Tonga, an island nation in the Pacific, lost almost all contact with the rest of the world for five weeks in early 2022. The eruption of an underwater volcano severed its only submarine cable, effectively halting financial transactions, trade, and tourism. The only outside contact was provided by a weak satellite signal with an hours-long queue.1 Devastating both Tonga’s economy and its people, the blackout also proved the vulnerabilities of undersea cables.

Now, imagine a similar scenario involving Guam, but during a conflict. Home to a critical U.S. military contingent, this U.S. territory remains lightly defended, especially considering “war games often predict early and sustained Chinese missile strikes on Guam” in the event of military conflict.2 A coordinated severing of the cables connecting Asia, Hawaii, and the rest of the United States could cause an information blackout that could devastate Guam’s economy and significantly handicap the U.S. military’s regional capabilities and command and control.3

Consider a second, gray zone scenario: Chinese fishing vessels coordinate a cable-severing operation and “inadvertently” damage the undersea cables connecting Taiwan to the outside world. The island’s internet-reliant infrastructure, communications, and trade snap to a halt as satellite internet is wholly overwhelmed, and a quasi blockade involving Chinese fishing vessels and its maritime militia obstructs private industry’s repair vessels. To provide support, the United States is faced with the strategic dilemma of initiating military action against ostensibly nonmilitary targets if diplomatic efforts fail to bring an acceptable resolution. After a blackout lasting several weeks, China offers to fix the issue and fully integrate Taiwan with the mainland, effectively consuming the island without a direct military confrontation.

As basic necessities increasingly demand internet connections, damage to these undersea cables threatens both national and global security in a way the United States has not yet determined how to mitigate. However, the U.S. Coast Guard could be a balanced, high return-on-investment solution. By designating the Coast Guard as the lead agency for the undersea cable risk, the United States can align strategic and tactical preparations with operational capability to better prepare for and respond to potential threats. As the leader of the Global Maritime Operational Threat Response (MOTR) Coordination Center, the Coast Guard should identify specific organizational responsibilities and develop plans to counter the undersea cable threat instead of treating the issue as one requiring only a general threat response.4

High Risk, Low Security

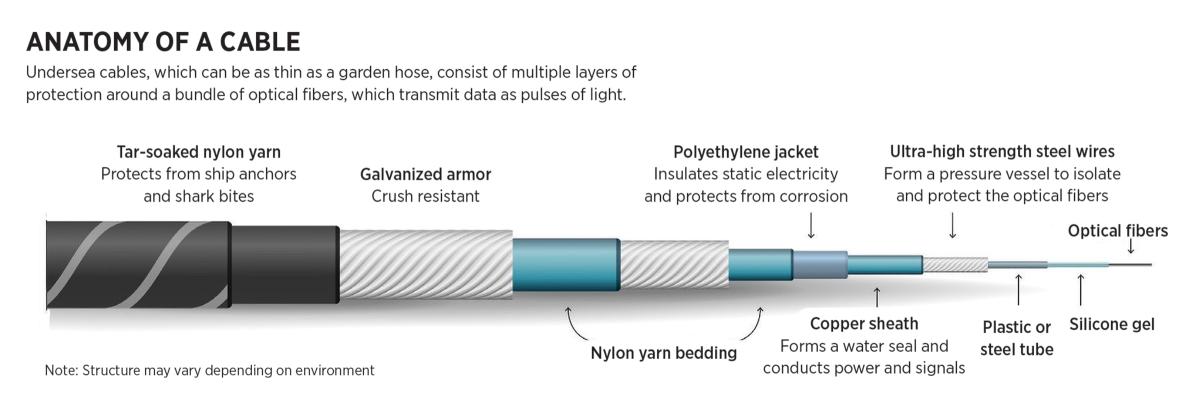

Undersea cables carry about 95 percent of the world’s transnational internet traffic and support trillions of dollars in daily financial transactions.5 They are largely taken for granted, however, particularly as new satellite constellations such as Starlink are developed. Satellite internet is critical, but its weak signals and limited capacity mean it will never be a sufficient alternative.6 The complex international politics of the ocean further cloud the issue and create a veil of secrecy exploited by bad actors worldwide. Though discussed in limited circles, issues in the maritime space usually garner public attention only after serious incidents or disasters.

