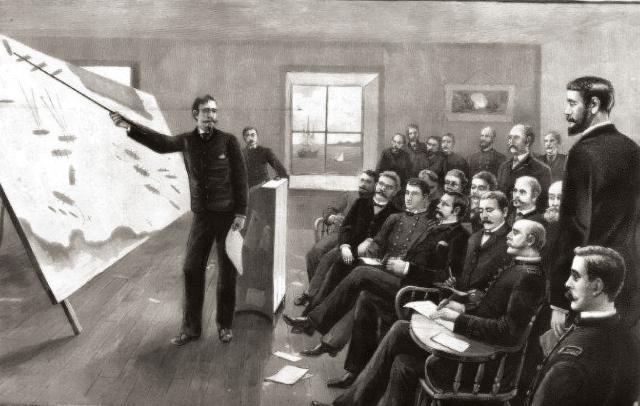

When Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan became the second president of the U.S. Naval War College in 1886, the college was struggling. Officers who had entered in the earliest years expressed doubts about its value. Mahan took stock of where teaching stood and firmly situated history in the center of its efforts to teach strategy. Proceedings in October 1888 published “Address of Captain A. T. Mahan, President of the U.S. Naval War College.” His words anticipated his 1890 classic, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783:

The great warrior must study history. . . . Take some of the points upon which strategy is called to decide. . . . Such points are: the selection of the theatre of war; the discussion of its decisive points, of its principal lines of communication; of the fortresses, or, in case of the sea, the military ports, regarded as a refuge for ships, or as obstacles to progress; the combinations that can be made, considering these features of the strategic field; the all-important point of the choice of the objective. . . . Such, and many other kindred matters, fall within the province of strategy, and receive illustration from history. . . .

Most valuable lessons may be derived also from the study of those wars . . . in which the naval preponderance of one nation has exercised an immense and decisive effect upon the issues of great contests both by land and sea; in which, if I may so say, the Navy has been a most, perhaps the most, important single strategic factor in the whole wide field of a war.

In March 1916, in “Naval Strategy,” Rear Admiral Bradley Fiske distinguished between two kinds of strategy: war and preparation.

War strategy deals with the laying out of plans of campaign after war has begun, and the handling of forces until they come into contact with the enemy, when tactics takes those forces in its charge. It deals with actual situations, arranges for the provisioning, fueling and moving of actual forces, contests the field against an actual enemy, the size and power of which are fairly well known—and the intentions of which are sometimes known and sometimes not. . . .

Preparation strategy deals with the laying out of plans for supposititious wars and the handling of supposititious forces against supposititious enemies; and arranges for the construction, equipment, mobilization, provisioning, fueling and moving of supposititious fleets and armies. War strategy is vivid, stimulating and resultful; preparation strategy is dull, plodding, and for the strategist himself—apparently resultless. Yet war strategy is merely the child of preparation strategy. The weapons that war strategy uses, preparation strategy put into its hands. The fundamental plans, the strength and composition of the forces, the training of officers and men, the collection of the necessary material of all kinds, the arrangements for supplies and munitions of all sorts—the very principles on which war strategy conducts its operations—are the fruit of the tedious work of preparation strategy.

In “Naval War College” in May 1921, the college’s president, Rear Admiral William S. Sims, considered its role in training officers in “strategy, tactics, and administration.” He discussed his experiences commanding U.S. naval forces in Europe during World War I. “The War College cannot be successful without the practical experience that is being continuously developed in the fleet,” he wrote,

for without this experience it would gradually fall behind and tend to become theoretical, or “highbrow,” and might easily become dangerous. . . . The association between the fleet and the college should therefore be as intimate as it is possible to make it. This association cannot be intimate if it is carried on solely by correspondence courses; nor can it be made intimate by the occasional exchange of liaison officers. It can be made intimate only by actual personal intercourse and discussions, that is, by discussions of the teachings of the college by practical fleet men.

