Manpower is sea power—and right now, the difficulty generating manpower severely limits the capacity to create sea power. Weak recruiting coupled with troubling long-run labor force trends make correcting this problem both challenging and necessary. Solutions and options exist, but enacting them starts with correctly assessing the present state of recruiting and the roots of the problems in the all-volunteer force (AVF).

The recruiting challenges confronting the Sea Services are not unique. The Army flat out missed its fiscal year (FY) 2022 targets, and the Air Force and Navy achieved their FY22 objectives largely by accelerating FY23 accessions. Only the Marine Corps cleared its goals.1 Unfortunately, short-run successes may simply accelerate a demographic reckoning.

Traditionally, the services all target the same cohort: high school graduates between ages 18 and 24. This is a shrinking pool. According to figures from the National Center for Education Statistics, the number of new public high school graduates is expected to crest by FY25 at approximately 3.8 million and then start declining to around 3.5 million by FY31.2 Consequently, while the current recruiting environment is difficult, the future looks to be worse. The question is whether the all-volunteer force can cope with this level of stress in a manner that allows the nation to achieve its policy goals at sea, particularly the Navy’s desire and need to recapitalize the fleet.

Money Is Not The Problem . . .

Five decades on, it is easy to forget why the AVF was created. The draft did not end because it was unfair. It ended because it was economically inefficient. During the 1960s, a slew of economists argued against the draft, generally to little effect, on the ground that it was inequitable. It was the work of Walter Oi that turned the argument in favor of an AVF.3 Oi argued the AVF would reduce three potential costs: from personnel turnover as draftees enter/exit the force, from coercing a subset of draftees to serve against their will, and from potentially underpaying those who would have volunteered under any circumstances.4 Overall, Oi argued, the transition from drafting unwilling conscripts to an all-volunteer force would increase budgetary costs in the short run (as a way to induce citizens to serve) but ultimately would reduce social costs, thereby creating a more stable, cost-effective, and productive military.

The economic foundation of the AVF hinged on encouraging recruits to choose military service as an alternative to civilian employment. And there is a salient subtext within Oi’s argument: For the AVF to work, potential recruits must perceive military service as being at least as remunerative as civilian employment options. Recruits who view military service as less attractive than competing civilian employment either will choose to work somewhere else or will require greater monetary incentives to serve.

Consequently, Oi anticipated military compensation costs would rise in the short run, but he expected the military and civilian sectors of the labor market ultimately would achieve equilibrium. This does not mean they would have equal wages. To the contrary, given the “risk premium” (i.e., the recognition that military service is fundamentally more dangerous than most civilian employment), military wages and salaries must be higher to compensate. Rather, the sign of equilibrium between the two labor markets would be a stable risk premium and differential in pay. The questions then become whether the civilian/military wage gap is stable, and whether Department of Defense (DoD) compensation targets are being met.

