A growing quasi-consensus has emerged in Washington on the potential threat posed by the People’s Republic of China to U.S. interests in the Indo-Pacific.1 In particular, many analysts are concerned with the defense of Taiwan.2 In March 2021, Admiral Phil Davidson, the now former commander of U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific, stated, “I think the threat [to Taiwan] is manifest during this decade, in fact in the next six years.”3 Recent battles over the fiscal year 2022 budget have highlighted the unease many feel toward the U.S. military’s ability to meet wartime demands against a capable adversary.4

Nowhere does this seem truer than in the U.S. Navy. Specifically, many cite a combination of two factors contributing to this unease: declining ship numbers and the lack of a discernible strategy.5 During a 15 June 2021 House Armed Services Committee meeting, Representative Elaine Luria expressed her frustration, stating, “We’re continuing to shrink, and we’re continuing to divest-to-invest with strategies and capabilities that are just a hope for the future.”6 All arguments seem to point toward the need for a naval shipbuilding program of some magnitude.

Unfortunately, a large naval shipbuilding program will do little immediately to improve the U.S. position for two reasons. First, if China desires to maintain an advantage in numbers in the Indo-Pacific, then it has the money, industrial base, and lack of other operational commitments to easily do so.7 Thus, even if the United States decided to double its naval shipbuilding program (a significant challenge given industrial base constraints), China could simply match the new numbers. The second flaw in this argument is time. Quite simply, it takes time to build warships.8 Again, even a doubled shipbuilding budget would yield no appreciable impact on major U.S. combatant vessel numbers over the next five years. Thus, to Admiral Davidson’s point on the threat to Taiwan in the next six years, the naval shipbuilding budget will have little ability to reduce risk over that time horizon. Taken together, it is unlikely a near-term increase in naval shipbuilding would change the risk to U.S. objectives.

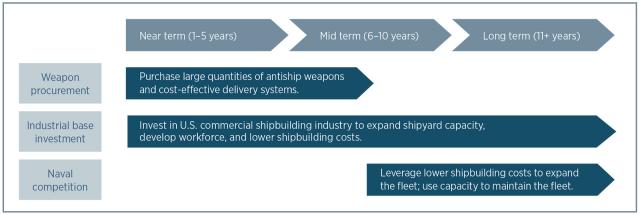

Instead of anchoring on ship numbers and ship building, the United States should pursue a strategy that manages risk in the near term (over the next 5 to 10 years), while developing foundations for an extended maritime competition in the mid to long term (10 to 20 years).

Why a Naval Arms Race Doesn’t Make Sense

The raison d’etre of navies is sea control. As Bernard Brodie wrote in his Layman’s Guide to Naval Strategy, “Sea power has never meant merely warships.” Instead, sea power is the “set of circumstances which enable a nation to control transportation over the seas during wartime.”9 Sea control does not necessarily mean the Navy needs more ships to launch missiles at adversaries or adversary warships. Sea control means ensuring the United States can move cargo ships over the ocean while denying that capability to adversaries.

It is unclear how China’s naval construction program is challenging the U.S. Navy’s ability to exert sea control. Chinese vessels currently are geographically contained within the first island chain. In wartime, U.S. submarines, aircraft, and mines could—with effort—keep the Chinese fleet bottled up within that geography, minimizing the threat to U.S. sea control efforts. Any Chinese ships venturing beyond the first island chain likely would meet a fate such as that of the German East Asia Squadron during World War I or the Admiral Graf Spee during World War II: possibly tactically successful but strategically irrelevant. Practically speaking, allied air power could hunt down and destroy any Chinese vessels outside their protective umbrella.

China likely understands this dynamic.10 As such, the value of its massive growth in surface combatants primarily is for escorting amphibious ships in a Taiwan invasion scenario. In addition, its antiair-capable ships could form part of the integrated air defense network protecting the mainland. Of course, these ships also have peacetime utility—they can exert Chinese influence abroad, although it is unclear if this is cost-effective.

If China’s surface combatants are being built to protect an invasion force, it makes little sense for the U.S. Navy to build more surface ships in response; the Navy is not trying to protect an equivalent invasion force. Similarly, more warships are not necessarily the best tool to stop a Chinese invasion force. If the best counter to ships is torpedoes or guided missiles, it would make more sense to procure the assets capable of best delivering those weapons: submarines, land-based missile systems, and aircraft—not surface ships.

