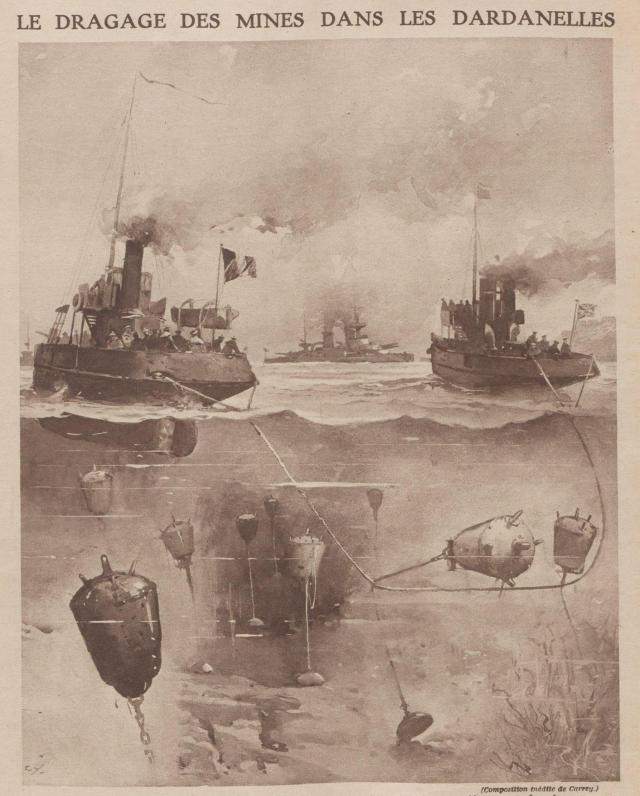

In a bid to decisively end World War I, the Royal Navy pushed the Dardanelles Strait with a combined naval task force of the Triple Entente powers, consisting of French, British, and Russian warships. Recognizing a critical vulnerability and fearful of an invasion, the Ottoman Empire defensively laid 393 mines in ten rows. In preparation for an eventual assault, Entente forces initially attempted to use minesweeping trawlers travelling at one to four knots to clear the mines during the day. However, shore-based gunfire forced minesweeping efforts to be conducted at night.

The geography of the narrows forced minesweeping efforts so close to the shoreline that high-power searchlights illuminated the minesweepers while shore artillery fired against the slowly retreating vessels. This steady opposition rendered the entire nearly two-week effort ineffective. The day before the ill-fated attack, reconnaissance seaplanes failed to spot the mines laid by the small Ottoman minelayer Nusret in an assumed mine-free area. On the day of the attack, 18 March 1915, minesweeping trawlers discovered and destroyed three mines in the same area thought to be clear before the trawlers were forced to withdraw under fire, failing to relay the information to the rest of the task force.

Ultimately, the failure of minesweeping efforts culminated in the loss of three Entente ships to a line of 20 naval mines laid by the Nusret in the Dardanelles Strait. The undetected naval mines at Gallipoli sank the HMS Irresistible, the French battleship Bouvet, and badly damaged the battle cruiser HMS Inflexible. This led to the withdrawal of the Entente naval task force and the conclusion that the Dardanelles Strait could only be taken with the assistance of land forces, resulting in the ill-fated and tragic ANZAC landings at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915.

If the 20 mines thwarted an entire naval force, what could the 100,000 naval mines currently in Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) inventory do to undermine sea control? For starters, well-placed minefields in the eastern approaches to the Taiwan Strait, Luzon Strait, and other critical chokepoints could exclude, canalize, and delay U.S. and allied naval forces, granting Chinese forces local sea control for an invasion of Taiwan.

The Assassin’s Mace

The naval mining of Gallipoli is a textbook case of what sea denial through mining can achieve. While China has expanded its submarine fleet and advanced-missile capabilities, it has also been developing less attention-grabbing mine warfare capabilities with equal fervor. Referred to as an “Assassin’s Mace” capability, Chinese mine warfare is focused on countering widespread U.S. maritime dominance through sea denial at specific times and in specific areas. The asymmetric capability of maritime mines is best captured by a roughly translated Chinese maxim of “Four Ounces Can Move One Thousand Pounds,” a key point for Chinese naval strategists. They note that the mere suspicion that minefields might be present is enough to disrupt battle plans, close sea lanes of communication, and force the rerouting of personnel, weapons, and supplies.

