John B. Hattendorf, Professor Emeritus of the U.S. Naval War College, offers what—at first blush—appears to be a straightforward, static definition of maritime strategy, “. . . the direction of all aspects of national power that relate to a nation’s interests at sea.” In making this statement, Hattendorf recognizes that an important characteristic of such a strategy is that those interests and the international environment in which they are developed are not static. Writing about the period of the twentieth century World Wars, Hattendorf states:

The period leading up to WWI was quite different from ours. It was a world of imperial rivalry and colonial expansion, a time of rising military and naval budgets, and a period in which regional tensions in Europe had immediate and world-wide impact. Similarly, the period leading up to WWII, a time of unresolved issues left from WWI, was equally different from ours.

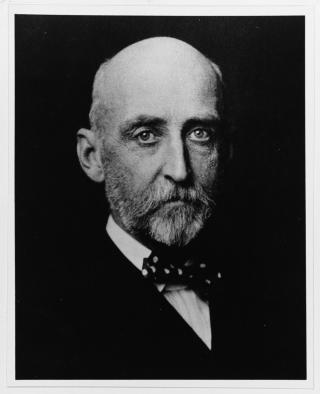

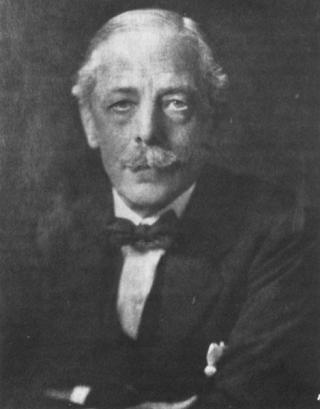

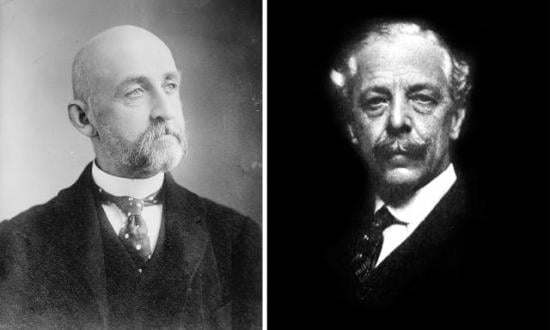

However, books and writings are static, reflecting the conditions present at the moment of publication. This leads us to the question: Are maritime strategic thinkers such as Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan and Sir Julian Corbett as relevant today as when they first put pen to paper during the period leading up to the First World War (WWI)? Arguably no, because the international environment has evolved while the authors’ strategic concepts have remained static products of their time.

Mahan and Corbett in the International Relations Framework

How well Mahan and Corbett fit into the international relations (IR) framework is critical to understanding the key to their modern-day relevance as maritime strategists. The IR framework is comprised of models portraying various international and foreign policy perspectives. Citing the faculty of the Department of International Relations of Norwich University, such models include:

- Realism: “. . . a straightforward approach to international relations, stating that all nations are working to increase their own power, and those countries that manage to horde power most efficiently will thrive, as they can easily eclipse the achievements of less powerful nations. The theory further states that a nation’s foremost interest should be self-preservation and that continually gaining power should always be a social, economic, and political imperative.”

- Liberalism: “. . . based on the belief that the current global system is capable of engendering a peaceful world order. Rather than relying on direct force, such as military action, liberalism places an emphasis on international cooperation as a means of furthering each nation’s respective interests.”

- Marxism: “. . . posited that societies could escape the self-destructive nature of capitalist socioeconomic systems by implementing socialist theory into their policies, both locally and abroad.”

Using the IR framework to analyze Mahan and Corbett’s time, it becomes clear that realism was the dominant model of the period leading up to and during WWI. The great powers of Europe, the United States, and Japan were engaged in a struggle for control of territory and resources at the expense of their rivals. There were no international organizations comparable to the United Nations to monitor and arbitrate disputes. Alliances were fluid, as exemplified by events such as the Fashoda Crisis (1898), in which the United Kingdom and the Republic of France nearly went to war only a few years before forming the entente that would lead to their unshakeable alliance in WWI. It was not until that war that the great powers would recognize that such alliances were essential not only for national survival but as a check on unrestrained violence and destruction.

However, Mahan and Corbett could only understand their world as it was—one in which realism defined international relations. Thus, they advocated for the construction of powerful fleets of surface gunships that would assemble sufficient combat power to compete for maritime superiority. In their day, this was a logical strategy. Unfortunately, Mahan’s and Corbett’s vision of maritime superiority has failed to adapt to a changing international environment—thus obscuring viable alternatives from their successors that were both less costly and, arguably, more effective.

