Current plans, if not modified, could lead to an overreliance on GPS-based systems for critical transportation functions.”1 These words ring as true today as they did in 1997, when they were written in the report of the President’s Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection. That plan—to discontinue the Coast Guard’s LORAN-C radionavigation system, an alternative to GPS—was enacted in 2010.2

Since then, great power competition has exacerbated the vulnerability of the U.S. GPS infrastructure, and there has been a lack of urgency among government agencies charged with developing a new, enhanced LORAN (eLORAN) system. The Coast Guard, however, is uniquely positioned to ensure the U.S. military will be equipped to deal with the consequences a great power conflict may inflict on its GPS infrastructure. It is time for the Coast Guard to take the lead on eLORAN.

Threats to GPS

GPS already faces meaningful threats from U.S. near-peer competitors. “Russia and China are making advances in developing counterspace systems faster than we are protecting our satellites,” asserts Tom Harrison, director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Both countries can hack and shoot down satellites and are even developing “co-orbital” attack methods to compromise them with their own spacecraft.3

In addition, jamming attacks drown out satellite signals, and spoofing can fool a GPS system into following false signals. Russia likely has caused 10,000 spoofing incidents, while, since 2010, North Korea has jammed GPS signals for thousands of aircraft and hundreds of ships and cell towers.4 Some of the most advanced spoofing technology has been detected in Chinese ports.5 High-ranking government personnel have warned that “a coordinated spoofing-jamming attack against various systems in the U.S. would be easy, cheap and disastrous.”6

U.S. overreliance on GPS has compounded these vulnerabilities. Colonel Richard Zellman, former commander of the Army’s First Space Brigade, explains:

Our force structure today is built around the assumption that we have GPS and we have satellite communications. . . . When you start taking away those combat multipliers, we need to go back then to the days of the industrial-age army where you have to have three times as many people as the adversary does.7

Loss of GPS would be especially catastrophic to the Maritime Transportation System the Coast Guard is charged with managing and protecting. Today, ships’ navigation and control systems are seamlessly integrated with GPS, as evidenced by the elimination of Mode III chart navigation from the 2020 Coast Guard Navigation Standards. A GPS outage could result in simultaneous maritime accidents and shipping delays. Aviation, too, depends on “uninterrupted access” to GPS.8

While GPS typically is associated with navigation, it also plays a critical role in timing for countless systems. Cell phone towers, power grids, financial systems, computer networks, military communication systems, train controls, emergency service dispatching, Doppler radar weather reporting, and seismic monitoring systems all rely on GPS timing.9 The Coast Guard is testing synthetic aids to navigation that use the Automatic Identification System (AIS), another technology that depends heavily on GPS.10 The U.S. mainland remained unscathed through two world wars, but a modern conflict with a near-peer competitor could deprive Americans of countless vital GPS-dependent systems in an instant.

GPS denial in a future conventional battlespace should be considered a foregone conclusion. Russia has tested this capability in Syria, and, according to former commander of Special Operations Command General Tony Thomas, Syria is “the most aggressive electronic warfare environment in the world.”11 Fortunately, there is a solution.

