Flying, I think for anybody, has to be exhilarating, when you can go straight up or flip on your back, go straight down, or pull all kinds of Gs. You’re in a constant mode of competing and challenging yourself. You seldom run into an aviator who doesn’t like what he’s doing.1

So the late Chief of Naval Operations and carrier naval aviator Admiral Thomas B. Hayward described life as a lieutenant test pilot at Naval Air Test Center Patuxent River in 1954.

The Naval Institute has been covering carrier aviation since its early days, capturing the developments, the exhilaration, and all the ups and downs (literal and figurative) in Proceedings, Naval History, oral histories, and books from the Naval Institute Press. Following are some edited highlights.

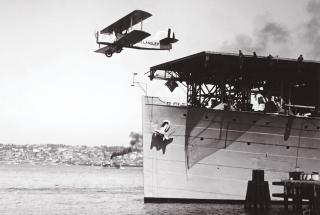

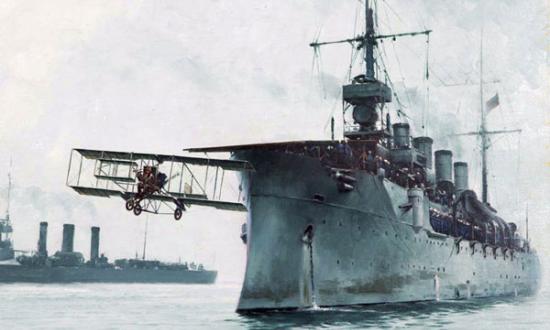

Eugene Ely established carrier aviation esprit in his pre-carrier 12 November 1910 launch from the 83-foot platform on the bow of the scout cruiser USS Birmingham (CS-2) and his 18 January 1911 landing on the 119-foot stern platform of the armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania (ACR-4). Dodging rainstorms on take-off day, ship still at anchor, Ely took his seat in his four-cylinder Curtiss biplane:

As his engine was gradually spun up to full speed, the powerful backdraft from the propeller so disconcerted the helmsman on the bridge, his face being directly behind the propeller, that it was doubtful whether he would be able to steer the ship from that position. Suddenly, while 20 fathoms of chain were still out, and without previous warning, Mr. Ely gave the signal to let go, and at 3:16 p.m., he quickly flew off the platform without having any assistance from the ship whatever in the matter of speed or lifting power. He had realized that weather conditions would not improve and had suddenly concluded to try the experiment from a standstill.

In his landing, Ely completed a turn at about 500 yards on the starboard side of the Pennsylvania and headed for the ship:

When about 75 yards astern it straightened up and came on board at a speed of about 40 miles an hour, landing plumb on the centerline, missing the first 11 lines attached to sandbags—but catching the next 11 and stopping with 30 feet to 50 feet to spare, nothing damaged in the least, not a bolt or a brace started, and Ely the coolest man on board.2

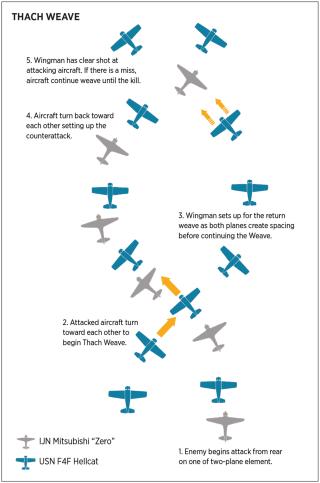

Carrier aviators have pioneered as they have flown, learning and mastering in the cockpit in an evolutionary chain of aircraft, from wheel and float biplanes to F/A-18E/F Super Hornets and F-35 Lightning IIs. They devised new offensive and defensive tactics such as the Thach Weave and helped to shape and innovate their carrier platforms.

The Navy’s first aircraft carrier, the USS Langley (CV-1), a former collier with a wooden flight deck added on top, was commissioned in 1922. In her precommissioning days, Lieutenant Commander Godfrey de Courcelles Chevalier, naval aviator number seven, made the first landing. Lieutenant Alfred M. Pride made the second. There was no provision for arresting gear in the carrier’s original plans. Chevalier “walked up to me one day,” Pride recalled, and said, “‘You make up a gear to stop the airplanes on the Langley.’ I said, ‘Aye, aye, sir,’ and that’s all there was to that.”

