Maritime counterinsurgency is having a moment. Since at least 2018, professional national security journals and websites have devoted increasing attention to articles discussing the supposed threat of “maritime insurgency.”1 The maritime insurgency concept is composed of three core tenets. First, a U.S. adversary—China—is conducting a maritime insurgency. Second, the existence of this insurgency demands a U.S. counterinsurgency response. Third, this contest will play to U.S. strengths in counterinsurgency (COIN) operations, as developed and refined in previous U.S. wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. Maritime COIN proponents argue its relevance for all three Sea Services and have enjoyed professional acclaim, including winning the Naval Institute’s 2019 General Prize.3 They are articulate and provocative. They are also wrong.

Each tenet is mistaken. China’s actions in the South China Sea, however threatening, are not an insurgency, without which there is nothing for a maritime counterinsurgency to counter. Nor should the United States want to again play counterinsurgent, a role in which it has repeatedly failed. Maritime counterinsurgency is a flawed concept that adds nothing to U.S. strategy.

Myth 1: The Maritime Insurgency

boat during the Vietnam War. The author argues that advocates

of the counterinsurgency thesis overlook a critical fact: U.S.

counterinsurgency efforts in Vietnam (and Iraq and Afghanistan)

ended in failure. Credit: U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

The maritime COIN constituency is clear regarding the perceived urgency of the maritime insurgency threat:

- “It is no secret that China is waging a maritime insurgency in the South China Sea, terrorizing civilian mariners and foreign navies alike in a campaign to claim international waters as Chinese sovereign territory.”4

- “China is waging a ‘maritime insurgency’ that seeks to snuff out freedom of the sea and overthrow the U.S.- backed system of international law that upholds it.”5

- “China is waging a maritime insurgency in the South China Sea, working to brusquely subjugate and coerce the more than 3.7 million people in Southeast Asia who depend on access to those waters for their daily livelihoods.”6

These statements treat the existence of a Chinese-directed maritime insurgency as fact. Their authors describe Chinese objectives without explaining how Chinese tactics constitute “insurgency,” or even what an insurgency is. Put differently, they keep using the word “insurgency”—but it does not mean what they think it means.7

Of course, the term “insurgency” does have a meaning. It is “a struggle for control and influence, generally from a position of relative weakness, outside existing state institutions.”8 It is an effort by a subnational group to cast off the existing government. Historical examples include the Vietcong (opposing the South Vietnamese government); the Taliban (opposing the Afghanistan government); and the American colonists (opposing British rule). The Vietcong, Taliban, and colonists were insurgents, and the governments they opposed practiced counterinsurgency: “military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionaries.”9

An insurgency is thus an intrastate armed conflict between an insurgent group and a government. Because people and governments exist on land, insurgencies and counterinsurgency operations primarily take place on and over land, although maritime forces sometimes play an important supporting role.10 Of course, a state can support an insurgency in another state (as communist nations supported the Vietcong. or as the United States supported the Nicaraguan contras), and it is possible to imagine scenarios in which China or Russia might sponsor insurgencies against U.S. allies. In such cases, the United States might well be forced to conduct or support counterinsurgency operations to protect its national interests.

Today, great power competitors China and Russia repeatedly challenge the United States, its allies, and the international order by using (or threatening to use) their armed forces against regional rivals. Such conduct is serious and troubling, but it is state action—not insurgency. To proponents of maritime COIN, however, the term “insurgency” has expanded to encompass all bad behavior by U.S. adversaries. This includes the following examples:

- A nation-state “imposing extralegal authority on local civilian mariners . .. through implicit and explicit threats of force”11

- A nation-state attempting to “overturn the rule of international law that enshrines freedom of the seas”12

- One nation-state attacking another’s naval vessels “without provocation.”13

These are all bad actions, but they are bad actions by nation-states using traditional elements of national power. The first could describe Royal Navy impressment of U.S. sailors in the early 19th century; the second, German unrestricted submarine warfare in World War I; and the third. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. To characterize these actions by great powers as examples of insurgency would render the term meaningless.

In the South China Sea, China uses its armed forces (navy, coast guard, and maritime militia) in furtherance of its national objectives.14 This is traditional great power behavior, not insurgency.

