America’s adversaries already are fighting a sophisticated, enduring, low-intensity war against the United States and its allies. China and Russia’s ongoing campaigns demand the United States restructure its agencies, strategies, policies, and resources to better employ irregular warfare (IW) and meet the challenge. The U.S. government’s current approach to strategic competition is problematic, but there are military, technological, interagency, and combined approaches that would enable the nation to stay ahead of its adversaries and keep competition from escalating to kinetic warfare. Fortunately, the Department of Defense has a large, capable organization, with forces deployed around the world, that can employ IW to prevail in great power competition (GPC): U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF).

The Challenge

The U.S. government’s approach to conflicts and wars tends to be event based, with clear beginnings and endings. China and Russia, however, view competition as ongoing: It escalates and declines in intensity but should remain under the threshold of combat. Peter Faber and James Callard explain Chinese combination warfare as drawing on “…virtually all spheres of human activity. It has this capacity because it relies on military, non-military, and above military to promote or prevent, expand or localize, and vitalize or neutralize various threats.”1 Similar to China, James Sherr explains that Russian President Vladimir Putin has directed Russia’s military and intelligence services into close alignment with the country’s political objectives. Russia’s “new generation” or “hybrid” warfare methodology, “is designed to blur the thresholds between internal and interstate conflict and between peace and war…. to achieve strategic objectives before the adversary realizes that the war has begun.” U.S. adversaries are perfecting methods of mixing soft and hard power, employing them against the United States and its allies on a continuous basis. In comparison, Callard and Faber further explain, the United States “practiced combination warfare both episodically and unsystematically during the 1990’s, especially against Iraq and Osama bin Laden.”2 The United States continues to employ elements of national power episodically, segregated among various agencies, and further separated by domain and region in the DoD.

Chinese IW Strategy:

China’s perspective of national power is broad and includes several elements which the U.S. government considers either irrelevant or in the realm of private industry and non-governmental organizations. China uses soft power and competes in issues the United States often does not even recognize as a part of a wider conflict. Rand’s Andrew Scobell explains, “China’s current perspective on its relationship with the United States is centered on competition that encompasses a wide range of issues embodied in China’s concept of comprehensive national power.”3 Along with the obvious issues of defense and diplomacy, China’s authoritarian government considers technology, cultural, and internal stability issues essential to national power. China sees a future where “war becomes increasingly civilianized,” relying on non-military means to neutralize threats and gain advantages over competitors.4 The U.S. may not recognize some of these issues are part of the competition, but the authoritarian Chinese Communist Party (CCP) uses all these means to build advantage.

Chinese manipulation and theft of valuable U.S. science and technology (S&T) is a recognized danger. Chinese intelligence services acquire U.S. and other nations’ scientific research and technology through methods that include: hacking, sending Chinese students and researchers to study and work at western institutions of higher education, and purchasing U.S. companies. William Holsten explains, “There is a massive, coordinated assault taking place on American technology, perhaps the largest, fastest transfer of intellectual property in human history, and much of it is taking place on U.S. soil.”5 In 2017, China passed a legislative framework directing all Chinese to contribute to state security.6 The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) assessed, "It is likely that citizens can be compelled to assist PRC state actors in interference efforts if and when those efforts fall under the broader definition of 'national intelligence work' and 'national intelligence efforts' as noted in the Law.”7 This assessment in combination with the approximately 350,000 Chinese students attending U.S.’ universities, gives China an incredible capacity to use espionage to procure developing technology.8 A second aspect of the theft of science and technology is the acquisition of U.S. businesses and their subcontracted suppliers by PRC-backed private companies. One example is the acquisition of A123, a U.S. company that develops and supplies lithium-ion batteries.9 A123, after receiving approximately $1 billion from private investors and $100 million in federal government backing, as well as technical advice from General Motors, Motorola, and QualComm, went bankrupt and was subsequently purchased by the Chinese Wanxiang Group Corp for $257 million.10 This acquisition gave China the company’s technological research and manufacturing facilities at an incredibly discounted rate.

Within the U.S. government, multiple agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, National Security Agency, Federal Trade Commission, work on different aspects of this problem. They observe, detect, and respond individually to the Chinese intellectual property theft. A coordinated U.S. government effort would be more capable of detecting the Chinese malign behavior, creating comprehensive deterrence, and formulating a powerful response.