The ship first had wires across the deck with sandbags on either side. A plane would land, tailhook out, to snag wire after wire and drag more sandbags until it stopped. There also were longitudinal wires to be snagged by hooks to keep the plane from going over the ship’s side. In about six months, working with draftsmen in Norfolk, Pride developed a system of horizontal arresting wires attached to cast-iron weights suspended from the vertical steel columns supporting the flight deck. The longitudinal wires were eliminated.3

In 1927, the Langley was joined by the converted battlecruisers USS Lexington (CV-2) and Saratoga (CV-3) and, in 1934, by the USS Ranger (CV-4), built as a carrier from the keel up. Proceedings authors such as Lieutenant Commander Forrest Sherman—fighter pilot and future Chief of Naval Operations—were publishing on naval air. In his 1930 article “Fighters,” Sherman examined the pluses and minuses of single-seater and two-seater planes:

With planes diving at speeds near their terminal velocity and changing direction even slightly, the wind blast and forces of acceleration produced render it nearly impossible to operate the rear gun.4

Other officers were shaping carrier operations and doctrine. Captain Ernest J. King had earned his wings before taking command of the Lexington. In 1933, as a rear admiral and chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, he had decided that all officers preparing to take carrier command should first go through flight training. Lieutenant Roy Johnson was a Pensacola flight training instructor at the time:

Probably the most trouble I had with students happened to be with captains sent down there by Ernie King. We were flying the Vought scout plane, carrier type. I had John Sidney McCain as a student. . . . He couldn’t even taxi the airplane.

I took him out to shoot the circle. You would climb to 1,500 feet, cut the engine back, and glide down to land inside this 200-foot circle. I could see what he was doing cutting down to a glide over this farmhouse and then a road. When the wind changed 180 degrees, he couldn’t even land in the field let alone the circle. He’d lost all his check points. I asked him about it.

“The altimeter must have been out, son.”

When Bull Halsey went up with Evans as his instructor, he asked, “How do you take this thing off?”

“Well, Captain,” Evans said, “you get in there, you get all set, you head it down the runway. You give it full throttle, push the stick forward, and I defy you to keep that thing on the ground.”

Well off he went, and the next thing people saw was the plane up on its nose. They finally graduated all these people out of Pensacola.5

In 1937, Proceedings published Lieutenant Commander Logan Ramsey’s prescient “Aerial Attacks on Fleets at Anchor,” which spelled out why such an attack might be an enemy aerial group’s preferred option: target ships silhouetted, sitting ducks, unable to maneuver or effectively engage guns.6

On the morning of 7 December 1941, PBY flying boat aviator Lieutenant James Ogden emerged from his Ford Island shower, heard planes, looked out of his window, and saw black smoke coming from near his hangars. He recalled in his oral history:

I looked toward Barber’s Point and Ewa and here was a TBD torpedo plane steaming up. I said, Good God, that guy’s going against the course rules. It kept coming, approaching Pearl City over where the Pan Am docks were. Then he turned, headed right for me, dropped his torpedo, and I was watching the torpedo track coming across. About the same time, this guy ducked up over the Utah and banked by my window about 30 feet away. The thing that struck me particularly was the great big round meatballs on each of those wings.

When I arrived at our hangars, most of our planes that were out in the open were damaged or destroyed. Our skipper showed up. With pants over his pajamas he had dashed over to wing headquarters for instructions. There he had been given a search sector from the plan drawn up by operations officer Lieutenant Commander Logan Ramsey that morning after an earlier submarine sighting.7

In 1952, former Imperial Japanese Navy Captain Mitsuo Fuchida, who in December 1941 had commanded all air groups of the First Air Fleet, wrote “I Led the Attack on Pearl Harbor” for Proceedings. He included aerial photographs taken during the attack on battleship row, smoke rising from Hickam Field in the distance:

The more I heard about the plan the more astonishing it seemed. Torpedoes were to be used against ships in Pearl Harbor, a feat that seemed next to impossible in view of the water depth of only 12 meters and the harbor being not more than 500 meters in width. It was not until early November that the torpedo problem was finally solved by fixing additional fins to the torpedoes.

Why was 8 December chosen as X day? That was 7 December and Sunday, a day of rest, in Hawaii. Was this merely a bright idea to hit the U.S. Fleet off duty? No, it was not so simple as that. This day had been coordinated with the time of the Malayan operations, where air raids and landings were scheduled for dawn.

At 0530 on the flight deck, a green lamp was waved in a circle to signal “Take off!” Men lining the flight deck held their breath as the first plane took off just before the ship took a downward pitch. The next plane was already rolling forward. Thus did the first wave of 183 fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes take off from the six carriers.8

The U.S. Navy thought hard about how to mount a retaliatory strike quickly in response to the Japanese attack. The answer was the Doolittle Raid in April 1942, when the carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) launched 15 Army Air Forces B-25 bombers at Tokyo. Navy flight instructor Lieutenant Hank Miller was tapped to train Colonel Jimmy Doolittle’s bomber detachment how to launch from carriers:

Eglin Field, Florida, had been set aside for the work. I climbed into a B-25—I had never seen one—as copilot. I told them that when you make a carrier take-off, you held both feet on the brakes. For this plane we’ll try one-half flaps. I asked them how much manifold pressure we could hold on for—say 30 extra seconds—and put the stabilizer back three forths. With engine full bore, I told them to release the brakes.

