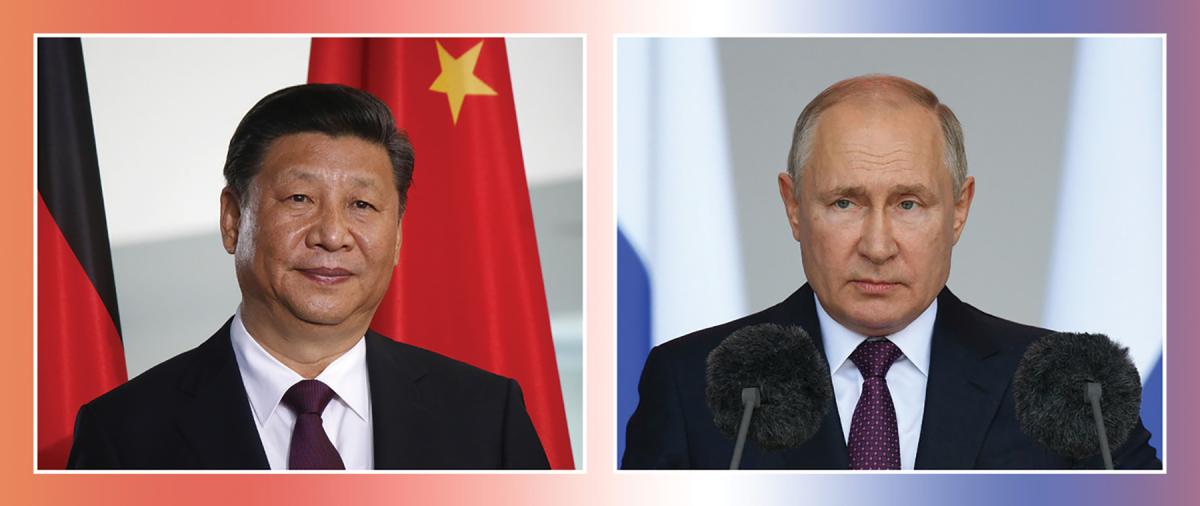

In Europe, a once-defeated nation reasserts itself. A strongman leader comes into power, rebuilding the nation’s economy, military, and cultural pride and incorporating ethnocentric rhetoric as part of the nation’s victim narrative. Under the guise of humanitarian intervention to protect ethnically homogenous “citizens” against “oppression,” the nation conducts cross-border military incursions into regions that ethnically and historically were part of it.

Nazi Germany—or modern day Russia?

In Asia, an ancient civilization rapidly industrialized over a few decades and is asserting itself as the central Asian military and economic power. With a dangerous combination of fervent nationalism and the need for resources to fuel its economic growth, it expands its interests beyond its borders, coming into contention with established European influence in the region.

Imperial Japan—or Communist China?

Is it 1937 or 2022?

. . . And 1937 was two years from the start of World War II.

This is an example of great power competition training that should be provided to all shipboard personnel, regardless of rate and rank.

Judging by the 2018 National Defense Strategy and global destabilization, we are not a peacetime Navy, we are a prewar Navy.1 Despite this, Navy leaders have not consistently prioritized effective training and education at the deckplates level. This must change. All technology, weapons, ships, and aircraft in development to counter Russia and China have a universal commonality—sailors. If the Navy does not consistently educate sailors on the potential threats, it is not preparing the man-in-the-loop for the combat systems needed to win—or hopefully deter—a potential conflict.

Deckplates-Level Education

During the war on terrorism, military leaders could show the “why” with a photo of the Twin Towers on 11 September. Great power competition is the new “why,” but there are few concrete examples, and the average chief or junior officer is not educated on the relevance and ramifications of these complex international geopolitical occurrences. This is a fundamental problem. Before junior sailors can prepare for the high-end fight, they must have a deckplates understanding of great power competition. The Navy can use that understanding to motivate sailors and provide them with a genuine sense of purpose.

Existing organizations such as the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) can drive internal force messaging on current threats. Around 2015, ONI published unclassified primers on the Russian and Chinese navies.2 These documents should be updated and become annual productions, designed with low-bandwidth text-based distribution, as well as a high-bandwidth interactive version.

In addition, ONI should collaborate with the Chief of Information and Office of Information on quarterly periodicals designed to educate the fleet on current operations, technology, and tactics toward countering Russia and China. Although this undertaking must be balanced against operational security considerations, it would provide sailors a consumable product that directly correlates their experiences, training, and deployments to a wider global narrative. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy (MCPON) should endorse these products to reinforce their importance.

