From the moment the doors to Bancroft Hall shut on Induction Day plebe summer, the U.S. Naval Academy inundates midshipmen with leadership lessons. Flag and general officers and distinguished civilians share leadership experiences with the brigade through the Forrestal Lecture Series every month. An entire academic department staffed with high-performing officers is devoted to the study of leadership (it is aptly named LEAD). Case studies based on every imaginable decision-making scenario are presented to midshipmen during several courses and seminars. The Naval Academy even hosts an annual leadership conference, which brings some of the best minds in management and motivation the world has to offer.

With all that time and money invested in my leadership training, I was primed to react to the statement, “The Army doesn’t care about having well-trained surgeons. . . . It only cares about having bodies,” in an October 2019 U.S. News article describing several Army surgeons’ critiques of the military health system.1 If I had slept through those leadership classes and studied calculus instead of listening during Forrestal Lectures, the Naval Academy still would have found a way to teach me the first law of leadership: Care about your people. Of course, the Army does not want its highly trained medical professionals to feel like they are simply numbers—that the service they care so much about does not care about them—but the systems that govern training and skill maintenance in military medicine make this difficult to avoid. This problem is not unique to the Army. The medical communities within each service are at the pinnacle of what it means to be “joint,” such that the problems in Army Medicine are undoubtedly similar to those in Navy Medicine.

Late on a cold October night, I was searching the internet about military surgery (I plan to attend the Stanford University School of Medicine beginning in fall 2021). I expected to find an easy-to-read and detailed description of the goals and subtypes of military surgery. Instead, I stumbled on a troubling number of articles describing different parts of the same problem: proposed budget cuts to military healthcare, the need for an operationally ready medical force in the new era of near-peer competition, and the actual medical force complaining through anonymous forums about their lack of readiness and skill decay.

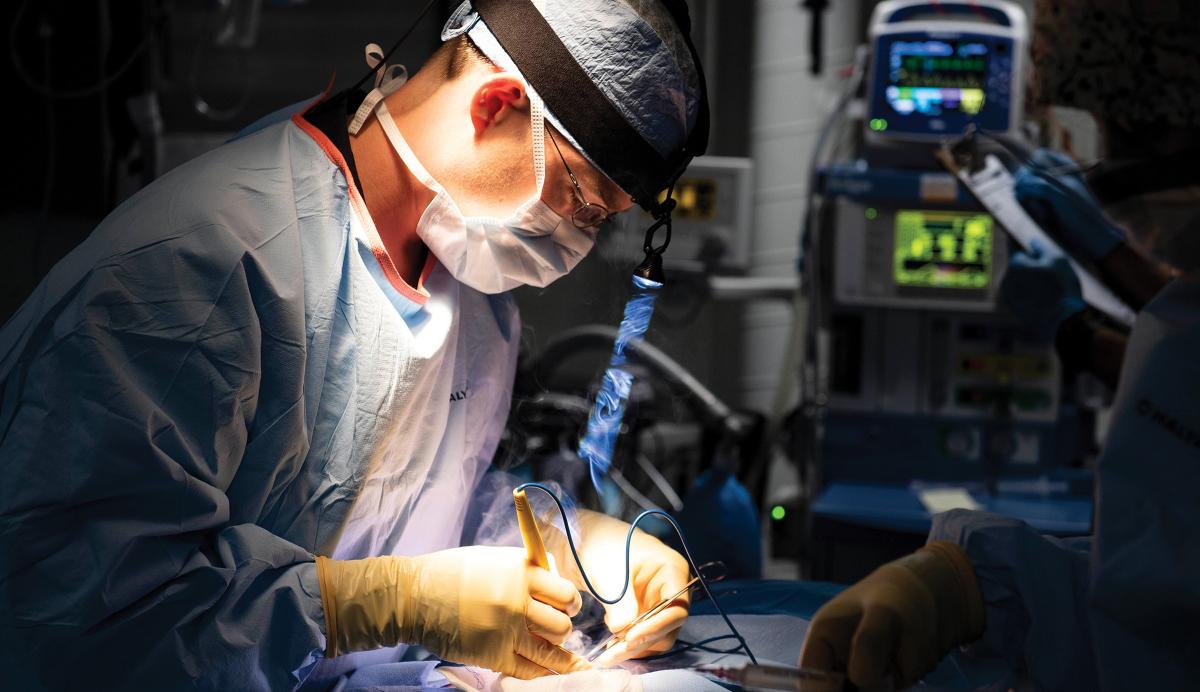

In April 2018, another report from U.S. News stated that military surgeons at base hospitals across the country perform a variety of procedures at very low volumes.2 This is because the military’s patient population is young and healthy compared with the general population. Until conflict breaks out, surgical patients are few and far between. Much of military surgery, including trauma surgery and emergency medicine common to combat environments, is rarely practiced. Lower volume of practice in medicine is correlated with poorer outcomes. Moreover, Navy surgeons want to operate. They want to help others. They have spent years training to perfect their profession and hate seeing their skills waste away. Why should military physicians train less than their civilian counterparts in the trauma fields of medicine that were practically invented as a result of warfare? This is “practice makes perfect” without the practice, and therefore without the perfect.

