Through the din of searing images of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, there were a number of stories that were ultimately proven false.1 Many, such as the reported killing of a CNN journalist who was not a real person, were debunked within 48 hours.2 Even major news outlets were guilty, with many running a debunked graphic claiming the Taliban inherited $83 billion dollars’ of U.S. military hardware.3 While the operation in Afghanistan has been the source of much introspection, there is one crucial and under-discussed factor that the operation laid bare: media literacy.

The term “fake news” is bandied about as the joke du jour, but the implications are anything but funny. Its effects have manifested across multiple conflicts, organizations, and eras. Long before the invasion of Ukraine, Russia regularly targeted NATO forces on deployment in Eastern Europe—most recently in Latvia, where Canadian forces were exposed to COVID-19 disinformation that sowed dissent between military forces and locals and stoked fears at home.4 China employs a vast cohort of disinformation agents to undermine Taiwanese sovereignty and foment positive support for unification.5 While information warfare is not new, its consequences in peacetime have been grave. If the withdrawal from Afghanistan is an indication, fostering media literacy within the U.S. armed forces must become an urgent imperative.

Hacking the Individual

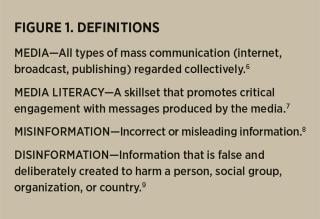

Of the manifold challenges facing the U.S. military, why should the military broadly and service men and women individually care about media literacy? Before exploring the rationale for such a focus, it is important to understand a set of common definitions. (See Figure 1.)

Misinformation, disinformation, and media literacy are fundamentally social technologies: mechanisms and systems of behavior that govern how individuals and groups interact with each other. The impact of false or misleading news stories—especially in the mainstream media—can have outsize effects on military and civilian leaders. To illustrate: In the aftermath of a kinetic strike, false news reports circulate claiming the United States accidentally bombed a hospital. While nothing of the sort may have happened, leaders are now reticent to strike additional targets. The false news reports have muddied the waters, shortening decision-making windows.

This hypothetical scenario sketches the effects of misinformation, but how would this affect the junior and mid-grade officers and junior enlisted and noncommissioned officers that make up the bulk of the military workforce? When the rank and file of the U.S. military have a hard time discerning the reliability of news stories, it can lead them to make inaccurate judgments or, at worst, disobey orders—a wholesale erosion of military discipline. Distrust and discord in the chain of command cut at the heart of military discipline, readiness, and effectiveness.

Action Plans

Effective solutions for combating disinformation in its various forms, including cognitive warfare (weaponized disinformation), on the “supply side” range from the unrealistic (information blackouts during dynamic operations) to anathema to American principles (outright censorship). More hopeful solutions emerge on the “demand side” in the form of large-scale media literacy training for the U.S. military.

Media literacy training is a simple, effective tool to directly combat the malign effects of cognitive warfare and misinformation, and the U.S. military can leverage existing and operative media literacy curricula. The International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) has designed and implemented the Learn to Discern (L2D) program, a half-day, nonpartisan, and publicly available curriculum aimed at arming adult citizens with the tools to be more informed consumers of news.10

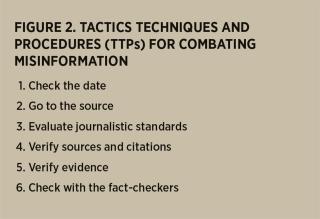

The course has three units: Understanding Media; Misinformation and Manipulation; and Fighting Misinformation. It provides audiences an understanding of the media ecosystem, the types of misinformation and how they play on an individual’s emotions, and effective tools to counter misinformation. The third unit provides users with tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) for combating misinformation. The TTPs range from the more obscure—such as employing reverse photo lookups to check for doctored photos or changes in the direction of shadows in online videos—to the traditional military checklist.11 (See Figure 2.)

The IREX curriculum has proven results. In Ukraine, six months after a single four-hour course, attendees were 28 percent more likely to demonstrate sophisticated knowledge of the news media industry; 25 percent more likely to self-report checking multiple news sources; 13 percent more likely to correctly identify and critically analyze a fake news story; and 4 percent more likely to express a sense of agency over what news sources they can access.12 In Jordan, a similar study reported that participants were 44 percent better able to identify and analyze false or manipulative information; 14 percent possessed a greater sense of control over how they responded to information; and 65 percent maintained a more thorough knowledge about the news media industry.13

The training emphasizes that trusting a media source should not be like a light switch— either “trust or no trust”—but rather a speedometer that goes from 0 to 100, using various barometers to gauge credibility. This should feel familiar to those in the military who have spent time around classified material and intelligence products; most intelligence products have some variation of a confidence assessment associated with them.