Internal Force Messaging

The CNO and MCPON have mentioned Ukraine only in passing since the beginning of the conflict. If internal force messaging were systemic in the Navy, the top brass would have recorded a speech addressing the Navy’s wardrooms and chief’s messes to inform deckplate leaders about what is likely the most historically significant global event since the fall of the Soviet Union. By building deckplate awareness of Russian and Chinese capabilities and intentions, the Navy could partly inoculate sailors against the shock of combat should it occur. When the USS Mason (DDG-87) was attacked by antiship cruise missiles in 2016, too many sailors remarked they “did not sign up for this” in reference to a warship actually being fired on.3 This is not a unique sentiment.

Acknowledging a threat’s existence will make sailors more likely to engage with training, drills, qualifications, and watchstanding with a sense of urgency, realizing that (1) they matter to the outcome, and (2) the outcome can be violent and consequential.

Beyond talking the talk of great power competition, the Navy must also walk the walk in how it leads and trains. For example, Afloat Training Group’s Final Battle Problem functions as a whole-of-ship training evolution in which many key “khaki belts” find themselves out of play, serving instead as various shipboard training team members.4 The Final Battle Problem should remain an important culminating event for the Navy’s Basic Phase training, but it should be followed up with no-notice at-sea training events characterized by a simulated threat for which the ship did not have time to prepare. These events could be run by an organization with access to the ship’s schematics and steeped in the lessons from the USS Cole (DDG-67), Stark (FFG-31), Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58), and other similar incidents. Recorded combat system data and deck logs could be turned in on return to port, and the debriefing process would roll into lessons learned.

A valid concern regarding this form of training is the inability of commanding officers to apply the operational risk management process to counterbalance sleep requirements, safety requirements, and pending operational or training commitments against an event over which they lack control.

Well, what do we think combat is?

The Pressure of Knowledge

The Navy’s enlisted personnel represent approximately 80 percent of the force, and they will be disproportionately fighting Russia and China should competition ignite into conflict.5 If conflict occurs within the next decade, then World War III veterans already are in uniform.6 While the probability of the Ukrainian war escalating into conflict between Russia and the United States is low, the probability of war with a nuclear-armed nation with a navy capable of attacking U.S. ships at sea has never been higher in the active-duty force’s lifetime.

Today’s sailors are recruited from a society that has never had to conceptualize a high-end war until 24 February. While Ukraine is not the first social media war, never before have such levels of carnage and violence been so widely disseminated.7 Sailors are being exposed to this reality with no little or no historical context or institutional lessons to guide them. At best, conflict will remain abstract, or at worst, sailors will feel demoralized and uncertain if we do not begin applying the pressure of knowledge now. We as leaders must control the narrative within the lifelines on these matters, but the Navy has not equipped us to do so.

The Navy cannot afford to wait until the first missiles and torpedoes of the next war at sea are launched to take a hard look at sailor awareness of the threat. By then it will be far too late to educate sailors and help them prepare. . . . at that point, they will just have to brace for the shock.

1. U.S. Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America; and Kathrine Kallehauge, “Global Peace Index 2021—A Year of Civil Unrest,” Impakter, 25 June 2021.

2. U.S. Department of Defense, “The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century,” 2015, www.oni.navy.mil/ONI-Reports/Foreign-Naval-Capabilities/China/; and U.S. Department of Defense, “The Russian Navy—A Historic Transition (2015),” Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015, www.oni.navy.mil/ONI-Reports/Foreign-Naval-Capabilities/Russia/.

3. PO1 John C. Minor, USN, “Every Sailor a Damage Controlman,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 8 (August 2019).

4. Megan Eckstein, “Surface Forces Striving for ‘Combat-Ready Ships, Battle-Minded Crews,’” USNI News, 4 September 2019.

5. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook: Military Careers, 18 April 2022.

6. Mallory Shelbourne, “Military Takeover of Taiwan Is Top Concern for INDOPACOM Nominee,” USNI News, 23 March 2021; and Phil Stewart, “Next Major World War Will Be ‘Very Different,’ Says U.S. Defense Secretary,” Reuters, 30 April 2021.

7. “The Invasion of Ukraine is Not the First Social Media War, But It is the Most Viral,” The Economist, 2 April 2022.