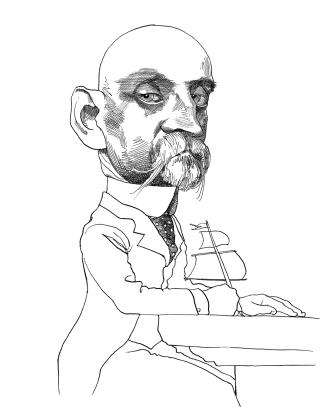

For generations of U.S. naval officers, Alfred Thayer Mahan has been the sea power prophet, The Influence of Sea Power upon History 1660–1783 the naval bible, and “command of the sea” his legacy. Ironically, fewer people have read that book than have drawn reference to it or appreciate its provenance.

Kept pierside in Peru by insufficient funds to buy coal for the steam sloop USS Wachusett in 1884, Captain Mahan made use of the English-speaking library ashore. His reading of Theodor Mommsen’s The History of Rome provoked Mahan to wonder how history would have changed had Hannibal Barca invaded Rome by sea instead of the arduous land route across the Alps.

From that question would flow The Influence of Sea Power, published by Little, Brown and Company in 1890 while Mahan was president of the Naval War College. But Mahan was a historian, not a strategist in today’s sense. None of his more than 40 essays and books were written on what today could be called naval strategy, and none contained a specific definition of what “command of the sea” meant or how it was to be achieved, especially in a modern age in which naval warfare was becoming three dimensional—in the surface, air, and subsurface domains. Mahan was indeed the greatest publicist for sea power, and he was indisputably a fine historian, but strategy was not his strong suit.

Summarized, Mahan’s argument was neo-mercantilist. Nations depending on the seas for trade and commerce needed navies to protect routes, bases, and other logistics, enabling access to markets and resources, including stations to refit and refuel. Competition arose for bases and markets, and navies were vital in defeating, blockading, or sinking rival navies to achieve “command.”

This led to the notion of decisive sea battles in which capital ships battled other large ships, producing victory or defeat. But this view of command and decisive sea battles was illusory.

The sea is rarely—if ever—fully commanded. The ordinary state of oceans is “un-commanded,” unless a permanent force can guarantee that other navies are incapable of contesting specific areas. This is one reason the U.S. Navy has preferred the term “control of the sea”—to signify temporary possession over permanent command. The same logic applies to controlling the air.

