The remnants of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 had barely thudded into the green farms of eastern Ukraine when the SA-11 antiaircraft missile system that shot it down drove back to the Russian border. A few hours earlier, the vehicle had carried its full complement of four rockets, and now, as it rolled back to Russia, the missing missile loomed above the driver’s compartment almost as conspicuously as did the nearly 300 deaths left in its wake.

Researchers investigating the tragedy uncovered a shocking amount of information about the SA-11. Its movement from garrison to the firing position had been documented extensively on social media, and analysts determined the origin of the convoy, its route through Russia to Ukraine, its chain of command, and the site from which it likely fired. They drew this information from publicly available sources—a staggering example of the potential of open-source intelligence.

The Marine Corps is developing operating concepts to focus on great power conflict. One such concept—expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO)—envisions emplacing an amphibious force inside the range of an adversary’s weapons to control key maritime terrain.1 Limiting the signature of this force will be crucial to its survival—yet the primary discussion about signature management for these expeditionary bases has centered on minimizing signals emitted by the bases’ military systems.2

Both the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine and today’s show the risks open-source information poses to the EABO operating concepts. If EABO is to be successful, it must address how publicly accessible information could betray a base’s location and composition.

Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17

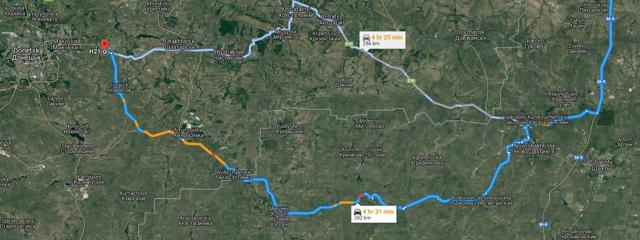

What follows comes from reports written by investigators working with information that in most cases was publicly accessible at the time of the events in question, information a great power could have used in real-time to inform the battlespace awareness of its forces. The Russian 53rd Antiaircraft Missile Brigade is headquartered near Kursk, a gritty industrial town south of Moscow. Between 23 and 25 June 2014, a military convoy from the base traveled almost 400 miles to the southeast, to the Ukrainian border.3 Based on painted markings and damage to the vehicles’ side skirts, investigators concluded the vehicles were SA-11s from the brigade’s 2nd and possibly 3rd battalions and that the convoy carried between 59 and 155 passengers along with the missiles.4 It was last spotted heading to a military airfield that housed a substantial amount of military equipment.5

There, this convoy separated into two groups. Some of the SA-11s returned north to Kursk, while at least one moved toward a known border crossing on 20 June 2014.6 On 17 July, a photograph and three tweets from residents indicated that this SA-11 and three tanks rolled through the city of Torez (separatist-controlled Ukrainian territory) around 12:20 pm. In the next hour, the SA-11 left its transporter truck, shed its tank escort, and began to move on its own. At 1:30 pm, it passed through Snizhne, where eyewitnesses noted that its crew looked like Russians and spoke with Moscow accents.7

Three hours later, it lobbed a missile into the sky, plucking Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 out of the air, killing its passengers and crew. A photograph documented a white vertical trail emanating from a wheat field near the last known location of this SA-11, and a video later released by the Ukrainian Interior Ministry showed this launcher, sans missile, driving back to Russia. The motto of the 53rd Antiaircraft Brigade is “We don’t fly, and we won’t let others.”8

Open-Source Bonanza

Focus on the SA-11 led to research into the 53rd Antiaircraft Brigade, and this revealed its equipment and personnel complement, command structure down to individual vehicle commanders, and more than 80 members of the 2nd Battalion.9

