The main tenets of deterrence in the western Pacific are the persistent forward presence and prudent use of capable U.S. and allied forces in and around the first island chain, and success is indistinguishable from the status quo. According to U.S. military and government analysts, compared with this effort to maintain the balance of power, China has a more straightforward task in attempting to disrupt it. They contend that once China gains the ability to execute a successful invasion of Taiwan, its tactical and timing advantage over U.S. and allied forces will only grow, owing in no small part to the necessity of daily deterrence with the U.S. Navy’s thinly stretched forces matched against the massed People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN).1

This is a false assumption. Any strategy for deterring Chinese aggression in the western Pacific should recognize that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is strategically cornered and, after ceding every other aspect of the strategic battlespace to the United States and allied nations, is now grasping for control of the narrative.

If the United States does not challenge the Chinese narrative of inevitable unification with Taiwan, it risks neutering its own deterrence posture. Planners and policy makers must start mapping out how the United States will confound, interrupt, and, if necessary, defeat China. This includes a new role for military public affairs, a willingness to move toward permanent U.S. basing on Taiwan, and a national “moon shot” on uncrewed aerial systems (UASs) as a means of countering any possible invasion.

China’s Weaknesses

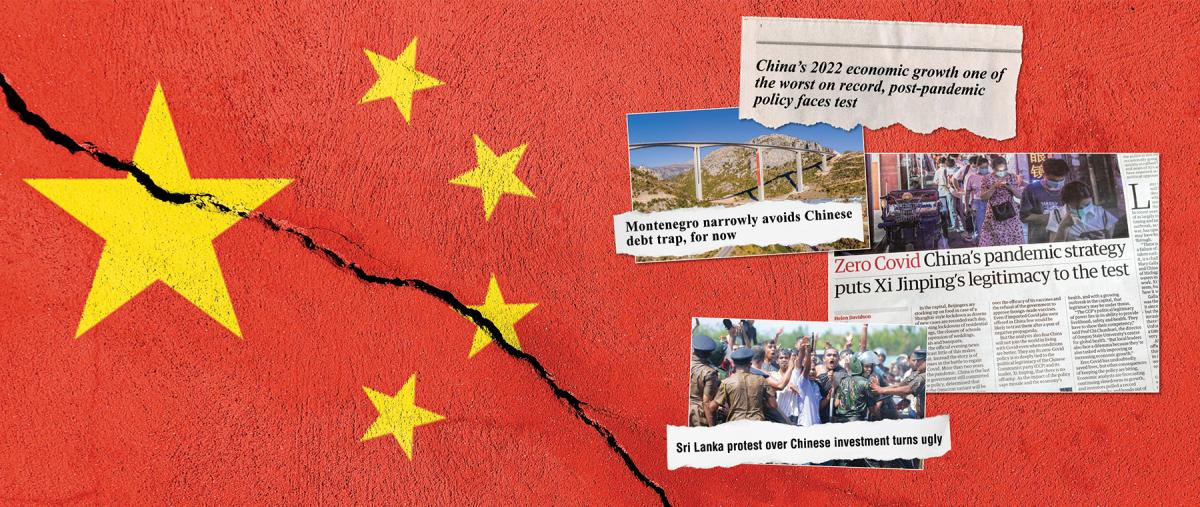

To begin, a look at China’s inherent weaknesses is required. Economics is the primary lens through which to analyze these weaknesses, because the CCP’s legitimacy, its ability to mass military power across its near abroad, and its ability to project soft power around the world all depend on the party’s ability to guarantee blockbuster topline economic growth at home.2 This promise is about to be broken, as 2022 recorded the slowest growth in China in decades (excluding the pandemic hit in 2020).3

The CCP will claim its policy choices, such as the zero-COVID restrictions and the “common prosperity” crackdowns on business, were for the common good.4 But that narrative conceals a more serious and less solvable issue: China may be primed for economic collapse.

The country currently is experiencing mass retirement of its senior citizens, and China’s youth population is both too small and too unwilling to make up the consumption shortfall. Demographics played an outsized role in China’s rise at the end of the last century, as a disproportionately large cohort of Chinese entered their prime years of consumption and economic productivity (and were limited to one child) just as Chairman Deng Xiaoping liberalized the Chinese economy—powering double-digit growth for the subsequent four decades.5 This generation is now retiring, and as a dearth of state elder care forces both retiring parents to depend on a single working child, China is entering a contraction in demand on a speed and scale not seen since 1989 in Japan, when that country transformed virtually overnight from an ascendant would-be superpower to an economically stagnant nation of elderly savers. The impact of a post-growth China on the global economy will be just as profound as the 40 years of China-based growth that preceded it.

