In early September 2019, the Category 5 Hurricane Dorian stalled over the northern Bahamas for two days, taking its place in history as the most destructive storm to hit the island chain. The U.S. Navy was tasked to provide humanitarian relief with helicopter sea combat (HSC) and helicopter mine countermeasures (HM) squadrons from Helicopter Sea Combat Wing Atlantic (HSCWL) in Norfolk, Virginia. This relief effort resulted in eight search-and-rescue (SAR)/tactical evacuation missions, with 108 survivors recovered and transported; 417 passengers transported; 29,000 pounds of food and water delivered; and 203,850 pounds of cargo delivered.

Not only was this foreign disaster relief response extremely successful, it also was the first time in the Navy’s history that a foreign relief mission started and ended each day from a continental U.S. base. The dynamic environment raised critical medical, logistical, communication, and human factor concerns that can inform preparations for wartime.

Early Operations

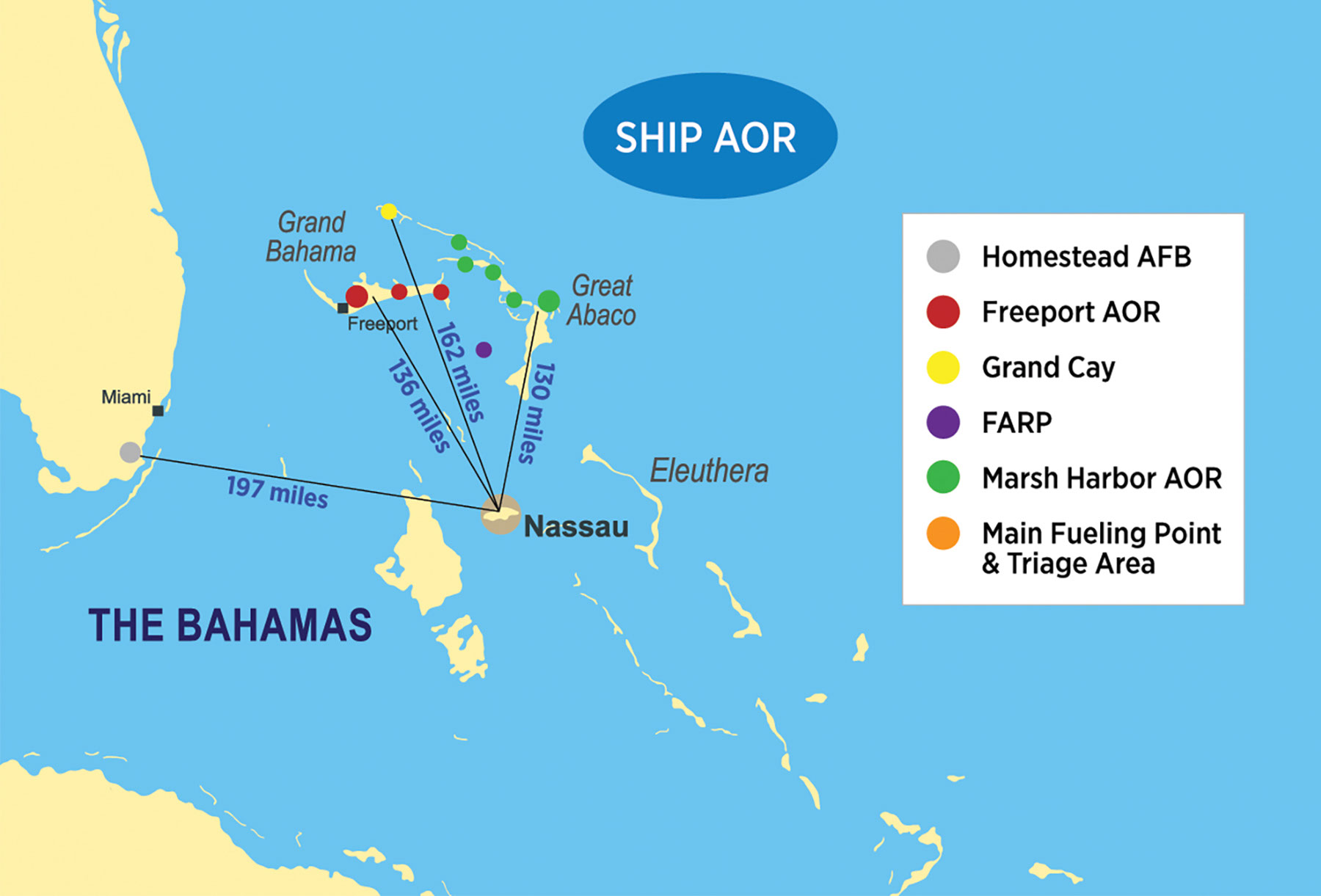

HSCWL began flying missions within nine hours of its arrival at Homestead Air Reserve Base in Florida, traveling the 197 miles to Nassau, Bahamas. That transit took approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes each way, depending on weather and winds. Initial reports indicated the only fuel source was Nassau International Airport, at Odyssey Aviation’s fixed-base operation (FBO). This FBO is also where the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Virginia Task Force 1 (VA-TF1) teams were being based to support all initial relief.

During the confusion of getting mission tasking together in the first days of flying, the FBO was overwhelmed with rotary- and fixed-wing traffic. The average wait time for a fuel truck was more than an hour. Distance and limited fuel were the two major challenges to crews during the entire relief effort, not unlike what Navy and Marine Corps operations in geography such as the South China Sea would be like. With fuel available only in Nassau, flight planning had to be extremely conservative, because the overwater distances were significant (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1

Flying the first missions in the objective areas, crews quickly found themselves landing to assess crowds waving the helicopter down, transporting USAID personnel into certain areas, or evacuating patients being turned over to HSC crews. Communications were a critical challenge in early tactical evacuation missions. In the majority of the objective areas, communications were limited unless there was an undamaged cell tower or if communications with a designated relay aircraft worked. The majority of communications came from using commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) unclassified applications, such as “WhatsApp.”