The IREX course is just one part of the growing fight against the misinformation ecosystem. Finland has established a vast “multi-pronged, multi-layered” campaign to help its citizens navigate the digital landscape.14 The Finnish government has made fighting misinformation a priority, and it now leads Europe in media literacy.15 In the United States, media literacy is becoming common in elementary school curricula, and the popular Great Courses has partnered with IREX to produce a brief (four-hour) Great Course on media literacy and fighting disinformation. This Great Course is free to all patrons of the Navy MWR library (Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and their families).16

There are a multitude of low-cost, off-the-shelf options the U.S. military can pursue to combat disinformation and misinformation. Preliminary data indicated that the half-day course produced significant results within a population.

Disinformation and misinformation are not going away. Foremost, the military should establish annual online training on media literacy, typically referred to as general military training. In parallel, the services should implement annual media literacy in-person training, encouraging discussion and open dialogue. This requirement would be modeled after the triannual civil rights training requirement for the U.S. Coast Guard, during which third parties are brought in to conduct the training. Next, the services should assemble easily promulgated handouts and leaflets that can be displayed on information boards in major thoroughfares throughout installations.

Finally, military leaders must address the problem head on. Media literacy is analogous to the problem of sexual assault and harassment within the U.S. military, in the sense that it was not a problem until “all of a sudden” it was a glaring black eye. While sexual assault and harassment has not been eliminated from the ranks, the services have made great strides in admitting, combating, and communicating the problem. In 2022, you would be hard pressed to go to any U.S. military command and not see a poster providing the contact information for a service’s sexual assault response coordinator. In addition, annual training and unit-level conversations on the subject abound. While not perfect, recognizing the problem and implementing solutions are first steps.

Great, Another Training!

Most service members would question the need for yet more training. However, training on media literacy is a low-cost, high-yield solution to combating disinformation and misinformation. Training should be centered on educating service members about the risks of misinformation but, more important, should give service members the social technologies and tools they need to succeed. This distinction is important. After all, as Alexander Hamilton once cautioned Revenue Marine officers at the founding of the United States: “Keep in mind that your fellow citizens are free, and, as such are impatient of anything that bears the least mark of a domineering spirit.” While Hamilton was referring to citizens and not military members, the sentiment applies.

When faced with the stark realities of the modern information environment, inclinations to limit or censor information flows have the potential to sow discord. Giving service members agency by providing unbiased, nonpartisan tools to succeed will be met with greater enthusiasm.

Looking Forward

Given combating disinformation’s low cost, ease of procurement, adoption, and adaptation for military purposes, the U.S. military should embark on a multipronged approach to it within the ranks. Robust training, an enhanced cultural awareness, and placing trust in service members’ ability to discern fact from fiction in the modern media environment are all powerful features of a social technology upgrade—a stark necessity in the face of the new global information environment.

1. Kieran Press-Reynolds, “Phony Images of the Taliban’s Takeover of Afghanistan Are Spreading Online from Doctored CNN Broadcasts to Fake Twitter Accounts,” Business Insider, 18 August 2021; Hollie McKay, “Afghanistan Has Its Own Fake News Problem—Special Report,” Deadline, 20 September 2021.

2. The Associated Press, “Not Real News: A Look at What Didn’t Happen This Week,” AP News, 20 August 2021.

3. Dan Evon, “Did U.S. Leave More Than $80B Worth of Equipment to the Taliban?” Snopes, 31 August 2021; and Glenn Kessler, “No, the Taliban Did Not Seize $83 Billion of U.S. Weapons,” MSN, 31 August 2021.

4. Murray Brewster, “Canadian-led NATO Battlegroup in Latvia Targeted by Pandemic Disinformation,” CBC News, 24 May 2020.

5. Dexter Roberts, China’s Disinformation Strategy: Its Dimensions and Future (Washington, DC: The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, December 2020).

6. Oxford Dictionaries, “Media (n).”

7. Monica Bulger and Patrick Davidson, “The Promises, Challenges, and Futures of Media Literacy,” Journal of Media Literacy Education 10, no. 1 (2018).

8. Miriam Webster, “Misinformation (n).”

9. Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan, “Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making,” Council of Europe Report, 27 September 2017.

10. IREX, Learn to Discern: Media Literacy Trainer’s Manual (Washington, DC: IREX, 2020).

11. IREX, Learn to Discern, 100.

12. Erin Murrock, Joy Amulya, Mehri Druckman, and Tetiana Liubyva, “Winning the War on State-Sponsored Propaganda: Results from an Impact Study of a Ukrainian News Media and Information Literacy Program,” Journal of Media Literacy Education 10, no. 2 (2018).

13. IREX, Learn to Discern.

14. Eliza Mackintosh, “Finland is Winning the War on Fake News. What It’s Learned May be Crucial to Western Democracy,” CNN, May 2019.

15. Mackintosh, “Finland is Winning the War on Fake News.”

16. Tara Susman-Peña, Mehri Druckman, and Nina Oduro, “Fighting Misinformation: Digital Media Literacy,” The Great Courses.