I was dead asleep when the boatswain’s mate of the watch knocked sharply on my stateroom door and then opened it.

“XO, Tripoli was just struck by a mine. The CO is on the bridge and we’re making best speed now. A helo is inbound to get you.”

“General quarters. General quarters. Set Mine Condition One,” blared the 1MC.

It was 18 February 1991—during Operation Desert Storm. My ship, the USS Beaufort (ATS-2), had been part of the small amphibious advance force during Operation Desert Shield, preparing the approaches for a naval amphibious landing in Iraq.

As the helicopter approached the USS Tripoli (LPH-10), I could see the massive fuel spill on the unusually flat winter seas. After we landed, a crewmember escorted me through the Tripoli’s crowded bridge to the starboard bridge wing. The commodore and the ship’s captain were both there, glued to their binoculars and watching for other moored mines.

The captain and the damage control assistant briefed me. It was good news. Flooding caused by a single moored contact mine was contained and isolated. “No apparent damage to surrounding area” or “NADSA” on the damage-control plot. To prevent further stress on the watertight boundaries inside the skin, the Tripoli was making bare steerage way, maneuvering under advice from the USS Avenger (MCM-1), which was just off her starboard bow, actively hunting mines ahead.

The Beaufort—the Navy’s largest and most capable submarine rescue and deep-ocean search-and-recovery ship—arrived without any mine hunting assistance, with rescue salvage boarding parties visibly ready on the fantail. Still standing on the bridge wing, I heard over the radio speaker from the Avenger: “Beaufort, I hold you on a mine line with mines close aboard.”

I then noticed several people on the Beaufort’s port bridge wing running to the starboard bridge wing and outside after conn. I saw the rest of the Beaufort’s 112-strong crew—all topside in Mine Condition 1—“sally ship,” or run from the port to starboard side.

“This is Beaufort, roger,” came the reply to the Avenger. “Thrusting starboard to clear a moored mine five feet off our port bridge wing.”

Five feet! That mine—the likes of which just blew a hole in the massive helicopter carrier’s hull, would have sunk the much smaller 3,600-ton Beaufort.

Then, someone ran out of combat and yelled, “The Princeton just hit a mine. There are injuries; she’s DIW [dead in the water].”

With binoculars, we could barely see the USS Princeton’s (CG-59) silhouette, seaward on the horizon made hazy from oil rig fires.

“Commodore,” I heard myself saying, “request permission to detach Beaufort to rescue Princeton.”

“Good idea,” he said, “sounds like she’s in rough shape.”

There was so much happening on the Tripoli’s bridge that no one noticed when I went up to the primary task force circuit on a stanchion in the center, grabbed the handset, called the Beaufort, and tasked her to proceed to the Princeton to render assistance.

I then told the commodore I was proceeding to primary flight control to get a helo to the Princeton to conduct a preliminary rescue assessment in advance of the Beaufort’s arrival.

Next came the experience that resulted in one of the most vivid memories of my life. I hadn’t walked 30 steps from the captain’s chair when a thought—a blinding flash of the obvious—turned me around.

“Commodore,” I said, “Request permission to also detach Adroit to lead Beaufort through to the Princeton.”

Until that point, no one in the advance force had even mentioned the notion of lead-throughs; I hadn’t seen the idea anywhere in writing.

“Yeah,” the commodore replied. “Great idea. Permission granted.”

So, I went back into the pilothouse and picked up the radio-telephone handset and detached the USS Adroit (MSO-509) to lead the Beaufort through to the Princeton.

Less than five minutes later, I was airborne to the Princeton. As we would learn, the Princeton had detonated an Italian-made Manta bottom-influence mine just off her port quarter, which lifted the stern out of the water. The blast wave and the additional hull pressure forward then triggered a second mine off her starboard bow. Two cheap little mines had removed this $2 billion national asset—the Persian Gulf’s primary threat-sector antiair warfare ship—from the fight. It was now a useless piece of iron, and the amphibious advance force no longer had the protection it once had.