Ad Hoc Evacuation Missions

SAR and tactical evacuation tasking were unpredictable for crews. With the extremely limited communications, crews conducting other missions often found themselves getting mid-mission tasking to rescue a survivor.

Medical supplies and logistics for critically ill patients was another serious issue. Crews often arrived on scene with no information on the patient’s injuries or condition. In two instances, HSC crews were forced to refuse a tactical evacuation mission because they did not have the proper gear to safely care for the patient. In both cases, the patients required sedation, ventilator management, and a capable ambulance service–level provider to care for them during the lily-padding back to Nassau. Not all HSC crews fly with these equipment capabilities or this level of qualified personnel. Further complicating matters was the fact that both critical patients were left in a resource-limited environment with few medical supplies and no alternative evacuation asset immediately available. Unfortunately, crews would later learn that one of the patients had succumbed to his illness.

Additional issues included unplanned patient transport requests, such as when during a cargo transport mission USAID members rushed an HSC crew with a sick patient to be transported back to Nassau. At other times, aid workers reported severely dehydrated survivors on certain islands, forcing HSC crews to break tasking if fuel was available to perform a rescue. Island hopping, limited fuel, and the requirement to bring all patients back to a single staging area overwhelmed by aircraft posed an extraordinary challenge.

In any disaster relief scenario, medical providers anticipate treating large numbers of casualties with polytrauma or those requiring critical-care medical services. While those patients did present on a few missions, the majority were suffering from chronic conditions with no treatment available. Many patients were without food and water and suffered severe dehydration. Most critical patients transported became sick because of the inability of local healthcare resources to manage chronic illnesses. The lack of infrastructure and extremely limited health care required crews to manage exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, heart failure, diabetes, hypertensive emergencies, and complications from missed dialysis sessions.

Communications

A few crew members had the ability to communicate through a Garmin inReach beacon. The inReach uses the Iridium satellite system, and it gave crew members access to text messages anywhere they were operating. The inReach was, however, a personal device that became a reliable asset to maintain communications while transiting between islands or when in objective areas where cellular service was still out.

