A city cannot survive without a determined force of first responders. These vigilant individuals are trained to meet emergent catastrophes. A U.S. Navy aircraft carrier must be similarly self-sustaining. It requires skilled teams of technicians and tradesmen to respond to damage incurred while at sea. These first responders—damage control (DC) repair parties—are crucial to the ship’s survival. They fight fires, react to power and propulsion damage, maintain watertight integrity, and patch the flight deck to keep aircraft flying. DC teams saved the USS Yorktown (CV-5) multiple times during and after the Battle of the Coral Sea and during the Battle of Midway, but details of their actions are rarely highlighted in battle accounts.

Evolution of Yorktown Damage Control

The focus on damage control and related characteristics within the design of carriers can be seen in specifications issued by the Bureau of Construction and Repair. Under the titles “Damage Control—Flooding and Sprinkling Systems” and “Fire Systems,” the Yorktown’s 1934 specifications indicate attention to the details of damage control for magazine flooding, hangar sprinkling, and water curtain deluge systems, as well as firefighting on board the ship.1

Along with design improvements, emphasis on ship survival during and after an enemy action was taught to U.S. Naval Academy midshipmen in the interwar years. One book available to them was Principles of Warship Construction and Damage Control, which was published while the Yorktown was being built. It contained the maxim “A comprehensive understanding of the principles of damage control is an essential part of the training of the young, as well as the experienced, naval officer.”2

The Yorktown had five area-centric DC parties, plus one shipwide repair party for extinguishing gasoline fires. Each party was poised to act quickly and independently (if necessary) during battle or times of danger—not only to fight fires and shore up damaged ship structures, but also to help keep vital boilers operating and electrical, piping, and ventilation systems functioning.

Crews included men such as Musician First Class Stanford E. Linzey, who was on board the carrier during her two major Pacific battles. He was assigned to DC Repair Party IV as a sound-powered telephone talker, providing communications between the party and the Damage Control Central operating station. Positions such as his were critical in identifying damaged areas, coordinating efforts of DC parties, and facilitating passage through the maze of smoke-filled compartments.3

The watertight design of the Yorktown was important to the DC crews positioned in the ship. The repair parties (RPs I, II, III, IV, V, and G) were stationed in key locations throughout the carrier to preclude a single hit from eliminating the carrier’s damage response capability.

In addition, damage control and overall carrier survivability benefited from small but significant design enhancements. Quick-opening and -closing scuttles in watertight hatches for emergency passage of personnel, and supplemental equipment to quickly transfer highly flammable aviation gasoline from aircraft and fuel lines, are two examples of such improvements.

Coral Sea Battle and Pearl Harbor Repairs

The Battle of the Coral Sea highlighted the seamanship of the Yorktown’s captain, Elliot Buckmaster, as the commanding officer (CO) avoided eight Japanese torpedoes using the carrier’s maneuverability and speed. According to Stanford Linzey, “Captain Buckmaster had been a destroyer skipper . . . and in the battle of the Coral Sea, he handled the large carrier as if it were a small destroyer.”4

