Commandant of the Marine Corps General David H. Berger recently signaled that preparation for great power competition as outlined in the 2018 National Defense Strategy will require changes to the construct of the Marine Corps’ operating forces. General Berger and his predecessor both concluded that the Marine Corps is not “trained, equipped, or postured to meet the demands of the rapidly evolving future operating environment” because of several factors, most significantly the advent of a precision-strike regime.1

The Marine Corps’ force changes are intended to return the service to its traditional role as an expeditionary maritime force optimized for a naval campaign, through executing the principles outlined in the expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) operating concept. EABO is nested in the broader naval and joint distributed maritime operations, littoral operations in a contested environment, and joint access and maneuver in the global commons operating concepts. Under EABO, the Marine Corps envisions distributing expeditionary advanced bases around the area of operations to control key maritime terrain and to use as leaping-off points for further operations.

EABO is predicated on (at least) one fundamental assumption: The extended range of modern precision weapons has shifted the contemporary balance from offense to defense at the tactical level of war.2 The assumed increased relative strength of defense justifies placement of expeditionary bases. In the context of an operationally or strategically offensive campaign, tactically defensive positions should allow the Marine Corps to employ a bite-and-hold strategy on key maritime terrain to deny the adversary freedom of maneuver.

Marine Corps planners are taught that assumptions made during planning entail risk if they are not validated before execution. Planning expeditionary advanced base operations is no different. Assumptions must be validated unless the Marine Corps intends to accept risk when it employs the concept. But can the assumption that defense outweighs offense be substantiated?

Doctrinal Definitions

Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 (MCDP-1), Warfighting—the fundamental doctrinal publication of the Marine Corps—uses the terms initiative and response to differentiate offense from defense. Initiative, the pursuit of a positive aim, is most closely associated with offense. Response, the resistance to the adversary’s intentions, is associated with defense.3 MCDP-1 is careful to explain that neither offense nor defense can exist separately: They exist simultaneously as “necessary components of each other.”4

When the EABO Handbook states that defense is the stronger form of contemporary warfare, it is saying that the advent of precisions weapons has created battlefield conditions in which the strength of resistance exceeds that of initiative. Employing expeditionary advanced bases is predicated on this relationship: A tactical defense will prevent the adversary from achieving its intended goal. For example, an expeditionary advanced base equipped with precision weapons and placed on key maritime terrain will deny the adversary freedom of maneuver.

The Modern Advent of Defense

Fredericksburg, Virginia, lies a few miles south of Quantico alongside a major crossing point over the Rappahannock River. This crossing connects the roads running between Richmond and Washington, making the terrain useful for controlling movement between the two cities. In December 1862, it was the site of a major clash between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and Union Army of the Potomac. Confederate General Robert E. Lee situated his infantry on a sunken road along the bottom of the bluffs overlooking the town and sprinkled his artillery behind them and along the hills looming over the Rappahannock. Lee’s opponent, General Ambrose Burnside, crossed the river and sent his forces in a frontal assault against the entrenched Confederates, marching across the few hundred meters of open fields that separated the town from their trenches. Union soldiers were met by withering fire from Lee’s combined infantry and artillery and were repulsed with heavy losses.

Battlefield conditions in the early 19th century had favored the offensive because the integration of the three contemporary arms—infantry, cavalry, and artillery—allowed for the quick envelopment of an opposing force. The Battle of Fredericksburg, however, demonstrated how the increased accuracy and volume of contemporary rifled weapons had altered the relative strength of offense and defense. The destructive power of a defensive position could be seen in the casualties strewn in the killing fields in front of Lee’s positions, a major shift for soldiers raised in the contemporary school of military science that emphasized quick, aggressive operations focused on massing force at a decisive point and cutting the adversary’s supply lines.5

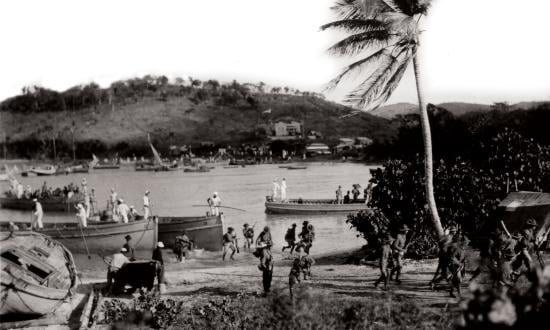

The invention of smokeless powder further increased the destructive capacity of defensive positions by hiding them from the adversary’s view, and this accelerated the shift to defense. The 1898 Battle of San Juan Hill, during the Spanish-American War, featured frontal assaults against a maze of barbed wire and trenches, and the first year of the South African War (or Second Boer War, 1899–1902) featured several open-ground advances against entrenched riflemen. In both examples, military leaders did not understand how new technology altered the conditions on the battlefield.6 As artillery pieces grew larger and more accurate, accompanied by the systematic employment of automatic weapons, the shift to defense continued. During World War I, resistance so outmatched initiative that, after the first months, both sides dug deep into the Belgian and French loam, praying they would not be ordered over the top.