At-sea practitioners also were thinking about the strategic value of sea power. In May 1923, Captain Frank Schofield addressed it in “Incidents and Present-Day Aspects of Naval Strategy.” He was in command of the cruiser USS Chester (CS-1) when, in winter 1915, the ship was sent to Africa’s west coast. When a war broke out between competing tribes,

the seagoing tribe stretched its line of canoes seaward and, whenever a venturesome enemy fisherman put to sea, they took him, and whenever an equally venturesome rice trader came out, they took him, too. Then some days later the canoes of these unfortunates would drift on their home shores, fearfully decorated with the headless trunks of their late occupants. So, when the Chester came to the canoe line, it was lolling lazily in the sun with little to do, and security reigned on the fishing grounds and in the village on the shore while the tribe got ready to deliver the coup de grace to their enemies.

It struck me at the time with amazing force that there before me lay all the aims and accomplishments of sea strategy and tactics and sea power in war: To control the use of the sea for one’s self; to deny it to one’s enemies; to bring the pressure of want to the enemy people; to mobilize land forces while sea power held the enemy in check; and, finally, by combined land and sea action to bring the enemy to terms.

Captain Dudley Knox addressed another strategic dimension in his May 1937 article, “Naval Power as a Preserver of Neutrality and Peace.”

The futility of weakness in preserving neutrality, or avoiding war on account of breaches of neutrality, has been thoroughly demonstrated. . . . If there is any solution of the problem set forth it cannot lie in feebleness, but in the opposite direction—in the realm of strong preparedness together with the pacific persuasions of ready force.

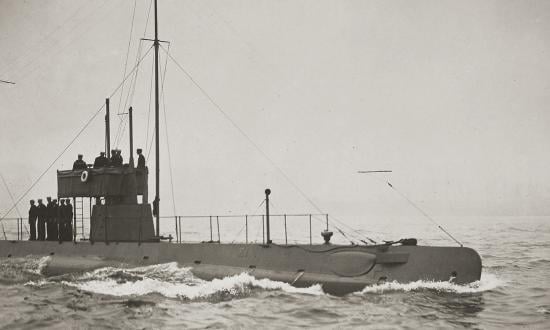

No better proof can be found of the restraining influence of obviously effective neutral power than that given by the vacillations of Germany with respect to ruthless submarining during the World War. . . . The German High Command’s . . . chief concern in debating submarine war on shipping was over which neutrals might thereby be drawn into the war, and especially what force such neutrals might bring to bear as future opponents. . . . With greater strength the neutrals could certainly have maintained their own peace without enduring substantial harm.

When Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz died, Proceedings published in July 1966 a brief biography by Professor E. B. Potter—“Chester William Nimitz, 1885–1966.” Just days after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, Nimitz was appointed commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet.

Admiral Nimitz had four immediate objectives: to restore morale; to divert Japanese strength away from the East Indies; to safeguard U. S. communications to Hawaii, Midway, and Australia; and to hold the line against further Japanese expansion in the Pacific. As Nimitz saw it, all these objectives might be obtained through offensive operations.

At the Battle of the Coral Sea, “The Japanese could proclaim themselves the tactical victors, for their losses were somewhat lighter than the American. But the Americans were clearly the strategic victors. For the first time the Japanese advance had been stopped and turned back.” An innovation that “proved vital to maintaining the strategic momentum of the Central Pacific drive . . . was the mobile service squadrons that moved with the Fleet—ammunitions ships, tenders, repair ships, floating dry docks.”

In December 2014, historian James Hornfischer’s “Rise and Fall of a Seven-Ocean Fleet: The U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 1940–49” framed the country’s strategic vacillation regarding the Navy in this way:

The May 1940 issue of Proceedings contained a list of the [79] new U.S. Navy vessels then under construction. . . . The fleet fielded 243 surface combatants at the time. By August 1945, when hostilities ceased, 932 combat ships were the pulse of a victorious armada that stood astride the world. Four years along, demobilization would cut the register to 192 ships. In 1949, as a Cold War with an erstwhile ally loomed, the cycle of naval bust-boom-bust was beginning anew.