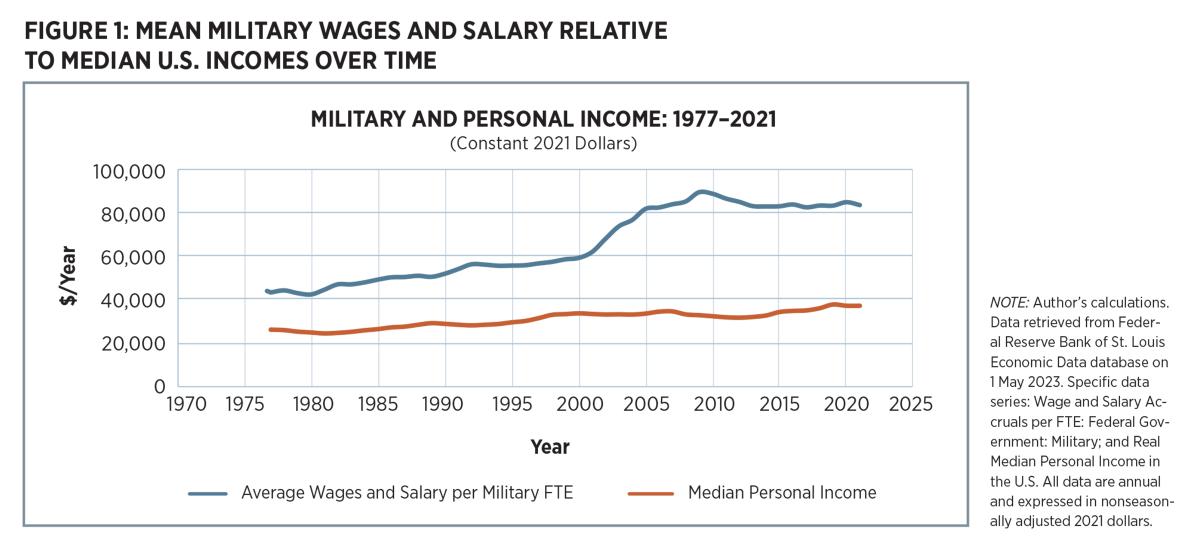

Figure 1 compares mean military wages and salaries against median personal income in the United States between 1977 and 2021. Over this period, mean military compensation was above median civilian income, and, on average, military personnel were in the upper half of U.S. income distributions.5 Generally, in the early stages of the AVF, DoD policy goals with respect to income percentiles were met, and from 1977 until about 2002, the gap between mean military compensation and median civilian personal income was fairly constant.

Unfortunately, since 2002–3 the gap between civilian and military compensation has ballooned. Some of this is a byproduct of stress on the force. The increase in relative compensation since 2003 was concurrent with and symptomatic of challenges in military recruiting, particularly for the Army, during the FY2005–7 period.6

Institutionally, the military dealt with part of this issue by adjusting quality standards for recruits, but it also threw money at it. So, while DoD policy since 2002 has been to target military compensation at the 70th percentile of incomes relative to civilian compensation (adjusting for age and education), in practice, compensation (the sum of salary and benefits) now exceeds the 90th percentile for enlisted personnel and approaches the 80th percentile for officers.7

