After two decades in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Marine Corps is getting ready to compete against pacing threats in the Far East. Commandant of the Marine Corps General David H. Berger has called for redesigning the force to meet current demands and to prepare for those anticipated in the future.In the 2021 Force Design 2030 update, he noted specifically the need to modernize health service support (HSS) “so that it is best suited for forward deployment and rapid response at the point of injury, maximizing the survival rate of wounded personnel.”1 To that end, the service should move from the current HSS structure and adopt an operational medicine team (OPMED-T) model.

The Existing HSS Model

The current HSS structure organic to Marine Corps infantry battalions (see Figure 1) is outdated and ill-suited to the service’s future distributed operating environment. Under this model, an infantry battalion can establish up to two battalion aid stations (BASs), capable of providing Role I care. If all force structure requirements were authorized and all manning levels mirrored the projected personnel end strength, the battalion could provide first responder and primary resuscitative care for approximately 50 casualties.2 This might be sufficient for a low-intensity conflict, but not to provide rapid response at or near the point of injury to maximize survival in a high-intensity environment. In war games against a near-peer or peer adversary in a noncontiguous battlespace, the existing HSS structure was unsustainable.

At lower echelons, such as rifle companies, the extent of medical care typically is within the scope of corpsmen. Corpsmen are capable first-line providers and essential elements of the Navy–Marine Corps team; however, their scope of practice generally is narrow. In most instances, without higher-level training, corpsmen cannot process acute or complex trauma cases at the point of injury, instead relying on the ability to evacuate high acuity patients within the “golden hour,” the first 60 minutes following a traumatic injury.3 In a near-peer or peer threat environment, counting on evacuation within the golden hour for responsive care is unrealistic.

Given the Marine Corps’ desire to maximize the survival rate of wounded personnel, the current medical structure must be revised well before the next fight.

In addition, among Fleet Marine Forces medical providers, a common complaint is being overburdened with administrative tasks, which hinders their ability to serve as primary care providers to several hundred Marines, as well as their ability to teach their corpsmen advanced medical procedures.4 Additional support providers would help mitigate burnout and streamline the healthcare-management system.

The OPMED-T Model

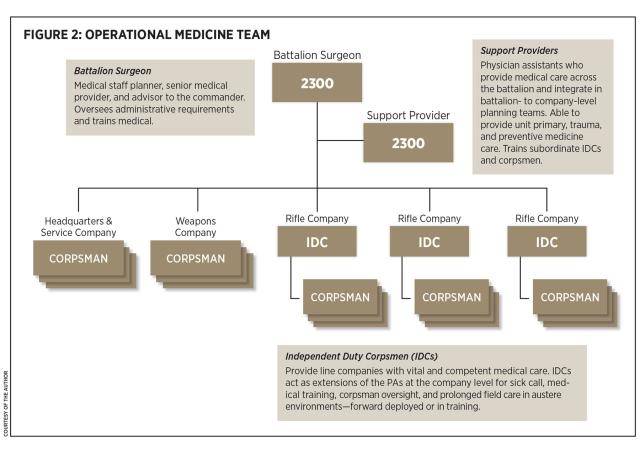

OPMED-T is a team-based approach that offers a solution to impending medical gaps within infantry battalions as the force prepares for a noncontiguous environment—specifically, expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO). As seen in Figure 2, the OPMED-T model bolsters the number of medical providers at all echelons of the battalion by calling on the physician assistant (PA) and independent duty corpsman (IDC) communities, who are able to provide higher acuity care. More important, while PAs provide a higher level of care at the battalion level, IDCs, working in tandem with their corpsmen, can provide infantry rifle companies resuscitative care at the point of injury during EABO.

The proposed model includes a dedicated battalion surgeon who would be the primary medical staff planner, coordinating with adjacent and higher medical units, as well as overseeing all administrative tasks. The support medical officer would be responsible for treating patients and training subordinate providers. The IDCs could help train subordinate corpsmen, as well as reduce the number of patients seen by the support medical officer by decentralizing higher-level care down to the individual rifle companies.