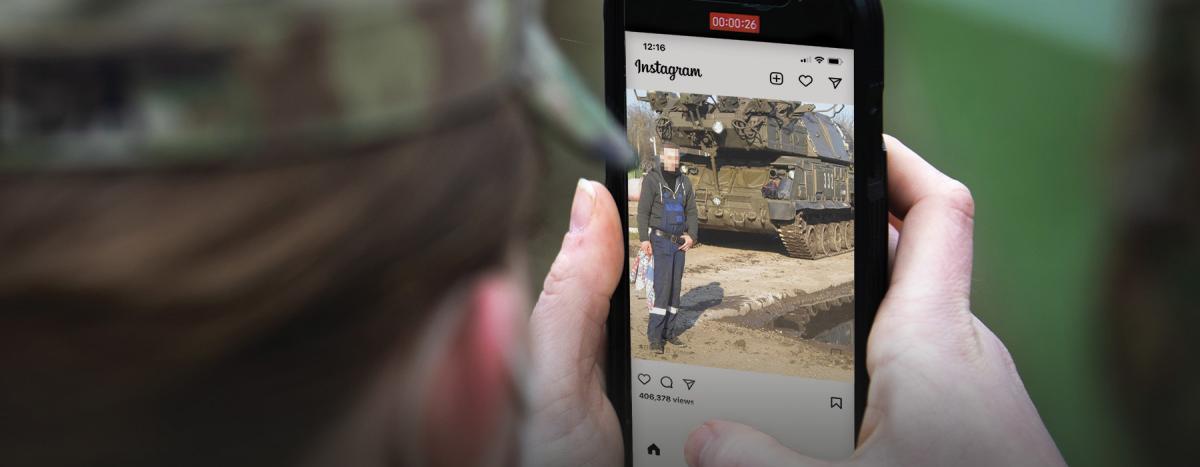

An astonishing amount of information about the SA-11’s journey is online. Its deployment to the border was intended to be a secret, yet the crew and their families littered a trail of evidence across the internet.10 Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union until 1991, and the eastern parts of the country have many similarities with Russia, yet Russian soldiers stood out to the local inhabitants—so much so that they were photographed repeatedly, and a local newspaper in Russia even ran a story about the convoy.11

Open-source information revealed much about the fighting in Ukraine in 2014, as it does today. Soldiers deployed to the Russia-Ukraine border uploaded photographs of themselves and their friends; their families were active in online forums about specific units.12 Investigators collected these clues and other open-source information, such as Google Earth images, with incredible effect. These are not mere conspiracy theories spread by keyboard warriors. During the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, numerous researchers cataloged the progress of Russian ground units in real-time using Google Traffic, among other sources.13

While the Bellingcat reports about 2014 were researched and written over the course of months by a nonprofit with limited resources, similar information can be collected and analyzed quickly today. And while this information may not be precise enough on its own for tactical use in targeting, for example, a peer nation-state could easily combine it with its technological resources and intelligence apparatus for much higher precision. The U.S. Air Force has used such blended intelligence to target the Islamic State since 2015.14 How will open-source intelligence apply to the Marine Corps’ new operating concept?

The Commandant’s Signature Concerns

The Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David H. Berger, is deeply concerned with signature management. In Force Design 2030, he argues that the force requires “lower signature . . . amphibious ships” and that changes should “equip our Marines with mobile, low-signature sensors and weapons.”15 The Marine Corps needs this equipment because, in the future fight, losing “the hider-versus-finder competition . . . has enormous and potentially catastrophic consequences.”16 The document concludes with a series of design fundamentals in which signatures again feature heavily.

General Berger expresses the same sentiment in the Commandant’s Planning Guidance.17 He intends to provide the fleet a “stand-in force capability to persist inside an adversary’s weapons systems threat range,” yet states that “our forces currently forward deployed lack the requisite capabilities.” These stand-in forces are intended to “take advantage of the relative strength of the contemporary defense” to create antiaccess zones in the face of precision weapons. The expeditionary advanced bases (EABs) from which they operate will be enabled by “smaller, low-signature, affordable platforms,” and stand-in forces will combine with the “low signature of the EABs” to create “an equally low signature force structure.”

