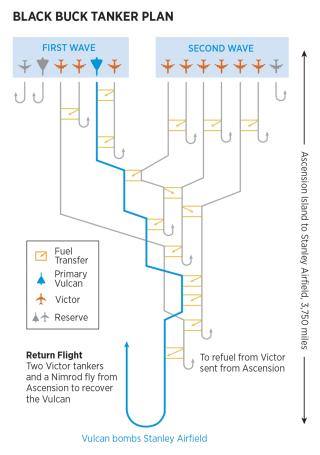

In the dark April skies high above the Atlantic, the three aircraft were already several hours into their mission. Code named Black Buck, the deep strike package of three British planes originally contained 13 aircraft: 11 Victor aerial refueling tankers and 2 Vulcan bombers, with the second as a reserve.1 The lead Vulcan turned back because of mechanical issues shortly after takeoff, leaving the reserve to fulfill the mission. One by one, the tankers refueled each other and the single bomber. Those that gave their fuel away turned back toward Ascension Island. The Vulcan pilot remarked, “We’re short on fuel, but we’ve come this far, I’m not turning back now.”2 Now alone, the Vulcan proceeded to its target: the runway at Port Stanley on Falkland Island. Achieving surprise, the Vulcan released its bomb load. Explosions rocked the airfield, and the lone Vulcan made the long trek back to Ascension Island.

Superficially, the 1982 British mission during the Falklands War has little to do with naval aviation. However, the Navy’s recent successful testing of the MQ-25 Stingray aerial refueling drone on board an aircraft carrier places naval aviation at the precipice of a paradigm shift. Unmanned carrier tankers such as the Stingray can embed with strike packages, extending the range of crewed strike fighters farther than current airwing tankers can. By accompanying the strike packages to the edge of or into contested airspace, the Navy is reintroducing the deep strike capability—one only resident within the Air Force in recent decades.

The Range Problem

The Black Buck raid demonstrated the strategic necessity for deep strike. With the British carrier fleet still weeks away from being able to provide a response to the invasion of the Falklands, the British required immediate action to demonstrate resolve. The closest available base was Ascension Island, nearly 3,400 nautical miles (nm) away. The Vulcan bombers did not possess the organic range for a round trip, necessitating robust aerial refueling support. To this end, the Black Buck raid employed nearly every available tanker in the British inventory.

The continued maturation and proliferation of capable antiaccess/area-denial (A2AD) systems and strategies may require high-value units such as aircraft carriers and dedicated traditional aerial refueling platforms to maintain an ever-increasing standoff distance. To make matters worse, the Navy and Air Force’s most recent strike-fighter acquisitions do not possess sufficient combat range without the assistance of tankers.

The current construct for distant aerial refueling consists of Air Force or Marine Corps aerial tankers dragging a strike package to a point or orbiting within uncontested or permissive airspace. If these large tankers are unavailable, carrier strike groups cannibalize strike-fighters for use in a support tanking role, referred to as buddy tanking.

F/A-18 Super Hornet aircraft configured as tankers provide organic carrier tanking operations. However, this also results in less combat capability, since tanker-configured F/A-18s cannot participate as strikers or fighters. Aside from the reduced offensive punch, there are other detractors that make buddy tanking a less than ideal solution. First, buddy tanker pilots are typically more senior, depriving strike packages of experienced aviators. Super Hornets also are less fuel efficient when configured as tankers because of parasitic drag penalties, further exacerbating the issue. The result is a neutered strike-fighter force lacking the range to project power without tanker support, and individual tankers lacking the endurance and range to accompany the strike package to contested areas at distances demanded by carrier standoff from A2/AD systems. The range problem also extends to fifth-generation fighters such as the F-35 Lightning II. The F-35C offers a superior range when compared with a fighter- or strike configured-F/A-18, but it is only an incremental improvement and still relies on tankers to reach tactically relevant ranges.

Shifting Paradigms

Lost combat power is not an issue with the Stingray, which promises to shift the current aerial refueling paradigm to small organic distributed tankers operating closer to and possibly even in contested environments.

