Open-source intelligence (OSINT) is the process of using publicly available information and tools to create (usually public) intelligence. Fact-checkers and whistleblowers have employed OSINT, but recently its utility for military purposes has gained attention.

While OSINT has been a subject of official study since at least the 1940s, it has become more privatized in the 21st century. In 2016, for example, users on the notorious social media site 4Chan gave Russia the coordinates of a terrorist training camp. However, Russia’s conflict with Ukraine has resulted in a large-scale civilian effort to track Russian activities there and, in particular, to analyze the Russian invasion that began in early 2022. As the United States prepares for potential conflict with peer adversaries, it is important for military professionals and the public to learn about OSINT, the threats it could pose, and how the United States can use this community as an asset for future conflicts.

The Three Pillars of OSINT

OSINT is not just the information it produces or its capabilities. Three key “pillars” comprise it:

Data sources. OSINT researchers need data to analyze.

Information aggregation. OSINT researchers need references and places to store information obtained by investigation. They also need to be able to transfer this information to each other.

Communication. To employ “wisdom of the crowd”—the basis of OSINT—researchers need to be able to discuss and debate with one another.

Each pillar is critical. If any is compromised, OSINT cannot be conducted effectively.

OSINT in Ukraine

Before the invasion of Ukraine, researchers paying attention to tweets from Russian accounts showing Russian trains loaded with tanks and armored vehicles. By geolocating these photos and following the train tracks, OSINT researchers quickly identified the size and locations of a massive buildup occurring not just on the Russia-Ukraine border, but along parts of the Belarusian and Moldovan borders as well.

In the opening days of the invasion, Twitter exploded with records of the fighting. Videos emerged of tanks getting hit with rockets, armored vehicles fighting armored vehicles, and bodies in the streets. The OSINT community started to dig in. Researchers started identifying individual vehicles and tracking their status. Twitter users @GirkinGirkin and @no_itsmyturn identified more than 400 vehicles in the first ten days of the invasion alone. Others began documenting the invasion as a whole. For example, UAWarData created a map of Russian troop movements across the front, with updates about every three days, while a MapHub user created the Eyes on Russia project, creating a database of images organized by their content.

The Russian government’s reaction to the footage coming from Ukraine was to attempt to limit its own people’s exposure. Roskomnadzor, Russia’s media surveillance department, outright banned Facebook, and later in the year there were reports the agency had limited access to Twitter as well. This attempt at controlling the communication pillar was not very effective. Any citizen using a virtual private network (VPN) could evade the ban, and anonymous services such as Telegram resist limitation by such measures.

This action, however, also limited the distribution of pro-Russian sources, which created a pro-Ukrainian bias regarding what footage was available on social media. Combined with global public opinion, this led to an extremely one-sided OSINT community. UAWarData did not have data on Ukrainian forces or movements until 27 April, and the OSINT community at large did not keep track of Ukrainian vehicles or force capability beyond those captured from Russia.

The unified global OSINT effort aimed at a single objective poses a critical question: how can the United States replicate the success of Ukraine and its supporters to ensure the OSINT community advantages the United States in a future conflict?

China’s Media Control

Over the past two decades, the Chinese government has created an “information bubble” that keeps its citizens insulated from the West. Internet censorship allows it to control the sources, disable information aggregation, and control the communication of its citizens, giving China effective local control over all the OSINT pillars. This makes it incredibly resistant to OSINT efforts.

In China, most media is shared through WeChat, China’s state-sponsored, state-approved, and state-monitored media sharing site. Twitter, Facebook, and other Western social media services are blocked in China; as a result, communication between Chinese sources and the rest of the world is often limited.

China has another advantage: Its government controls the maps. In 1992, the Seventh National People's Congress passed a law limiting map-making to approved cartographers and decreed that all maps must use state-approved datums only. This means, for example, that Google Maps can map China using only the party’s guidelines. Comparing the approved maps with GPS data and other mapping software depicts China differently than satellite imagery. This makes geolocation in China difficult, with geographic coordinates not translating between mapping services.

Compared with Russia’s reactive measures against OSINT in Ukraine, China has taken a very proactive approach. With state-controlled domestic communication and restricted international communication, OSINT is very difficult inside China.

Naval OSINT

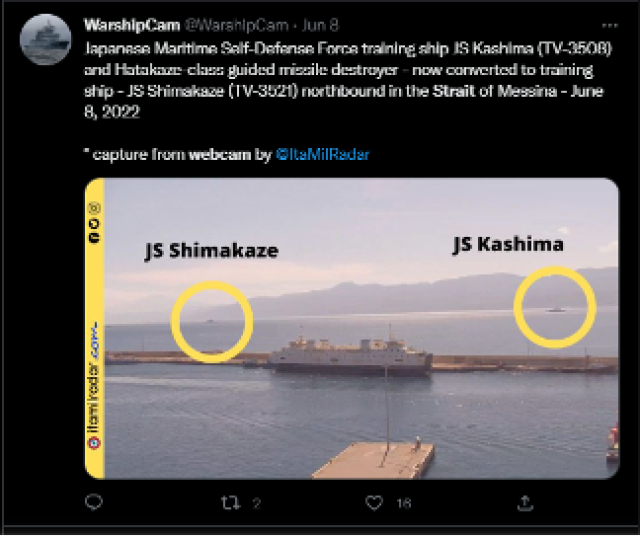

The field of Naval OSINT relies on two key sources: having eyes on key locations such as ports and straits and using publicly available information such as the automatic identification system (AIS) and satellites.