Unintentional physical damage is the most common hazard to undersea cables.7 Within the current network of more than 500 cable lines, more than 100 cable breaks occur annually, primarily because of fishing and anchor gear damaging and/or pulling up cables. Natural disasters also pose a threat.8 The Taiwan earthquake in 2006 disrupted business and communication throughout East and Southeast Asia.9 The repairs required almost half the cable-servicing vessels around the world.10

Unintentional electronic threats pose perhaps the least danger to undersea cables but can expose potential vulnerabilities.11 Examples include software bugs involving cable remote-management or landing-station systems. Though correctable with timely software updates, electronic vulnerabilities could be exploited by bad actors.

Intentional threats, whether physical or electronic, are commonly treated as black swan events, but the coordinated sabotage of the Nord Stream pipeline in September 2022 underscores their reality.12 Both historic wartime examples and recently severed cables in northwest Europe, Vietnam, and Taiwan show what a targeted, yet deniable, physical attack might look like.13 A cable break caused by a shipping container in the Mediterranean in 2008 temporarily halted nearly all U.S. military communications and remote operations in Iraq.14

One consideration is the attempted decoupling of U.S. adversaries from existing undersea cable networks. China has become a serious competitor and is using its state-sponsored Digital Silk Road to decrease its reliance—and that of other countries—on U.S. undersea cables.15 The threat of China intentionally severing U.S. cables while using domestic networks to partially shield itself and others from collateral harm is increasingly concerning.

Diffuse Authority

For the United States, responsibility for responding to threats to undersea cables below the strategic level is spread among an amalgam of agencies and involves a notable absence of operational leadership. At the strategic level sits Team Telecom, chaired by the secretaries of the Departments of Homeland Security (DHS) and Defense (DoD) and the Attorney General and advised by other cabinet-level leaders.16 This team has taken decisive action to support U.S. national security interests through undersea cable contracts and licensing, but efforts at the strategic level alone are not enough to mitigate U.S. and allied vulnerabilities.17

At the tactical and operational levels, the United States has no coherent response vision. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is responsible for licensing cable landings in the United States, but it has called for a lead agency in undersea cable protection and response.18 An internal working group called for the FCC to “liaise with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which serves as the lead agency for critical infrastructure protection in the telecommunications sector.”19 DHS is officially responsible under the National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP), but the organization’s lack of publicly published acknowledgment or plans, which are arguably necessary given the complex, multinational nature of the problem at the intersection of public and private interests, indicates absence of preparation.20

The United States’ cable security fleet (CSF) consists of two subsidized, on-call cable vessels. The creation of the CSF under the Maritime Administration was a significant step forward, but as discussed in an October 2022 Proceedings article, its future remains unclear.21 The CSF’s seemingly standalone nature, uncertain future, and limited assets make its ability to coordinate a prompt and appropriate response questionable.

A recent Congressional Research Service (CRS) report highlights the need for a comprehensive solution. While discussing DHS’s planning deficiencies, it also recommends Congress consider appointing “a lead agency to coordinate undersea telecommunication cable security.”22 This CRS report and several U.S. think tank analyses underscore the international nature of this vulnerability.

A Comprehensive Solution

For such a comprehensive issue, a lead agency must be multifaceted. As a maritime agency, the Coast Guard has domestic and international authorities in both peace and war. It is integrated into DHS, DoD, and the intelligence community.

The Coast Guard has a rich history of supporting maritime commerce and infrastructure.23 It is responsible for the Marine Transportation System (MTS) under the NIPP. While the current Maritime Commerce Strategic Outlook includes electronic systems supporting vessels and port infrastructure, under the MTS, undersea cables are also information technology infrastructure.24 The Coast Guard has acknowledged this nexus while expanding into the cyberspace domain. Its Cyber Strategic Outlook includes undersea cables within its definition of the MTS.25 Furthermore, because DHS is the responsible agency under the NIPP, the Coast Guard should embrace this leadership role.

A maritime threat issue requires leadership from a maritime organization, and the Coast Guard is the only service or agency with the right balance of capabilities and authorities. And while the MOTR plan provides excellent single-crisis coordination and response, the MOTR community does not plan for, train for, and respond to long-term strategic threats such as those involving undersea cables.26 This demands specific agency designation, preparation, and response capabilities. The Coast Guard offers the best, most practical solution.

