials, and the relationships they build while assisting the country with cyber defense can evolve into professional partnerships across other military sectors—enhancing intelligence, information, and situational awareness across the battlefield.

From the HFO in Ukraine, relationships with mission partners developed significantly over the months. Continued cyber defense support from the CPT and the sharing of various indicators of system compromise with Ukrainian partners contributed to their sharing of information with the hunt-forward team, ultimately benefiting cyber defense across the West.

U.S. officials noted that “Ukraine has to date fared much better in the face of Russian cyber incidents than initially expected. [In part because of] the early engagement of U.S. Cyber Command teams to assist.”8 This collaboration also strengthened Department of Defense operations and contributed to imposing costs on Russia in the cyber domain. In future conflicts, the U.S. military must incorporate and leverage CPTs at the tactical and operational levels to achieve strategic-level initiatives, deter threats, and shape theater conditions across the area of responsibility—in support not only of cyber operations, but across multidomain operations.

Persistent Engagement

As the Cyber Mission Force matures over the next few years, so will its capabilities to support the services, U.S. Cyber Command, and the joint force. Cyber Command Commander General Paul Nakasone explained the synergy between defensive and offensive cyber operations and how this contributes to a persistent engagement strategy. “Through persistent presence, persistent innovation, and persistent engagement, we can impose costs, neutralize adversary efforts, and change their decision calculus,” he said. “In doing so we build resilience, defend forward, and contest adversary activities in cyberspace.”9 Persistent engagement, defined as “the need to constantly interact with adversaries in cyberspace,” emphasizes the “importance of speed and agility to achieve success.”10 Employment of CPTs prior to conflict for persistent cyber defense of U.S. and allied systems offers increased mission assurance and assured command and control.

In addition, expanding opportunities for collaboration provides layered defenses within cyberspace. For example, in coordination with joint and multinational exercises, a service-level CPT could hunt for malicious cyber activity on systems relied on by U.S. forces, while a national CPT concurrently hunts for malicious cyber activity on a host-nation network—both networks chosen based on intelligence and their support of U.S. forces and allies. When multiple defensive cyber missions are incorporated in one area of responsibility, adversary cyber tactics, techniques, and procedures can be shared among the services and with host-nation, Department of Defense, and interagency stakeholders. Increasing and prioritizing defensive cyber hunt missions across the force will better achieve a persistent engagement strategy against a range of adversaries within cyberspace.

The ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from cyberattacks is critical for defensive cyber operators. A level of incident response knowledge of friendly force systems will allow operators and teams to anticipate and be better prepared during nonkinetic conflict. Incorporating such training is critical as the defensive cyber warfare military occupational specialty is further developed. This will allow the United States to regain the initiative after cyberattacks. Based on lessons from Ukraine, Microsoft recommends organizations take action, including “to have and exercise an incident response plan to prevent any delays or decrease dwell time for destructive threat actors.”11

Lessons from Ukraine

The Russia-Ukraine war demonstrates how important cyber defense is in upholding trust and morale among the local population and deterring cyberattacks during a conflict. Cyberattacks will occur—both before and during a conflict—and nations must anticipate them and be prepared to quickly assess, recover, and respond. Key partnerships established early between the military and allies, industry and agencies, and CPTs conducting persistent defensive cyber operations forward are critical enablers.

Defensive cyber warfare is active. Since 2018, CNMF has grown the HFO mission and increased CPTs to achieve persistent engagement and impose costs on adversaries while strengthening partnerships. General Nakasone noted, “What we’ve learned over the nine different HFOs [in 2021] is the fact that consistent engagement with a series of partner nations is really valuable.”12 Understanding defensive cyber operations is essential to success in future conflicts. The U.S. military must continue to analyze the lessons of Ukraine now, and in the years to come, to support future force design.

1. Cyber National Mission Force Public Affairs, “Before the Invasion: Hunt Forward Operations in Ukraine,” CyberCom.mil, 28 November 2022.

2. U.S. Cyber Command, “Posture Statement of Gen. Paul M. Nakasone, Commander, U.S. Cyber Command, before the 117th Congress,” CyberCom.mil, 5 April 2022.

3. U.S. Cyber Command. “Posture Statement of Gen. Paul M. Nakasone.”

4. Cyber National Mission Force Public Affairs, “Before the Invasion: Hunt Forward Operations in Ukraine.”

5. Microsoft Digital Security Unit, “Special Report: Ukraine, An Overview of Russia’s Cyberattack Activity in Ukraine,” 27 April 2022.

6. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, “Shields Up!” www.cisa.gov/shields-up.

7. Microsoft, “Special Report: Ukraine.”

8. Mark Pomerleau, “Ukraine Crisis Shows Effectiveness of Cyber Command’s Persistent Engagement, Nakasone Says,” FedScoop.com, 6 April 2022.

9. C. Todd Lopez, “Persistent Engagement, Partnerships, Top Cybercom Priorities,” Defense.gov, 14 May 2019.

10. Suzanne Smalley, “Nakasone Says Cyber Command Did Nine ‘Hunt Forward’ Ops Last Year, Including in Ukraine,” CyberScoop.com, 4 May 2022.

11. Microsoft, “Special Report: Ukraine.”

12. Pomerleau, “Ukraine Crisis Shows Effectiveness of Cyber Command’s Persistent Engagement.”