In addition, since Stingrays are unmanned systems, they do not deprive air wings of pilots and striking power. Fully autonomous and sporting low observable features, the Stingray can transport fuel farther and more efficiently. The Stingray’s 500-nm range represents a generational leap in capability when compared with the current carrier air wing refueling construct, while providing at least 15,000 pounds of fuel for air-to-air refueling.3

Beyond tanking, the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments argues that the Stingray could be outfitted to fulfill the intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISR&T) roles, augmenting the future carrier air wing’s intelligence and attack networks.4 A future Stingray orbiting near or in contested airspace could assist strike packages by feeding battlespace awareness networks, acting as a communication relay with the fleet, and delivering fuel for the strike-fighter package’s return journey if required.

The Need for On-Demand Give

The Stingray promises on-demand air-to-air refueling, allowing strike-fighters to refuel as necessary. Thus, carrier-based aircraft can extend their combat range beyond the advertised distances and absolute limits. After the successful U.S. amphibious landings on Guadalcanal during World War II, Japan launched an immediate air counteroffensive. Rabaul, the nearest Japanese-controlled airbase from the landings, was more than a 1,200-nm roundtrip. Japanese fighter pilots stretched their ranges to the “absolute limits” and lacked the necessary fuel to fight and defend effectively once over the target areas.5 Many Japanese pilots and aircraft survived the initial battle but were unable to make the long trek home because of battle damage.6

More than 20 years later, during the Vietnam War, North Vietnamese antiaircraft fire struck two Air Force F-4C Phantoms piloted by Captains Bob Pardo and Earl Aman.7 Captain Aman’s Phantom received a critical blow to its fuel tank and quickly lost most of its fuel, while Pardo’s aircraft’s fuel leaks were less severe. With the nearest tanker out of reach over Laos, Captain Aman’s Phantom flamed out over enemy territory. In a maneuver now dubbed “Pardo’s Push,” Pardo maneuvered his Phantom and used the tailhook of Aman’s Phantom to push the flamed-out and gliding Phantom out of hostile territory.8 Once over Laos and after traveling 88 miles, Pardo’s Phantom also flamed out and both aircrews safely ejected outside enemy territory.

If a tanker had been closer, the two F-4s might have been saved. The aircrew of an Air Force KC-135 aerial tanker saved an F-16 kept its pilot from having to eject in 2015 when the aircraft suffered a catastrophic fuel malfunction over Islamic State territory. With the F-16 unable to use more than 80 percent of its internal fuel, the KC-135 escorted the F-16 back to base by refueling it every 15 minutes, allowing both aircraft and crew to return safely.9 Distributed unmanned tankers could accompany strike packages for long-range strikes, reducing fuel-emergency risks. Because Stingrays are unmanned and possess low-observable features, they can be dispatched to meet returning strike packages in fuel extremis to ensure returning aircraft can recover safely.

Mass to Survive

Quantity is a quality of its own, and the mass of a strike package has implications for redundancy in capabilities and protection. Proper force packaging ensures the effectiveness and survivability of a strike-fighter package.10 The correct ratio of weapons to targets and protection measures ensures the package will achieve the desired effects while sufficiently degrading enemy countertargeting kill chains. Beyond protection measures, massing aircraft provides redundant capabilities. As demonstrated in the Black Buck raid, redundancy is important.

In addition, massing unmanned aircraft with manned strike packages complicates enemy targeting by creating a target-rich environment, increasing the probability of survival of any single aircraft. Stingrays with ISR&T payloads accompanying a strike package could bolster mass without adding more manned platforms. This would allow future air wing commanders to lower the individual risk to manned aircraft while potentially having the latitude to increase overall mission risk to improve the odds of success.

If It Works, Why Fix It?

The inclusion of the KC-46 Pegasus in the Air Force tanker fleet and the expansion from three to four Marine aerial refueler transport (VMGR) squadrons operating the venerable KC-130 Hercules portend that the Department of Defense has embraced large, centralized tanking operations in permissive and uncontested environments. While this may have worked for the past two decades, the proliferation and maturation of A2/AD systems indicates that future operating environments will be contested. Centralized tankers offer efficiencies in volume at the expense of capability and flexibility. On-demand tankers such as the Stingray promise a distributed alternative where the loss of any individual tanker would hardly affect the emerging distributed aerial refueling concept.