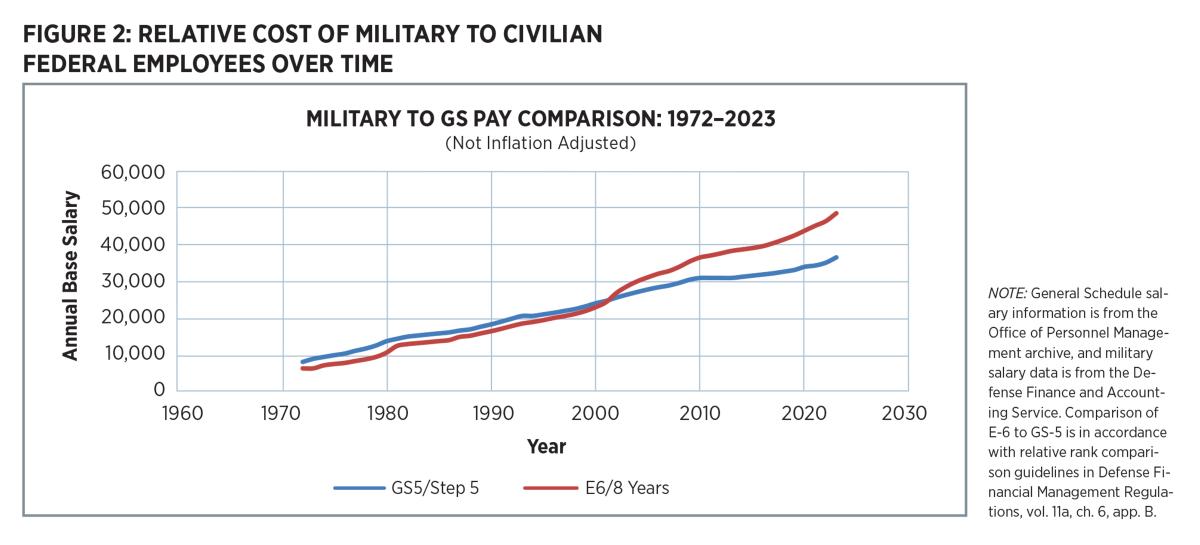

For context, compare relative wage growth of military and civilian incomes in the U.S. government. In 1977, the base salary of a GS-5 was 25 percent higher than the base salary of an E-6, but by 2017, the relationship had reversed, and the uniformed service member was 25 percent more expensive in base salary than a civilian federal employee. Indeed, as can be seen in Figure 2, civilian personnel have been markedly cheaper than uniformed personnel essentially since the beginning of the war on terrorism era.8 When compared with both general civilian incomes and GS incomes, military pay clearly stacks up well. Failure to compete with civilian salaries does not appear to explain current recruiting shortages. Money is not the problem.

. . . Costs Are

Costs, however, are a serious problem. Between 2000 and 2014, while total defense budget authority rose by 33 percent, military personnel costs increased by 46 percent, and real (inflation-adjusted) base pay for active-duty personnel rose by 19 percent. Even with the effects of the 2011 sequestration, the higher rates of increase for personnel costs relative to overall budgets meant that military personnel costs approached one-third of the defense budget by FY18.9 And while the rate of increase declined over the past five years, personnel compensation still accounts for more than 25 percent of the defense budget.10

So, the Navy is not achieving recruiting goals despite devoting ever-increasing resources to military compensation. Worse, the Navy’s FY23 shipbuilding plan assumes increases in appropriations from 23 to 35 percent relative to the last five years—despite Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal budget deficit will double by FY33 and the national debt will increase to 119 percent of GDP, the highest on record, over the same time period.11

Something has to give. Spending on personnel is already markedly above target levels but still failing to achieve goals, while the Navy is committing itself to increasing shipbuilding faster than national income growth. In the present budget environment, the two are not compatible. Left unchecked, spending on personnel threatens virtually all other defense-related spending, most notably the Navy’s recapitalization and expansion efforts. Supporting both higher personnel costs and a larger fleet is feasible only if defense expenditures increase from roughly 2 percent of GDP/year to 4-6 percent—rates not seen since the height of the Cold War—and even then only by further ballooning the deficit, raising taxes, or dramatically reducing other areas of the U.S. budget (e.g., Social Security, Medicare, etc.). None of those are attractive options.

The time has come to seriously reexamine military manning, pay, and compensation. Fifty years ago, the United States adopted the all-volunteer force because it could not afford the draft. The Navy can no longer afford the AVF, either.

A Way Out

The all-volunteer force is at a crossroad. Born of economic necessity, it now fails to provide sufficient manpower and is rapidly becoming a budget buster conflicting with fleet recapitalization goals.

Options exist. There are paths to expanding the Navy’s labor pool and increasing deployable capacity while reducing personnel costs. The key is reducing the demands placed on the AVF. There are three primary approaches to achieving this end: substitute to civil service, expand recruitment of women, and leverage the reserve component.

Substitute Civil Service. Not all military jobs require uniformed personnel. Conducting a zero-baseline review of existing positions, particularly in nondeploying shore-based commands and combat support agencies, to identify where civil service employees can effectively replace military personnel improves both manning and costs. To start, civilianizing positions opens the workforce to the entire labor force, not just the military’s preferred 18–24 year old cohort. This, in turn, frees uniformed personnel to perform functions that can be done only by service members. Last, given that civil service employees are generally cheaper than military personnel in both salary and total compensation, civilianizing can reduce costs for the entire Navy.12

Expand Recruitment of Women. Relative to male students, women increasingly graduate high school at a higher rate, attend postsecondary education at a higher rate, and complete postsecondary education at a higher rate.13 Consequently, women represent a pool of high-quality recruits who are also historically underrepresented within the Navy. Indeed, across all services, only 17.3 percent of active-duty and 21.4 percent of reserve component personnel were women in 2021.14 At the same time, labor force participation rates for women over age 20 have consistently stayed well over 55 percent for the past decade. Closing the gap between the rate at which women serve in the military and the overall female labor force participation rate would significantly improve the Navy’s personnel levels.