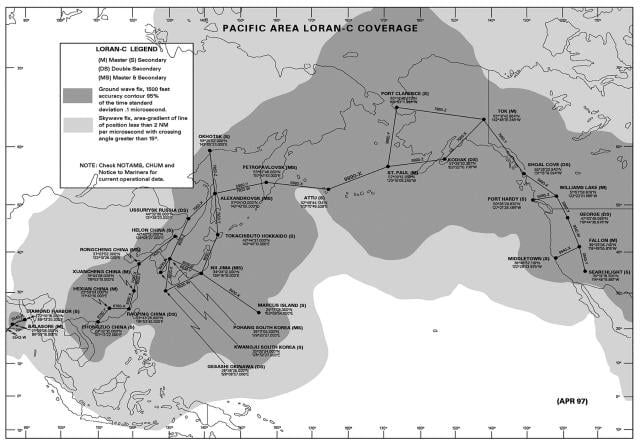

The Coast Guard operated the LORAN-C radionavigation system for 52 years, but it was fully decommissioned in 2010 as an “unnecessary” expenditure. A newer variant, eLORAN, can use preserved LORAN-C infrastructure, be received indoors, and provide a critical coordinated universal time (UTC) signal.12 According to an UrsaNav study in conjunction with multiple government agencies, eLORAN “has great potential as an alternate and complementary timing source to GPS.”13 Retired Air Force colonel and lead GPS architect Brad Parkinson corroborates this assessment, maintaining that eLORAN “is the only cost-effective backup for national needs.”14

Let the Coast Guard Lead

When it comes to eLORAN, the Coast Guard’s experience makes it the right organization to lead the way. No other agency shares the Coast Guard’s combined expertise in seafaring, aviation, GPS outage investigation, and aids to navigation. The Coast Guard maintains more international relationships than any other military branch, and it can leverage them to expand eLORAN’s global coverage.

The Coast Guard has an obvious interest in promoting eLORAN to protect the Maritime Transportation System. However, the service’s lesser-known responsibility to provide aids to navigation in support of military operations could afford the Coast Guard the justification to accelerate the establishment of functional eLORAN. U.S. law clearly obligates the service not only to “develop, establish, maintain, and operate” aids to navigation, but also to do so “with due regard to the requirements of national defense.”15 This legislation coincides with a need for a GPS backup across all military branches.

The Coast Guard may not share the offensive capabilities of other branches, but it could field a deterrent that would enable the bulk of U.S. military operations to continue in a GPS-denied environment. Based on its legal authorities, the Coast Guard can ensure that in a great power conflict, U.S. warfighters will be equipped with both a domestic and a deployable terrestrial backup. The National Timing Resilience and Security Act requires the GPS backup system to “be capable of deployment to remote locations.” Modern eLORAN could protect U.S. forces from the localized GPS spoofing that followed Russia’s military into Syria.16 The Coast Guard could train to deploy mobile eLORAN stations to an area of conflict in support of all U.S. forces fighting a near-peer competitor.

In his 2020 State of the Coast Guard address, Commandant Admiral Karl Schultz specified his intent “to employ [the Coast Guard’s] unique authorities and capabilities to complement, not duplicate, [DoD] efforts.”17 An eLORAN capability would embody the essence of “complementing” and not “duplicating” DoD efforts. Like Coast Guard redeployment assistance and inspection detachment teams who inspected containers for the U.S. Army in Afghanistan, forward-deployed eLORAN units could provide a unique Coast Guard capability to its DoD contemporaries.

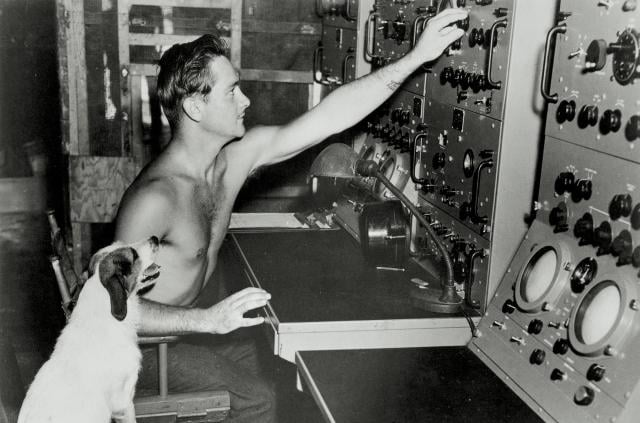

The Coast Guard is authorized to establish “aids to air navigation required to serve the needs of the armed forces of the United States peculiar to warfare and primarily of military concern.”18 In this spirit, the Coast Guard can decouple from its maritime roots to offer eLORAN operation in a future battlespace. This would not be the first time Coast Guard–operated LORAN supported other military branches during wartime. Coast Guardsmen constructed LORAN stations “on islands almost as soon as they had been taken back from the Japanese” during World War II and were similarly employed in Korea and Vietnam.19

Establishing eLORAN with a national defense focus also could help the Coast Guard pay for the system. A clear mutual interest in a GPS backup exists among the U.S. armed services. The need to make alternate timing services available for all U.S. military users as well as civilians, specified in the National Timing Resilience and Security Act, can justify the allocation of DoD funding for the eLORAN program. This arrangement could be especially helpful to the Coast Guard, whose budget is a fraction of the other branches’ budgets.