Besides the dubious strategy of building more warships to match China, there is the practical matter: It is near impossible. China produces some 35 percent of the world’s global merchant shipping.11 It has numerous civil-military shipyards and a large and relatively cheap workforce. Merchant ship orders help subsidize the military production cost, further reducing costs to the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). In addition, the majority of Chinese warships are based in the Pacific, while the U.S. Navy deploys all over the world. It is bordering on hubris to think the United States will be able to achieve a numerical advantage over China in China’s backyard.

An Alternative Strategy

The U.S. Navy will be unable to match the PLAN in numbers in the near term, but that is not an overwhelming problem. The United States should instead think about the problem over two separate time horizons: managing near-term risk while developing the foundations for extended competition or conflict.

Reducing Near-Term Risk

Near-term risk reduction through weapon procurement will provide a significant cost advantage to U.S. and allied forces. An Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyer costs approximately $2 billion to build, not including its weapons or operating costs.12 It could be damaged, disabled, or sunk by a range of Chinese antiship cruise missiles or ballistic missiles. Conversely, a Chinese Type 52 or Type 55 destroyer could be disabled or sunk by a U.S. Long-Range Antiship Missile (LRASM) or a Naval Strike Missile costing approximately $2 million. The math for mines and torpedoes is of the same order of magnitude. While delivering these weapons requires costly assets, surface vessels are among the most cost-ineffective options.13

While purchasing weapons is relatively cheap compared with platforms, the United States also must ensure it can deliver those weapons. Here, the United States should focus on three pillars to maximize its weapon-delivery capability: air power, allies, and asymmetric platforms.

The first pillar is air power, described by Colin Gray as, “the sharpest of America’s swords.”14 Air power’s primary benefit is being able to deliver large quantities of weapons over extended time periods. For example, B-1 Lancers can deliver 24 LRASMs at a time. Even assuming a low sortie rate, a single B-1 could quickly surpass a warship’s offensive firepower. The addition of other aircraft, such as other bombers, P-8 Poseidons, and tactical aircraft if in range, would allow air power to deliver punishing blows against an adversary. The United States should ensure it has the quantity of weapons needed to sustain an aerial campaign against adversary shipping and maintain a fleet of aircraft capable of delivering those weapons.

The second pillar is allies. The United States should do everything in its power, including subsidies or other methods if politically and diplomatically acceptable, to encourage Taiwan and other allies to purchase large numbers of antiship weapons. As has been documented, Taiwan’s preference for larger, conventional weapon systems does little to improve its ability to resist a Chinese invasion.15 Instead, Taiwan should acquire more weapons such as the Hsiung Feng III medium-range supersonic missile and its accompanying road-mobile launchers. If the United States is prepared to risk blood and treasure in defense of allies, it is reasonable to expect those allies to pursue rational defense policies.

The third pillar is asymmetric platforms. Here, the Navy should invest in ways to cheaply increase the missile capacity of sea-based assets. Practically, this means exploring the potential to rapidly purchase and convert merchant ships, particularly from the Maritime Security Program, into missile carriers. For example, as T. X. Hammes outlined, containerized munitions could theoretically allow a container vessel to easily fire dozens of antiship missiles.16 In the event of a war warning, conveniently located merchants could be refitted to provide additional firepower at the start of a conflict. This logic roughly mirrors the Air Force’s recent efforts to use transport aircraft such as the C-17 to launch missiles. There are two principal benefits to such an effort: First, it would complicate adversary targeting efforts since any merchant could be a missile carrier; second, it would be cheaper than building warships from scratch.

By purchasing greater quantities of weapons and ensuring both it and its allies have the means to deliver them, the United States could mitigate the near-term risk posed by Chinese capabilities. Such a strategy would be cheaper, timelier, and more effective than an immediate increase in naval shipbuilding or other fleet expansion.

Enhancing Long-Term Competitiveness

Whether the United States builds one, two, or three extra destroyers per year is largely irrelevant to the military balance of power in the 2020s. What will be relevant is the Sea Services’ ability to build, sustain, and repair ships in quantity in the 2030s and beyond.

To prepare the Sea Services for an extended maritime competition, Congress should allocate significant funds toward revitalizing the civilian shipbuilding sector, which not only provides surge capacity in times of rearmament or wartime, but also builds and sustains the Merchant Marine. During World War II, the United States’ shipbuilding sector was able to produce more than 6,000 ships, among them 2,600 Liberty ships.17 Many of those shipyards, so instrumental to winning the war, are now shuttered. If the Navy is unable to build and repair ships in wartime, it will forfeit its chances of meaningfully contributing to victory in any extended conflict.