This shift was not fully recognized at the time of the U.S. Civil War—Pickett’s charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, for example, demonstrates that even after Fredericksburg, Lee still clung to a legacy belief in the power of offense—nor would it be for decades to come. It should be mentioned that the relative strength of defense occurred only in battlefield circumstances involving Western, or Western-trained, opponents equipped with modern weapons. And even in those circumstances, the relative strength of the two forms of war depended on situation-specific conditions.

Back to Offense

Following World War I, with fires and the defense at their apogee, innovation changed the balance once again. The internal combustion engine drove tank treads and spun airplane propellers, allowing armies to skip over the muck of the Western front. Maneuver was back! The European theater of World War II featured the dominance of offense over defense, from the German Blitzkrieg circumventing the Maginot line to General George Patton’s drive across France. Although the locations and armies change, offense has remained—if one were to generalize across 70 years of history—the dominant form of conventional warfare, as seen during the 1967 Israeli-Arab Six-Day War, Operation Desert Storm in 1991, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

On the high seas, things are a little murkier. The story of naval action during World War II is of fleets hunting each other, so chalk one up for the offense.7 Sustained, large-scale maritime combat operations have not occurred since the 1940s, so history provides a far more limited record to examine. The 1982 Falklands War does hint at the strength of the offense: A British submarine sank the ARA General Belgrano, and HMS Sheffield was lost to a missile fired from an Argentine aircraft. The Atlantic Conveyer, a requisitioned merchant marine vessel, became a new target when chaff fired by HMS Ambuscade (the original target) diverted an incoming missile onto her.8 Each ship was sunk while in a defensive posture, indicating that at least under those circumstances, initiative exceeded resistance. But these were isolated incidents and far from conclusive proof.

What about a mixture of the two—when a naval force fights a land-based force? In the Age of Sail, as the EABO Handbook correctly points out, a “ship [was] a fool to fight a fort.”9 For wind-driven wooden ships, fighting a stone fort was suicide, as forts held larger cannons with greater range and accuracy and could fire heated shot intended to ignite the tinder-dry timbers of the ship. Shore-based defenses remained deadly to ships through at least the Civil War. Rear Admiral David G. Farragut’s order “damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead” during the 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay instructed his fleet to run through mined waters to escape the fires of land-based forts.

By World War II, the development of amphibious assault doctrine and naval aviation tilted the balance toward the offensive maritime force at an operational level, because the combination of the two could be used to suppress and then invade a shore-based defense. On a tactical level, however, the shore-based adversary had an advantage, as it controlled the terrain the landing force had to cross. After World War II, there has not been sustained combat between land- and sea-based modern forces. However, aerial assault and operational maneuver from the sea were intended to bypass the adversary’s strong points on shore, enabling initiative at the expense of resistance.

This brief examination of the historical record indicates that, since World War I, offense generally has been the stronger form of land warfare, and the limited data suggest this is true for naval operations as well.

How Precision Weapons Alter the Balance

General Berger makes a convincing argument that the advent of a precision-weapon regime has altered the conditions of a future maritime fight. Precision weapons (kinetic munitions capable of accurate targeting at long ranges) have allowed adversaries to develop areas in which they can deny freedom of maneuver to friendly forces. The EABO Handbook goes further, stating that “in the era of long-range precision weapons, the tactical maritime defense is the stronger form of battle.”10

Consider the sweeping generality of the Handbook’s statement. For every engagement, between any opponents, in every location in any type of war (low/medium/high intensity), the defense is stronger than the offense. Further, consider the magnitude of the assertion. Contrary to the past 80 years of conventional conflict, throughout which the range and accuracy of weapons have consistently increased along with the strength of the offense, the Handbook argues that the increased range of precision-strike weapons suddenly has altered the balance of war to make defense the stronger form.

The previous shifts between offense to defense were identified in retrospect, after years of warfare, during which some of the most significant participants did not recognize these changes. There is no doubt the increased range of precision weapons will affect a future naval conflict. But on what does the EABO Handbook base its assertion that the balance of war has categorically shifted to the shore-based defense?

Lacking primary source evidence (a littoral conflict between peer adversaries), one must turn to secondary sources to see if any of the major thinkers on the topic agree with the assertion. The most notable author discussing the potential impact of precision-strike weapons on the battlefield is Andrew Krepinevich, whom the Commandant cites to describe the precision-strike regime.11 Krepinevich’s 2015 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments publication, Maritime Competition in a Mature Precision-Strike Regime, describes the operating environment challenges expeditionary advanced base operations are intended to overcome. A close reading of the EABO Handbook indicates that it was heavily influenced by Krepinevich’s arguments.