Under OPMED-T, the requirement for two medical officers remains; however, the 2100 operational medical officer (OMO, a licensed, practicing physician) is replaced with a second 2300 billeted PA. The PAs will provide care at the headquarters and service company, including the weapons company. At the rifle company level, IDCs and corpsmen can establish a BAS(-), with a smaller logistical footprint than the average BAS, to provide a Role 1(-)–capable facility. With OPMED-T, the PAs, IDCs, and corpsmen work in concert, enlarging the medical sphere of influence over the area of operation and coordinating with one another to ensure medical supplies are appropriately pushed or pulled.

Using PAs and IDCs to meet the need for more providers is not a novel concept. The IDC profession grew out of a World War II requirement for competent and capable medical providers well beyond the scope of hospital corpsmen, and PAs followed in the 1960s.5 As the Marine Corps prepares for great power competition, the OPMED-T model leverages existing providers, calling on PAs and IDCs to come together and perform their intended function of providing high levels of quality care throughout all echelons of the infantry battalion.

Staffing

Being able to provide both a 2100 and a 2300 clinician to each infantry battalion under the current HSS structure is idealistic. According to the Total Force Structure Division (TFSD), gaps in personnel stem from a discrepancy between the authorized number of medical officers allocated to the Marine Corps and the number of available medical officers.9 As TFSD explained, the Marine Corps may submit a requirement for a specified billet, and the Navy may even fund it, but it does not necessarily guarantee the Navy can fill the seat.Infantry battalions typically operate with only one provider because of this disparity.

Nevertheless, even with its demand for more medical providers at the front lines, the OPMED-T is a feasible model.

Under the current HSS design, the requirement for infantry battalions to have an OMO billet narrows the group of clinicians the Navy can—or is even willing to—provide. Physicians are highly trained providers who take significant time to produce. Already at the mercy of OMOs’ lengthy education, the Marine Corps is further handicapped by the limited specialties that serve within combat arms units: internal medicine, emergency medicine, and primary care.7 According to TFSD, altering a billet from an OMO to a PA may occur, but only when absolutely necessary.8

As called for in Force Design 2030, the Marine Corps is looking to maintain only 21 (versus 24) active infantry battalions.9 With this change, it would require a total of 42 PAs and 63 IDCs to reinforce each battalion to support the OPMED-T structure. These numbers may seem large, but there currently are 70 active-duty PAs serving within the Fleet Marine Force, only 23 of whom serve within an infantry unit.10 Moreover, according to the Navy, there currently are 1,015 surface force IDCs distributed across the Navy and Marine Corps.

Currently, 2d Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, is experimenting with a model similar to OPMED-T that calls for PAs to serve at the rifle company level—significantly increasing the demand for PAs from 43 under OPMED-T to 63.11 In contrast, OPMED-T recognizes the realities of manpower and personnel issues related to board-certified providers and fills critical gaps at the company level with extremely capable IDCs. In all, OPMED-T is a feasible model.

Restructuring the Marine Corps’ HSS structure within all the infantry battalions could not be accomplished overnight. Nevertheless, if the service wants to meet tomorrow’s challenges, it must continue pursuing reform of outdated concepts. It should adopt the OPMED-T design, bolstering throughput in healthcare management and delivering life-saving care at or near the point of injury to maximize the survival rate of wounded personnel.

1. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Force Design 2030 Annual Update (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, April 2021).

2. MCRP 3-40A.5, Health Service Support Field Reference Guide (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 2015).

3. Cpl James M. Mercure, USMC, “STP Extends the ‘Golden Hour’ to Keep Marines in the Fight,” featured news, 1st Marine Division, 7 October 2008.

4. Capt Paul Hwang, USMC, “Proliferating Combat Medical Readiness,” Google survey forms, 19 September 2021.

5. Matt Lyman, “A Brief History of the U.S. Navy Independent Duty Corpsman,” DVIDShub.net, 5 December 2014; and “AAPA History of the PA Profession,” Naval Association of Physician Assistants blog, 2 April 2017.

6. U.S. Marine Corps Total Force Structure Division, interview with the author, Quantico, Virginia, 19 October 2021.

7. Stephen Rogers, interview with author, Camp Lejeune, NC, 19 October 2021.

8. Total Force Structure Division interview.

9. Berger, Force Design 2030 Annual Update.

10. U.S. Navy, Medical Service Corps Monthly Specialty Report as of End-August 2021 (Falls Church, VA: Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 4 December 2021).

11. Rogers interview.