Myth 2: The Counterinsurgency Imperative

Having incorrectly identified Chinese actions in the South China Sea as an insurgency, advocates of maritime COIN propose a U.S. counterinsurgency response.15 The U.S. military defines counterinsurgency, unsurprisingly, as “efforts designed to simultaneously defeat and contain insurgency.”16 In the view of the COIN advocates, the United States “must think and operate like a counterinsurgent in the South China Sea” or even “position itself between [China] and the South China Sea nations by establishing a Maritime Counterinsurgency.”17 But where no insurgency exists, there can be no counterinsurgency.

Indeed, a COIN response to Chinese actions in the region would be misguided and dangerous. The South China Sea is a complex region, with territorial disputes involving a half-dozen nations.18 The United States has different relationships with and obligations to each. For example, the United States is obligated by treaty to respond with force to a Chinese attack on the Philippines.19 However, in the case of a dispute between China and a rival such as Vietnam or Malaysia, the United States might choose to respond differently or not at all. By treating each incident and each relationship as distinct, the United States can best preserve its options and protect its interests

The maritime COIN concept lacks this flexibility. By characterizing all Chinese bad behavior as a monolithic "insurgency” to be “countered,” it risks entangling the United States in regional disputes that do not implicate U.S. national interests. One need not approve of Chinese behavior to question whether U.S. forces should intervene to prevent China from harassing Vietnamese fishing boats or Malaysian hydrocarbon research vessels.20 This false imperative to counter the supposed South China Sea insurgency is not merely wrong, but dangerous.

Myth 3: Defeat Into Victory

Finally, maritime COIN proponents believe the United States is good at counterinsurgency. If we must prepare to fight China (they argue), why not leverage this advantage?

For example, to counter the "overriding strategic challenge” posed by China, one Marine author would deemphasize sea denial and operations with the fleet in favor of “small wars training” and small-unit counterinsurgency tactics.21 This would, in his view, tap the Marine Corps’ “long tradition of excellence in low-intensity conflict, from the Banana Wars to the [Vietnam War’s] Combined Action Platoons”—and, of course, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, during which, "over the past 18 years, the Army and Marine Corps have learned how to cat soup with a knife in counter-insurgencies.”22

However well-intentioned, this argument ignores a critical fact: U.S. counterinsurgency efforts in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan ended in “tragic, multi-trillion dollar failures.”23 By embracing COIN as the preferred American way of war, the United States would ignore this history. No honest person can doubt the bravery and ingenuity of individual soldiers and Marines who learned "to eat soup with a knife” in Iraq and Afghanistan, but no sane person would seek to recreate the results of those wars.

Another Marine proponent of maritime COIN suggests that U.S. naval intelligence could leverage intelligence successes from the war in Afghanistan to analyze Asian maritime forces—and that, in doing so, it would address "considerations unique to COIN.”24 Without question, the services should learn and carry forward best practices from past wars. However, simply because a tactic, technique, or procedure worked well during a counterinsurgency operation, it does not follow that the practice is "unique to COIN.” In fact, the study of foreign maritime forces is, always has been, and always will be among the fundamental missions of any intelligence service. It should go without saying that U.S. naval intelligence should strive to understand Vietnam’s navy and China’s maritime militia, not as some kind of special COIN technique, but simply because that is its job.

Reframe The Problem

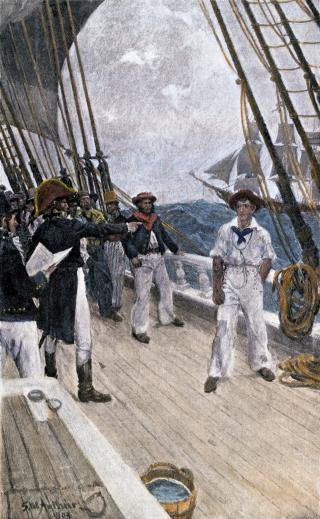

The British fourth-rate Leopard (right) fires on the U.S. frigate Chesapeake before forcing her to heave to and receive a British boarding party in 1807. Force majeure has long been a tactic stronger powers use to compel behavior by weaker ones, and it bears little resemblance to insurgency.

The United States faces many security challenges, but a maritime insurgency is not one of them. It is impossible to counter a Chinese (or Russian) maritime insurgency where none exists. Although it might be wise to prepare for future counterinsurgency operations, the United States should never again participate in a counterinsurgency by choice. As described in Proceedings and other professional naval publications, maritime counterinsurgency is a myth.