The United States therefore needs a strategy that recognizes China, not as an ascendant superpower to be contained, but as a fragile yet dangerous confederation in decline to be managed. This should not be met with jingoistic relief by the U.S. national security apparatus or the U.S. public. As Russia has demonstrated in Ukraine, fragile confederations in decline can be more dangerous than ascendant powers, especially when the former believes they are the latter.

Public Relations Wars

China views public relations as an asymmetric weapon it can use to put other nations’ governments into conflict with their respective militaries. Its strategy is to have the Ministry of Foreign Affairs extend a generous economic carrot of trade agreements and infrastructure pledges, while the PLA wields an ever-present, ever-more-capable military stick. In addition, China has established itself as the indispensable economic heavyweight in terms of its ability to rapidly and efficiently fund infrastructure and development projects around the world, seemingly with few strings attached. Nations and their respective populations are told they can share in the economic growth that restored China to the geopolitical center stage, and the only ask is that they respect China’s “sovereignty,” meaning its claims over Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet, Xinjiang, and large swaths of the South China Sea. Compared with the economic benefits, the geopolitical price appears low and even irrelevant in a globalized world, forcing these nations’ militaries into ideological conflict with their more economically motivated and diplomatically dovish governments.

The United States must not allow its government and military to be divided along these lines. Crafting a military public relations strategy that recognizes China as a belligerent is essential to ensure the U.S. geopolitical posture is ironclad and unified. This strategy need not echo the brash tone of the “wolf warrior” diplomats in Beijing’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but it must be public, proactive, and prominent to ensure U.S.-China relations remain stable.

Public: The strategy must publicize that China is a poor investment partner. When demographics put the Chinese economy into a downward spiral that exceeds the CCP’s ability to believably revise figures upward, China likely will siphon off or entirely withdraw foreign aid commitments in an attempt to make up the shortfall. The ongoing economic crisis in Sri Lanka, often used as an example of China’s “debt trap diplomacy,” is a stark example of what happens when a country addicted to Chinese foreign aid is suddenly confronted with its absence.

Proactive: It must seize the narrative on China’s foreign aid commitments—namely, the numerous projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—and reveal them as reactive decisions rather than sound foreign policy.

The U.S. Navy and its allies have the capability to disrupt or even sever China’s oil and gas supply. A lack of overland pipeline infrastructure and several critical maritime choke points are geopolitical vulnerabilities China cannot command its way out of, no matter how quickly it transitions to electric vehicles. Therefore, in 2013 President Xi Jinping launched the BRI as the most expensive public relations campaign in history, with the goal of convincing the world that China is sharing its wealth to forge economic alliances and promote “win-win cooperation.”

It is a ruse. The BRI is a buckshot volley of cash that represents Xi’s admission that, in the event of a conflict between China and the United States, he cannot guarantee his country’s energy security. Western media narratives thus far mainly have focused on China outcompeting the United States in a new “scramble for Africa,” seeming to suggest that the United States ought to match Chinese foreign investment pound for pound and that the inability to do so is a weakness. This narrative is misguided and imperialist, and it is encouraged by the Chinese propaganda machine. The unfortunate truth is that many of the countries in which China invests are poorly governed and plagued by corruption, making it uncertain that any money invested would go to the right place or see a positive return. China cares little about either of these things, as its main goals are gaining a foothold in these countries and achieving a narrative victory over the United States.

Taking back the narrative means emphasizing how desperate, irresponsible, and, most important, reactive the BRI projects truly are.

Prominent: The U.S. military public relations strategy must occupy a prominent place in the national security posture. Public relations ought to precede military initiatives and operations to get the United States off its heels and in a position to shape the global conversation. Moving the Department of Defense press briefing to the White House and holding it directly before or after the White House press secretary’s briefing would communicate a strong message of unity between Pennsylvania Avenue and the Pentagon and would give military operations much-needed press and public recognition.

This purposefully departs from the military tradition of speaking softly and carrying a big stick, because China views silence as indecision and restraint as permission, especially with regard to the Taiwan Strait. War will be avoided by giving China a clear signal that there are no avenues for further geopolitical provocation that do not lead to direct conflict with the United States, and the clearest signal would be to establish a U.S. military base on Taiwan.

Defense of Taiwan

Restoring permanent U.S. basing on Taiwan is by far the most provocative part of this new strategy. It would be a departure from decades of U.S. foreign policy and, as a unilateral action, would draw a range of reactions from the international community, from silent support to open condemnation. It would not, however, bring the world closer to war. If done rapidly, it could be the strongest and most enduring example of deterrence in the history of U.S.-Chinese relations.