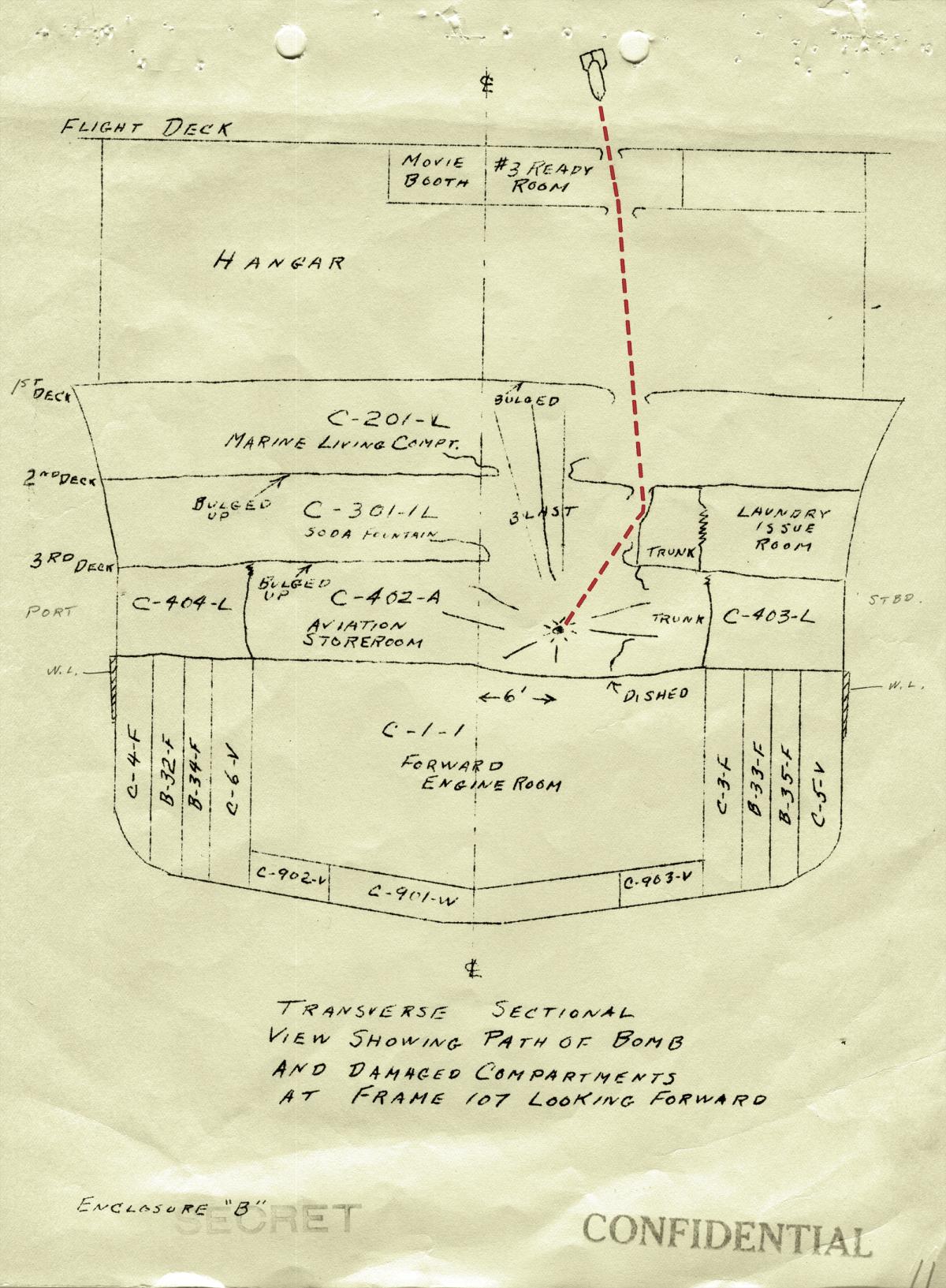

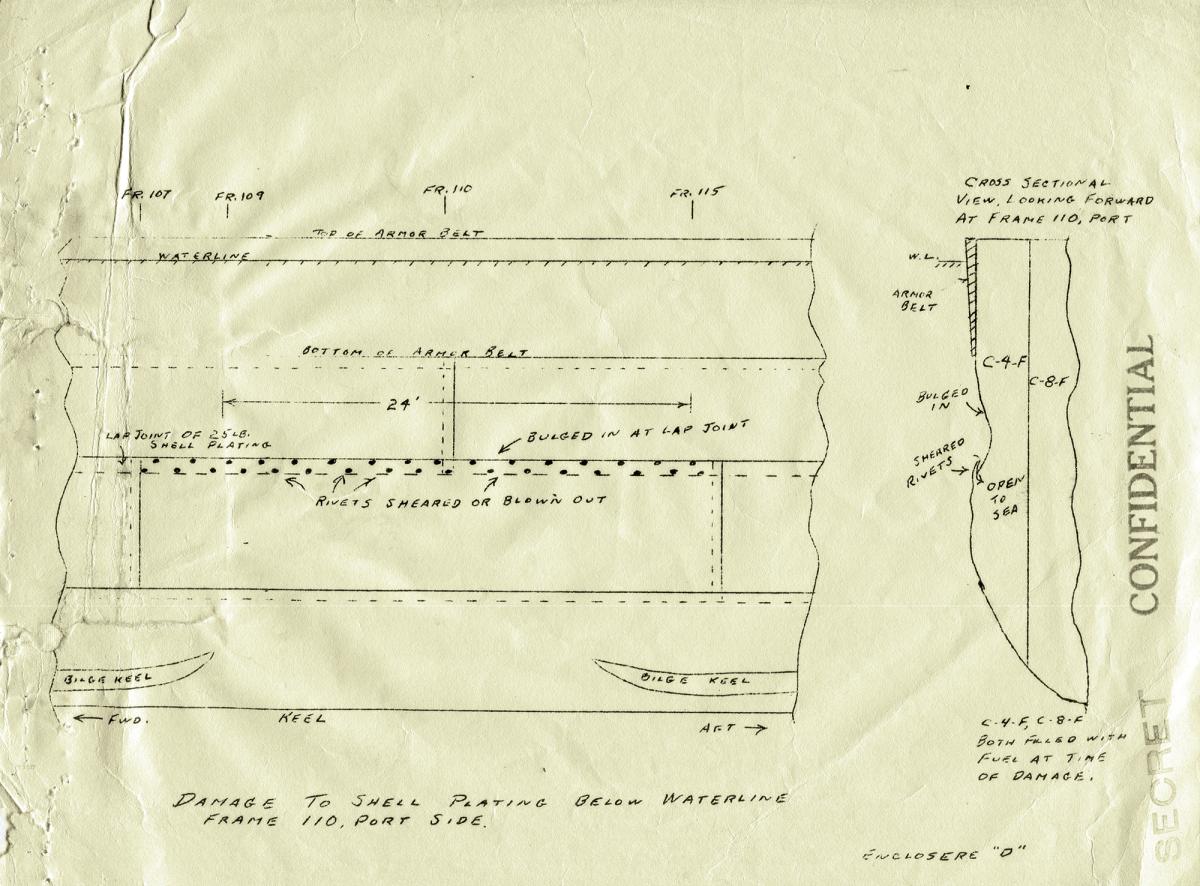

Despite the torpedo misses, the ship suffered one bomb hit and a near miss off the port side. The former caused significant internal damage, while the latter split open the exterior plating of the carrier and damaged the internal shell strengthening structure.5 The dislocated shell reinforcement left the ship’s hull weakened and subject to failure.

In his report on the damage suffered at Coral Sea, Buckmaster wrote:

Prompt action by the hangar repair party in quickly using fire hoses down through the bomb hole in the hangar and No. 2 elevator pit quickly brought the fire below deck under control. The Engineer Repair Party, Repair 5 . . . was completely wiped out with the exception of several wounded men. The Midship Repair Party, Repair 4, sent a fire party with rescue breathers into the smoke filled damaged compartment . . . cleared the wreckage and personnel casualties, then sent a man through the bomb hole down into [another compartment] where he extinguished the smoldering stores.6

The near miss on the carrier’s port side was more consequential. The dangers of a near miss were identified in 1924 when bombs were dropped near the uncompleted Washington (Battleship No. 47) “to evaluate the effect of underwater explosions caused by near misses of aerial bombs. Because of their intense pressure wave, the [near misses] were considered more dangerous than direct hits.”7