Krepinevich does recognize that the absence of maritime combat in the last half-century limits the historical record used to support such a significant doctrinal change. Despite that, he believes because of the technological advances developed during the competition between the Soviet and U.S. navies, “modern scouting and cruise missiles were shifting the balance that had favored the defense at [the Battle of] Okinawa back to the offense.”12 He goes on to state that “at present, the competition favors the offense,” and “simply put, in the missile attack/missile defense competition, the attacker has the advantage.”13 This is common sense: Weapons that can shoot farther and more accurately are more likely to favor the side in pursuit of a positive aim (the offense). Thus, a report describing the impact of precision-strike weapons and authored by one of the most distinguished voices on the subject does not corroborate the claim that the presence of precision weapons favors the defense.

The Danger of Assumptions

The EABO Handbook’s belief in the strength of the defense does not appear grounded in fact, nor is it support-ed by the most prominent author on the subject. Yet, the newfound primacy of defense appears elsewhere in formal policy statements and articles about force design. For example, the Commandant’s Planning Guidance states that “stand-in forces take advantage of the relative strength of the contemporary defense.”14 Repeated in institutional policy documents, a belief in the relative strength

of the defense could become part of the Marine Corps’ collective consciousness, informing any number of decisions on personnel training, equipment, procurement, and the like.

The Marine Corps has embarked on a process to alter the structure of its operating force based on the EABO operating concept. The assumption that the contemporary defense is the stronger form of warfare is not trivial—it is a leap of faith that underpins a service-wide shift. This is why the Commandant called for discussion of the concept in these pages.15

The need for discussion is why it is so dangerous that distributed maritime operations, littoral operations in a contested environment, joint access, and maneuver in the global commons are hidden away on classified networks. Do similarly unsubstantiated assumptions lurk in the classified pages? The EABO Handbook is not even a definitive description of the concept—but it is the only explanation available. It is easy to imagine how an idea tumbling down the hallways of the Pentagon or at Headquarters, Marine Corps, spared of the free-and-fair exchange of ideas at the heart of any true innovation, could easily snowball into something more than it is.

The EABO Handbook begins with the premise that the balance has changed, and from that flawed starting point derives almost everything else. Precision weapons may have altered the balance to favoring defense. They also may have not. Until their effects can be conclusively determined—either through analysis of recent conflicts (Azerbaijan-Armenia, Ukraine-Russia, etc.) or by overwhelming agreement in secondary literature by independent experts whose analyses is not colored by a relationship with the Marine Corps—then the service should not base the most significant organizational changes in recent memory on an unproven assumption about changes in war.

Assumptions start small and, easily overlooked, grow like ivy at the base of a grand old oak tree. They slide innocuously upward, crawling along the trunk, slipping across the branches, becoming almost part of the tree itself, until their creeping tendrils reach out and infect the tree’s neighbors. Then they block the sun from the tree’s leaves, stealing its energy for themselves, sapping the tree’s strength. After a few years, the oak falls, toppled by something a casual observer probably never noticed.

1. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 2020): 2; Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “The Case for Change: Meeting the Principal Challenges Facing the Corps,” Marine Corps Gazette, June 2020, 8–10.

2. Art Corbett, Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) Handbook: Considerations for Force Development and Employment (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Warfighting Lab, Concepts & Plans Division, 1 June 2018), 23, 19, 6, 13.

3. U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1: Warfighting (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 2020), 35.

4. Warfighting, 35

5. Hew Strachan, European Armies and the Conduct of War (London: Routledge, 1983), 60–75.

6. Clay Risen, The Crowded Hour: Teddy Roosevelt, the Rough Riders, and the Dawn of the American Century (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019); Thomas Pakenham, The Boer War (New York: Random House, 1979).

7. The differentiation between offense and defense is less clear-cut at sea since naval conflict is, by nature, more fluid.

8. Andrew Krepinevich, Maritime Competition in a Mature Precision-Strike Regime (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2015), 56.

9. Corbett, EABO Handbook, 19.

10. Corbett, 9.

11. Berger, “Case for Change,” 8–9.

12. Krepinevich, Maritime Competition, 49.

13. Krepinevich, 72.

14. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Commandant’s Planning Guidance (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 2019), 10; Jake Yeager, “Expeditionary Advanced Maritime Operations: How the Marine Corps Can Avoid Becoming a Second Land Army in the Pacific,” War on the Rocks, 26 December 2019.

15. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “Together We Must Design the Future Force,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 11 (November 2019).