They had been taking off at 110 miles an hour. On the first take-off with me, they observed an air speed of 65 to 67. They said, “That’s impossible.” I said, “Okay, we’ll try it again.” The second take-off the same way showed an air speed of 70. They were then convinced that a B-25 could take off at that slow speed.

For the run to Japan, the B-25 was going to be at 31,000 pounds—2,000 pounds over the maximum designed load. I checked out all the pilots for light loads, then intermediate, then the maximum load they would be taking on the raid. Everyone did pretty well.9

During World War II in the Pacific, David McCampbell became the Navy’s top ace with a total of 34 enemy planes destroyed, the greatest number during a single tour of combat duty. On 19 June 1944, in the first Battle of the Philippine Sea’s Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, he led the second group of F6F Hellcat fighters flying from the USS Essex (CV-9). The enemy had been detected about 120 miles away:

We must have hit that second strike out about 60 miles, and we simply tore into them. They had Zeros, and they had Jills, torpedo planes, and Judys, a beautiful little bomber.

For some reason, I missed the fighters. I picked up the Judys and concentrated on them. Fortunately, the last division that was with me, four planes, picked up the fighters and had a good time with them. I led the rest of my people down on the Judys.

I had so much speed I couldn’t hit the leader, but I did hit one of the tail-end Charlies. I attacked him thinking that I would knock him off, then go under him, and go to the other side and come up with altitude advantage and hit them from the other side. But the Judy I first hit blew up in my face, and I pulled up above him to avoid the debris.10

Vice Admiral Marc “Pete” Mitscher was in command of Task Force 58 when David McCampbell was flying from one of his carriers in the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. Mitscher had earned his wings in 1916, piloted NC-1 in 1919 for the Navy’s first transatlantic crossing and had nearly succeeded before fog forced him down, and had been awarded the Navy Cross.

In 1955, the Naval Institute Press’s biography The Magnificent Mitscher was reviewed in Proceedings by then–Rear Admiral Arleigh Burke, who had served as one of Mitscher’s chiefs of staff in the Pacific:

Admiral Mitscher did not claim to be brilliant. He did know though, in utmost detail, tactics, aviation, but above all, people. Although Admiral Mitscher kept a careful watch on the material condition of ships and aircraft, he devoted most of his attention to his people. This was the reason for his unusual success as a naval commander and as a leader.11

The biography captured Mitscher in action in the Philippine Sea, drawing from his after-action report. When the battle was at its crucial stage on 20 June 1944, Mitscher informed Fifth Fleet Commander Admiral Raymond Spruance that he intended to launch everything he had, and because the launch was at maximum range, it would be necessary to recover the aircraft after dark. A few minutes before sunset, Task Force 58 pilots found the enemy carriers. Their dive bombers and torpedo planes attacked:

Then the planes started home. It was very late, fuel tanks were almost dry. The pilots knew the task force was down there, but there was no way to distinguish the carriers.

Admiral Mitscher walked into Flag Plot and told Captain Burke, “Turn on the lights.”

Task Force 58 suddenly leaped from the darkness, temporarily visible to any nearby submarines. Searchlight beams climbed straight into the sky; others pointed toward the carrier decks. Glow lights outlined the decks; truck lights flashed on mastheads in the outer screen.

Said one carrier pilot, “The effect on the pilots left behind was magnetic. They stood open-mouthed for the sheer audacity of asking the Japanese to come get us. Then a spontaneous cheer went up. To hell with the Japs. Our pilots were not expendable.” Then the planes started coming in trying to locate their home ships. Mitscher said, “Tell ’em to land on any carrier.”12

Fast carrier task forces were an evolution of World War II. More big changes were underway. “The U.S. Navy is about to see the last of its reciprocating engine fighters,” Lieutenant Commander Malcolm Cagle wrote in 1948:

Commanding Air Group 15 on board the USS Essex (CV-9), David McCampbell became the Navy’s leading ace, ultimately credited with downing 34 Japanese aircraft. Naval History and Heritage Command Jets are about to take over. This year, the Navy has two squadrons of new jet fighter aircraft operating in the fleet—VF-17A operating the McDonnell FH Phantom in the Atlantic Fleet and VF-5A operating the FJ Fury in the Pacific Fleet. These planes have been successfully operated aboard carriers by fleet pilots. And next year, the Navy is purchasing only jet-driven fighters. Several other new planes are imminent: the F2H McDonnell Banshee, F6U Vought Sikorsky Pirate, F9F Grumman Panther, and the F3D and F7U. It is only the beginning.13

Captain John “Jimmy” Thach commanded the USS Sicily (CVE-118) during the Korean War. During World War II, impressed by reports of the superior maneuverability of the new Japanese Zero fighters, he had developed the Thach Weave, a tactical formation maneuver to help the slower F4F Wildcat in combat. Now, off Korea, he had high praise for his embarked Marine pilots’ ground attack support of Marines ashore:

The Marine forward air controller on the ground was often an aviator. One time, the controller said, “I just want one plane of the four to come down and make a dummy run. Don’t drop anything. I’m going to coach you onto a big gun, a piece of artillery that’s giving us a lot of trouble. I’m very close to it, but I can’t do anything about it.”