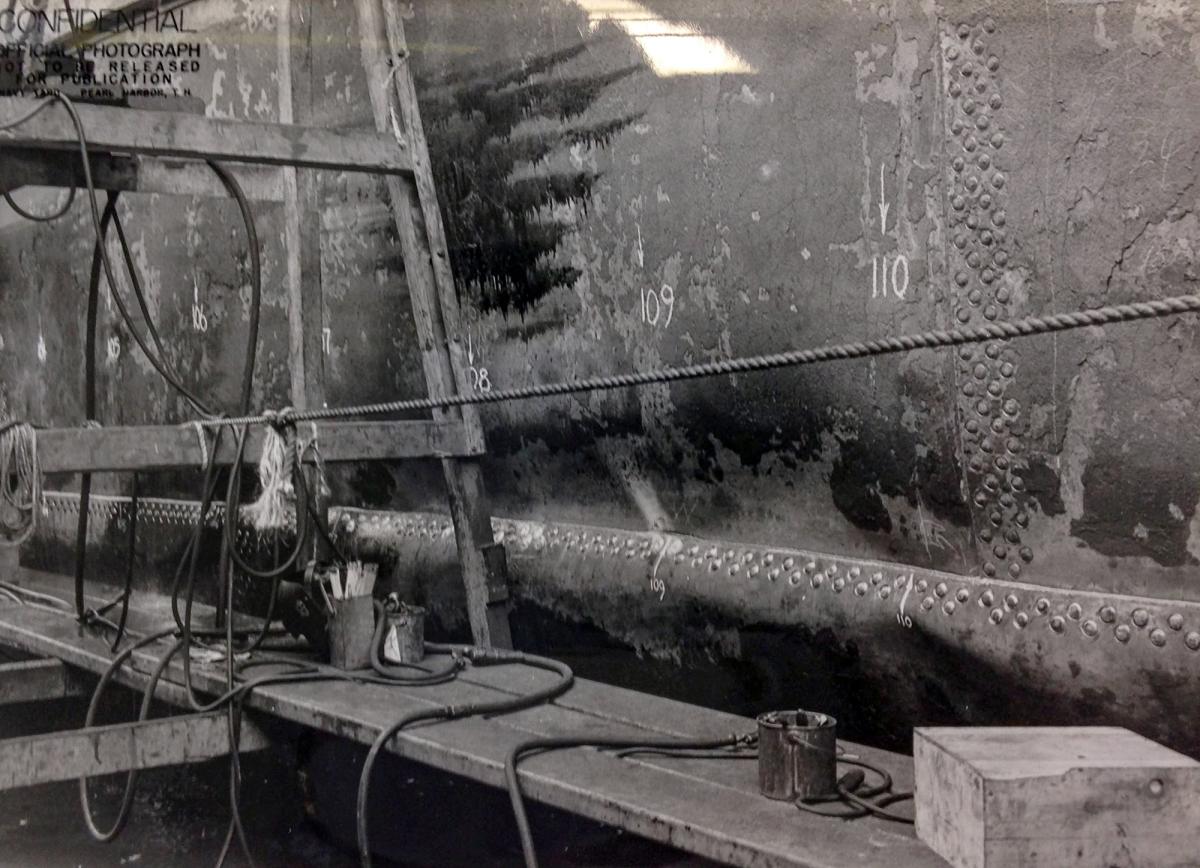

The Yorktown had a section of her port-side outer plating pushed in, and a 24-foot section of the shell plating was heavily damaged. Rivets along a lap joint in the area were “either sheared or blown completely out.”8 The shattered internal shell support structure could not be replaced in the brief time the carrier was in dry dock at Pearl Harbor. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, had directed that the Yorktown be seaworthy within 72 hours of her arrival. Nimitz’s headquarters (CinCPac) had been forewarned of a Japanese invasion force targeting Midway Atoll. Consequently, some internal repairs were postponed. The urgency of the carrier being on station with her aircraft outweighed completing the repair job.

The damaged shell plating was forced together and welded, in lieu of riveted, in place. This shortcut created fragile connections. The metallurgical composition of the plating was ill-suited for welding. The hastily performed lap weld on the shell plating put the ship at risk.

Linzey recalled:

[The] Yorktown came out of the dry dock as scheduled. The hull had been repaired, the third deck had been patched, the electrical systems were spliced, and the watertight doors and hatches had been replaced. However, three [of nine] boilers still were left inoperable because there was not enough time to repair them.9

The carrier’s flank speed would not be available to Buckmaster in the impending battle. Linzey and the rest of the crew knew the captain “had saved our lives by . . . maneuvering the great ship and avoiding the torpedoes, but now we were underpowered and incapable of such action.”10

Loss of the Yorktown

On the morning of 4 June, the Yorktown played a pivotal role at the Battle of Midway when SBD Dauntless dive bombers from the carrier, led by Lieutenant Commander Maxwell Leslie, sank the enemy aircraft carrier Sōryū. Meanwhile, SBDs from the USS Enterprise (CV-6) sank two more flattops, the Kaga and Akagi, leaving only one Japanese carrier, the Hiryū, to face three U.S. carriers.

Responding to the U.S. blows, the Hiryū launched two uncoordinated strikes. Shortly before 1100, 18 D3A “Val” dive bombers, escorted by 6 A6M Zero fighters, set out, followed two and a half hours later by 10 B5N “Kate” torpedo bombers, also escorted by 6 Zeros. The first carrier the Vals sighted was the Yorktown. Soon, the ship was rocked by three bomb hits and three near misses.11 Japanese aviators observed a burning, stationary wreck as they departed.

According to Buckmaster, the flight deck repair party “expeditiously” patched the holes from the direct hits. Fires were nearly all extinguished by RPs I, II, III, and VII within an hour and a half of the attack.12 The water curtain system in the hangar deck worked well. The

Yorktown had been making 25 knots prior to the bombing. With her boiler fires extinguished after a hit on the exhaust uptakes, the carrier now was motionless. But the engineering repair crew required a mere one hour to get her steaming at a respectable 23 knots.13 Fires were abated, smoke was evacuated, and flight operations were resumed.