What Can DoD Do?

DoD recognizes traditional hard power is a single dimension of grand strategy. The Pentagon has accepted GPC as an enduring operational reality. The Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy (IW annex) states, “U.S. approaches to IW have been cyclical and neglected the fact that IW—in addition to nuclear and conventional deterrence—can proactively shape conditions to the United States’ advantage in great power competition.”11 Even if DoD uses conventional forces and SOF in an enduring fashion, without a comprehensive interagency effort, the United States will fall short in meeting the challenge China poses. The National Security Strategy (NSS) states, “To meet these challenges we must also upgrade our political and economic instruments to operate across these environments” and “By aligning our public and private sector efforts we can field a Joint Force that is unmatched.”12 Clearly, synchronicity across the U.S. government and coordination with private industry is required.

To employ IW successfully against peer adversaries, the USG will need a strategy that expands past episodic fusion of various agencies and partnerships to a more enduring model. Strategy is “the employment of the instruments (elements) of power (political/diplomatic, economic, military, and informational) to achieve the political objectives of the state in cooperation or in competition with other actors pursuing their own objectives.”13 The U.S. can create an enduring IW GPC strategy to conduct measured actions through a Joint Interagency Task Force (JIATF), that combines resources and authorities. Individual members of a JIATF will need to call on their partners in private industry to pursue necessary technology and expertise needed to address Chinese advantages in economic and technological IW. An overarching JIATF can ensure the ends are properly supported with enough means and ways properly planned and executed to reduce strategic risk.

DoD lacks the structure and methodology to synchronize the capabilities of its various services, combatant, and functional commands to conduct global irregular warfare. To tackle these problems, U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) could act as the synchronizer for all USG IW efforts as the single global coordinating authority. SOCOM could also lead DoD’s efforts to collaborate, coordinate, and execute an irregular warfare strategy for great power competition across the interagency, with private industry, and with international partners.