The ideal force will be able to “create the virtues of mass without the vulnerabilities of concentration, thanks to mobile and low-signature sensors and weapons,” and “disguise actions and intentions, as well as deceive the enemy, through the use of decoys, signature management, and signature reduction.” General Berger argues the operational environment will be one in which “losing the hider-finder competition will result in attack by mass indirect fires.” Minimizing the signature of these EABs is a top priority for the Commandant.18

Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations

The Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations Handbook is deeply concerned with the signature of the force, so readers would expect it to have more to say on how to minimize an EAB’s signature. Yet, on that, it is strangely silent—a dangerous flaw. EABO will be executed in the kind of environment in which internet researchers were able to determine the SA-11 convoy vehicle commanders: a world in which publicly accessible information allows for the tracking and targeting of its bases. The Handbook’s focus on precision weapons ignores the dramatic changes in the information environment, and so the concept does not go into detail about minimizing the force’s signature to enable its survival.19

EABO purports to solve a problem—that the assumptions that have long underlaid the force structure have been invalidated by the advent of long-range precision fires.20 This is described in terms of a paradigm shift: The adversary’s developments have altered war so significantly that “concomitant” alterations to the force are required.21 But it is less that the increased range of precision weapons (which has been increasing for centuries) is new than that the explosion of information enables precision at long range. Focusing on a weapon while ignoring the changes to the information environment is nothing more than a “fascination with lethality at the muzzle end of our effort [that] often obscures how we will continue to feed the breech.”22 Although the concept acknowledges that “win[ning] the hider/finder competition will be the most pervasive and salient requirement of the inside force,”it does not consider the role of open-source information.23

If the Marine Corps intends for EABs to persist inside the adversary’s weapon range, then their survival depends on remaining undiscovered.

Modern Signature Threats

Constant connectivity is the norm for younger Marines, and it will be a basic expectation of coming generations. As a result, the service cannot ignore its online footprint. Rare is the Marine who lacks a cell phone, smart watch, or fitness device. Any of these could give away an EAB’s position.24 None of this is new: iPhones have had cameras for 15 years. Successful expeditionary operations will require coming to terms with the realities of modern information technology.

The knee-jerk response to online signatures has been to order Marines to leave phones behind when they go to the field.25 This is not illogical, as recent investigations have demonstrated the ability for an interested party to use publicly available information from applications to determine the user’s location.26 But it is easier ordered than enforced. Many young service members have never experienced life without cell phones—and will be exceedingly reluctant to give them up when instructed to do so. Nor does banning phones solve the greater problem posed by a sensor-enabled information environment. Marines will still be surrounded by civilians with cell phones capable of recording their every move. Even if every Marine gives up every device, this would not eliminate a formation’s online footprint. A single photograph from a third party could reveal its position. The SA-11 that shot down MH17 was less than 15 miles from the Russian border in a region with strong affinity for Russia. Yet civilians photographed the vehicles and soldiers several times on their way to a firing position.

The Corps’ new operating concepts are intended for use in the Pacific. Many of the islands on which these bases could be established are inhabited. Cell phones are everywhere. Marines will transit to shore from large gray ships on loud, clearly military connecting vessels. They will speak a different language, be dressed in uniforms, and will bring unique and interesting equipment. It is not as if the purpose of a rocket launcher on a truck can somehow be disguised; it is what it looks like. It is not possible to send Marines ashore without the awareness of everyone within eyesight (or cell tower range). On a modern battlefield that awareness will make its way online for collection by the adversary in near-real-time.27

The democratization of intelligence over the past three decades has been driven by making formerly restricted resources available for anyone to use. Satellite imagery used to be expensive, but today much is available free online, and the cost of launching satellites drops every year. Planet Labs is developing a fleet of inexpensive imagery satellites with the goal of imaging the entire Earth every single day, at a price unimaginable a decade ago.28 Almost any space-faring nation (particularly one with a record of industrial espionage) could field a similar fleet. An algorithm that identifies color and shape patterns could easily be used to scan vast amounts of imagery and to track objects of interest. The top-down visual pattern of most naval ships is idiosyncratic, for example.