At present, the President’s decision on whether to come to Taiwan’s defense in the event of an invasion is a political decision, which encourages Beijing to test Washington’s resolve. The United States attempts to walk the tightrope between maintaining the necessary economic relationship with China and signaling severe consequences for further transgressions. Strategic ambiguity is a sound policy in relations with a country that is economically essential or militarily near parity, but it is an unwise policy for China, the only country that is both.

If instead of hoping China receives the correct message from an ambiguous policy, the United States were to permanently station several thousand American troops at the military base in Taoyuan, Beijing’s risk calculus would change. An attack on Taiwan would be a Pearl Harbor event, committing the United States to the conflict and all but ensuring incalculable losses for both sides. The fact that this is such an undesirable outcome for all parties is the point: A deterrence posture must carry the threat of consequences so unthinkable that it deters aggression. China will be unfazed by anything less.

A reestablished U.S. presence at Taoyuan would be more than a geopolitical dead man’s switch. The base also would be ideal as a launching station for a ramped up UAS fleet. China’s heavy investments in missile technology have produced the game-changing DF-26, which threatens every detectable U.S. asset in the region.6 In the initial days and weeks of a potential Taiwan invasion, the main U.S. naval response likely would come from the submarine force, which would take significant time to arrive on station with limited armament, would be severely challenged by the Taiwan Strait’s shallow water, and would be persistently threatened by air-dropped torpedoes from patrolling PLAN aircraft. By the time U.S. submarines could begin to significantly attrite the invasion force, Taiwan might already have been pummeled into submission.

A more immediate response is needed. The U.S. UAS fleet must be expanded significantly and stationed in and around Taiwan to rapidly respond to a potential invasion. Multiple launch points should be established in the vicinity of Taiwan, including at sites in Japan, the Philippines, Australia, and Guam, further complicating China’s risk calculus in taking out the UAS fleet in an initial strike.

NATO’s support of Ukraine has set a precedent for countries to supply UASs to aid in a conflict; such contributions are more politically palatable and theoretically less escalatory than supplying troops, though thus far they have proved to be at least as effective.7 The United States must recognize this as the most likely and easiest way to muster support for the defense of Taiwan from countries that otherwise would be unwilling to intervene. Together with allies and partners, the United States could assemble a massive UAS fleet around the periphery of the South China Sea to counter a would-be invasion force. Signal jamming by China would be a threat, but a platform attempting to jam the UASs also could disrupt its own communications systems and possibly reveal its location for manned aircraft to execute follow-on strikes.8

Deterrence Is Imperative

U.S. experience in conflict with China goes back seven decades to the Korean Peninsula, when an economically battered, militarily outmatched, and nonnuclear China fought to a draw with the United States, which was buttressed by 21 allies and at the peak of its global economic and geopolitical influence. Circumstances have changed, and not in America’s favor. Preventing conflict in this decade means outthinking China by understanding its motives, goals, and weaknesses, as well as expanding America’s strategic breadth beyond the bounds of last century’s policy motivations. The Taiwan Relations Act requires that “determination of Taiwan’s defense needs shall include review by United States military authorities in connection with recommendations to the President and the Congress.”9 An honest review would conclude that Taiwan’s defense needs in this moment are the posture, presence, and deterrence that only Washington can provide. Conflict must be deterred, and positive action must be taken to ensure it is, for the survival of Taiwan and peace for this and future generations.

1. Kathrin Hille and Demetri Sevastopulo, “Taiwan: Preparing for a Potential Chinese Invasion,” Financial Times, 7 June 2022.

2. John Culver, “How We Would Know When China Is Preparing to Invade Taiwan,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 3 October 2022.

3. Kevin Yao and Ellen Zhang, “China’s 2022 Economic Growth One of the Worst on Record, Post-pandemic Policy Faces Test,” Reuters, 17 January 2023.

4. Ryan Haas, “Assessing China’s ‘Common Prosperity’ Campaign,” Brookings, 9 September 2021.

5. Briana Boland, Jude Blanchette, Kevin Dong, and Ryan Hass, “How China’s Human Capital Impacts Its National Competitiveness,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 16 May 2022.

6. CSIS Missile Defense Project, “DF-26,” Missilethreat.csis.org, 6 August 2021.

7. Andrew Chuter, “New British Aid Package for Ukraine Includes Micro-drones,” Defense News, 24 August 2022.

8. Government Accountability Office, “Science & Tech Spotlight: Counter-Drone Technologies,” March 2022.

9. “H.R. 2479, Taiwan Relations Act, 96th Congress” (1979–1980), Congress.gov.