The Yorktown’s acting executive officer, Commander Irving D. Wiltsie, later reported one reason the carrier had escaped more extensive damage: Shortly before the dive bombers had attacked, “all gasoline in the topside gasoline lines was pumped back down to the gasoline tanks. . . . [A] CO2 purging system for the topside gasoline lines and a CO2 blanket for the gasoline tank compartments” prevented a serious conflagration. Machinist Oscar W. Myers, the air fuel officer, had developed the carbon-dioxide purging system to expel vapors.14 This lesson had been learned from the loss of the USS Lexington (CV-2) at Coral Sea.

The pilots in the second wave of Japanese attackers had been instructed to target an undamaged carrier, not the doomed hulk the dive bombers had left burning. But as the Kate torpedo planes approached the Yorktown, the aviators found an operational ship. Surely, they had discovered an undamaged carrier.

At about 1430, the Japanese aircraft began their descent on the carrier and soon split into two groups to execute a “hammer and anvil” tactic, attacking the Yorktown on both port and starboard sides. Given the ship’s reduced speed, evading the coordinated incoming planes’ torpedoes was challenging. Two “fish” slammed into the port side of the ship near frames 80 and 92, tearing huge gashes in the hull. The hastily repaired 24-foot seam on her shell likely reopened. Captain Buckmaster reported “frame 70 to . . . 110 open to the sea.”15 Major flooding ensued, and the ship settled.

With no steam or electric power to counter the flooding, the CO reviewed the ship’s condition with his DC officer, Commander Clarence Aldrich, and his engineering officer, Lieutenant Commander John F. Delaney Jr. Concerned she might capsize, Buckmaster ordered the crew to abandon ship. Sailors secured watertight closures while evacuating the listing, darkened ship. Scuttles in the heavy (and frequently jammed) watertight hatches enabled otherwise trapped men to exit. Linzey noted:

The watertight hatch to the second deck was warped shut by the explosions. . . . [In] the center of each watertight hatch there was a scuttle, a small circular quick-acting hatch that could be opened by the turn of a wheel. . . . [T]he first man got it open, and the rest of us climbed up through the manhole, each in turn, one at a time.16

The Yorktown was the flagship of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the commander of the Midway Carrier Striking Force and Task Force 17, and he knew her well. Fletcher remarked in his after-action report that the men “started abandoning ship in anticipation of her capsizing and [potential] further enemy attacks. About twenty-three hundred survivors were picked up by destroyers.”17 Efficient damage control yielded a crew survival rate exceeding 90 percent.

After she was abandoned, the Yorktown remained afloat, and the next day, two wounded men were rescued from her. The tug Vireo (AT-144) secured a line to the carrier, and at 1636 she was in tow at about 2 knots. Early on 6 June, Buckmaster called for salvage party volunteers; 26 officers and 149 enlisted men returned to their stricken ship. “They knew full well that she was barely seaworthy and would probably be the target of repeated submarine and air attacks during a journey of some 1,000 miles,” Commander Wiltsie reported.18

The salvage party improved the ship’s list by 2 degrees from her prior 26 degrees using temporary pumps plus dewatering pumps from the destroyer USS Hammann (DD-412). Meanwhile, engineers worked on the Yorktown’s boilers. As the volunteers made progress, Japanese submarine I-168 positioned herself nearby and prepared a spread of torpedoes. By the time the fish were spotted at 1536, reaction was impossible. One struck the Hammann, splitting her in two. As she sank, her armed depth charges detonated; the explosions “shook Yorktown from stem to stern,” according to a volunteer, Petty Officer Second Class William G. Roy.19

The worst was yet to come. Two more I-168 torpedoes smashed into the ship’s vulnerable bottom on her starboard side. The Yorktown was bracketed by five major shell breaches near midship, plus the forces from the Hammann’s depth charges. Five main transverse watertight bulkheads at frames 71, 82, 90, 98, and 106 likely were compromised. The integrity of the center of the ship was fatally jeopardized. Buckmaster ordered the salvage crew off the derelict ship and the tow cast off.

With the huge hole punched in her underside, the Yorktown began to settle during the night, and near dawn took on a heavier list to port. At 0658, the ship rolled and capsized, exposing the massive wound in her bottom shell. Her gallant fight over, the carrier sank, settling nearly upright on the bottom of the Pacific.

In a postmortem, the Bureau of Ships concluded the submarine torpedoes induced disastrous flooding into the ship’s starboard boiler rooms and adjacent spaces. With numerous watertight boundaries compromised, the Yorktown stood no chance of recovery.