Potent Operational and Organizational Capabilities

On the water, the Coast Guard’s specialized cutters and crews provide a range of capabilities. On a daily basis, cutter commands and crews apply legal authority in complicated jurisdictional environments, solve novel problems during search-and-rescue and other missions, and coordinate on-scene efforts with numerous agencies with differing authorities. Because of the wide range of scenarios facing undersea cable disruption and response, and especially considering the unique circumstances surrounding public and private responsibility for undersea cables, the Coast Guard offers the most practiced mariners capable of leading a response at the scene.

The Coast Guard’s shoreside functions are similarly tailored for this leadership role—it has premier experts in both maritime response and investigation. Any Coast Guard operation also involves a group of specialists coordinating logistics from shore. Response experts are literate in cyber threats and operational conditions, trained under the Incident Command System (ICS), accustomed to applying skills and authorities across agencies, and experienced in planning emergency responses and coordinating multinational efforts. In addition, the Coast Guard regularly investigates maritime incidents, both in its law enforcement capacity and during official inquiries into large-scale events, such as the recent pipeline disruption off Southern California.27 The Coast Guard is well positioned at the intersection of several commercial, military, and intelligence communities.

The value of the Coast Guard’s independent representation in the intelligence community merits emphasis. The unique demands of such a complicated subject as the undersea cable threat and the catastrophic danger of cable destruction or sabotage require high-level coordination, specifically involving intelligence collection and threat identification.

While the Coast Guard is interoperable with DoD forces for most military operations, especially during war, it is a peacetime law enforcement agency. This has proved particularly effective in the Pacific, where the Coast Guard has embarked on a relationship-building campaign.28

Imagine the 2006 Taiwan earthquake under Coast Guard leadership. The Coast Guard could have immediately coordinated with private industry and developed a thorough understanding of the necessary logistics and timelines. Japan and the Philippines could have assisted with this planning because they are at either end of the severed cables. This early coordination would have informed and tailored diplomatic efforts. Alongside partner nations, a Coast Guard national security cutter and a seagoing buoy tender with an embarked law enforcement detachment could arrive with repair vessels to provide a tactful counter to the Chinese vessels, as well as enhanced logistical support for the repair efforts.

In a similar future situation, the national security cutter’s intelligence capabilities would likely prove invaluable. Seagoing buoy tenders could enhance logistical support capabilities and augment the law enforcement presence. While still a dangerous international situation, the Coast Guard’s prompt response could help navigate the crisis and avoid escalation.

Initial Steps

The United States cannot continue to neglect cable security, especially in the current decade of increased competition and gray zone conflict. The following actions would help lay the groundwork for a coordinated threat reduction:

1. Senior Coast Guard leaders should consider vulnerabilities and possible scenarios vis-à-vis national security and weigh the gain of a practiced response.

2. The Coast Guard should establish a working group to examine requirements to assume lead responsibility for undersea cable threat response. The theme should be operational success in both gray zone and wartime circumstances. At a minimum, this group should:

• Determine requisite information and its sources for proper response planning

• Determine the number of specialized U.S. ships that could contribute to repair operations, including government and private-sector assets

• Examine integration points with other agencies and the private sector

• Propose internal Coast Guard responsibilities

• Recommend an initial plan of action to establish Coast Guard leadership in undersea cable response

3. The service should offer working group findings and recommendations to Team Telecom with the goals of formalizing the Coast Guard’s leadership, defining integration points with other agencies, and identifying avenues for requisite funding.29

Threats to the undersea cable network are incredibly vast and complex, and as adversary gray zone actions and posturing become more frequent, the United States cannot afford to rely on only the thinly stretched private sector. The exposure may be small, but it is growing, and the consequences of poor response could be grave. Undersea cable vulnerability can no longer be overlooked, especially when the cost of entry at the federal level involves little more than assigning the mission to an existing, high-performing service—the U.S. Coast Guard.

1. Mary Lyn Fonua, “Learning to Talk Again: Life without Internet in Tonga," Science X Network, 5 February 2019; and Meaghan Tobin and Marian Kupu, “Four Months Offline: Post-Quake, Many Tongans Are Still Without Internet,” Rest of World, 30 May 2022.

2. “Guam, Where America’s Next War May Begin,” The Economist, 2 April 2023.

3. Rob Verger, “This Typhoon-Resistant Facility in Guam Will Power the Tubes that Give Us the Internet,” Popular Science, 2 July 2019.

4. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Global MOTR Coordination Center (GMCC).”

5. Jill C. Gallagher, “Undersea Telecommunication Cables: Technology Overview and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, 13 September 2022.

6. Kate Duffy, “Satellite Internet Services Like Elon Musk’s Starlink Won’t Make Giant Undersea Cables Extinct, Experts Say,” Business Insider, 5 March 2022.

7. Rona Rita David, “Submarine Cables: Risks and Security Threats,” Energy Industry Review, 25 March 2022.

8. “Submarine Cable 101,” TeleGeography, 2023; and Douglas R. Burnett, “Submarine Cable Security and International Law,” International Law Studies 97, 2021. Breaks typically occur in known, high-traffic areas where multiple cables exist and near-immediate restoration is available through bandwidth sharing facilitated by mutual restoration agreements or ad hoc commercial arrangements as repairs proceed.

9. Yuan-Tao Weng, et al., “The ML 6.7 (MW 7.1) Taiwan Earthquake of December 26, 2006,” Learning from Earthquakes.

10. Alexander Downer, “The Threat to Britain’s Undersea Cables,” The Spectator, 29 October 2022; and Dan Swinhoe, “The Cable Ship Capacity Crunch,” Data Center Dynamics, 6 December 2022.

11. Gallagher, “Undersea Telecommunication Cables.”

12. Philip Oltermann, “State Actor Still Main Suspect behind Nord Stream Sabotage, Says Investigator,” The Guardian, 6 April 2023.

13. See Steve Weintz, “Forget Nuclear Weapons, Cutting Undersea Cables Could Decisively End a War,” The National Interest, 30 December 2019; “4.3 Kilometers of Subsea Cable Vanished Off North Norwegian Coast,” High North News, 10 November 2021; and Simon Sharwood, “Clumsy Ships, One Chinese, Sever Submarine Cables that Connect Taiwanese Islands,” The Register, 21 February 2023.

14. Downer, “The Threat to Britain’s Undersea Cables.”

15. Lane Burdette, “Leveraging Submarine Cables for Political Gain: U.S. Responses to Chinese Strategy,” Journal of Public & International Affairs (5 May 2021); and Stacia Lee, “International Reactions to U.S. Cybersecurity Policy: The BRICS Undersea Cable,” The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington, 8 January 2016.

16. Executive Office of the President, “Executive Order 13913: Establishing the Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector,” The Federal Register, 4 April 2020.

17. Joe Brock, “U.S. and China Wage War Beneath the Waves—Over Internet Cables,” Reuters, 24 March 2023.

18. “Submarine Cable Landing Licenses,” Federal Communications Commission.

19. Federal Communications Commission, Final Report—Interagency and Interjurisdictional Coordination, Communications Security, Reliability, and Interoperability Council, June 2016.

20. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency, National Infrastructure Protection Plan; Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency, “Sector Coordinating Councils”; and Gallagher, “Undersea Telecommunication Cables.”

21. CAPT Douglas R. Burnett, USN (Ret.), “Repairing Submarine Cables Is a Wartime Necessity,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 148, no. 10 (October 2022).

22. Gallagher, “Undersea Telecommunication Cables.”

23. Two of the Coast Guard’s founding services are the Revenue Cutter Service and the Lighthouse Service. Both were commissioned for the protection and support of maritime commerce, one by monitoring and maintaining physical commerce and the other through the upkeep of critical infrastructure.

24. U.S. Coast Guard, Maritime Commerce Strategic Outlook, October 2018.

25. U.S. Coast Guard, Cyber Strategic Outlook, August 2021.

26. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Global MOTR Coordination Center (GMCC).” The MOTR Plan is commonly used to orchestrate responses to migrant and drug interdictions, terrorism, and piracy. Adversary state-led strategic threats do not fall within the established or expected parameters of the GMCC or the MOTR Plan.

27. Richard Winton, “Coast Guard Targets Second Vessel Tied to Orange County Oil Spill,” Los Angeles Times, 19 November 2021; and Matt Burgess, “‘Dark Ships’ Emerge from the Shadows of the Nord Stream Mystery,” Wired, 11 November 2022.

28. The general international consensus that the Coast Guard’s presence is not inherently threatening permits greater flexibility for both peacetime and gray zone response.

29. Such other agencies may include the FCC, DoD, Maritime Administration, and Office of the Director of National Intelligence.