Consider a war in the western Pacific—one fought along the lines of the “War in 2026” scenario—in light of the current posture of U.S. forces in Okinawa, Japan. For III Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF), the fight probably would be short:

China’s long-range missiles and weapons rained down on Okinawa, attempting to knock U.S. forces off the board to prevent their intervention in China’s invasion of Taiwan. III MEF was taken by operational surprise. Garrison command posts were among the first targets. These command-and-control (C2) nodes were destroyed, and the commanders and staffs operating from them were immediately killed.

Alternate command posts, thrown together on the fly by the surviving leaders, could not build a common operational picture (COP) or establish command and control over the forces remaining. Units struggled to aggregate and failed to deploy to key locations in time to interdict Chinese forces—if they managed to deploy at all. Many Marine Corps aircraft were destroyed on the tarmac. Some Marines focused on evacuating their families and didn’t report to their fighting positions in time to influence the campaign. And those families created an operational drain on ever dwindling air- and sealift. With III MEF destroyed as a warfighting organization, the Marine Corps failed to contribute to the fight. America’s “force in readiness” proved to be anything but.1

Consider another possibility:

China’s long-range fires rained down on Okinawa—but III MEF was ready. Damage and casualties were sustained, but underground and hardened command posts withstood the missile barrage. Other key nodes, dispersed across the Ryukyus and continually mobile as a matter of course, survived and functioned despite being above ground.2 These command centers, fully manned 24/7, maintained a COP and enabled decision-making.

Critical forces had deployed to key maritime terrain ahead of the fighting, maintained the enemy at Tactical Situation 1, and fed targeting data to joint and allied kill webs.3 There were no families to evacuate, as families had wisely been kept out of the weapons engagement zone (WEZ) and remained safe in the continental United States. Consequently, lift remained available to flow forces and matériel into and around the area of operation. Because it was in a ready-and-waiting fighting stance, III MEF and the Marine Corps proved their value as stand-in forces throughout the campaign, helping to win the war.

Each outcome is possible.

Senior Department of Defense officials continue to suggest a war in the western Pacific could arrive in only a few years.4 But U.S. forces in general, and III MEF in particular, are not in a fighting stance.

This means the second outcome will be less likely unless the Marine Corps is funded for and willing to make the hard decisions now that will fully prepare III MEF. “Divesting to invest” has freed resources to permit the Marine Corps to set III MEF on a course for optimization. But those resources will not be enough to be ready for war with China. In its current state, III MEF is not postured to “fight now.”5 Put another way, it is not in “a boxer’s stance.”6

Forward Deployed—or Forward Garrisoned?

III MEF is the only unit of its kind permanently deployed forward to be a combat-credible stand-in force for the commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. The posture of III MEF and other U.S. forces will be the most decisive factor in deterring China or preventing a fait accompli should conflict occur.7 But despite its impressive warfighting capabilities and transformation in keeping with Force Design 2030, III MEF’s operational posture is that of a garrison force. So long as that remains true, it will not be sufficient to the tasks set before it.

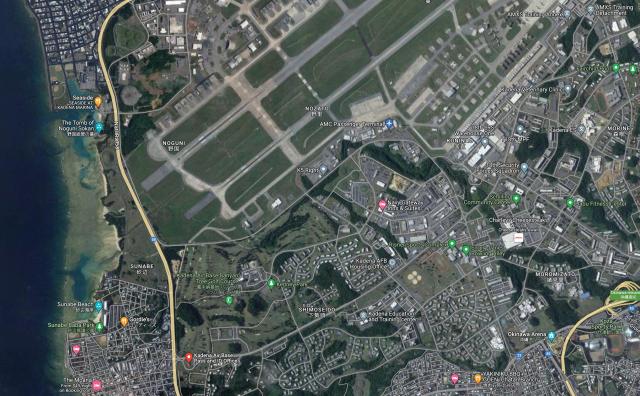

Contrast Marine Corps deployments to Iraq or Afghanistan with those to Okinawa. In the first two countries, deployed Marines brought their kit, not their families and household goods. They lived in hardened facilities with intentional force protection, not barracks and vulnerable base housing. They commanded out of covered and concealed operations centers, both static and mobile, rather than administrative buildings that could be geographically located in seconds with a Google search. Deployed combat operations centers were fully staffed 24/7, with COPs that enabled immediate decision-making by commanders and coordination by watchstanders.