Damage Control Changes

As is the case after every major ship sinking, lessons were learned. Damage control procedural changes resulted from the loss of the Yorktown. The fundamental principle learned was “All hands, from the Commanding Officer down, must be made thoroughly conversant with all phases of damage control which apply to their own ship.”20 With that, instruction in firefighting became an integral part of Navy training for enlistees at boot camp, midshipmen at the Naval Academy, and ships’ companies while under way. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison noted that damage control efforts benefited throughout the duration of the war because of “the fire-fighting schools and improved techniques instituted by the Navy in 1942–1943.”21

Procedures instituted for purging gasoline lines with carbon dioxide circumvented losses from calamitous fuel fires. In his Midway report, Admiral Nimitz stated: “Gasoline fires in carriers are a serious menace. Yorktown, though hit by three bombs and set afire, had no gasoline fires, possibly because of the effective use of CO2 in the gasoline system.”22 Pumping inert gas into gasoline lines and tanks was adopted by the Navy, thanks to Machinist Myers’ innovation.

By the end of June 1942, CinCPac had ordered that salvage parties be instituted on board ships. According to the mandate: “In the event a ship receives such severe battle damage that abandonment may be a possibility, a skeletonized crew to effect rescue of the ship shall be ready either to remain on board or to be placed in an attendant vessel.”23

Further, design changes and better shipbuilding, welding materials, techniques, and qualifications were implemented. These resulted in more robust warships for the Navy. It became standard to provide temporary powered pumps and power-generation equipment for use on board ships after loss of power. Replacement of flammable interior paint with fire retardant paints to prevent oil-based paint fires was directed. The outfitting of damage control repair parties evolved with the introduction of more effective breathing apparatus, repair equipment, and personal protection gear.

The Navy learned lessons and implemented solutions after the Yorktown’s experiences at Coral Sea and Midway. Damage control had minimized the loss of life on board the carrier and left a legacy that helped reduce future U.S. casualties and ship losses.

1. Detail Specifications for Building Aircraft Carrier No. 5—YORKTOWN/No. 6 ENTERPRISE for the United States Navy (Navy Department Bureau of Construction and Repair, 15 February 1934), National Archives and Records Administration,

College Park, MD (hereafter NARA).

2. G. C. Manning and T. L. Schumacher, Principles of Warship Construction and Damage Control (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, reprinted 1939 with corrections), x.

3. Standford E. Linzey, USS Yorktown at Midway: The Sinking of the USS Yorktown (CV-5) and the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway (Maitland, FL: Xulon Press, 2004), 86–87.

4. Linzey, USS Yorktown, 88–89.

5. USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 20 May 1942, included in USS Yorktown (CV-5) Action Reports, Record Group 38, NARA.

6. USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 20 May 1942.

7. William M. McBride, Technological Change and the United States Navy, 1865–1945 (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 147.

8. USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 20 May 1942.

9. Linzey, USS Yorktown, 102.

10. Linzey, 106–7. The commanding officer reported 30 knots while evading torpedoes before losing Fire Rooms 7, 8, and 9 at Coral Sea (USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 20 May 1942).

11. Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2005), 262–63, 290–92, 295–97.

12. The Yorktown originally had six damage control crews (five area-centric and one for gasoline fires). Likely the loss of Repair V at Coral Sea because of the direct bomb hit resulted in a temporary Repair VII being mobilized.

13. USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 18 June 1942, War Damage Reports and Related Records, 1942–1949, Record Group 19, NARA.

14. Executive Officer to Commanding Officer USS Yorktown CV5, Subject: Executive Officer’s Report of Action for Period of June 4–7, 1942, 16 June 1942 (hereafter XO report), USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 18 June 1942.

15. USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 18 June 1942.

16. Linzey, USS Yorktown, 118.

17. RADM Frank Jack Fletcher, Battle of Midway: 4–7 June 1942, Online Action Reports: Commander Cruisers, Pacific Fleet of 14 June 1942.

18. Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Loss of Yorktown, 30 June 1942, Fold3.com [login required]. XO report, USS Yorktown, War Damage Report, 18 June 1942.

19. William G. Roy interview, The National WWII Museum.

20. U.S. Navy, Handbook on Damage Control (1945), 190.

21. Samuel Eliot Morison, Victory in the Pacific 1945, vol. 14, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1960), 98–99.

22. ADM Chester Nimitz, Battle of Midway: 4–7 June 1942, Online Action Reports: Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, Serial 01849 of 28 June 1942, 27.

23. Quoted in Samuel Eliot Morison, Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions, vol. 4, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1949), 156.