As if the Princeton were a ghost ship, no one on board greeted the Tripoli’s landed helo on the flight deck. It just sat down and I climbed out, with my backpack full of all my ship salvage engineering books. I made my way to damage control central, getting wet along the way. The fire main was broken and leaking everywhere, with standing water in the passageways. The first mine apparently broke the ship near the fantail, which was moving eerily in the light swell. Fortunately, there was no other hull damage.

The big surprise was that it took about five hours for the Adroit and Beaufort to go the 12 miles to the Princeton because—unknown to any of us—there were dozens of mines in their path that had to be dodged. The Beaufort launched its rigid-hull inflatable boat (RHIB) with a dive team to speed over the top of the mines and begin the initial hull survey. As I watched the RHIB make way—laden with sets of scuba doubles and four divers—the dive team got visibly excited and pointed in the small boat’s wake. When the dive team arrived alongside, they explained how the boat had plowed directly over a moored mine, just missing the propeller.

The Beaufort finally arrived and backed down under the broken ship’s prow—just under her anchors—and passed the messenger. But the Princeton’s crew were traumatized and emotionally exhausted. It took them five hours to make the simplest connection of their anchor chain to the Beaufort’s tow pendant.

At dusk, the Beaufort began to make turns in the Adroit’s wake toward Jebel Ali and the rendezvous point with the commercial salvage ship that would take the Princeton to the waiting dry dock.

That night was a nightmare shared by the captains and crews of all three ships. There were so many mines that the Adroit expended all her equipage flares in the tow path and resorted to using little floats laced with chem-lights so the Beaufort, with the Princeton in tow, could maneuver away from the mines in the dark.

The next day, the Beaufort transferred the Princeton to the commercial salvage ship and turned back to Iraq’s nearshore waters to do the underwater hull survey on board the Tripoli. That hull survey had to wait. When we arrived, the seas were almost 12 feet again, and the Tripoli had to keep her bow down to prevent bursting her watertight integrity.

We were lucky in two ways. First, had the Princeton not been towed during the calm weather, she might have lost her entire stern section and had progressive flooding at the stern tubes. Second, as the Beaufort’s underwater hull survey of the Tripoli showed when the swells finally calmed, the mine had blown a 20-foot-diameter hole in the big ship’s hull. Had the mine made contact instead at the main engine room, the Tripoli might be a Persian Gulf tourist diving attraction today.

Lessons Learned for Today’s New Cold Wars

The effective naval mine soft kills on the Princeton and Tripoli took place during a tiny conflict in which the capabilities of the adversary were minimal and the United States quickly gained control of the air and sea battlespace. Yet, there seem to be two lessons for the prospects of larger conflicts with more capable adversaries.

Lesson #1: Plan on Mines

(Where You Do Not Expect Them)

A more capable adversary such as Iran, Russia, or China—an axis that performs naval exercises together—will use mines for defense and deterrence, and it will put them exactly where the U.S. Navy needs to operate, based on U.S. weapon systems capabilities and objectives it wants to deny.

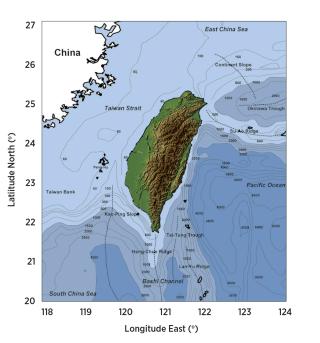

If China decides to invade or blockade Taiwan, it could mine the approaches to Taiwan’s ports to weaken and coerce the country, and mine the edge of continental shelf gaps between the Ryuku Islands to the north and the Taiwan Bank to the south as a form of defense-in-depth in what it claims as its own territorial waters. The bathymetric data for the Taiwan Strait and the ridge between the rest of the Ryukus suggests these choke points might be sufficiently mined to deter submarines and ships from a U.S.-led coalition from getting too close. Area denial such as this will force all access to Taiwan to the deep-ocean west side, where only one of the island nation’s seven ports is located. Because of global dependence on Taiwan’s semiconductors, such mining would severely threaten the global supply chain and thus also function as a form of nonnuclear strategic deterrence. Experts at the Naval War College believe “the employment of sea mines remains a core tenet of Chinese naval war-fighting doctrine.”1

Just-in-time rapid saturation of a these choke points and key-objective approaches would be easy for a great power operating in its own territorial waters on the continental shelf’s littorals. A study from China’s National Defense University envisions a two-phase Chinese mine blockade—the first four to six days laying 5,000–7,000 sea mines; the second laying another 7,000 mines.2 That is potentially 14,000 mines in just over one week.