So the leader came down in his Corsair, and he was coached all the way down, the air controller practically flying the plane for him.

“Now do you see it?”

“Yes, I see it.”

“OK, then, go back up and come down and put a 500-pound bomb on it. But be very careful.”

So down he came and released his bomb, hit it, and it exploded.

The controller said, “Right on the button. That’s all; don’t need you anymore.”

The pilot answered, “Just a minute. While I was on the way down, on the right-hand side of my gunsight, I saw a big tank. I couldn’t see it all. It was under a bush, but how about that target?”

And the controller said, “I told you I was close. Let it alone; that tank is me.”14

In 1951, following a tour of Korean War bombing runs from the USS Princeton (CV-37), Lieutenant Commander Arthur “Ray” Hawkins returned to Corpus Christi to rejoin and take command of the Blue Angels. From 1948 to 1950, Hawkins had performed in the F8F Bearcat prop. Now, he and teammates were flying new F9F-5 Panthers down to the team from the factory:

Captain Jimmy Thach developed the Thach Weave as a tactic to counter the superior maneuverability of the Japanese Zero compared to the U.S. F4F Wildcat. Illustration by William S. Smith / Courtesy of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas I didn’t make it; the flying tail ran away from me. The airplane just nosed over and over at 42,000 feet. I started redding out with all those outside loop negative Gs. I blew myself, seat and all, right through the Plexiglas. I was at 32,000 feet with no oxygen and wanting to free fall, because that was the only way to get down quickly to an altitude where I could breathe.

I didn’t want to hit the ground passed out, so I deployed the chute and started to pass out again. It took about 22 minutes in the chute before I landed in a cotton patch just outside Pickens, Mississippi. The team planes were buzzing me. I gave them the “Roger” sign, spent the night in a Memphis hospital, then got back to Corpus. I had a few bruised ribs and frost-bitten ears, but I flew in a show six days later.15

One of the first seven Americans in space, naval aviator and test pilot Walter M. “Wally” Schirra Jr. was the only astronaut with Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions. In October 1965, Schirra and astronaut Tom Stafford were on board the two-man Gemini 6 spacecraft ready to launch and rendezvous with the Agena target vehicle—the first rendezvous of two spacecraft—but the Agena blew up before reaching orbit. People thought fast:

Gemini 7 was scheduled to begin a two-week mission in early December. If Gemini 6 could be sent up while Gemini 7 was still in orbit, we could rendezvous with Gemini 7 as the target vehicle. We were rescheduled to fly eight days after Frank Borman and Jim Lovell.

Gemini 6 finally made it into orbit on December 15. Over the Pacific, I turned the spacecraft 90 degrees and ignited the aft thrusters. By the end of the burn, we were in the same plane as Gemini 7. As we got within half a mile, I maneuvered with tender care. As we moved within 100 feet, it was necessary to stop our velocity, or we would have whizzed by.

All four of us were overjoyed. We had done something we had spent years preparing for. We flew in formation for three revolutions of the earth, moving from a range of 100 yards to just inches, window to window, nose to nose. I did an in-plane fly around of Gemini 7, like a crew chief inspecting an aircraft.

With the rendezvous completed, we were ready to come home. “Really a good job, Frank and Jim,” I said to Gemini 7. “We’ll see you at the beach.”16

Starting in the mid-1940s, new classes of aircraft carriers started entering the fleet. The angled-deck USS Midway (CVB-41) was commissioned in 1945, followed later that year and in 1947 by the Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVB-42) and Coral Sea (CVB-43). The Forrestal-class was next, with the Forrestal (CV-59) in 1955 and the Saratoga (CV-60) first to sea.

The Cold War was deepening, and the new carriers flying jets were part of the U.S. strategic deterrent. Lieutenant Commander Robert Dunn was on board the Saratoga in the Mediterranean flying A4D Skyhawks in 1962–63. His strategic deterrence mission was paramount:

The A4D was capable of delivering a nuclear weapon, and all the pilots were trained to do so. The carriers were part of the nation’s Single Integrated Operations Plan (SIOP) for nuclear war, and we all had SIOP targets.