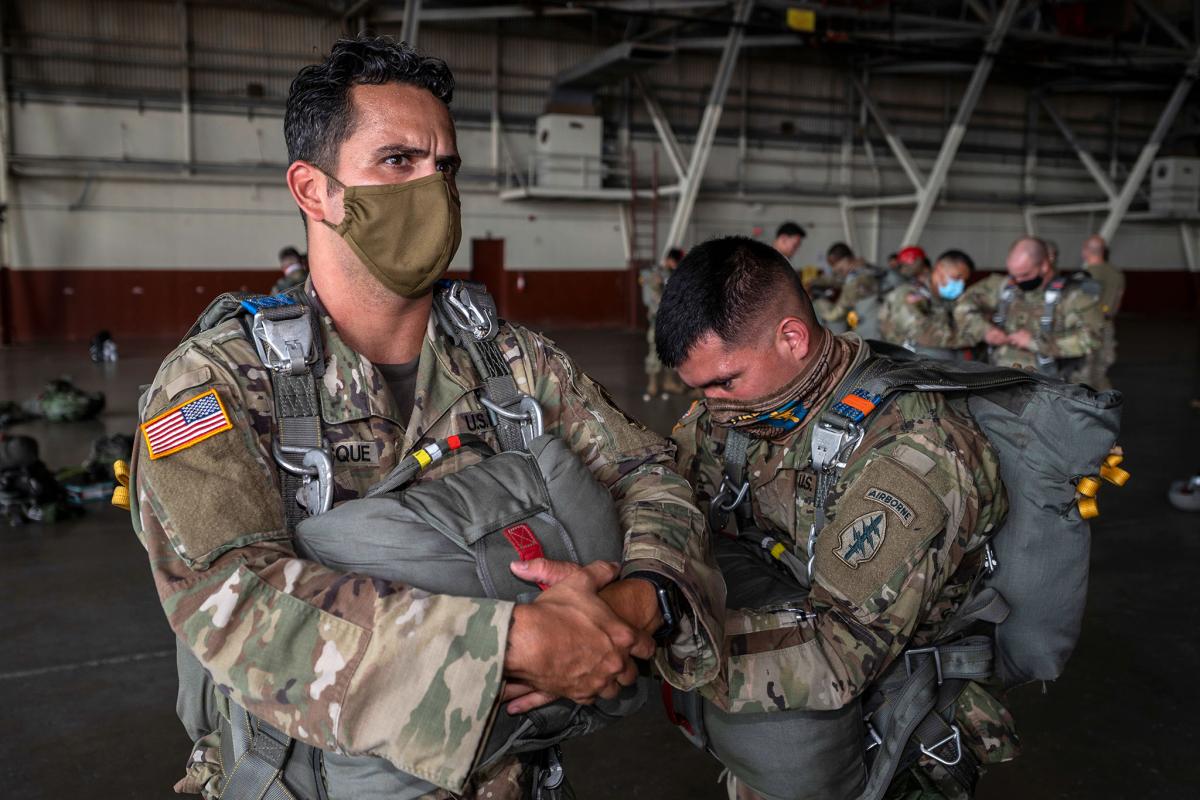

whole-of-government efforts to counter adversary irregular warfare. JIATF-South in Key West,

Florida (shown here) oversees U.S. efforts to thwart illegal drug smuggling, human trafficking,

and transnational criminal threats. U.S. Special Operations Command could lead a similar JIATF

aimed at irregular warfare. (U.S. Air Force image by Marianique Santos)

Establishing a global IW coordinating authority to synchronize conventional and special forces would be a complex but achievable endeavor. The IW annex of the NDS states DoD “must institutionalize irregular warfare as a core competency for both conventional and special operations forces.”14 Though SOCOM is not the sole executer of IW under this annex, there are reasons to make it the overarching global coordinating authority. First, several specific IW missions are SOF core competencies, including unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, and counterterrorism (CT).15 SOCOM counterproliferation weapons of mass destruction (CWMD) and counter threat finance missions are applicable to GCP IW as well. SOCOM and its assigned forces already possess the expertise not only to conduct the operations themselves, but the training institutions to expand CF comprehensive of IW. Second, compared to a regionally aligned combatant command (COCOM), SOCOM’s activities are not restricted to a specific geographic region. Regional COCOMs focus only on the great power in their area of responsibility. Currently, U.S. European Command primarily focuses on Russia, with minimal reasonability to address China’s activities in their region. SOCOM, therefore, is a reasonable answer to this specific issue. Third, all service branches are represented in SOCOM. Lastly, as the global coordinating authority for CT and CWMD, it has already proven its expertise in coordinating activities across the COCOMs, services, the interagency, and with U.S. international partners.

Way Ahead

Through the lens of America’s primary adversaries, GPC is an enduring low-intensity war, below the threshold of combat. China and Russia combine all elements of national power in a near continuous and enduring manner, while the United States bifurcates its efforts among its various agencies in a more episodic approach. China’s theft of U.S. science and technology is just one an example of their ongoing IW efforts, which the U.S. has been unable to deter, and against which will require a more enduring and combined interagency strategy. To confront these challenges, the United States should establish a joint interagency task force to better command and control irregular warfare efforts—and SOCOM is the logical choice to lead that task force.

1. James Callard and Peter Faber, “An Emerging Synthesis for a New Way of War: Combination Warfare and Future Innovation,” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 3, no. 1 (2002): 63.

2. Callard and Faber, “An Emerging Synthesis for a New Way of War,” 63.

3. Andrew Scobell et al., “China’s Grand Strategy: Trends, Trajectories, and Long-Term Competition,” July 24, 2020, xiii–xiv, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2798.html.

4. Callard and Faber, “An Emerging Synthesis for a New Way of War,” 63.

5. Holstein, William J., The New Art of War: China’s Deep Strategy Inside the United States (First Edition Dering Harbor, New York: Brick Tower Press), 2020, 16.

6. David McGuinty, “National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians Annual Report 2019” (The National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (Canada), August 30, 2019), 60, https://www.nsicop-cpsnr.ca/reports/rp-2020-03-12-ar/annual_report_2019_public_en.pdf.

7. McGuinty, 60.

8. Holstein, William J. The New Art of War: China’s Deep Strategy Inside the United States, 51.

9. Holstein, 71.

10. Holstein, 70.

11. Department of Defense, “Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy Summary” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, 2020), 2.

12. White House, National Security Strategy (Washington, DC, 2017), 28, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

13. Yarger, H. Richard. "Towards a Theory of Strategy: Art Lykke and the Army War College Strategy Model." U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Policy and Strategy (2006): 107-112.

14. Department of Defense, “Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy Summary,” 3.

15. Joint Publications 3-05, Special Operations, 2011, II–5, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA543873.pdf.