In May 1954, Proceedings published an essay of enduring importance, “National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy,” by Samuel P. Huntington, a political scientist at Harvard University. “The fundamental element of a military service,” he wrote,

is its purpose or role in implementing national policy. The strategic concept of the service . . . is a description of how, when, and where the military service expects to protect the nation against some threat to its security. To accomplish this, a military service must demonstrate that it is deserving of the funds it requires to defend against that threat—funds the nation could otherwise spend elsewhere—and that it is able to organize and use those funds effectively in carrying out its mission.

“Shifts in the international balance of power,” he continued, “. . . must be met by shifts in national policy and corresponding changes in service strategic concepts. A military service capable of meeting [only] one threat to the national security loses its reason for existence when that threat weakens or disappears.”

Huntington argued that Navy strategic thinking was moving toward a “theory of the transoceanic navy, that is, a navy oriented away from the oceans and towards the land masses on their far side.”

Following his 1953–55 tour as Chief of Naval Operations, recently retired Admiral and former President of the Naval Institute Robert B. Carney addressed the “Principles of Sea Power” in September 1955.

National strategy is not an exclusively military term, for it derives from all of the strengths, the pressures, the weaknesses, the capabilities, the limitations of the body politic and its relationships with others, in times of peace and in war.

Echoing Huntington, Carney noted that “sea power is affected by a nation’s financial means, by its manpower in terms of quantity and quality, by its industrial capacity, by its governmental philosophy, by its natural resources, and by the measure of its total power.”

The classical principles of war—the principles of mobility, surprise, concentration, economy of force—all have an obvious place in the use of sea power. And, today, there is another principle emerging—that of dispersal. These principles have strategic as well as tactical meaning, and the strategic application involves functions and policies beyond the scope of military responsibility. . . .

First, every nation depending in any degree upon the use of the sea for its economy and security must ensure to itself that measure of sea control which is commensurate with its needs and resources.

Second, control of the sea is not an absolute function in that it only involves the insurance of the degree of use required, and the denial of specified functional use by unfriendly or inimical nations or groups of nations.

George Fielding Eliot was an American who served in the Australian Army during World War I and as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army Reserve from 1922 to 1933. In between, he lived in Canada and was for a time a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. He also was a prolific writer on defense and strategy who authored half a dozen articles for Proceedings. In November 1956, in “Sea-Borne Deterrent,” Eliot described the strategic risks related to the Soviets’ apparent advantage in the development of intermediate-range ballistic missiles. He suggested that mobile, seaborne weapons and capabilities were the best answer, at least until sufficient numbers of B-52s and intercontinental missiles could deter the Soviet Union.

The cornerstone of our strategy is the deterrent effect on the Soviet mind of our ability to inflict “massive retaliation” in case the Soviets were to engage in any large-scale aggression against our Allies or our own territory or forces. Even temporary impairment of this ability could have a dangerously encouraging effect on Soviet policy. . . .

The principal factors in the Navy’s contribution to the nuclear deterrent are: (1) Fast carrier task forces; (2) Seaplanes (water-based aircraft); (3) Missile-carrying submarines; (4) Mobile logistical support systems; (5) Amphibious capabilities, permitting the establishment and use of temporary plane or missile bases ashore.

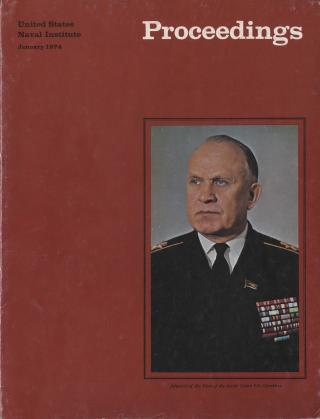

In January 1974, Proceedings took a deep look into the philosophy, strategy, and operations of the Soviet Navy, launching the 11-part series “Navies in War and Peace,” by Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union Sergey G. Gorshkov. The articles, published originally in the Soviet journal Morskoi Sbornik, discussed Russia’s road to the seas, World War I, the building of the Soviet Navy, and that navy in the “Great Patriotic War,” as well as contemporary issues and operations. In the first installment, he wrote:

The qualitative transformations which have taken place in naval forces have also changed the approach to evaluating the relative might of navies. . . . We have had to cease comparing the number of warships of one type or another and their total displacement (or the number of guns in a salvo, or the weight of this salvo), and turn to a more complex, but also more correct appraisal of the striking and defensive power of ships, based on a mathematical analysis of their capabilities and qualitative characteristics.