Iran and Iraq demonstrated the willingness to use minefields as attractive asymmetric counters for smaller nation states. Iran attempted to shut down maritime traffic in the Persian Gulf by denying sea lanes using maritime mines during the Iran-Iraq war in what became known as the Tanker Wars. This prompted a robust U.S. military response and convoy escort operations to protect shipping during the 1980s. In April 1988, one undetected mine laid by an Iranian minelayer more than a year earlier struck and nearly sunk the USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58), costing $90 million in repairs. Two years later, two Iraqi mines struck the USS Tripoli (LPH-10) and USS Princeton (CG-59) during the first Gulf War, causing $21.6 million ($43 million when accounting for inflation) in damage. By comparison, the two naval mines that caused the damage cost approximately $10,000 for one and $1,500 for the other. The detrimental psychological effect of minefields is demonstrated by Marine Corps Major General Tracy King’s explanation, “You only need one mine to make a minefield. And I’ve been in a minefield, it’s frickin’ scary.”

Chinese strategists also use North Korea’s 1950 mining operation at Wonsan to highlight the effectiveness of mining. North Korea laid three thousand mines, denying the U.S. Navy access to Wonsan Harbor. Allied forces swept and destroyed only 225 of these mines and suffered heavy losses, including four U.S. minesweepers, one fleet tugboat, and five severely damaged destroyers. As with Gallipoli, the minefields were laid within range of shore batteries and once the minesweepers were sunk, the batteries turned their fire on the survivors in the water. The day after Operation Wonsan commenced, the commander of the naval task force, Rear Admiral Allan Smith, delivered a message , “We have lost control of the seas to a nation without a Navy, using pre–World War I weapons, laid by vessels that were utilized at the time of the birth of Christ.” Of note is the fact that most sea mines laid worldwide since 1950 have been by merchant ships, fishing trawlers, or junks. China’s maritime militia, which leverages civilian merchant ships and fishing trawlers, has an estimated 17,000 of these vessels available.

Not Enough

The failure of the 35 minesweepers in the four-mile-wide Dardanelles Strait underscores that mine clearance takes time and assets. Although the Navy will procure a total of 35 littoral combat ships (LCSs)—Independence and Freedom variants—for some $600 million each, only eight will routinely carry the mine countermeasure (MCM) module, hardly an affordable and plentiful asset for a vital mission. To address this lack of mine countermeasure hulls, Major General King has recommended expeditionary sea bases (ESBs) as better mine hunting platforms because of their larger mission bay and survivability. However, Gallipoli and Wonsan demonstrated how even short-range artillery can disrupt mine countermeasure operations. Modern antiship cruise missiles could do far worse.

Unmanned Low-Profile Vessels

Although the catastrophic naval blunder at Gallipoli happened more than a century ago, it still raises the question of what would have happened if the minesweepers were successful. Just like Gallipoli and Wonsan, a contested littoral environment will have no shortage of enemy sensor and attack networks. If Gallipoli and Wonsan taught anything, it is that the enemy will not sit idly by during mine clearance operations.

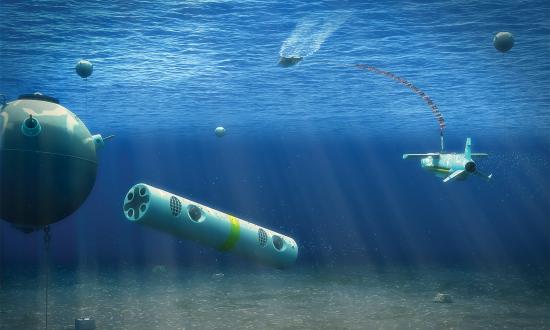

Countermine warfare is slow, tedious, and dangerous. Recently, two related proposals for covert scout and covert logistics vessels, both inspired by so-called narco-subs, have emerged as solutions to stage sensors and supplies deep inside contested environments where enemy forces could easily neutralize conventional scouting and logistics vessels. These covert and expendable unmanned, low-profile vessels (LPVs), with composite hulls and decks awash, could creep through suspected minefields, minimizing the chances of a naval mine striking because of wake, noise, or magnetic influence. By creating a collaborative picket line of sonar-equipped autonomous or remotely operated low-profile mine hunting vessels, littorals and sea lanes of communication could be cleared well ahead of the amphibious group, task force, or convoyed shipping. Enemy sensors would have great difficulty in detecting and targeting a composite vessel with minimal freeboard. Autonomous LPVs promise to perform high-risk mine countermeasure operations within enemy weapon-engagement zones and minefields without risking human life or expensive surface combatants.

Autonomous or remotely operated LPVs can be programmed for the various rapid mine hunting formations required. If one vessel is sunk, the search pattern and formations could be changed remotely or autonomously to ensure the optimal formation for route clearance.