We were told what target, what target time, the estimated launch point, and desired weapons burst. It was up to us to line it out, prepare strip charts, and plot intelligence data such as flak, missile sites and potential escape havens. It seemed our targets were always at extreme range with the possibility of return to the ship very dicey indeed. Thus was coined the phrase, “One plane, one engine, one bomb, one man, one way.”17

In the early 1960s, carrier aviators were flying in the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and Pacific. In 1961, Commander Albert Vito Jr. would write:

To illustrate the competence and versatility incorporated in the attack carrier’s combat air group, let us examine briefly the composition of today’s air group and the functions of its embarked squadrons. A Forrestal-class carrier, ready for deployment, carries 85 to 90 aircraft, including a utility plane and two helicopters. The air group consists of six squadrons, each of from 12 to 14 planes. The main battery of the attack carrier is her four attack squadrons, presently two squadrons of the high-performance, jet attack A4D Skyhawk, one squadron of the heavier, long-range A3D Skywarrior, and one squadron of the propeller-driven AD Skyraider. These aircraft perform the functions of attack on targets at sea and ashore with either conventional or nuclear weapons. They accomplish interdiction, close support of troops, armed reconnaissance, and amphibious support with a wide variety of weapons.18

The Skyhawk fought hard in the Vietnam War, and future Admiral Stanley Arthur spurred it on: 514 combat missions and combat awards including 11 Distinguished Flying Crosses and 51 Air Medals.

The A-4 was always my favorite airplane. You sort of strapped the airplane on. It was small. I had to squeeze hard to get in. In fact, my squadron gave me a great big shoehorn they had made for me. It was a very straightforward airplane to fly, and it had very nice manners. It was like driving a sports car.

In 1968, the Tet Offensive was a turning point in the war. We began to learn how to deal with SAMs, the surface-to-air missiles. The first thing you did was to broadcast its sighting. You tried to get the SAM nose on, because if you lost trail of it behind you, you didn’t know when to make a hard right. You would try to get the missile up in your front quarter so you had it on either side of your nose. You would watch until you thought you had to make a move. Then you had to make a dramatic move—usually down and under the SAM, to try to get it to go past you. If you went up, you’d let off too much airspeed. You needed energy, because the SAMs could pull more Gs than you could. But they were going a lot faster. Even if they could out-G you, they couldn’t always out-turn you.19

“Inasmuch as only single-engine aircraft were assigned to carrier duty and only multiengi-ne aircraft were used for reconnaissance work, the pilots soon began calling themselves either ‘single-engine’ pilots or ‘multiengine’ pilots,” recalled Navy Captain W. D. Toole Jr.:

Visual identity was the next step. This came into being prior to World War II and was evidenced by the

single-engine pilots adopting a headgear of cloth helmet and googles, whereas the multiengine pilots wore baseball caps.The first major identity breakthrough for either group occurred in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Single-engine pilots made a dramatic shift to the “hard-hat.” This large, distinctive type of headgear, closely resembling an oversized football helmet, was not only dashing but also the most positive method yet found for visually identifying a member of either group. Patrol aviators were so jealous of this innovation that they would not accept the new equipment, but only lengthened the bills of their ballcaps.20

One of the ships operating off Vietnam was the USS Enterprise (CVN-65), the Navy first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. “It almost goes without saying,” her first commanding officer, Captain Vincent de Poix, wrote in the June 1962 Proceedings, “that the high speed we can maintain continuously for long periods of time is not only a tactical but a strategic advantage. Much has been said about the fact that Enterprise makes no smoke. The greatest booster of this advantage are the pilots who land aboard.” De Poix had flown and fought from the first carrier Enterprise (CV-6) in World War II.21

In the early 1960s, the helicopter was coming of age as an antisubmarine warfare platform, as Lieutenant Commander Wayne Jensen noted:

Here was a platform that could not be sunk by a submarine. It had a sonar transducer that was not affected by movement through water. It had a relatively high speed of advance that would reduce the “time late” at distant submarine probability areas, many minutes before a Search Attack Unit composed of two or more destroyers could arrive on station.22

The H-3 was the Navy’s first antisubmarine helicopter equipped for both hunter and killer operations.

Then the A-7A Corsair II joined the fleet. “I had the good fortune to be the first fleet aviator to fly the airplane in Dallas in August 1966,” Commander James Hill wrote in Proceedings. “I was impressed with the airframe, the engine, and primarily with the completeness of the weapon systems. The aircraft is virtually capable of delivering all weapons in the Navy’s arsenal, with minimum configuration changes, and maintains a respectable self-defense posture while in all its attack configurations.”23

A decade later, William Powers heralded the arrival of the F-14:

There’s a new breed of cat on the prowl and, like all Toms, it has already run into its share of trouble. But, its admirers contend, before its nine lives are over, it will be universally acclaimed as the best of its breed.