Imagine an active-duty service member requires a life-saving procedure after sustaining an injury in combat. For certain complex, high-risk procedures, civilian surgeons with an industry-average case volume have a case fatality rate (the chance that the patient dies in or after surgery) of about 5 percent—lower than that of surgeons at military hospitals, which generally have more volume than forward-deployed surgical assets. Because the forward-deployed surgeon has not had as much practice, the case fatality rate jumps from 5 percent to 10 to 15 percent.3 This is the equivalent of requiring a winged pilot to get behind the controls of a relatively unfamiliar aircraft (though they may have undergone a few training flights, one with an instructor), and then ordering him to perform perfect close-air support. This would not be allowed to happen in other service communities; why should it happen in medicine?

Part of the extensive leadership training for every Naval Academy midshipman is a one-semester course on ethics. One could question the ethics of allowing military surgeons to operate in peacetime if the paucity of opportunities means they have worse patient outcomes than those of their civilian counterparts. However, the reason to do so is consistent with the Class of 2021’s motto: We need to operate in peacetime to prepare for war. Therefore, the answer is not to prohibit military surgeons from performing low-volume surgical procedures, but to find them more opportunities to operate. Medical service members (healthcare professionals included) must feel they are equipped and prepared for service in the nation’s next conflict.

Better Military-Civilian Medical Partnerships

Navy-civilian medical partnerships are not new. Military medicine outsources some of its residents (physicians fresh out of medical school) to civilian programs to meet manpower requirements. In addition, former Surgeon General of the Navy Vice Admiral Forrest Faison established partnerships between Navy Medicine and hospitals in Chicago and Jacksonville to allow Navy corpsmen to work in civilian hospitals for 12-week periods to experience trauma medicine. Navy Medicine also allows a portion of its physicians every year to enter civilian fellowships or subspecialty training (for example, programs in which a general surgeon trains to become a heart surgeon). These partnerships allow Navy Medicine to maximize medical operational readiness and fill manpower needs. However, many more partnerships are needed to prepare Navy surgeons for battlefield trauma.

Navy Medicine should rotate a larger portion of its mission-critical active-duty healthcare personnel into civilian hospital systems for skill maintenance. With a surgeon shortage in the United States, many civilian hospitals could use salaried military physicians instead of the costlier, procedure-based reimbursement structures of private healthcare.4 During rotations, the private hospitals employing the military physicians could reimburse the government at the military physician’s salary rate. The private sector would likely save on wages, and the Navy would improve its military surgeons’ training and case volume. The military physicians rotating at private hospitals could be recalled in the event of a conflict that requires medical surge elements. The rotations could be conceived of as “deployments” or “shore tours” and assigned for a similar 24-month period. This initiative would produce a more operationally ready military medical force that is more cost-effective for both the Navy and the private sector.

The shortage of physicians in civilian medicine in the United States is projected to grow in the next ten years. Thus, there is no reason Navy surgeons or other military medical professionals should have to watch their skills atrophy when they can help meet the needs of civilian hospitals. Furthermore, civilian hospitals derive a key portion of their bottom line from surgery. Those that are struggling could benefit by paying active-duty physician salaries while collecting the typical reimbursement rates from insurance companies. There surely would be some bureaucratic challenges, but it would allow hospitals helping in national defense to improve their bottom lines and remain financially viable.

Even in the pre-COVID-19 period, hospitals were struggling: “In every year since 2011, more hospitals have closed than opened.”5 Rural hospitals are the most frequent victims. Often, they struggle to recruit and retain physicians, and their challenges have only been exacerbated by the pandemic, as many of the elective procedures healthcare systems rely on for profitability have been suspended.

The impetus to form civilian-military medical partnerships, beginning in surgery and expanding to other fields of medicine, is clear. The lack of training available to military surgeons causes their skills to atrophy, like pilots who never fly their aircraft. The same skills that are fading away are critical to the readiness of Navy Medicine in an era of near-peer competition, where innovation in combat medicine and care modalities will be required to solve a vast array of new medical problems. If the Navy and its medical sector pride themselves on good leadership and sustained excellence, then they have a responsibility to help their talented surgeons preserve their skills.

1. Steve Sternberg, “Top Army Surgeon Blasts Military’s Capability to Handle War Traumas,” U.S. News, 28 October 2019.

2. Lindsay Huth and Steve Sternberg, “Safety in Numbers: Low Volumes at Military Hospitals Imperil Patients,” U.S. News, 19 April 2018.

3. Huth and Sternberg, “Safety in Numbers.”

4. Austin Frakt, “The Rural Hospital Problem,” JAMA Health Forum, 1 May 2019.

5. Frakt, “The Rural Hospital Problem.”