While III MEF may be advertised as the “fight now” force, it is not presently postured as one.8 Marines do not deploy to Okinawa—they move there, as to a duty station rather than a fighting position.9 Even Unit Deployment Program participants live and operate in a way that largely resembles garrison life—living in barracks and going to the field for exercises, rather than preparing to fight 24/7, as one would expect when combat is anticipated.

This is a far cry from the boxer’s stance U.S. forces should aspire to.10 If the Marine Corps wants its premier stand-in force to be ready to fight at a moment’s notice, it must operationalize III MEF in every possible way. Only by ensuring forces in the first island chain are ready to fight—now—will III MEF fulfill its strategic promise.

Squaring Off

Adopting the fighting stance can be achieved only with appropriate resources and decisions about the service’s role ahead of conflict. And obtaining those will require the following efforts:

Field littoral connectors quickly. These vehicles must be an essential element of deploying, maneuvering, and sustaining stand-in forces across key maritime terrain. But the Marine Corps presently lacks a shore-to-shore connector to enable expeditionary advanced base operations. Instead, it must rely on aircraft to rehearse and carry out this mission.11 Employing aircraft for assault support remains a valid option for rapid insertion of forces, but it assumes great risk given enemy sensors and kill webs, demands sortie generation at the expense of other missions, and creates maintenance risks. Surface connectors can move matériel and equipment at a volumetric rate aircraft cannot match.

The Landing Ship Medium (LSM) program will provide the Marine Corps the amphibious connectors it needs to maneuver in the littorals, but at an unacceptably slow production rate. Service leaders regularly note that 35 LSMs will be required to meet stand-in force mission requirements.12 But the Navy’s fiscal year 2024 budget submission proposes construction of only the first LSM—in May 2026, too late for the Phase III scenario (and many others).13 As a bridge, the service has leased an offshore support vessel to test the Stern Landing Vessel (SLV) concept. However, the procurement plan even for SLVs is inadequate; at the start of this conflict, at most three would be in theater.14

While fiscal constraints cannot be wished away, the issue boils down primarily to funding. Combatant commanders and Congress resoundingly endorse the LSM as the connector solution for stand-in forces.15 But ship production will accelerate only with significant pressure from the Commandant of the Marine Corps and the Chief of Naval Operations and substantially increased funding.

Build and harden underground command centers and barracks. Day to day, Marine Corps forces in Okinawa operate in above-ground, garrison command posts and live in barracks that an adversary can readily find using open-source tools and include on a target list for the opening moments of a conflict. In various wargames, Chinese devastation of U.S. bases has consistently resulted in substantial degradation of U.S. capabilities.16

III MEF command posts and living quarters should be hardened to withstand anticipated fires. To be feasible, this would mean developing underground facilities or taking advantage of existing ones to put earth between command centers and incoming munitions. Marines should not wait for the shooting to start to move to these centers and quarters but should live and operate out of them as standard operating procedure. A fully developed COP should enable around-the-clock watchstanders to exploit III MEF’s war-fighting potential.

Employ mobile, dispersed alternate command posts. Despite the protection of many meters of rock and soil, underground primary command centers might not enable command and control in the face of a sustained barrage of long-range precision fires. China claims it has developed conventional bunker-busting munitions.17

To provide redundant C2, III MEF will need to employ mobile and dispersed alternate command posts that use cover, concealment, dispersal, and mobility to maximize survivability. The distribution of commanders, C2 systems, and staffs would be similar to that of main, forward, and jump command posts.

Implement forward deployment and basing at key maritime terrain. Forces not in position to fight now will be hard pressed to get where they need to be after conflict begins. In wargaming, both aerial and amphibious attempts to stand forces into the WEZ after conflict began have ended in abject failure.18 Waiting to deploy until the fighting starts cedes to China a potentially decisive first-mover advantage.