The Tomcat is armed and equipped to counter aircraft either in an old-fashioned dogfight or in a long-range missile exchange. It can also destroy hostile ship-launched missiles.

The AWG-9 airborne weapon control system includes pulse/pulse-Doppler radar, data processors, a computer, an infrared receiver, and auxiliary components. It is monitored and controlled by a naval flight officer whose flight station is directly behind the pilot.

The sum is an aircraft which, as one F-14A pilot put it, “will fly the pants and shoot the wings off any likely adversary.”24

As the decades passed, following combat and near-combat missions over Grenada, Lebanon, and Syria, naval aviation celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1986. The October Proceedings captured cameos from past and present and looked to the future. Lieutenant Michael Dunn, assigned to VF-114 on board the “Big E” in the Mediterranean, wrote about two pilot buddies:

Two F-14 Tomcats in the skies near Fallon, Nevada. The F-14, first delivered to the Navy in the mid-1970s, served in the Gulf War, Iraq, and Afghanistan before retiring from active service in 2006. Credit: Christopher “Pops” Papaioanu Their job descriptions require them to enter the chaotic world of “flight ops,” and they love it, and they do it with fighter flair—catapulting off one end of the carrier and trapping on board the other. “When it’s dark,” says Nick, “I mean really dark—and its my turn to trap on board, the landing checklist goes something like this: Wings are at 20 degrees, gear three down and locked, Hail Mary, mother of God, please don’t let me bolter.” When it comes to a night carrier landing, there are no atheists in the cockpit.25

In “Becoming a Female Aviator,” Lieutenant Chrystal A. Lewis put her first steps and those of her classmate Suzanne Grubbs in perspective:

I knew from the outset that flight training at Pensacola was going to be great. I was on cloud nine. We worked our butts off, sweated bullets. We had our individual minor crises, of course. But we could lean on each other emotionally, and it was so nice to be out of the Academy and into an environment where women had already been accepted.

I still don’t understand why gals don’t jump at the chance to get into the aviation community where you can work with some of the most liberal men in the military. The Navy is very conservative, but the most easygoing guys, outgoing, open-minded people, in my opinion, biased as it is, are in naval aviation.26

In 1986, Lieutenant James A. Winnefeld Jr. looked to moves being made by Navy tactical air toward greater readiness for its role in the Maritime Strategy:

In the past year and a half, the Navy Fighter Weapons School (TOPGUN) has taken a critical look at its inputs to the Navy’s readiness equation, most of which occur in the areas of tactics and training. The resulting changes in TOPGUN’s structure and emphasis promise enormous benefits for Navy and Marine tactical aviation.

In today’s air combat arena, we cannot afford to “brush up” tactically at the last minute or to have to learn by many mistakes, for aircraft and aircrews are too expensive and take too long to develop. TOPGUN is but a single contributor to combat readiness in the Navy, yet it is better prepared now than ever before to do its part in ensuring that fleet aircrews will “get it right the first time.”27

The Navy’s F/A-18 was proving a remarkable attack/strike platform, noted Lieutenant Commander Matthew Boyne:

The F/A-18 Hornet provides the battle group commander another way to hit a target while minimizing losses. Suppose that in addition to the low-altitude attacks on Libya in April 1986, a flight of Hornets had gone in at 35,000 feet. . . . On the negative side this would have given up the element of surprise, allowing earlier readiness by the Libyan forces. On the positive side, the targeting problem for the enemy would have been severely complicated and the theater commander would have gained more strike aircraft because the single-seat Hornets were not considered capable of low-altitude night ingress. If the Libyan fighters had attempted to counter the high-altitude group they would have been defeated by the superior range and performance of the AIM-7 Sparrow missiles at high altitude.28

F/A-18 Hornets flying off carriers were part of strike missions in the Balkans in the 1990s and a strong arm of naval aviation for more than a decade. In his 1997 article “Super Hornet Is the Bridge,” Admiral Leon Edney sang the praises of the most recent F/A-18E/F models:

Carrier aviation and the F/A-18E/F are inextricably tied to the effectiveness of naval forward presence and power projection from the sea, well into the 21st century.

