In fall 1944, the Senate amended the legislation that created the Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service (WAVES) to authorize its officers and enlisted personnel to deploy outside the continental United States, to the territories of Alaska and Hawaii. Lieutenants Eleanor Rigby and Winifred Quick were the first two WAVES to report to Hawaii, paving the way. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz authorized them to travel as the only passengers on a Pan Am Clipper loaded with official mail. There would be some 5,000 WAVES on the islands by the time the war ended.

There was a pressing need for their service. “They did exactly the same jobs there that they did in the States,” Rigby recalled in her oral history published by the U.S. Naval Institute.

Some of them were even assembling and repairing airplanes. We had officers who flew back and forth teaching navigation to the young aviators coming along. Communicators, we had a lot of them out there, because Wahiawa is the big relay station. Everything that came from Washington to the Pacific had to go through Wahiawa. They worked three shifts.

Eleanor Grant Rigby graduated from Smith College in 1918. With World War I raging, she wanted to join the Smith College Relief Unit in France but was too young. As World War II engulfed Europe, she worked for the Connecticut Defense Council from 1941—prior to Pearl Harbor—until 1942. When the initial WAVES bill passed, she was invited to 33 Pine Street, New York, interviewed, and recruited as one of the first WAVES. After completing her physical exam—skirting two separate rooms of naked men in the process—she was commissioned as a lieutenant (j.g.), WV, probationary.

Following her own training back at Smith College, Rigby returned to New York City to help set up and guide the large WAVES training operation at Hunter College.

There was nothing there that was not new and not a problem, from uniforms, housing, and meals in this pioneering work. It took 10,000 eggs for breakfast. We used one and one-half tons of salt a month. Whenever they had baked beans, they used half a ton of beans. I hadn’t been there long when one of the old chiefs in commissary came in almost in tears and said “Lieutenant Rigby, we had beans on the menu this morning, a great Navy thing, and the girls wouldn’t touch them.”

I said, “No, Chief, we’re not used to beans for breakfast.” He said, “What am I going to do with them?” I said, “Try them for lunch.” He did and there wasn’t a bean left. The same thing happened about serving salads at noon. The girls insisted on getting salads.

Rigby recalled a particular event from her time in Hawaii. “One of the highlights of my Navy career was when Representative Margaret Chase Smith came out—the only woman —with the House Armed Services Committee.” As the senior WAVE, Rigby was her escort, with car, for the three-to-four-day visit.

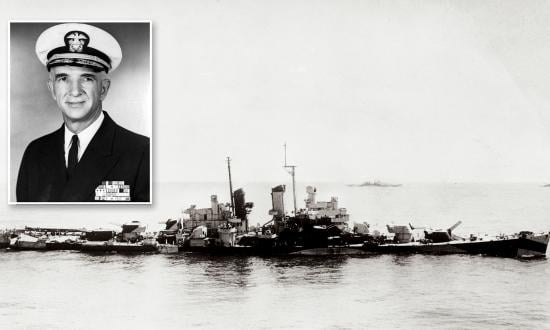

Admiral Nimitz was going to take all the Armed Services Committee out to the old USS Saratoga (CV-3) for a day and show them everything, the landings, the take-offs, the shooting at targets, everything that a flattop did, and we were told to be at Baker Able docks at 0730. Representative Smith was at the Halakalone. I got her; brought her out; and there were these three admiral’s barges drawn up.

By that time, Nimitz was five-star admiral of the fleet. Admiral Spruance was there. We boarded the admiral’s barge and went across to North Island, which was where the carriers tied up. It was probably two or three blocks to walk from where the barges landed to the flattop.

But we didn’t walk. Limousines were drawn up, one with Nimitz’s five stars on the front. As we boarded, I started for one of the jump seats. Admiral Nimitz said, “Oh no, you sit there.” Here is a lieutenant commander sitting in the back seat of this big limousine with Margaret Chase Smith, and on the two jump seats right in front of us are Fleet Admiral Nimitz and Admiral Spruance. I reminded Admiral Spruance of that and told him it was the only time I had ever really seen him laugh.