Each article included commentary from a U.S. flag officer. Following the final essay in November, Vice Admiral Stansfield Turner wrote:

Gorshkov treats as obvious the specifics of how naval presence in peacetime contributes to national purpose, why a great power requires a seagoing capability, and why increasing development of the seabeds demands more naval power. . . . In contrast, we have fallen into the trap of having to explain why we need a Navy in overly specific terms. . . . Admiral Gorshkov has told us that the competition will be stiff. To meet it, we need to understand it. We can be grateful to the Naval Institute Proceedings for starting us in that direction.

In January 1986, the Naval Institute took the rare step of publishing a supplement to Proceedings, a separate document mailed with every issue: The Maritime Strategy, under the byline of Chief of Naval Operations Admiral James D. Watkins, but in practice the work of numerous officers and civilians. As the document explains,

The Maritime Strategy is firmly set in the context of national strategy, emphasizing coalition warfare and the criticality of allies, and demanding cooperation with our sister services. Moreover, The Maritime Strategy recognizes that the unified and specified commanders fight the wars, under the direction of the President and the Secretary of Defense, and thus does not purport to be a detailed war plan with firm timelines, tactical doctrine, or specific target sets. Instead, it offers a global perspective to operational commanders and provides a foundation for advice to the National Command Authorities. The strategy has become a key element in shaping Navy programmatic decisions. It is of equal value as a vehicle for shaping and disseminating a professional consensus on warfighting where it matters—at sea.

In April 1988, “The Maritime Strategy and the Next Decade,” Ronald O’Rourke’s Prize Essay looked ahead.

Much of what the Navy lost during the 1970s in the way of personnel strength, readiness, and overall capability was recovered and surpassed by its achievements during the 1980s The 1980s are drawing to a close, however, and not just in a chronological sense. . . .

The public consensus for the rebuilding effort, which underpinned both [President Ronald] Reagan’s and [John] Lehman’s efforts, began to dissipate long before Lehman’s departure and is now essentially gone. In all these ways, the 1990s could well prove to be a very different era for the Navy. Indeed, the resignation of Lehman’s successor, James Webb, after only ten months in office, can be seen as an early signal of more difficult times to come. . . .

For the past several years, The Maritime Strategy has served the Navy as: A guide for rationalizing Navy plans and programs; a persuasive framework for Navy funding requests; a vehicle to help deter the Soviets, [and] a statement of reassurance to the allies. . . .

In meeting the challenges of the 1990s, a more fully developed Maritime Strategy might prove to be of substantial value.

“The decade of the 1980s was a transformative one,” former Secretary of the Navy John Lehman wrote, looking back in July 2015’s “‘We Win and They Lose’: The U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 1980–89.”

It began with the continued ascendance of the Soviet Union and Admiral Sergey Gorshkov’s Soviet Navy. It finished with the dismantling of the Iron Curtain, the Warsaw Pact, and the Berlin Wall, and with rust forming on the Soviet Union’s newly laid-up warships.