The E/F advantages over the C/D—in survivability, growth capability, significant tactical advantage provided by increased range, ordnance/fuel bring-back weight, mission payload, and the flexibility provided by the addition of the mission tanker capability—make the E/F the only choice if the effectiveness of the carrier battle group is to be maintained.29

On 11 September 2001, terrorists hijacked four civilian airliners and flew them into the twin towers of the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. Operation Enduring Freedom, the global war on terrorism, was soon in high gear, with F/A-18s, F-14s, and EA-6Bs making carrier launches and recoveries in the North Arabian Sea from the outset. Vice Admiral John Nathman would report:

Over the period of 7 October—the day of our first airstrikes into Afghanistan—to 16 December, when the Carl Vinson was relieved on station by the USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74), Task Force 50 flew nearly 4,000 strikes that delivered ordnance killing the enemy.30

Innovations and joint operations continued. Commander James Paulsen noted in the June 2003 Proceedings:

Recalling the techniques refined in the Vietnam War, the Kitty Hawk’s organic tanking capabilities would be tapped to their fullest potential. In Vietnam, A-4 Skyhawks that had flown from Yankee Station routinely returned to their carriers with enough fuel for only one pass before recovery tanking was required. This concept was employed for the Kitty Hawk’s returning F/A-18s. For the first time in more than a decade, the strike aircraft were allowed to return to their carrier with minimum fuel.31

In an interview in the same issue, Vice Admiral Timothy J. Keating, then–Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Central Command, and Commander, Fifth Fleet, commented on the airborne tanker challenge:

The S-3s were very important to our organic tanker capability. But with the F/A-18E/F, the Super Hornets, we have an organic tanking capability that is better suited to our mission than is the S-3. The Hornet can do mission tanking. It’s the same jet. It can carry five tanks of gas with a buddy store for the old tanking mission that some of us grew up doing. So these jets flew right up into Iraq with four Hornets with them, gave them each gas, flying the same profile.32

Over the decades, while the aviators kept flying missions, a debate ebbed and flowed on whether the aircraft carrier was the fighting heart of the fleet or a near-obsolete platform. Former CNO Admiral James Holloway III, who had commanded the Enterprise, weighed in hard in 2006:

Today, the U.S. carrier fleet is at a historic peak in its capabilities as the principal element of American sea power. This spectacular growth in their fighting capacity is not a theoretical set of premises or calculations. It is here today, demonstrated by recent combat operations against a real enemy on a large scale under measurable and observed conditions.33

Lieutenant Melissa A. Hawley was in those operations in Kuwait and southern Iraq flying MH-60S Seahawk helicopters in search-and-rescue and medevac operations in 2006:

During the following six months, we transported nearly 130 individuals, mostly at night. Sometimes days would go by and nothing, then we would have dozens of casualties.34

In 2013, F/A-18 pilot Lieutenant Commander Guy “Bus” Snodgrass took a few steps back to look at the major transition in naval aviation platforms underway:

Incorporation of the F-35 Lightning II into the air wing will introduce the first fifth-generation strike-fighter capability when it enters the fleet in 2019. By combining stealth with reduced electromagnetic emissions, the F-35 will provide the air wing with first-strike capability in contested and antiaccess environments.

The EA-18G Growler improves on the range, speed, persistence, and flexibility of the EA-6B, while also incorporating a much-needed air-to-air self-defense capability. The Growler combines the active electronically scanned array radar of the Super Hornet with the passive ESM capabilities from the late-model Prowler, providing drastic improvements to detection of surface and air targets.

The Pentagon crafted a roadmap that would replace multiple aging helicopter platforms. The MH-60R’s primary missions are ASW and ASuW, and the MH-60S is the “killer” because of its increased weapon capacity . . . and ability to provide swarm defense.

Naval aviation is using the current period of recapitalization to break from the Cold War–era mindset of platforms designed to support a single, primary role.35

In 2017, Marine F/A-18 pilot Major Michael T. Lippert challenged existing policy in “Life or Death in 250 Milliseconds”:

Mishaps cost the Navy and Marine Corps 40 F/A-18s between 2006 and 2016, resulting in 15 fatalities and $2.6 billion in losses. Fourteen of these events were because of controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) or were the results of mid-air collision. While CFIT and mid-air events accounted for only 35 percent of the incidents, they resulted in 50 percent of the cost, and 73 percent of the loss of life.

He discussed the research, development, and introduction of automated integrated collision avoidance systems (Auto-ICASs) currently in use—but not by the Navy or Marine Corps:

For the F/A-18 community, the threats of CFIT and mid-air collisions could be mitigated by leveraging current technologies that are fielded in civilian and Air Force aircraft. Installing Auto-ICAS across the F/A-18 fleet would save lives, aircraft, and money.36

His recommendations were heard higher up and acted on.

In 2019, there was cause for celebration. In “TOPGUN: The Navy’s First Center of Excellence,” Commander David Baranek marked the 50th anniversary of the Navy Fighter Weapons School, initially housed in a trailer at Naval Air Station Miramar, with the sign TOPGUN on its roof:

The need for a program to hone Navy fighter tactics became clear in the early years of the Vietnam War. U.S. Navy aircrews were flying the most modern fighters in the world—the F-4 Phantom II and F-8 Crusader—against a relatively primitive foe, yet the Navy’s kill ratio was only 2.5:1. In World War II, which had ended just 20 years before the air war in Vietnam started, the U. S. Navy’s kill ratio was 14:1.