To mitigate this, appropriate Marine Corps forces should be deployed forward continuously in key locations—starting immediately—so they can meaningfully contribute to reconnaissance, counterreconnaissance, kill-web completion, and sea denial, in keeping with A Concept for Stand-In Forces. Sensors, shooters, and other stand-in force elements should be deployed in the field—on the move as they will be in wartime, their capabilities online and contributing to the deterrent posture and combat credibility of the joint force. These units will conduct a relief-in-place only when new units arrive to assume their duties.

Forward facilities at key maritime terrain also might be necessary. The Japan Ground Self-Defense Force operates out of new bases at critical islands in the first island chain.19 Establishing dual-use agreements could mitigate the cost to U.S. forces, but co-occupying facilities also could create space constraints for the Japanese forces. Sharing the locations but developing U.S. infrastructure at them will better enable continual deployments to operate, maintain, and sustain themselves in a contingency.

Deployments don’t include families. For good and obvious reasons, dependents never deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan with their Marines—neither should dependents deploy into the first island chain. Okinawa is within the WEZ of a preponderance of China’s antiaccess and area-denial capabilities, and today’s base housing straddles key targets such as airfields and C2 nodes. These arrangements put families into what will become the beaten zone of long-range precision fires.20 This creates moral, ethical, psychological, and political risk when hard decisions must be made regarding lift and sustainment priorities. Families could impose an unacceptable tax on strategic lift needed to push forces and matériel into theater.

If evacuating families becomes impossible, this would create an additional and punishing demand for the limited supplies available to sustain the fight. In 1940, the Department of the Navy ordered all dependents out of China when storm clouds began to brew between the United States and Japan.21 The United States would be wise to order dependents from Okinawa now if officials truly believe a war with China is likely.

Build hardened air shelters. While there are some hardened air shelters in the first island chain, the number is insufficient if the goal is to protect the preponderance of U.S. air power. For III MEF, this protection is critical, as 1st Marine Aircraft Wing is the only organic capability for the MEF commander to project Marine combat power across the theater.

Chinese munitions would still put these aircraft at risk, but each additional shelter would require China to employ an individual, unitary warhead to target it. In addition, with more hardened air shelters, a submunition-armed single missile would not be able to destroy multiple aircraft.22 Such measures should reduce the overall loss of aircraft from missile attacks. While physical space for U.S. bases remains at a premium in Japan, withdrawing families now would allow repurposing of base housing and dependent support facilities for hardened air shelters and other requirements.

Consider Korea part of the first island chain. The Republic of Korea (ROK) is not an island, but it is a key point along the chain, which is usually represented as starting at the Philippines, going north to Taiwan, northeast to Okinawa, and connecting to Kyushu before terminating at the rest of the Japanese Home Islands. This leaves a noteworthy gap in the Korea Strait and ignores the fact that the ROK—fully inside the chain—is geographically closer to China than Japan.

Integrating Korea into planning now would offer numerous operational and strategic advantages. While most U.S. forces in the ROK support Combined Forces Command to defend South Korea from North Korean aggression, the deepening trilateral security ties among the United States, Japan, and the ROK open new possibilities for an integrated regional security architecture.23

Because prepositioning matériel for III MEF in Japan is sometimes not feasible, suitable, or acceptable, war stocks might need to be placed, unhelpfully, well outside the first island chain. Prepositioning stocks instead in Korea might be better.

Integrating the ROK fully also could support III MEF’s obligations under the Defense Posture Review Initiative, which requires the reduction, over time, of Marine Corps forces on Okinawa, with many destined for Guam.24 This will be operationally unsuitable, however, because it will move such forces more than 1,400 miles from Okinawa and into the second island chain. If the forces must leave Okinawa, the ROK would be an operationally better destination than Guam.

Get III MEF in a Fighting Stance

Despite the challenge, if something like the “War in 2026” scenario comes to pass, taking the steps required to put III MEF in the stance to support the joint and combined fight against China will have been worth the effort.