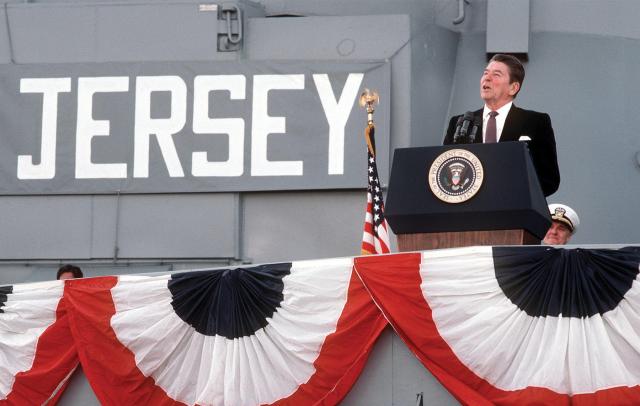

At the recommissioning of the USS New Jersey (BB-62) in December 1982, President Reagan forcefully declared that “maritime superiority for us is a necessity. We must be able in time of emergency to venture in harm’s way, controlling air, surface, and subsurface areas to assure access to all the oceans of the world. Failure to do so will leave the credibility of our conventional defense forces in doubt.” And half a decade earlier he had summarized what his policy toward the Cold War would be: “We win, and they lose, what do you think about that?”

The strategic triumphalism of victory in the Cold War did not last long. In November 1992, the Naval Institute published a Navy–Marine Corps white paper on strategy, “. . . From the Sea,” as it had the 1986 Maritime Strategy six years earlier. The end of the Cold War brought about a period of strategic uncertainty evident in the white paper’s intent to be a “broad assessment of the future direction of our maritime forces” rather than the clear, offensively minded statement the 1986 document was.

The fundamental shift in national security policy was first articulated by [President George H. W. Bush] at the Aspen Institute on 2 August 1990. This new policy is reflected in the President’s National Security Strategy and the “Base Force” concept developed by the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

This National Security Strategy has profound implications for the Navy and Marine Corps. Our strategy has shifted from a focus on a global threat to a focus on regional challenges and opportunities. While the prospect of global war has receded, we are entering a period of enormous uncertainty in regions critical to our national interests. . . .

Our Naval Forces will be full participants in the principal elements of this strategy—strategic deterrence and defense, forward presence, crisis response, and reconstitution.

Retired Marine Corps Lieutenant General Bernard Trainor—historian, analyst, author, New York Times columnist, and veteran of the Korean and Vietnam Wars—helped to put the Cold War’s results and the new era’s changing international security complexion in perspective in February 2008. In “A Triumph in Strategic Thinking,” he wrote:

The NATO strategy, concept, and planning documents turned out in the 1960s, ’70s, and early ’80s amounted to passive paralysis. . . . With the emergence of an offensive strategy in the 1980s, a change in mindset was energized by concurrent dramatic advances in American technology, especially in C4ISR and weapon systems, that were rapidly offsetting Soviet numerical and material superiority in Europe. No lesser light than the USSR Chief of the General Staff, Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov warned that American superiority was shifting the “correlation of forces” in NATO’s favor. He called the phenomenon a “military technological revolution.” By the end of the decade the military threat from the Soviet Union was consigned to the dust bin of history and, with it, the Cold War.

Vice Admiral Sandy Winnefeld picked up where Trainor had left off. His July 2008 article, “Maritime Strategy in an Age of Blood and Belief,” opened with a sweeping perspective on the challenges with which any new strategy would have to contend:

As the 20-year fog of the post-Cold War transition lifts, a 21st-century pattern of international affairs is coming into sharp focus. The classic ideological feud between capitalism and socialism has given way to new dynamics that are remaking the international system: rising ethno-nationalism, violent religious extremism, globalization, scarcity of energy and food resources, and concerns over immigration and climate change.

Nowhere is this more true than Europe, Eurasia, and Africa, where these factors are widespread and intensifying, with increasingly disruptive effects. . . . In an age dominated by blood and belief, the need is rising again for a more robust set of U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard forces to operate in these vast and complex regions.

Robert O. Work, as Under Secretary of the Navy, published “The Coming Naval Century” in May 2012, examining the issues and the bottom line: “The Navy and Marine Corps will be the long arm of a National Fleet central to U.S. military power.”

This Fleet and its network would make short work of any past U.S. Fleet—and of any potential contemporary naval adversary. It will only get better for the Navy–Marine Corps team. . . . Samuel P. Huntington . . . argued that the service with the strategic concept and organizational structure most able to answer the dominant national-security challenges . . . was the one most rewarded when it came time to allocate the country’s scarce national resources.