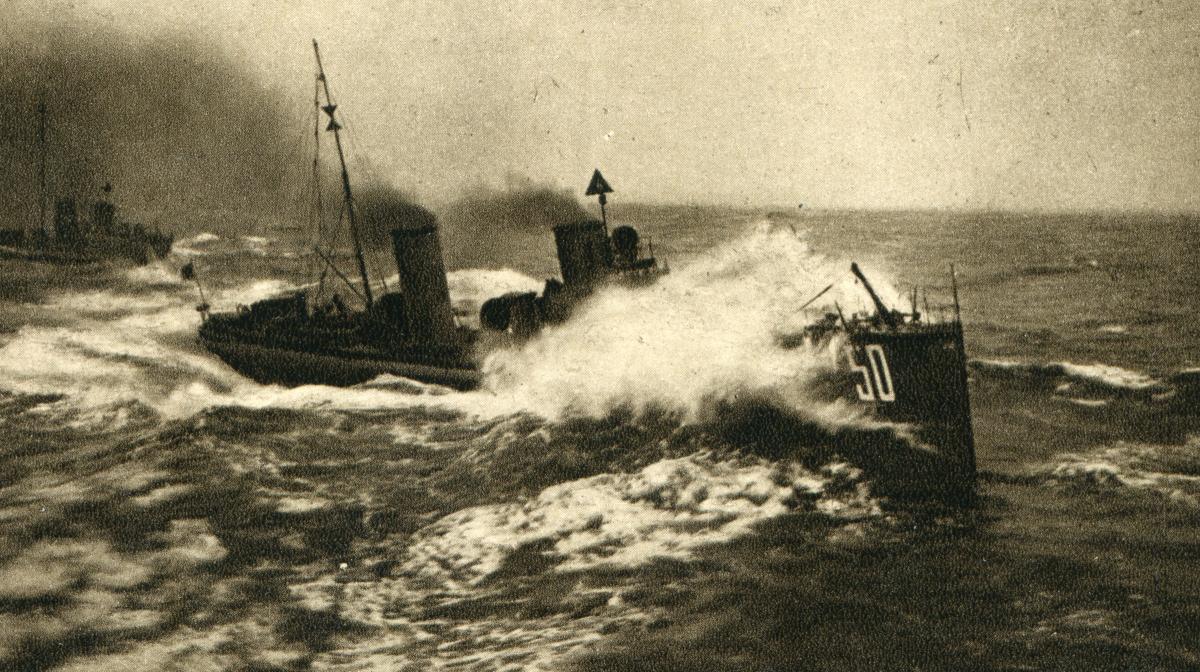

And, in any case, decisive sea battles almost never end wars, certainly not since Trafalgar. On 21 October 1805, Vice Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson routed a combined French-Spanish fleet commanded by Admiral Pierre Villeneuve, capturing 21 of 33 ships-of-the-line and sinking one. Yet it took another decade until Arthur Wellesley, Lord Wellington, defeated Napoleon at Waterloo to finally close the Napoleonic wars. At Jutland in 1916, while Royal Navy Admiral John Jellicoe could have lost World War I in an afternoon, he could not win it, and in the end the battle was indecisive. These events suggest that naval victories may be necessary conditions for overall victory, but also insufficient ones.

Even in the Pacific during World War II, by mid-1944, the Japanese Navy had been neutralized, except for kamikazes and a few submarines. But Japan’s defeat came about because of two atom bombs that “shocked and awed” the high command into surrender. The only alternative appeared to be an invasion by soldiers and Marines, not further naval activities.

Had there been no U.S. Navy engaged in the Korean, Vietnam, Afghan, and (two) Iraq wars, would the outcomes have changed?

What might Mahan write today, updating his Influence of Sea Power? First, he might reverse his title to read The Influence of History on Sea Power, citing how the roles and uses of navies have changed by analyzing the rationale for Russian and Chinese maritime forces and considering the emphasis on “active defenses” rather than decisive sea battles. He also would have to determine how globalization has affected competition and whether his thesis of states being drawn into battle over bases and access still applies.

Second, he would have to assimilate the technological revolutions that have transformed warfare. While three dimensions of naval warfare were emerging at the end of Mahan’s life in 1914, “strategy” remained divided between the sea and the land, with each usually developing along different and independent lines. He would have read the December 2020 triservice maritime strategy Advantage at Sea, with its plan to increase the size of the Navy to more than 355 ships in the coming decades. He may have asked if the principal roles of “sea control” and “power projection” were too limited and whether other diplomatic, coercive, and fleet-in-being missions were ignored. And he might have thought that the arguments for sea power were too tame and thus likely to be dismissed.

Clearly, Mahan would grasp the importance of the nuclear deterrence role of navies as confirmation of his fleet-in-being concept, but with far greater strategic value. He might ask if the infamous notion of mutual assured destruction made conflict at sea more likely, in the way he saw competition over bases, colonies, and foreign markets in his own day.

The cyber and space warfare domains might not pose much challenge to his arguments. Mahan was well aware of rudimentary radio and understood that underwater cables still carried the bulk of international message traffic; long-distance communications were another thing bases and navies must protect. He would probably regard space as he did the sea—vast and normally uncontested, but crucial to strategy and the ability to wage war.

Third, it is unlikely he would be happy with the educational changes, particularly at the Naval War College, that diverted away from history and extensive use of war games and battle programs.

Fourth, he would need to consider what should constitute a “capital ship” today. Would they even need to be ships, given the growth and capability of air and missile power? Perhaps Mahan would write a follow up titled The Influence of Science and Technology on Sea Power.

Would Mahan still argue for “command of the seas” and winning decisive battles as the metrics for sea power? China seeks to make economic and financial inroads into foreign markets through its Belt and Road Initiative. How would these affect Mahan’s neo-mercantilist views? More than likely, he would understand China’s dependence on the seas for global access as increasing and justifying that country’s quest for sea power.

Mahan would probably feel comfortable with the composition of carrier and amphibious strike groups. He would appreciate the shift of the short-range main cannon batteries of his day to aircraft and missiles with long and even intercontinental reach. And he would be impressed by the capability of nuclear and diesel submarines to influence sea power.

As a historian, Mahan knew well that disconnected strategies invariably failed in peace or war. In observing the wars of the 20th and 21st centuries, Mahan would need to amend “command” and “decisive” to acknowledge the political-strategic nature of international competition and the foolishness of attempting to address it with individual strategies divided among discrete domains.

That worked in Mahan’s day, when battle was essentially limited to the surface of the Earth, either land or sea. Where Mahan asked, more than a century ago, what if Hannibal had come by sea, today he might ask, what if he comes by air or space? His answers would make for great reading.