The Strait of Hormuz is in Iran’s territorial waters, and the mere threat of its mining is a form of strategic deterrence given how much of the world’s oil still transits this strait every day. In 2012, Iran boasted upward of 6,000 mines, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.3 A decade later, given its impressive progress in building stealth drones and precision-guided long-range cruise missiles and satellites, it is not hard to imagine that its mine stock has grown and become more lethal. And Russia’s and China’s capability must be orders of magnitude higher than Iran’s.

The mines laid by near-peer adversaries in their claimed territorial waters also are more sophisticated than those that achieved easy soft kills on the Tripoli and Princeton three decades ago. The Iranian Navy and Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) have larger and sophisticated arsenals, with mines much harder to counter and more mobile—the kind that passively listen and launch when certain parameters are met. In 2014, the PLAN Dalian Naval Academy published a “Feasibility Study on Laser Guided Technology for Water-exit Attack Mine.” Instead of launching a captured torpedo, this new naval “mine” quietly surfaces and launches an antiship missile at close range.4

Lesson #2. Do Not Plan on Clearing Mines Until You Have Decisively Won the War

The second lesson is that demining is either ineffective or impractical until hostilities have ceased.

First, it is ineffective, because cleared lanes can be quickly remined with fishing boats, small swarming boats, quiet electric submarines, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and low-cost drones. And, once a shipping lane has been cleared, the adversary can deploy its smartest mines (e.g. captured torpedoes or surfacing missiles) with more effectiveness, since that cleared sea lane is the path the United States intends to use.

Second, it is impractical, even with the latest generation of gear assisted by artificial intelligence, because it takes far too long to clear a meaningful number of sophisticated mines that a near-peer adversary protecting its littorals would lay or re-lay. During this time, the United States would need both air and sea control—not just superiority. Recall from the first lesson that U.S. forces should plan on having to clear thousands of newer mines in critical choke points and approaches. Yet, it can take up to a whole day for a mine hunter to clear a single mine, depending on the surface conditions, bottom type, depth, current, crew, reliability of the ship’s intricate systems, and threat condition.

The Beaufort, at only 3,600 tons, often functioned as a mother ship for larger minesweepers and mine countermeasures ships in the Gulf War; I remember watching these craft-sized ships bob like corks next to us. In the area of logistics and proficiency, they carry few spare parts and are led by inexperienced junior commanding officers and small wardrooms of junior officers—none of whom are subject matter experts or possess any real mine clearing experience.

Much of the Navy’s mine-hunting and clearing technologies are 1980s vintage and have serious difficulty finding and identifying heavy bottom mines that sink partially or fully beneath the mud, especially when the sea state is high. Yet, these are often the conditions in the entrance to ocean-facing ports with their topography carved by rivers.

Technology will not be a panacea, since ultimately there is no such thing as an unmanned system; all new-generation ROVs require major capital ships nearby under the cover of a fleet of other forces that maintains air and sea superiority and control. That is not possible in a conflict in claimed territorial waters of near-peer adversaries with swarming capabilities.

Based on these two lessons, it seems foolish to plan on naval combat in a near-peer adversary’s littorals. The oldest and cheapest form of deterrent and area denial of naval forces renders such planning unwise. We might conclude with a twist on Admiral David Farragut’s famous words about the mines in the 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War: “Damn! . . . The Torpedoes!”

1. Lyle J. Goldstein, “China Thinks the United States Can’t Handle Sea Mines,” National Interest, 14 October 2021.

2. Goldstein, “China Thinks the United States Can’t Handle Sea Mines.”

3. Anthony H. Cordesman, Alexander Wilner, Michael Gibbs, and Scott Modell, U.S.-Iranian Competition: The Gulf Military Balance–1: The Conventional and Asymmetric Dimensions (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2012).

4. Goldstein, “China Thinks the United States Can’t Handle Sea Mines.”