1800s. Though maritime insurgency thinkers in part define such

behavior as “imposing extralegal authority on local civilian

mariners . . . through implicit and explicit threats of force,” this

equally describes British behavior toward the United States for

many years after U.S. independence. Credit: Alamy / Northwind Picture Archive

To understand and address the challenges of the coming decade, U.S. strategists must think and speak precisely. This means abandoning the overbroad and confusing language of the maritime COIN concept and refocusing the strategic dialogue to frame the great power threat more accurately, and thereby suggest appropriate U.S. responses.

As the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine shows, nation-state conflict forces policymakers to confront the distinction between peace and war. This distinction, blurred by terms such as “gray zone,” as well as the maritime COIN concept, becomes painfully obvious when the adversary is capable of striking the United States with nuclear weapons. True counterinsurgency is a type of armed conflict, and armed conflict with Russia or China risks nuclear war.

Instead of seeking a third way of great power competition—somewhere between peace and war—the United States should seek to use national power to preserve peace, while preparing for war if deterrence fails. In peacetime, this means that diplomats will typically be the main effort, leveraging alliances, international institutions, and U.S. industrial and economic power to confront Russia and China while staying out of war. For example, the Ukraine crisis has shown the power of U.S. and NATO security force assistance as a tool to degrade a great-power adversary without being pulled into direct conflict. This should inform U.S. strategy for future great-power competition, whether in Europe or the Indo-Pacific.

- 1. U.S. Army and Marine Corps, Field Manual 3-24/Marine Corps Warfighting Publication 3-33.5: Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies (May 2014), para. 1-4.

- 2. Patrick M. Cronin and Hunter Stires, “China Is Waging a Maritime Insurgency in the South China Sea. It’s Time for the United States to Counter It,” The National Interest, 6 August 2018.

- 3. Hunter Stires, “The South China Sea Needs a COIN Toss,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 5 (May 2019); Maj Brian Kerg, USMC, “Naval Intelligence for Maritime COIN,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 4 (April 2021); and Lawrence Hajek, “Countering China’s Maritime Insurgency with Coast Guard Deployable Forces,” CIMSEC.org, 15 June 2021.

- 4. Kerg, “Naval Intelligence for Maritime COIN.”

- 5. Hunter Stires, “Win Without Fighting,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 5 (May 2021).

- 6. CAPT Dan Straub, USN, and Hunter Stires, “Littoral Combat Ships for Maritime COIN,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 1 (January 2021).

- 7. The Princess Bride, Rob Reiner, dir. (20th Century Fox, 1987).

- 8. Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies, para. 1-3.

- 9. M. Chris Mason, “COIN Doctrine Is Wrong,” Parameters, 51, no. 2 (Summer 2021), quoting the Oxford English Dictionary.

- 10. The Royal Navy’s support to British land forces during the American Revolution is a classic example of how maritime power can augment land-based counterinsurgency operations.

- 11. Cronin and Stires, “China Is Waging a Maritime Insurgency.”

- 12. Straub and Stires, “Littoral Combat Ships.”

- 13. Kerg, “Naval Intelligence for Maritime COIN.”

- 14. Andrew S. Erickson, “Numbers Matter: China’s Three ‘Navies’ Each Have the World’s Most Ships,” The National Interest, 26 February 2018.

- 15. See, Straub and Stires, “Littoral Combat Ships.” (“The U.S. Pacific Fleet is embracing its role in countering China’s maritime insurgency against the rule of international law and freedom of the seas.”)

- 16. Department of Defense, DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: November 2021).

- 17. Cronin and Stires, “China Is Waging a Maritime Insurgency,” and Hajek, “Countering China’s Maritime Insurgency.”

- 18. “Troubled Waters in South China Sea,” Straits Times, 29 February 2016.

- 19. Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines, 30 August 1951.

- 20. Sam LaGrone, “Report: Chinese Navy Warship Rammed Two Vietnamese Fishing Vessels,” USNI News, 7 August 2015; and Amy Chew, “China Harasses Malaysian Oil and Gas Vessels on a ‘Daily’ Basis,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative Says,” South China Morning Post, 25 October 2021.

- John Vrolyk, “Insurgency, Not War, Is China’s Most Likely Course of Action,” War on the Rocks, 19 December 2019.

- Vrolyk, “Insurgency, Not War.”

- M. Chris Mason, “Nation-building Is an Oxymoron,” Parameters 46, no. 1 (Spring 2016).

- Kerg, “Naval Intelligence for Maritime COIN.”