Deployed to key maritime terrain and with littoral mobility and prepositioned munitions, III MEF would be able to identify and track People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) vessels for naval, joint, and allied commanders, enabling kill webs within the first island chain, and preventing Taiwan’s isolation.25 Equipped and placed in this way, III MEF could target PLAN surface forces and submarines that might otherwise challenge sea lines of communication.26

Ultimately, the proposed changes would flip the script: Rather than seeing U.S. Marines hemmed in on Okinawa (a risk open-source wargames have noted), the Marines would hem in PLAN forces within the first island chain, prevent the isolation of Taiwan, and buy back precious time for the joint force to mass within the decisive space.27 Prepositioned forces with prestaged critical munitions and austere, mobile, redundant, and hardened fighting positions would preserve III MEF as an invaluable fighting force.

But Marines do not, at present, deploy to Okinawa. They move there and live there in the same way they do in Europe. III MEF remains postured as an overseas garrison force.

To continue along this path is folly. The Marine Corps can realign the posture of forces to that of a true, combat-credible, and ready-to-fight force. To do this will require deploying Marines to Okinawa without their families, establishing them persistently on key maritime terrain, and making all the other changes that a force deployed in range of the enemy’s fires must make. The Marine Corps must get III MEF into a fighting stance.

1. Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, 9 January 2023).

2. Stew Magnuson, “Army Looks to Disperse Command Posts to Boost Survivability,” National Defense Magazine, 22 October 2020.

3. CDR Bryan Leese, USN, “Living in TACSIT 1,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 143, no. 2 (February 2017).

4. Idrees Ali and Ted Hesson, “U.S. Four-Star General Warns of War with China in 2025,” Reuters, 1 January 2023.

5. III Marine Expeditionary Force, “III MEF Booklet,” Marines.mil, 22 October 2021.

6. Gen Joe Dunford, USMC, “Maintaining a Boxer’s Stance,” Joint Force Quarterly 86 (Third Quarter, 2017).

7. Michael Kofman, “Getting the Fait Accompli Problem Right in U.S. Strategy,” War on the Rocks, 3 November 2020.

8. U.S. Marine Corps, “Fight Now: III Marine Expeditionary Force,” youtube.com, 19 February 2021.

9. Lt Col Brian Kerg, USMC, “Get Families Out of the First Island Chain,” Marine Corps Gazette 107, no. 9 (September 2023): 42–45.

10. Dunford, “Maintaining a Boxer’s Stance.”

11. Albert Carls, “Stand-in Force Exercise: 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines Air Insertion,” www.dvidshub.net.

12. U.S. Marine Corps, Force Design 2030 Annual Update (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, June 2023), 9.

13. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Medium Landing Ship (LSM) (Previously Light Amphibious Warship [LAW]) Program: Background and Issue for Congress, Congressional Research Service, 7 August 2023.

14. Megan Eckstein, “Marines to Test Out First Stern Landing Vessel at Project Convergence,” Defense News, 7 September 2023.

15. Robert Work, “Marine Force Design: Changes Overdue Despite Critics’ Claims,” Texas National Security Review 6, no. 3, Summer 2023.

16. Cancian et al., The First Battle of the Next War, 112–14.

17. Michael Peck, “They’ve Done It: China’s Mad Scientists Have Created Their Own ‘Mother of All Bombs,’” The National Interest, 3 October 2019.

18. Cancian et al., The First Battle of the Next War, 130.

19. “China-wary Japan Establishes New Military Base on Southwest Ishigaki Island,” The Mainichi, 16 March 2023.

20. Mark Wortman, “The Children of Pearl Harbor: Military Personnel Weren’t the Only People Attacked on December 7, 1941,” Smithsonian Magazine, 5 December 2016.

21. ATC (AW) Robert O’Dell, USN, “Rediscovering the Asiatic Fleet,” Naval History 12, no. 6 (December 1998).

22. Cancian et al., The First Battle of the Next War, 81.

23. Jim Garamone, “Japan, South Korea, U.S. Strengthen Trilateral Cooperation,” Department of Defense News, 18 August 2023.

24. Congressional Research Service, “U.S. Military Presence on Okinawa and Realignment to Guam,” In Focus (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2019).

25. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “Preparing for the Future: Marine Corps Support to Joint Operations in Contested Littorals,” Military Review 101, no. 3 (May–June 2021), 204–5.

26. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “Marines Will Help Fight Submarines,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 11 (November 2020).

27. Cancian, et al., The First Battle of the Next War, 129–31.