Air-to-ground communications were a consistent challenge throughout the relief effort. The PRC-149 SAR/Survival radio has documented reliability problems going back more than ten years, and they showed up during this relief mission. Aircrews on deck, navigating through debris, or evaluating patients had no communication with aircraft for the first few days. HSCWL leaders were able to secure PRC-148 and -152 radios loaded with nonsecure common working area frequencies, which minimized confusion and helped crews maintain communications in a fluid environment.

Flying in the islands became problematic because of the overwhelming number of fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft. All communications in the air took place with advisement calls on a common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF), even at airports that normally were controlled by towers. There was only a single CTAF for the Marsh Harbor, Treasure Cay, and Eastern Freeport objective areas, where the majority of the relief efforts were focused, resulting in hundreds of aircraft operating on a shared CTAF.

Satellite communications could be a reliable option in disaster relief, if available to all relief crews. However, the military limits the use of this capability during tactical missions. Having over-the-horizon communications with other aircraft and being able to update or take tasking immediately would be a critical safety measure for all operating crews.

Emergency Clinical Medicine

Five days after the storm, a crew was tasked to transport a USAID survey team to Grand Cay Island, a small island north of Freeport. The USAID team asked to have a search-and-rescue medical technician (SMT) from the aircraft remain with them because of the unknown amount of time the survey team needed to stay on Grand Cay. The SMT contacted the island’s councilman to evaluate if there were any emergency medical needs. Grand Cay had a small clinic, but the staff evacuated prior to the storm and had not returned. While the structure remained standing, it had flooded. With help from the local community, the SMT cleaned a treatment area and assessed the condition of the clinic’s supplies.

After the clinic cleanup, community members gathered outside to be evaluated. As in other parts of the islands, some chronic medical conditions had been left unmanaged. The SMT evaluated more than 35 patients who had heard a “medical provider” was at the clinic. An SMT is primarily trained to treat point-of-injury medical and trauma cases and to provide en route emergent care for acute and chronic medical conditions. Of the 35 patients, 6 required clinical procedures, ranging from multiple sutures, diabetic evaluations, tooth removal, and care for a high-risk pregnancy. The lack of medical infrastructure in the entire area crippled the ability to provide proper care for patients. Even if a patient was evacuated to Nassau, the medical capacity there was overwhelmed.

Lessons for War

Because of the transit times in the area of operation, crews found themselves flying longer than normal. The round trip from Homestead to Nassau could take more than three hours. Crews would then operate for four to six hours after receiving their tasking, including the transit and lily-padding times between islands.

While average logged flight hours ranged from eight to ten, there were logistical, fueling, on-deck, and mission planning times that often made for 16-hour HSC duty days. HSCWL was initially a small detachment supporting the relief operations. But crews found themselves operating on an unsustainable daily cycle, and it became apparent that, given the operational tempo, more personnel would be needed.

The Hurricane Dorian relief effort suggests that crews are not ready to operate remotely in a wartime environment from an island base with limited communications, fuel, command and control, and information on personnel injuries. Relief crews constantly experienced communication outages that, in a threat environment, would have had direct negative effects on mission effectiveness and safety. In addition, while the other services have inflight refueling capability for their rotary-wing assets, Navy MH-60 helicopters do not have this option. Having that capability would increase force support and lethality in wartime operations.

In the wake of a mass casualty event or combat operations in the maritime environment, the inability to get to the scene quickly will prevent Navy medicine from providing critical care within the “golden hour.” Remote operations with limited fueling options and communication challenges make it extremely difficult for crews to rapidly gain a tactical understanding of the situation. A delayed response could result in many patients waiting more than 48 hours from the onset of injury and illness for evacuation and treatment, as Hurricane Dorian victims experienced. At that point, many illnesses had become much worse because of deteriorating environmental conditions and resulted in patients experiencing dehydration, sepsis, malnourishment, and heat injuries.

The most important factor in a successful initial response is being mission ready. The HSC community is not at present ready for the force health protection and tactical evacuation response missions. Underfunded commands are failing to meet the doctrine of being advanced-life-support capable. Poor communication ability and a lack of medical supplies—such as appropriate monitors, point-of-injury consumables, ventilators, and required medications to treat casualties—will continue to put lives at risk.