In fact, something similar is already happening in the information environment. As the Economist details in its presciently titled article, “Small Cheap Satellites Mean There Is No Hiding Place,” Hawkeye360, a U.S. satellite company, was able to track the locations of illegal fishing vessels in Ecuador’s exclusive economic zone using faint reflections of navigation radars and communication equipment. The location data was accurate to within 500 meters of the signal’s origin, close enough to cue another source to fix the location—and even target it. These technologies are not limited to U.S. companies: British and French firms claim to be able to locate vessels to within 5,000 and 3,000 meters, respectively, with radio frequency signals alone.29 Hopefully the naval forces conducting EABO do not intend to use navigation radars or local communication devices at any point from embarkation to completion of mission.

Gone are the days of ships over the horizon being invisible. Emissions control no longer guarantees security; modern technology will allow the adversary to track the progress of a naval force or its EABs.30 No wonder the Commandant believes “visions of a massed naval armada nine nautical miles off-shore in the South China Sea preparing to launch the landing force in swarms of ACVs, LCUs, and LCACs are impractical and unreasonable” and concludes that the Marine Corps is underinvested in signature management.31

Managing EAB Signatures

This article does not take a position for or against the changes outlined in Force Design 2030, nor does it argue that EABO per se is bad. It took courage for a service in the throes of an identity crisis to assess the state of the Marine Corps and make the determination to spend years arguing for change.32 However, the concept is far from revolutionary. Fundamentally, it is nothing more than forward operating bases on islands with new weapons, and, by presenting itself as a revolutionary leap forward and cloaking its assertions in a shroud of unsubstantiated assumptions, it obscures many of the flaws that perhaps a different approach would have uncovered.33

The establishment of EABs inside the adversary’s weapon engagement zone is grounded in the idea that these bases will be undiscoverable. If they are discovered, then the idea of a survivable EAB falls apart. In fairness, the Handbook does acknowledge the centrality of signature management, stating that “signature management is a crux capability of all inside forces.”34 However, when I asked its principal author, retired Marine Colonel Art Corbett, about the feasibility of signature management in the information age, he told me it was not a concern.35 This possibly explains why the handbook avoids the issue with this sweeping assertion: “An adversary’s attempts to effectively strike capabilities aboard EABs with long-range ballistic and cruise missiles are mitigated by dispersion and passive protection activities such as decoys, cover, concealment, and frequent displacement” and assigns responsibility to the base commander without explaining how it can be accomplished.36 Nineteenth-century solutions to 21st-century problems.

To its credit, the Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations does seem to take signature management marginally more seriously, stating that a small signature is one of the enabling tenets of EABO and devoting six paragraphs to an explanation of the importance of signature management.37 The problem is that it provides no more concrete guidance than directing: “Forces conducting EABO [to] carefully manage signatures at all times,” and it seems to define signature only in terms of electromagnetic emissions.38 Likewise, Major Brian Kerg’s otherwise exemplary article in these pages details only the dangers of the signatures generated by the military systems employed by the forces executing EABO.39 What the Handbook, Tentative Manual, and Kerg article all miss is that a unit’s signature is composed of far more than its electromagnetic emissions. Yes, this is important, but not as important as the unit’s online signature—an area not substantively addressed in any of the EABO concept documents.

If researchers could discover the origin, route, and firing position of the SA-11 from information publicly available when it shot down flight MH17, what could an adversary determine about an expeditionary advanced base? On the future battlefield both sides will have access to more information than ever before. This reality will not change in the future. The mass of information can be used to locate EABs, track the forces operating from them, and destroy both. Unless there is a means of preventing open-source information from revealing the location of an expeditionary advanced base, the concept as currently described contains significant flaws. This, along with any other unvalidated assumptions in the concept, could be identified through an operational test in a functionally representative information environment.40 More work is needed before EABO is ready for prime time.

1. Col Art Corbett, USMC (Ret.), Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations Handbook: Considerations for Force Development and Employment, Marine Corps Warfighting Lab, Concepts & Plans Division, 1 June 2018, 11. This article primarily relies on the Handbook, as the original document describing expeditionary advanced bases. The Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2021) refines the ideas in the Handbook and is cited where the two substantively differ.

2. Maj Brian Kerg, USMC, “To Be Detected Is to Be Killed,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 12 (December 2020).