Beyond this, the Air Force is facing a looming tanker shortage. Retired Army General Stephen R. Lyons, the former commander of U.S. Transportation Command, stated that KC-135 Stratotankers and KC-10 Extenders are the “most stressed in the mobility enterprise” and “most relevant to any crisis or surge.”11 The KC-46, which will bridge the tanker gap, has been plagued with issues since its inception. The most recent issues stemmed from concerns over the KC-46’s maneuvering characteristic augmentation system after the infamous 737 MAX crash in 2019 followed by the discovery of “excessive” fuel leaks in 2019.12 To make matters worse, the Air Force is pushing ahead with its planned retirements of KC-135 and KC-10 airframes.13

On 18 September 2021, Lockheed Martin unveiled its next generation “low-risk” tanker platform named the LMXT, based on the Airbus A330, as a direct competitor to the KC-46, which was developed out of Boeing’s 767.14 While the LMXT tanker represents a generational leap over legacy platforms enabled by automated refueling, like the KC-135, KC-46, and KC-10 tankers, it is still a large centralized aerial refueler designed to operate in permissive environments. It will become high-demand, low-density asset that the military cannot afford to lose during peacetime—let alone in a war.

Critics of the Stingray will rightly note that refueling, even with stealthy tankers, would be an intrinsically vulnerable flight regime. However, measures can be taken that would mask tanker operations or decrease detection ranges. Manned and unmanned aircraft can rendezvous at lower altitudes below radar horizons during tanker operations, albeit with reduced fuel efficiencies. In addition, organic long-range tanking from the carrier will further open the aperture of available options without relying on the Air Force or Marine Corps.

Looking Forward

To project power, the Navy needs to increase the range of its striking force. Autonomous tanker aircraft capable of escorting strike packages closer to targets will help shift the balance back into U.S. favor. With the F/A-18 Super Hornet forecast to serve into the 2030s and the F-35 offering only an incremental range improvement, the Navy requires an interim solution to keep current strike-fighters relevant until longer-range strike-fighters are integrated into carrier air wings. The soonest this may occur is in the 2030s when the Next Generation Air Dominance systems are planned to be introduced into the fleet.

The future battlefield demands a reexamination of the current air wing construct. To keep the current airwing relevant, near-future strike-fighter packages may look remarkably like the Black Buck raid. All aircraft will originate from a single location—an aircraft carrier—with other airfields either too far, unavailable, or contested. Unlike Black Buck, these tanker aircraft will have the ability to follow the strike-fighters into contested airspace and could even provide other forms of combat support. In the future, no aircrew deep inside contested airspace should have to say, “We’re short on fuel, but we’ve come this far, I’m not turning back now.”15

1. Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: Revised and Updated Edition, vol. 2 (London, UK: Routledge, 2007), 283–85.

2. Dean Smith, “The Longest Bombing Run in History—Operation Black Buck in the 1982 Falklands War,” History Is Now, 16 October 2018.

3. Bryan Clark, Adam Lemon, Peter Haynes, Kyle Libby, and Gillian Evans, “Regaining the High Ground at Sea: Transforming the U.S. Navy’s Carrier Air Wing for Great Power Competition,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2018, vii.

4. Clark et al., “Regaining the High Ground at Sea,” vii, 68.

5. Maj Timothy L. Cubb, USMC, “CACTUS Air Power at Guadalcanal,” PhD dissertation, Southeast Missouri State University (1982), 25.

6. Cubb, “CACTUS Air Power,” 103.

7. Preston Lerner, “Bob Pardo Once Pushed a Crippled F-4 Home with His F-4. In Flight,” Air & Space Magazine, April 2017.

8. Lerner, “Bob Pardo.”

9. SrA David Bernal Del Agua, USAF, “KC-135 Crew Saves F-16 Pilot from Ejecting Over Enemy Lines,” U.S. Air Force News, 19 February 2016.

10. Clark et al., “Regaining the High Ground At Sea,” 59.

11. Brian W. Everstine, “TRANSCOM: Keeping KC-135s, KC-10s Will Avoid Capacity ‘Train Wreck,’” Air Force Magazine, 7 October 2020.

12. John A. Tirpak and Brian W. Everstine, “USAF Reviewing Training After MAX 8 Crashes; KC-46 Uses Similar MCAS,” Air Force Magazine, 22 March 2019; and Theresa Hitchenson, “Leaking KC-46 Fuel Lines Are Latest Serious Boeing Tanker Fault,” Breaking Defense, 31 March 2020.

13. Jan Tegler, “Air Force Seeks to Bridge Aerial Refueling Gap,” Air Force News, 14 March 2022.

14. Lockheed Martin, “LMXT: America’s Next Strategic Tanker,” 2022.

15. Smith, “The Longest Bombing Run in History.”