Smartphones are an indispensable asset for open-source intelligence. Straits and ports generally have large populations nearby, and therefore many smartphones that can take and post photos of warships in transit. Further, many are observed by live-streamed webcams, which anyone with the link can watch. Thus, warships transiting a strait halfway across the world can easily be spotted and shared from the comfort of a couch.

Credit: @WarshipCam [13]

Outside these key locations, it can be more difficult to track a ship's movement. AIS data again plays a role, and so do publicly available satellites.

Websites such as Maritime Traffic [14] and ShipXplorer [15] allow the general public to see the location of any ship broadcasting AIS data at any given moment. While warships do not tend to broadcast AIS, the few times they do, anyone can see where the warship was and in what direction it was heading at the time.

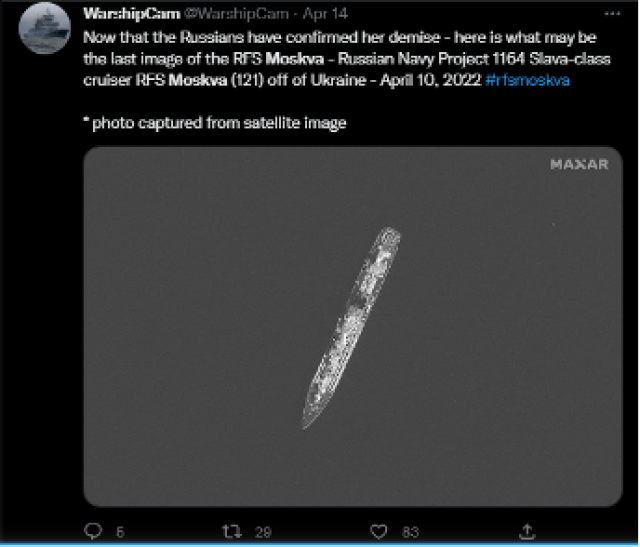

Publicly available satellite data, such as that from the Sentinel SAR satellite constellation, is also very helpful. Even so, trying to find a ship in the middle of the ocean is difficult. However, this could be automated using machine learning, as scholars have detailed.

Credit: @WarshipCam

When a photo is obtained, the OSINT community shares it for analysis. One common method is to post it to Twitter, leaving a tag that includes the ship’s name and the location at which it was spotted. This allows later data acquisition by searching for the right account and ship name. For example, the Twitter account @WarshipCam has photos of the USS Zumwalt (DDG-1000) in and out of San Diego and elsewhere throughout 2022.

Analysis requires photographs of ships over time. WarshipCam and ShipSpotting keep large databases of ship pictures, which can be cross-referenced with a new photo to identify almost any warship or system configurations on board. Some enterprising individuals have even used machine learning algorithms to automatically detect the presence of a warship using any port webcam.

Controlling OSINT

Many prospective adversaries control certain pillars of OSINT in their countries, leaving them less vulnerable to integral threats posed by OSINT.

Russia. Russia’s ability to limit internal communications, at least in part, is an obstacle to effective OSINT.

China. China’s strong internal controls over every OSINT pillar makes conducting OSINT very difficult inside the country itself. However, China has little control of these pillars externally, leaving it vulnerable to some OSINT gathered from outside.

The United States. By average monthly users, the top four social media sites are all owned by companies in the United States. This could lead to a belief that the United States can gain control over the communication pillar at a moment’s notice. However, if the United States attempted to suppress OSINT activities on these services, the community would be able to shift to others with relative ease.

Thus, it is difficult to argue that the United States has control over any of the OSINT pillars. This makes OSINT a unique threat to the United States relative to its adversaries.

OSINT as Threat

It cannot be assumed that the OSINT community will favor the United States in a future conflict, and the armed forces must anticipate that intelligence on its movements will be collected by the public, inadvertently or deliberately, and used by the enemy.

Hostile activities of the OSINT community threaten two aspects of warfare: the ability to hide actual force capacity and the ability to employ surprise.

Damaged ships and the state of their repairs will be scrutinized by the OSINT community. Publicly available information also will record the condition of U.S. warships, how many are still operable, how many should be presumed lost, and so on. Maps such as those of Russian forces in and around Ukraine might detail the positions of U.S. warships at any given time.

Further, a large-scale surface operation usually requires the preparation of forces at one or several ports. Any force abruptly put to sea would be identified, and the OSINT community would infer that a major operation is underway, spoiling the Navy’s ability to employ surprise.

OSINT as Opportunity

Given the threat posed by OSINT, the U.S. Navy must consider how to mitigate the likelihood of a hostile OSINT environment.

Source availability and public opinion have a significant impact on this, as the strong pro-Ukraine OSINT output demonstrates. Therefore, building and maintaining positive global public opinion will be crucial. If the United States appears to be the “good guys,” it can expect the OSINT community to self-regulate its analysis of “friendly” forces. Winning the hearts and minds of the global public is essential.

Another way of preventing a hostile OSINT environment is to increase the quantity of pro-U.S. Navy sources. If sailors, Marines, and other military personal can record the enemy and share their images, subject to security approval, this can have a positive effect on that. This would reduce the chance of the OSINT community prematurely sharing and analyzing sensitive information.

First Amendment rights increase the United States’ potential vulnerability to OSINT, but the community could also provide valuable information not otherwise easily obtainable. It is reasonable to expect our adversaries to limit freedom of speech, and in doing so push the OSINT community’s favor towards the United States. This opportunity should be embraced. Through encouraging and assisting the OSINT community, the United States can turn this potential threat into an advantage against its adversaries.

Editor’s Note: The author obtained permission from Twitter users to use the screenshots of their tweets.