Send in the Marines

At Gallipoli, the one-to-four knot speed of minesweeping operations resulted in two sunken and several damaged minesweepers and led to the ultimate withdrawal of naval forces. To combat the notoriously slow nature of countermine warfare, Northrop Grumman developed the AQS-24 Mine Hunting System. Originally towed behind MH-53 Sea Dragon helicopters, the mine countermeasure system has demonstrated operational effectiveness towed behind an LCS-based unmanned surface vessel (USV). The system is capable of mapping underwater topography at 18 knots, a far cry from the four-knot maximum at Gallipoli.

As the Marine Corps looks to acquire long-range unmanned surface vessels (LRUSVs), the service is well positioned to enter the counter-mine warfare mission. By equipping systems like the AQS-24 to LRUSVs, Marines can help clear mined waterways. Marines stationed in key maritime terrain (i.e., choke points and narrow seas) will be crucial in maintaining open sea lanes. Using LRUSVs paired with AQS-24 systems can ensure wide-ranging coverage at speed. Also, AQS-24 system outputs could be paired with machine learning to correctly identify and classify anomalies or mines. While the LRUSVs will be capable of full autonomy, they may be optionally manned to adjust the payloads and search patterns for the various environments that may be encountered.

In addition, LRUSVs could be equipped with a towed airborne launch of naval systems (TALONS) parasail to extend line-of-sight and sensor range, allowing vessels to scan the path ahead for mines near or on the surface. During the battle of Gallipoli, minesweepers found mines in an area that was previously thought to be clear but did not relay the information to the attacking naval force. LRUSVs networked together can leverage TALONS-mounted electro-optical/infrared sensors, including water-penetrating light detection and ranging (LIDAR), to provide real-time awareness of surface and submerged threats.

Leveraging Organic Acoustics

Even considering the proposals above, the lack of assets for mine countermeasures demands novel solutions. To assist with the quantity of sensors and assets the Indo-Pacific theater demands, Mother Nature provides a unique opportunity to avoid a 21st-century Gallipoli. Ask any sonar operator about whether they hear the sound of bacon frying while searching for submarines and they will all answer with a resounding, yes! The sound of frying bacon is generated from snapping or pistol shrimp. When the shrimp closes their one enlarged claw, it creates a cavitation bubble that then collapses, producing noise up to 210 db. In World War II, U.S. submariners evaded Japanese hydrophones by hiding in snapping shrimp colonies to mask their acoustic signature.

Recently, researchers have shown that snapping shrimp can also be used for locating submerged objects. By using a Remotely Operated Mobile Ambient Noise Imaging Systems (ROMANIS), Singaporean researchers sponsored by the Office of Naval Research have detected silent submerged objects through only ambient noise.1 The researchers demonstrated that passive ranging of silent submerged objects is possible using the returns from noise produced from snapping shrimp, analogous to range estimation using multistatic sonar.2 Despite the success of ROMANIS, the array for the experiment only used 508 sensors. A fully populated array will require more than ten thousand sensors and far more computing power.3

However, ROMANIS provides promise, especially in the shallow and warm waters of the East and South China Seas where the snapping shrimp activity is increasing because of rising sea temperatures. Pairing ROMANIS or similar systems with future unmanned underwater vehicles, or using it as standalone sensing unit integrated into DARPA’s Ocean of Things, ROMANIS can help lift the fog of war that envelopes sea denial by mine warfare.

The World War I minesweepers’ inability to clear the Dardanelles Strait resulted in the loss and withdrawal of the Entente fleet at Gallipoli and led to the ill-fated amphibious landings at Anzac cove. Beyond sea denial, mines have sunk more U.S. warships since World War II than missiles, guns, and bombs combined, highlighting the ever-present need to counter this critical threat. While LCSs contribute to the overall number of Navy MCM ships, there are not enough dedicated mine countermeasure assets to cover the vast expanses of the Indo-Pacific theater. Unmanned low-profile vessels, Marine Corps integration in the counter-mine warfare mission, and technologies that allow for a biological multistatic sonar system promise a multipronged mine countermeasures approach that will ensure safe and secure sea lanes of communications. Relying on a single service, platform, or tactic for such a crucial mission is destined for failure and to become a 21st-century Gallipoli.

- Too Yuen Min, “Passive Sensing with Snapping Shrimp: A Thesis Submitted for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy,” National University of Singapore (2016), 15.

- Too Yuen Min, “Passive Sensing with Snapping Shrimp,” 16.

- Too Yuen Min, 23.