3. Bellingcat Investigation Team, MH17: The Open Source Investigation Three Years Later (2017), 3.

4. Bellingcat, MH17, 10, 13.

5. Maksymilian Czuperski, John Herbst, Eliot Higgins, Alina Polyakova, and Damon Wilson, Hiding in Plain Sight: Putin’s War in Ukraine (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2015), 5.

6. Bellingcat Investigation Team, Origin of the Separatists’ Buk: A Bellingcat Investigation (2014), 31–32.

7. Bellingcat, Origin of the Separatists’ Buk, 7, 8, 25.

8. Bellingcat, MH17, 8.

9. Bellingcat, MH17, 6, 23–56.

10. Bellingcat, MH17, 36–37.

11. Bellingcat, Origin of the Separatists’ Buk, 15.

12. Bellingcat, MH17, 36–37; “A Soldier of the 49th Artillery Brigade Was Seen in Donbas,” informnapalm.org, 12 December 2015.

13. See, e.g., “Ukraine Interactive Map,” liveuamap.com; Rachel Lerman, “On Google Maps, Tracking the Invasion of Ukraine,” The Washington Post, 25 February 2022.

14. Brian Everstine, “Carlisle: Air Force Intel Uses ISIS ‘Moron’s’ Social Media Posts to Target Airstrikes,” Air Force Times, June 2015.

15. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2020), 3.

16. Berger, Force Design 2030, 5.

17. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, 38th Commandant’s Planning Guidance (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2020).

18. Berger, Commandant’s Planning Guidance, 12, 14, 17.

19. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “The Case for Change: Meeting the Principal Challenges Facing the Corps,” Marine Corps Gazette (June 2020), 8–9. Gen Berger acknowledges the link between precision-strike and C4ISR technology. But the issue is framed in the context of C4ISR—the technical definition of which (ISR) does encompass open-source intelligence but in the vernacular usually refers to unmanned aerial systems.

20. Corbett, EABO Handbook, 11.

21. Corbett, 10–14.

22. Corbett, 61.

23. Corbett, 25.

24. Capt. T. S. Allen, USA, “Open Source Intelligence: A Double-Edged Sword,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 8 (August 2018).

25. Center for Strategic and International Studies, “The Future of Expeditionary Warfare with General Robert Neller,” video.

26. Foeke Postma, “Military and Intelligence Personnel Can Be Tracked with the Untappd Beer App,” Bellingcat (18 May 2020); Adam Meyers, “Danger Close: Fancy Bear Tracking of Ukrainian Field Artillery Units,” Crowdstrike, 22 December 2016.

27. Tim Moynihan, “New Twitter Tool Finds Hot Topics Before They Trend,” Wired, 29 January 2014.

28. Jon Markman “This Maker of Tiny Satellites Is Disrupting the Space-Industrial Complex,” Forbes, 28 May 2018.

29. “Small Cheap Satellites Mean There Is No Hiding Place,” The Economist, 10 March 2021.

30. Contrary to assertion in Corbett, EABO Handbook, 18.

31. Berger, Commandant’s Planning Guidance, 5; Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “Notes on Designing the Marine Corps of the Future,” Headquarters Marine Corps, 6 December 2019.

32. Leo Spaeder, “Sir, Who Am I? An Open Letter to the Commandant of the Marine Corps,” War on the Rocks, 28 March 2019; Dakota Wood, “Rebuilding America’s Military: The United States Marine Corps,” Heritage Foundation, 21 March 2019.

33. Capt Will McGee, USMC, “The Marine Corps’ Dangerous Shift to the Defense,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 11 (November 2021).

34. Corbett, EABO Handbook, 25

35. “Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations,” lecture and discussion, Marine Air-Ground Task Force Intelligence Officer Course, Information Warfare Training Center, Naval Base Dam Neck, June 2020.

36. Corbett, EABO Handbook, 4, 28, 66.

37. Headquarters Marine Corps, Tentative Manual, 1-5, 3-2, 4-10, 4-11.

38. Headquarters Marine Corps, 4-11.

39. Kerg, “To Be Detected.”

40. Capt Will McGee, USMC, “Testing Force Design,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 11 (November 2020).