The Changing Strategic Environment and the Jeune Ecole

The Jeune Ecole (Young School) strategy has always had a dubious reputation as the poor nation’s alternative to building a powerful battle force like the early twentieth century British Royal Navy. Developed in France (hardly a poor nation), which lacked the maritime infrastructure to build a powerful rival battlefleet, the strategy called for construction of inexpensive but fast small ships armed with unconventional weapons—such as the torpedo—to which the British battleships were vulnerable. The goal was not to destroy the British fleet but rather to weaken it while disrupting British seaborne commerce to the point that British maritime superiority was threatened, and they would sue for peace. The greatest flaw in this strategy, however, was that the attacking small craft could still be seen and targeted by the battleships and their escorting destroyers and therefore had difficulty getting close enough to their targets to effectively attack. The battleship or their destroyer-escorts could still defeat them.

Meanwhile, WWI wrought a profound change in the global strategic environment that would ultimately transform the character of international relations. The warring great powers realized they were too evenly matched to achieve their realist objectives. National survival became the only objective that really mattered. This led them to consider ways of fighting that would have been unheard of before the war.

One tool in the evolution of new warfare methods was the diesel-electric submarine. Even the “father of the dreadnought battleship,” Admiral Sir John Fisher, recognized the value of the submarine as a cost-effective “stealth” weapon against a vulnerable battlefleet and its nation’s vital seaborne commerce. For economic as much as for military reasons, Fisher strongly advocated cessation of battleship construction in favor of submarines to be used offensively against enemy battlefleets.1 It was Germany, however, which took submarine employment one step further by using it to establish a blockade in which targets would be sunk without warning. The German Unterseeboots (U-boats) devastated British commercial shipping, confounded the leaders of the Royal Navy, and brought Great Britain close to defeat. Once the attacker possessed a stealth capability, the proponents of the Jeune Ecole witnessed the realization of their vision—one that might revolutionize naval warfare.

At the conclusion of the war, a number of U.S. Navy admirals certainly thought the revolution had arrived. These included Admiral William S. Sims, Commander of U.S. Naval Forces in Europe; Rear Admiral William V. Pratt, Assistant Chief of Naval Operations; and Rear Admiral Harris Lanning, an experienced destroyer flotilla commander and later president of the Naval War College. All three publicly advocated for a paradigm shift to a focus on submarine warfare over the battlefleet.

This shift marked the beginning of what Harold and Margaret Sprout called a new order of sea power which developed as a subtext to a dramatic shift in international relations away from realism to a more fragmented environment in which some nations embraced liberalism, others embraced Marxism, and still others embraced a more virulent form of realism.2 The 1920s, for example, saw liberalism briefly triumphant with the formation of the League of Nations and signature of the Washington Naval (Arms Limitation) Treaty in 1922. By 1930, however, some nations left destitute by the Great Depression fell back on their natural inclination and re-embraced realism and a traditional maritime strategy. Notable among these were the future Axis powers: Germany, Italy, and Japan. Nations with liberal inclinations, such as Great Britain and the United States (including the three admirals discussed above) also reembraced the traditional maritime strategy in response. Once again, capital ships (battleships and the new aircraft carriers) became the arbiters of sea power.

Nevertheless, the Second World War (WWII) became an ideological conflict pitting liberalism and Marxism (the Soviet Union) against realism. This was a vastly different strategic environment than the one Mahan and Corbett worked in. One assumption ripe for change was that the teachings of the Jeune Ecole were flawed and virtually useless. This assumption was called into question by the German submarine campaign of 1917-1918 against the United Kingdom and validated when that campaign was renewed in 1939. In the latter phase, Germany not only came to devote all its naval resources to development and construction of U-boats but one of the Allied powers devoted all its naval resources to antisubmarine warfare. From scratch, Canada created the third largest fleet in the world by 1945; a fleet of light aircraft carriers, destroyers, frigates, and corvettes devoted entirely to fighting U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic.3

In two World Wars, Germany demonstrated the offensive potential of Jeune Ecole theories while Canada and the Royal Canadian Navy demonstrated their defensive potential. These were lessons learned by the Soviet Navy after WWII as that nation focused its efforts on constructing hundreds of submarines to attack North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) naval forces and commercial shipping. While the United States and NATO could afford to respond to this challenge, the U.S. Navy remained wedded to Mahan’s and Corbett’s visions and expended vast resources to maintain a modern version of the capital ship fleet that was more appropriate to the realism of American international relations in their day and not the liberalism the United States claims to embrace today.

