Having graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933 and earned his wings, future Vice Admiral Bernard “Smoke” Strean flew first with Fighting Squadrons 6 and 3 on board the USS Saratoga (CV-3) and then with Patrol Squadrons 11 and 23.

Following a tour ashore early in World War II, he commanded Fighting Squadron 1 attached to the USS Yorktown (CV-5). He led the squadron in the first attack on the Japanese fleet during the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 20 June 1944 and scored a direct bomb hit on a Japanese aircraft carrier. For this and other actions in the vicinity of the Marianas Islands, he was awarded the Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross with Gold Star, and the Air Medal with Gold Stars.

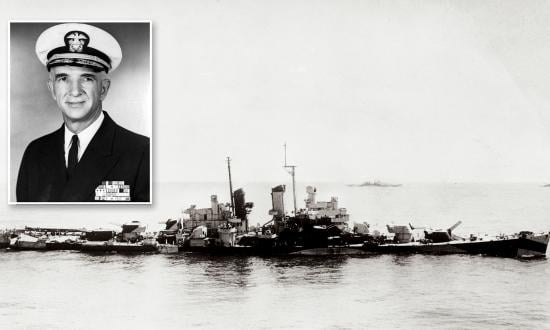

In 1964, then–Rear Admiral Strean took command of Carrier Division 2 on board the USS Enterprise (CVAN-65), with additional duties as Commander, Task Force One, the all-nuclear surface task force comprising the Enterprise and the USS Long Beach (CGN-9) and Bainbridge (DLGN-25). He led the three ships in Operation Sea Orbit, a nonstop around-the-world cruise.

(CVAN-65), Long Beach (CGN-9), and Bainbridge (DLGN-25) in Operation Sea Orbit, an around-the-world cruise. All photos U.S. Navy

He wrote in his March 1965 Proceedings Professional Note:

Until Sea Orbit, no ship in history had ever covered a route of 30,500 miles in 64 days. Task Force One covered the 30,500-mile track in this time, with 57 actual steaming days, keeping its schedule [including underway foreign visitors being flown on and off the Enterprise by her C-1 Trackers] almost to the minute. Throughout this period, the ships maintained a speed in advance of 22 knots, operating in all conditions of sea and weather. The three ships were in the Indian Ocean in the monsoon season, rounded Cape Horn during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter, crossed the equator four times, and, in all, experienced two winters, two summers, one autumn, and one spring.

In the following edited excerpts from his 1978 Naval Institute oral history, Strean looks back to the earlier days of carrier operations in the Pacific and his learning-while-flying in combat against the Japanese.

We joined the Yorktown in March or April 1944, attacked Guam, got quite a few airplanes in the air. I had read from pilots who had been in combat that if you got head-on with a Japanese airplane that you were not to worry. He’d always pull out. Believing that, two of us got in a position of being head-on. We continued on in to the very last instant, with him coming directly at us. He never flickered.

My wingman, who was a bit below me, must have started before I did, because he jumped over the top of him. I went underneath him, thought I had . . . collided with him, because it was so close. I turned around and looked behind me. There was a plane that went into the water. I thought it was my wingman, because we’d been taking a lot of projectiles from the Japanese pilot. I never did know who that was.

In my subsequent experience, I found out that when you attacked a position on the ground, you could be continuously firing six guns at the target. You were in formation with others. Sometimes you would fly into their shell casings, and they would knock holes in your wings, tear up your wings pretty badly. We were flying in formation, and we were knocking out windshields.

You have to set rules for some of these things. You fly formation, and you fly units of four. Where do the others fly so your shell casings don’t go through their windshields? It becomes the doctrine in the squadron, where you put the wing people. We just rearranged the pattern of formation flying and took care of that.

The Japanese had Orote Peninsula, quite an airfield at Guam. . . . I got hit twice there. Even a 40-mm bursting shell will blow a hole in your wing so big, you think you’ve been hit by a three incher.