Navy leaders ordered an in-depth study, which was led by aviator Captain Frank Ault and produced 104 recommendations, including the need to establish an “Advanced Fighter Weapons School”:

Each instructor had to become an expert on at least one assigned subject, such as the intricacies of radar-guided missiles or one-on-one maneuvering. To prepare, instructors focused on the most detailed intelligence available and sometimes attended specialized training. They were, after all, teaching aviators who would be taking lessons into combat.37

Proceedings celebrates the first 100 years of carrier aviation—and the role of the warrior-writers who explored aviation in our pages—and we look forward to the next 100 years of aviation in the open forum. Clear deck!

1. ADM Thomas B. Hayward, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 2009), 95–96.

2. CAPT W. Irving Chambers, USN, “Aviation and Aeroplanes,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 37, no. 1 (March 1911).

3. ADM Alfred M. Pride, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1984), 33–34.

4. LCDR Forrest Sherman, USN, “Fighters,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 56, no. 331 (September 1930).

5. ADM Roy L. Johnson, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1982), 29–31.

6. LCDR Logan C. Ramsey, USN, “Aerial Attacks on Fleets at Anchor,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 63, no. 8 (August 1937).

7. CAPT James R. Ogden, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1982), 48–52.

8. CAPT Mitsuo Fuchida, former IJN, “I Led the Attack on Pearl Harbor,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 78, no. 8 (September 1952).

9. RADM Henry L. “Hank” Miller, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1973), 32–33.

10. CAPT David McCampbell, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 2010), 179.

11. RADM Arleigh A. Burke, USN, The Magnificent Mitscher, book review, U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 81, no. 3 (March 1955).

12. Theodore Taylor, The Magnificent Mitscher (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1954), 232–35.

13. LCDR Malcolm W. Cagle, USN, “The Jets Are Coming,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 74, no. 11 (November 1948).

14. ADM John S. Thach, USN (Ret.), “Right on

the Button: Marine Close Air Support in Korea,”

U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 101, no. 11 (November 1975).

15. CAPT Arthur R. “Ray” Hawkins, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1983), 66–69.

16. Wally Schirra with Richard N. Billings, Schirra’s Space (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 158–65.

17. VADM Robert F. Dunn, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 2008), 184–85.

18. CDR Albert H. Vito Jr., USN, “The Attack Carrier—Mobile Might,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 87, no. 5 (May 1961).

19. ADM Stanley R. Arthur, USN (Ret.), Oral History Reminiscences (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 2017), 117, 137.

20. CAPT W. D. Toole Jr., USN, “Naval Aviators: The Old and the Bold,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 96, no. 1 (January 1970).

21. CAPT Vincent P. de Poix, USN, “The Big ‘E,’” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 88, no. 6 (June 1962).

22. LCDR Wayne L. Jensen, USN, “Helicopters in Antisubmarine Warfare,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 89, no. 7 (July 1963).

23. CDR James C. Hill, USN, “The Corsair II as I See It,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 94, no. 11 (November 1968).

24. William M. Powers, “F-14 Tomcat,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 102, no. 10 (October 1976).

25. LT Michael L. Dunn, USN, “The Naval Aviator,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 112, no. 10 (October 1986).

26. LT Chrystal A. Lewis, USN, “Becoming a Female Aviator,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 112, no. 10 (October 1986).

27. LT James A. Winnefeld Jr., USN, “Top Gun: Getting It Right,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 112, no. 10 (October 1986).

28. LCDR Matthew J. Boyne, USN, “Hornet on the Attack,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 116, no. 9 (September 1990).

29. ADM Leon A. Edney, USN (Ret.), “Super Hornet Is the Bridge,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 123, no. 9 (September 1997).

30. VADM John B. Nathman, USN, “‘We Were Great’: Navy Air in Afghanistan,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 128, no. 3 (March 2002).

31. CDR James Paulsen, USN, “Naval Aviation Delivered in Iraq,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 129, no. 6 (June 2003).

32. VADM Timothy Keating, USN, “This Was a Different War,” interview, U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 129, no. 6 (June 2003).

33. ADM James L Holloway III, USN (Ret.), “CVN=Indispensable National Asset,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 132, no. 9 (September 2006).

34. LT Melissa A. Hawley, USN, “Life from Above: Perspectives of a Navy ‘Blackjack’ Pilot,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 133, no. 12 (December 2007).

35. LCDR Guy M. Snodgrass, USN, “Naval Aviation’s Transition Starts with Why,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 139, no. 9 (September 2013).

36. Maj Michael T. Lippert, USMC, “Life or Death in 250 Milliseconds,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 143, no. 1 (January 2017).

37. CDR David Baranek, USN (Ret.), “TOPGUN: The Navy’s First Center of Excellence,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 9 (September 2019).