Practically, a shipbuilding revival will come in the form of subsidies, cargo reservation, and/or tax and financing support.18 This will serve three purposes. First, it will ensure both the workforce and infrastructure needed to support expanded maritime operations are in place. Second, it will expand the Merchant Marine, with commensurate benefits to the U.S. economy, diplomacy, and wartime capacity. Last, and perhaps most important, funding for the civilian maritime sector will help subsidize future naval shipbuilding costs, much as China is able to do for its navy.19

Funding the civilian shipbuilding sector in lieu of naval shipbuilding will require no increase to the Department of Defense’s topline budget, making it more politically palatable. Stimulus for the civilian shipbuilding sector could even be packaged as part of a broader infrastructure or job-creation program, giving it broad appeal across the political spectrum. Civilian merchant vessels also are critical to wartime success. By allocating funding for the civilian shipbuilding sector, Congress can guarantee at least some of the tools necessary for a maritime campaign to exist. Even modest increases to the size and capability of the Merchant Marine would pay significant dividends to the Navy’s fleet.

While investments in the civilian shipbuilding sector will result in little near-term change in the military balance of power, they will have a large effect over the mid to long term. Within a decade, it is possible the Navy could see more shipyards capable of building, maintaining, and repairing ships, and doing so at a lower cost than at present. The resulting industrial base would allow the Navy to compete with PLAN ship numbers outside the first island chain, sustain the resultant numbers, and do so affordably.20 It is an investment in the foundations of maritime power.

Moving Forward

Congress should take several steps to explore this strategy. First, it should require the joint force to submit a cost-optimal, platform and service agnostic, weapon-delivery plan for different contingencies in the Indo-Pacific. This will allow it to make informed tradeoffs on different capabilities. Second, it should solicit an appraisal of shipbuilding and ship sustainment capabilities for this decade to assess how much shipbuilding can, or cannot, change the balance of power. Last, Congress should study options to support and grow the civilian shipbuilding sector.

Fiscal constraints demand the nation spend its defense dollars wisely. While new U.S. warships are needed, even more pressing is the need to increase the number of weapons the joint force can use to deter Chinese aggression or prevail in war. This means focusing on delivering weapons through air power, allies, and asymmetric platforms. Simultaneously, the United States must rebuild the true foundation of maritime power: shipyards and a civilian maritime sector. Over the next decade, a revitalized shipyard infrastructure and civilian maritime sector will enable the Department of the Navy to build new classes of ships and sustain a global maritime competition.

1. Sen. Bernie Sanders, “Washington’s Dangerous New Consensus on China,” Foreign Affairs, 17 June 2021.

2. Elbridge Colby and Jim Mitre, “Why the Pentagon Should Focus on Taiwan,” War on the Rocks, 7 October 2020.

3. Mallory Shelbourne, “Davidson: China Could Try to Take Control of Taiwan In ‘Next Six Years,’” USNI News, 9 March 2021.

4. Defense Budget Overview (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer), May 2021.

5. Heather Venable, “The New Maritime Strategy’s Backward Step,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 6 (June 2021).

6. Megan Eckstein, “Navy’s Spending Plan and a Near-Term China Threat,” Defense News, 15 June 2021.

7. Benjamin Mainardi, “Yes, China Has the World’s Largest Navy. That Matters Less Than You Might Think,” The Diplomat, 7 April 2021.

8. It takes upwards of five years to produce, man, and train a fully functional combatant. “U.S. Navy Guided Missile Destroyers,” Huntington Ingalls.

9. Bernard Brodie, A Layman’s Guide to Naval Strategy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1942).

10. Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2021), V.

11. Matthew Funaiole et al., “China’s Opaque Shipyards Should Raise Red Flags for Foreign Companies,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, 26 February 2021.

12. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, 8 December 2021.

13. This is only magnified when one considers the proportion of VLS tubes that would be occupied by self-defense systems in a high-end conflict and the transit time to reload weapons.

14. Colin Gray, Air Power for Strategic Effect (Maxwell, AL: Air University Press, 2021), 1.

15. Tanner Greer, “Taiwan’s Defense Strategy Doesn’t Make Military Sense,” Foreign Affairs, 17 September 2019.

16. Col T. X. Hammes, USMC (Ret.), “The Navy Needs More Firepower,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 1 (January 2021).

17. “The Emergency Shipbuilding Program,” U.S. Department of Transportation Maritime Division.

18. “U.S. Shipping and Shipbuilding: Trends and Policy Choices” (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, August 1984), 33.

19. Andrew Erickson, “A Guide to China’s Unprecedented Naval Shipbuilding Drive,” The Maritime Executive, 11 February 2021.