If Huntington is right—and I believe he is—then as we go forward, the nation will inevitably allocate the resources necessary to implement our strategic concept and organizational construct, as long as we articulate them and can back them up with tangible actions.

Our destiny is, thus, in our own hands. Together we must update the Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower to better refine our strategic concept, and then tirelessly explain how the combined capabilities of the Navy–Marine Corps team, the Coast Guard, Military Sealift Command, Maritime Administration, and Merchant Marine form a National Fleet with a broad range of capabilities and capacities absolutely vital to our national security.

The waning years of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan saw the Navy’s focus shift from supporting land conflicts in Southwest Asia once again to maritime conflicts.

In November 2020, Navy Lieutenant Commander Ryan Hilger identified a major weakness in the Navy’s strategy development process. In “The Navy Must Rebuild the Ecosystem of Strategy,” he began: “In the span of a generation, the U.S. Navy forgot how to develop warrior-admirals. . . .

Who in the Navy is responsible for strategy? It’s complicated. . . . As one officer noted in a 1970 internal memo: “Practically the entire OpNav organization is tuned, like a tuning fork, to the vibrations of the budgetary process. . . . There is a vast preoccupation with budgetary matters at the expense of considering planning, or readiness or requirements, or operational characteristics or any of the other elements contributing to the ability of the Fleets to fight.”

The environment has changed little.

Close on Hilger’s heels, the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard released, in December 2020, the triservice maritime strategy, Advantage at Sea. In June 2021, Heather Venable, a professor at the U.S. Air Command and Staff College, wrote bluntly about “The New Maritime Strategy’s Backward Step”:

Advantage at Sea is not an actual “strategy,” and this troubling reality is emblematic of the “strategic atrophy” identified by the 2018 National Defense Strategy. Advantage at Sea is more like a smorgasbord of operational ideas only loosely connected to a vague end state. Like many concepts proposed by the U.S. military, it lacks a coherent vision of how to connect ends, ways, and means. More specifically, its most resounding theme—all-domain maritime power—is an uncreative step backward, as other military services have been stressing the full integration of domains for the past five years.

The Naval Institute launched the American Sea Power Project in January 2021 to provide the impetus for development of just such a coherent strategic vision. In his February 2021 contribution to the project, “Great Responsibility Demands a Great Navy,” Naval War College strategy professor James Holmes warned of the dangers of a mismatch between means and ends:

What Washington must not do is set ambitious goals while neglecting to amass the means to achieve them. U.S. leaders have transgressed before. In 1943, the political commentator Walter Lippmann reproached past presidential administrations for taking on vast commitments in the Pacific Ocean after the 1898 Spanish-American War but failing to construct a navy mighty enough to defend them. . . . Ambition unbacked by physical might had invited Japanese aggression. Future administrations must not repeat their forebears’ strategic malpractice.

Kori Schake, the director of foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, also contributed to the American Sea Power Project. In “Strategic Failures Are Often Failures of Imagination,” she wrote of the interwar period and the Washington Naval Treaty:

Britain’s failure was, ultimately, one of imagination; it could not imagine itself as other than what it had always been, even as Washington and especially Tokyo imagined new ways to fight. The U.S. military innovated before the war just enough to hold its own until those economic advantages could be brought to bear. Today, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps should ask themselves whether the current force more closely approximates the one that burst into being during the Washington naval accords years—or the Royal Navy that remained so beholden to its past successes and ashamed of its failures that it stifled the creativity and experimentation needed to face the looming challenges.

Discussion and understanding of strategy in all its varieties—naval, military, maritime, and grand—in the Sea Services has waxed and waned, often in proportion to (and confused with) the size of the fleet. But the discussions in the pages of Proceedings have helped keep the eyes of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard on the strategic ideal nonetheless, ensuring a permanent and substantive resource for those who seek to understand, develop, and implement maritime strategies in the coming years.