Leverage the Reserve Component. Although the Navy Reserve faces its own recruiting challenges, expanding at-sea support from the Reserve offers a potential solution to active component shortfalls. The Navy Reserve and specifically the Selective Reserve represent a ready pool of nearly 50,000 trained sailors prepared for sea. More critically, they are a “pay as used” resource.

In earlier generations, the Navy Reserve had ships.15 It should again. Returning to the Cold War–era model of assigning a certain fraction of the fleet specifically to reservists, and then using them operationally when and as needed, simultaneously addresses the Navy’s larger manning issues while potentially reducing personnel costs. Ideally, new-construction Constellation-class frigates could be assigned to the Navy Reserve with Training and Administration of the Reserve (TAR) skeleton crews readying the ship for at-sea periods with embarked Selective Reserve crews. Absent that, obtaining additional expeditionary fast transports, next-generation logistics ships, or landing ships medium crewed by reservists trained in distributed logistics operations would increase the Navy’s capacity to support expeditionary advanced base operations without imposing additional demands on the active component fleet.

Sound Collision and Brace for Shock

The Navy needs a rudder check on its manpower challenges. In the face of declining labor pools, the limits of the AVF and pay incentives are becoming transparent. The intersection of these limits and the Navy’s real need to expand shipbuilding budgets presents the Navy with a complicated challenge: how to increase at-sea capacity while reducing costs. Widening the Navy’s labor supply through increased use of civilians, expanded recruiting of women, and greater use of reservists offers options. The challenge now is to do it fast enough to make a difference.

1. Katherine Kuzminski and Thomas Spoehr, “Bad Idea: Relying on the Same Solutions to Meet the Military Recruitment Challenge,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 10 March 2023.

2. Department of Education, “High School Graduates, by Sex and Control of School; Public High School Averaged Freshman Graduation Rate (AFGR); and Total Graduates as a Ratio of 17-year-old Population: Selected Years, 1869–70 through 2030–31,” November 2021.

3. Beth J. Asch, James C. Miller III, and John T. Warner, “Economics and the All-Volunteer Force,” In Better Living through Economics, ed. John J. Siegfried (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 253–68.

4. Walter Oi, “The Economic Cost of the Draft,” American Economic Review 57, no. 2 (May 1967): 55–58.

5. Care should be taken in comparing these figures, for military compensation is on a per full-time equivalent basis while personal income is on a per-capita basis. However, the main point is to compare the relative growth rates over time, so the salient point is their comparative slopes.

6. Lawrence Kapp, Recruiting and Retention: An Overview of FY2011 and FY2012 Results for Active and Reserve Component Enlisted Personnel (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2013).

7. Congressional Budget Office, Approaches to Changing Military Compensation (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, 2020).

8. This comparison understates the cost differential between uniformed and civilian personnel because it simply compares base salaries. Including allowances, etc., offered to uniformed personnel will increase the potential savings of shifting to civil service.

9. Department of Defense, Providing for the Common Defense: A Promise Kept to the American Taxpayer (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, September 2018).

10. David Mosher, “Trends in DoD’s and VA’s Budgets for Military Compensation,” presentation at the Military Manpower Roundtable, Washington, DC, 22 March 2023.

11. Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2023 Shipbuilding Plan (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, 10 November 2022); and An Update to the Budget Outlook: 2023–2033 (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, 2023).

12. Congressional Budget Office, Replacing Military Personnel in Support Positions with Civilian Employees (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, 2015).

13. William J. Hussar and Tabitha M. Bailey, Projection of Education Statistics to 2028, 47th ed. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education: National Center for Education Statistics, 2020).

14. Department of Defense, “Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report—Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues,” 14 December 2022.

15. During college, the author’s father served on board the USS Charles E. Brannon (DE-446) as a Navy reservist, eventually selecting for commissioning through the Reserve Officer Candidate program.