If the federal government entrusts eLORAN to the Coast Guard, the service must prioritize these efforts. In The Russia Trap, George Beebe identifies eLORAN development as a “resilience” strategy, which exists in contrast to a “stability” strategy. He explains that stability strategies aim to make all things equal and can be counterproductive, while resilience strategies “acknowledge the inevitability of change and the probability of shocks” and seek to mitigate such hazards.20 In a Coast Guard context, sending cutters to the South China Sea may be viewed as a stability strategy that is less critical than the need for a GPS backup. A terrestrial GPS backup system could cost about $350 million, which is 19 percent of the Coast Guard’s 2020 budget for drug interdiction operations.21 The system is a worthwhile expenditure even if the Coast Guard must fund it alone. eLORAN would not only support DoD efforts, but also safeguard the homeland from the type of chaos the Coast Guard was transferred into the Department of Homeland Security to prevent.

The Bering Strait may be an ideal starting point for eLORAN. The Coast Guard struggles with poor GPS signals in high Arctic latitudes, and LORAN is a potential solution to this problem.22

In anticipation of great power competition, the 2018 National Defense Strategy asserts: “There can be no complacency—we must make difficult choices and prioritize what is most important to field a lethal, resilient, and rapidly adapting Joint Force. America’s military has no preordained right to victory on the battlefield.”23 This statement calls on the joint force to do what it must to prepare for a future conflict, no matter how unorthodox the solutions. Establishing eLORAN would allow the Coast Guard to make a vital contribution to military readiness while minimizing the new risks such a conflict could pose to Americans at home.

Though the United States is a great power, we must remember we have no “preordained right” to a functioning GPS.

The Dangerous Radio- Navigation Capability Gap

The United States is an outlier in its lack of a GPS backup system. Its near-peer adversaries, Russia and China, have heavily invested not only in methods to disrupt GPS, but also in establishing terrestrial-based backup systems to satellite-based technologies.1

According to Dana Goward, president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, “The Russians believe . . . when they go to war, all signals from space will be blocked because it’s really easy to block signals from space—why would you not do that?”2 Russia takes radionavigation seriously in a way the United States does not. It is testing the military radionavigation system known as “Sprut-N1.” As the title of a 2019 article by the Russian publication Izvestia states, “When Satellite Goes Down, the Navy Will Receive Ground GPS.”

Russia already maintains three coverage zones for its version of a LORAN system called Chayka and, in its 2019 radionavigation plan, has noted intentions to establish a radionavigation system along the Northern Sea Route.3 China’s radionavigation system is integrated with Russia’s through the Far East Radio Navigation Service.4

In a future conflict, opponents may quickly disable each other’s satellite systems with space-age weaponry, but victory could be determined by which military is able to best use a rudimentary, relatively low-cost, terrestrial backup. This existing gap could embolden near-peer adversaries to act more aggressively against U.S. satellites, because U.S. retaliation would have a lesser effect on their terrestrial-based systems, while their actions could cripple the U.S. military and economy. Despite the risks, Goward notes that the U.S. military “is not really considering what’s not happening. They’re dealing with today.”5 This sentiment was displayed when DoD ultimately refused to build and fund a terrestrial GPS backup, because doing so “wasn’t the department’s job.”6 LORAN should become the Coast Guard’s job again.

1. Robert T. Marsh, Critical Foundations: Protecting America’s Infrastructures (Washington, DC: President’s Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection, 1997).