Inaccessibility

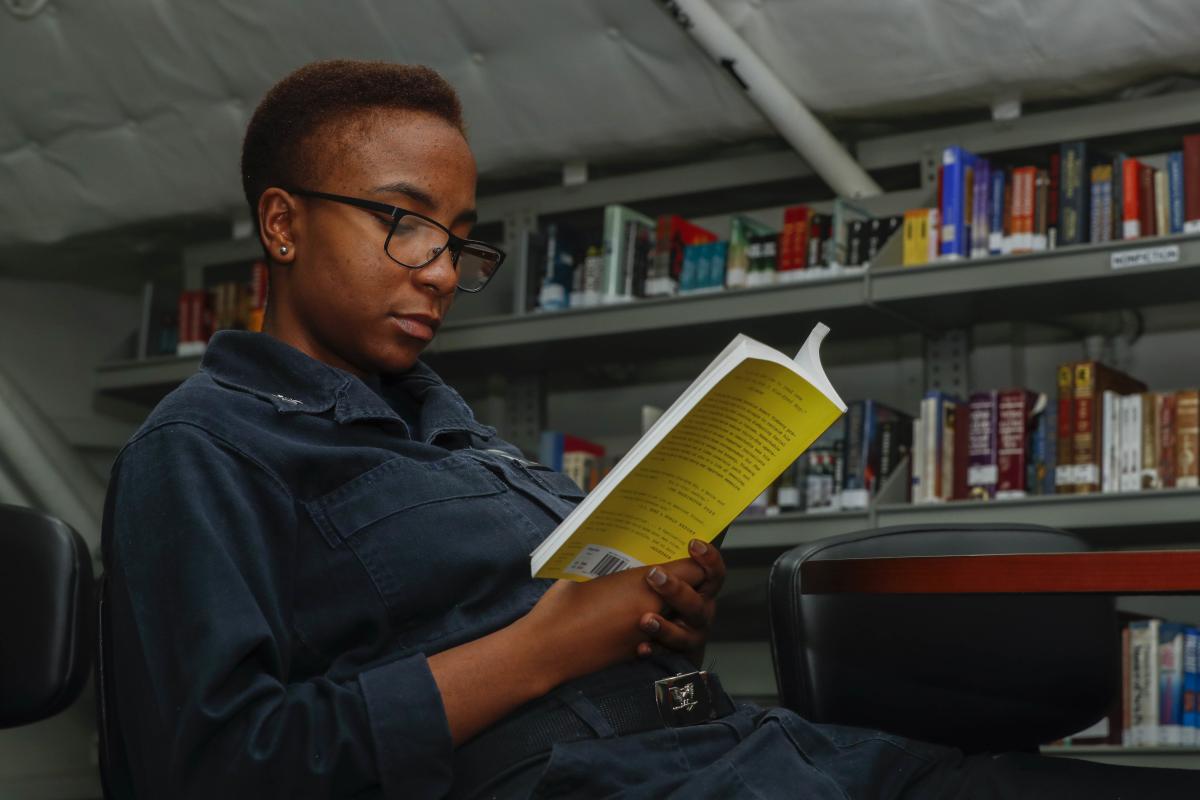

One of the least commented upon difficulties with Mahan and Corbett today is that no one beyond scholars reads their works. Mahan, for example, wrote for senior makers of naval policy in the U.S. government and for mid- and senior-grade U.S. naval officers who were moving into command-level leadership. Reading Mahan, however, was so burdensome and time-consuming that his works were distilled into easy-to-read summaries by the early 1920s that Naval War College students used in their strategy courses.5 Meanwhile, policy-makers and interested citizens were likely to read more easily digestible books, such as Harold and Margaret Sprout’s The Rise of American Naval Power, 1775-1918, rather than grapple with Mahan’s Victorian-era prose.4 Mahan’s works may have been to staff college strategy departments what James Joyce’s Ulysses is to university English departments—often cited but seldom read.

Corbett’s texts were much more approachable but, in both cases, neither staff college students nor senior policymakers were afforded enough time in their busy professional lives to make the kind of study of Mahan’s or Corbett’s works that would permit them to formulate their own conclusions. Instead, they relied on popular texts or on academically prepared summaries that often reflected the approved “schoolhouse” solution rather than an objective one.6 This is likely as true today as it was a century ago.

Questioning Mahan and Corbett

Early nineteenth century sea power theories may have remained static, but historiography has not. Modern scholars have a deeper understanding of the history of the 1660-1815 period than they did in Mahan’s and Corbett’s day. They also possess a robust international framework from which to conduct analysis of the international situation as it exists today and how it differs from that of Mahan’s and Corbett’s time. The time has come to develop a new set of theories that are accessible and founded on our current understanding of history and international relations. These new theories will help guide us to developing a maritime strategy and an appropriate fleet to execute it that will best respond to the maritime challenges we face today.

- James Goldrick, “Review of Lambert, Nicholas. Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1999.”

- Harold and Margaret Sprout, Toward a New Order of Sea Power: American Naval Policy and the World Scene, 1918-22 (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1940).

- W.A.B. Douglas, Roger Sarty, and Michael Whitby, The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy, Vol. 2 (St. Catherine’s, Ontario, Vanwell Publishing, 2006).

- An example of such a summary is H. L. Pence, Head, Department of Intelligence, U.S. Naval War College, “Outline to Accompany Presentations of Naval and Military History, 1492-1917,” Record Group 4, Box 215, Naval Historical Collection, Naval War College Archives.

- Harold and Margaret Sprout, The Rise of American Naval Power, 1775-1918 (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1939). The Sprouts wrote a follow-on book, Toward a New Order of Sea Power, 1918-1922, in which they argue that the strategic environment described by Mahan had been fundamentally changed by the emergence of non-European sea powers to the extent that his sea power thesis was no longer as relevant.

- The Naval Historical Collection in the Naval War College Archives has numerous examples of faculty-prepared summaries derived from Mahan’s work that were used by student working groups to conduct case study analysis of naval conflicts from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries.