There is an emerging crisis in the Pacific, fueled by the war on fish. Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing “erodes both regional and national security, undermines maritime rules-based order, jeopardizes food access and availability, and destroys legitimate economies.”1 The most deleterious effects are on vulnerable coastal states without sufficient resources to police their territorial waters. To counter this threat, the United States should expand Coast Guard presence and foster a cooperative maritime strategy with nation-states less able to defend themselves or their resources. It must leverage the unique capabilities of the Coast Guard and provide a deliverable force package to combatant commanders around the world. Agile Maritime Enforcement Groups (MEGs) are needed to deploy across the globe.

The Great Fish War

Fish is one of the most consumed foods in the world; nearly 200 million metric tons were produced and consumed globally in 2019.In the face of rising demand, the percentage of globally overexploited fish populations has tripled since the 1970s, with some populations experiencing 75 percent declines.2 This is a national security threat for every country in the world.

The country that poses the most serious threat to vulnerable marine resources is also the one with the greatest dependence on them: China. China is a massive consumer of fish, but it also is the leading exporter.3 Through decades of exploitation and overfishing, it has decimated major sections of its marine ecosystem.4 A 6,800-mile seawall constructed along 60 percent of its coastline for aquaculture and industry development has resulted in a 50 percent loss of its coastal wetlands and mangroves, as well as an 80 percent loss of coral reefs, which are crucial for the spawning and growth of numerous fish species.5

Now faced with sparse prospects for local wild fish, China spends billions of dollars annually to subsidize its deep-water (i.e., distant-water) fishing fleet, which comprises more than 3,400 large, oceangoing ships (some estimates are as high as 17,000).6 Approximately 2,500 of these distant-water vessels operate in the East China Sea, including within the exclusive economic zones (EEZs)of Japan and South Korea, and nearly 1,000 operate in regions far from the Chinese homeland. These ships are large. In a matter of weeks, they can harvest more wild fish than a local industry could harvest in a year. They are deployed in swarms—armadas of hundreds of refrigerated ships and boats with the sole aim to ambush and clear the ocean of life.

Collectively, West Africa, South America, the South China Sea, and widespread regions in the Indo-Pacific bear the burden of such offshore vessels. The evidence of incursions is overwhelming: Ecuador sentenced dozens of Chinese fishermen to jail in 2017 for illegal fishing in the Galapagos, the Argentine Coast Guard sank a Chinese vessel fishing in its territorial waters in 2016, and in 2019, Indonesia sank 51 confiscated fishing boats from various nations caught poaching its waters, to name just a few of many documented cases.7

Environmentally, the biggest threat is to numerous highly migratory species, including tuna (bluefin, yellowfin, albacore, blackfin, skipjack, bullet), pomfret, and swordfish. While these species are valuable economically and often targeted by illegal fleets, they also are a key segment of the global marine ecosystem. Recent studies estimate their numbers have declined by nearly 50 percent since the 1970s, and possibly much more.8 Overfishing, regardless of the location or ocean, results in reduced spawning and, therefore, lower future fish populations, which has devastating effects for any country that hopes to harvest these species.

A Coast Guard Presence

During Operation North Pacific Guard in 2020, the USCGC Douglas Munro (WHEC-724) completed an international fisheries law enforcement patrol to deter IUU and provide a maritime enforcement presence on the high seas. Following a dozen at-sea boardings, including on Chinese squid fishing vessels, where numerous serious potential violations were identified, nearly the entire fleet of 31 vessels fled the fishery to avoid further inspection.9 This is a rather elegant example of robust maritime enforcement diplomatically delivered without firepower.

Operation North Pacific Guard is just one example of how the United States is positioning itself and the Coast Guard for the coming war on fish. In early 2021, USCGC Stone (WMSL-758) completed a deployment to South America in support of Southern Command and Operation Southern Cross, collaborating with international partners including Guyana, Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, and Portugal to combat IUU fishing in the region. The USCGC Bear (WMEC-901) deployed to West Africa in late 2020 to partner with Cabo Verde to counter IUU fishing.10 This joint patrol also provided a show of U.S. force in a region desperate for help.

Many vulnerable nations lacking sufficient resources are at risk from industrialized fishing fleets sponsored by aggressive great powers. One possible solution to counter this attack on sovereignty is for vulnerable nation-states to grant a modern-day version of “letters of marque” to the U.S. Coast Guard, delegating authority to protect their EEZs from illegal fishing for a specific period. Forward-deployed Coast Guard Maritime Enforcement Groups (MEGs) would deter IUU fishing and provide stability to vulnerable regions with soft power.

The MEG

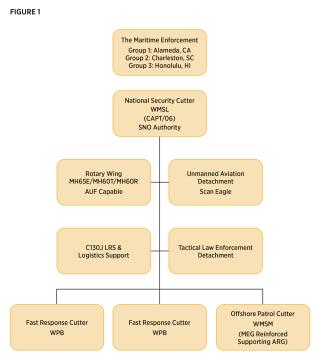

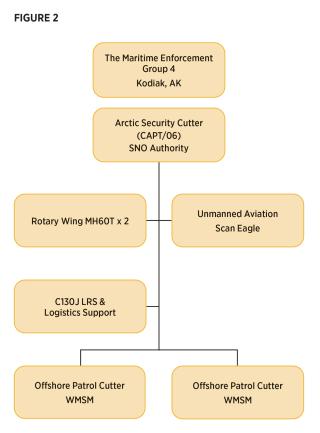

The Maritime Enforcement Group would be a formalization of emerging and established Coast Guard capabilities, providing both the Coast Guard area commander and the U.S. combatant commander a comprehensive force package capable of at-sea enforcement boardings, intelligence dissemination, long-range logistics, and search capabilities with supporting C-130J aircraft and shipboard rotary-wing assets. In addition, an embarked helicopter would be equipped for airborne use of force, to deliver warning shots and disabling fire to noncompliant vessels, along with supporting unmanned aerial systems.

A national security cutter (NSC) would be the nucleus of the MEG. With 60 days of continuous unsupported endurance and the ability to steam 12,000 nautical miles without refueling, it would be the cornerstone command-and-control platform. Joining this large cutter would be two Sentinel-class fast response cutters. With a range of 2,500 nautical miles and the ability to operate for a week unsupported, these smaller, more agile cutters would increase the footprint of the MEG and boost operational effectiveness. The Sentinels could be refueled and resupplied as required at sea by the NSC.

Because the operational tempo likely would be high, a tactical law enforcement detachment would be housed on the NSC to supplement boarding teams for the three assigned cutters. There would be five over-the-horizon-capable small boats in the basic MEG construct. In certain scenarios, an offshore patrol cutter also might be required to provide an additional flight deck and another asset capable of underway replenishment.

MEGs would give the combatant commander a rolling scheduling of availability, with one always available and key periods supported by multiple MEGs. Combatant commanders would have the flexibility to choose appropriate MEG deployment based on national security strategy and current events. To increase operational effectiveness, the NSC commanding officer would have delegated Statement of No Objection (SNO) authority supported by a detached legal representative and foreign shiprider from the country granting the letter of marque.

Because the MEG would be built around the NSC, shoreside support would be based at major NSC home ports. The ports of Alameda, California, Charleston, South Carolina, and Honolulu, Hawaii, would support MEG I, II, and III, while Kodiak, Alaska, would support MEG IV. MEG IV would be focused on Arctic security activities and be centered around the new Arctic security cutters. Each of these locations would require several shoreside support billets for planning and logistics.

A commander or lieutenant commander would serve as the MEG support officer, with a staff of petty officers in the storekeeper, yeoman, intelligence, and maritime enforcement specialist ratings to supplement the unit. A training, tactics, and procedures (TTP) manual would support an initial concept of operations for this deployable force package.

Conclusion

During his 2021 State of the Coast Guard Address, Commandant Admiral Karl Schultz reinforced that the Coast Guard provides soft power, multimission flexibility, trusted access, and nonkinetic options to advance U.S. interests, preserve security and prosperity, and address wide-ranging threats and challenges. The emerging crisis in the Pacific, fueled by the war on fish, will be an all-hands effort requiring naval ships, cutters, and aircraft. There may be no better way for the Coast Guard to contribute to future national security initiatives than by combating bad actors and enforcing international law to deter IUU fishing. Meet the Maritime Enforcement Group.

1. U.S. Coast Guard, “Operation North Pacific Guard 2020,” press release.

2. Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Seafood production,” Our World In Data, 2019.

3. Ling Cao et al. (2017). “Opportunity for Marine Fisheries Reform in China,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114 (January 2017): 435–42.

4. Fisheries Division, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. “Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles, the People’s Republic of China,” December 2017.

5. Cao et al., “Opportunity for Marine Fisheries Reform in China.”

6. Miren Gutierrez et al., China’s Distant-Water Fishing Fleet (Overseas Development Institute, June 2020).

7. Reuters, “Ecuador Jails Chinese Fishermen Found with 6,000 Sharks,” 28 August 2017; BBC, “Argentina Sinks Chinese Fishing boat Lu Yan Yuan Yu 010, 16 March 2016; Reuters, “ “Indonesian Navy Opens Fire on Chinese Fishing Vessel,” The Maritime Executive, 19 June 2016; and “Indonesia Sinks 51 Confiscated Fishing Vessels, 5 May 2019.

8. Alister Doyle, “Ocean Fish Numbers Cut in Half since 1970,” Scientific American, 16 September 2015.

9. U.S. Coast Guard, “Operation North Pacific Guard 2020,” press release.

10. ENS Malia R. K. Hindle, USCG, “The Long Blue Line: Operation “Relevant Ursa”—Bear training in West Africa,” MyCG, 3 November 2020.