2. U.S. Coast Guard, “LORAN-C General Information,” U.S. Coast Guard Navigation Center, 6 August 2012.

3. Niall Firth, “How to Fight a War in Space (and Get Away with It),” MIT Technology Review 122, no.4 (July/August 2019).

4. Nick Higgins, “GPS Is Easy to Hack, and the U.S. Has No Backup,” Scientific American, 1 December 2019; BBC, “Study Maps ‘Extensive Russian GPS Spoofing,” BBC, 2 April 2019; Gerard Offermans, Erik Johannessen, Charles Schue, Jonathan Hirschauer, and Ed Powers, “UTC Synchronization and Stratum-1 Frequency Recovery Using eLoran: The Alternate Basket for Your Eggs,” Proceedings of the 45th Annual Precise Time and Time Interval Systems and Applications Meeting (Bellevue, WA, December 2013): 163–72.

5. Dana Goward, “Patterns of GPS Spoofing at Chinese Ports,” The Maritime Executive, 19 December 2019; Mark Harris, “Ghost Ships, Crop Circles, and Soft Gold: A GPS Mystery in Shanghai,” MIT Technology Review, 15 November 2019.

6. Higgins, “GPS Is Easy to Hack, and the U.S. Has No Backup.”

7. “The U.S. Military Is Preparing for War without GPS,” Agence France-Presse, 20 December 2017.

8. Higgins, “GPS Is Easy to Hack, and the U.S. Has No Backup.”

9. Dan Glass, “What Happens If GPS Fails?” The Atlantic, 13 June 2016.

10. U.S. Coast Guard, “How AIS Works,” U.S. Coast Guard Navigation Center.

11. “Above Us Only Stars: Exposing GPS Spoofing in Russia and Syria,” C4ADS, 26 March 2019.

12. Offermans et al., “UTC Synchronization and Stratum-1 Frequency Recovery Using eLoran”; Stephen Bartlett, Gerard Offermans, and Charles Schue, “Innovation: Enhanced LORAN,” GPS World, 23 November 2015.

13. Offermans et al., “UTC Synchronization and Stratum-1 Frequency Recovery Using eLoran.”

14. Glass, “What Happens If GPS Fails?”

15. 14 U.S. Code § 102: Primary Duties.

16. “Above Us Only Stars: Exposing GPS Spoofing in Russia and Syria,” C4ADS.

17. ADM Karl Schultz, USCG, “2020 State of the United States Coast Guard: ‘Why I Serve,’” 20 February 2020.

18. 14 U.S. Code § 102: Primary Duties.

19. Scott Price, “The Legacy of Loran,” Coast Guard Compass, 4 February 2010.

20. George Beebe, The Russia Trap: How Our Shadow War with Russia Could Spiral into Nuclear Catastrophe (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2019).

21. Glass, “What Happens If GPS Fails?”; ADM Karl L. Schultz, USCG, “Posture Statement: 2021 Budget Overview” (Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters, 18 February 2020).

22. John Sheridan, “LORAN Could Be Used for Alaska GPS Corrections,” AIN Online, 8 May 2008.

23. Secretary James Mattis, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy” (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2018).

The Dangerous Radio- Navigation Capability Gap

1. Kate Murphy, “The U.S. Has a GPS Problem,” The New York Times, 23 January 2021.

2. Connie Lee, “Spoofing Risks Prompt Military to Update GPS Device,” National Defense, 4 January 2018.

3. “Plan for the Development of Radio Navigation for 2019–2024,” Commonwealth of Independent States, 24 October 2019.

4. Dana Goward, “China Expanding LORAN as GNSS Backup,” GPS World, 12 October 2020.

5. Lee, “Spoofing Risks Prompt Military to Update GPS Device.”

6. Dana Goward, “$15M for GPS Backup Demo Part of Congress’ March to Terrestrial PNT,” GPS World, 16 January 2019.